There are two versions of how the plot to murder George Washington first came to light in June 1776, precisely at the moment a large British invasion fleet was descending on New York harbor. In one, as fellow soldiers restrained him, private Thomas Hickey was forced to watch as suspected poisonous peas destined for his commander’s table “were given to some hens … when they immediately sickened and died.”[1] At that, his stomach must have turned for their deaths assuredly sealed his fate had he confessed his own involvement. In the second scenario, Hickey and another soldier, both held in custody for passing counterfeit currency, were overheard making incriminating statements indicating that something untoward was about to descend on the rebel cause. Exposed at one of the most critical moments in the nation’s early history, Hickey soon paid dearly for his actions, becoming the first member of the American military ever executed for treasonous conduct.

As authorities vigorously sought to understand what was happening, evidence revealed a breathtaking scheme of unimaginable dimension that would have brought the Revolution to a sudden end. It was such a devastating plan that it left future Massachusetts governor and veteran Bunker Hill army surgeon William Eustis stuttering in amazed disbelief, calling it “the greatest and vilest attempt ever made against our country; I mean the plot, the infernal plot which has been contrived by our enemies….” Others were similarly confounded: “there has been a most hellish conspiracy at New York,” “a most diabolical plot,” “propitious Heaven hath revealed a most hellish plot,” “a horrid, infernal plot,” “a barbarous and infernal plot” they said.[2]

The conspirators’ goal was ambitious, to say the least. It was also highly secretive as circumspect members working together employed “schemes to distinguish who were in the plot, without speaking.” The commander-in-chief was the primary target, destined to be poisoned, or stabbed, by trusted members of his personal bodyguard: “General Washington was among the first that were to be sacrificed.” It was such an astounding prospect that Eustis, seeking to find appropriate expression, coined a new word to convey the magnitude of what was planned, calling the assassination a “sacricide,” (from the Latin sacer and ædo) or “slaughter of the good.” Then, as the plan unfolded, “every General Officer [including next-in-command General Israel Putnam] and every other who was active in serving his country in the field was to have been assassinated.” Participants further planned to set the city alight in nine different places, destroy large quantities of powder stored in area magazines, spike cannon (rendering them useless by jamming spikes in their touchholes), destroy King’s Bridge to disrupt the Boston Post Road connecting Manhattan northwards to prohibit aid from responding, then “hold possession of the Forts on Powles [Paulus] Hook” awaiting the arrival of the British, those “hungry ministerial myrmidons.”[3]

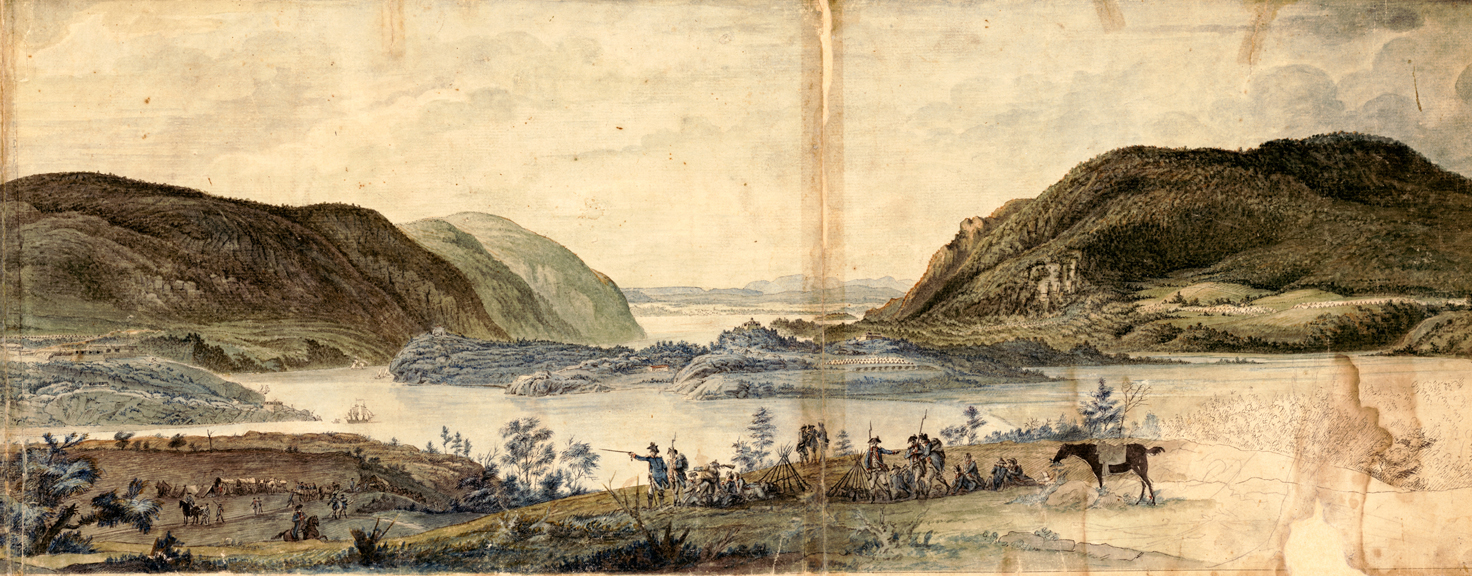

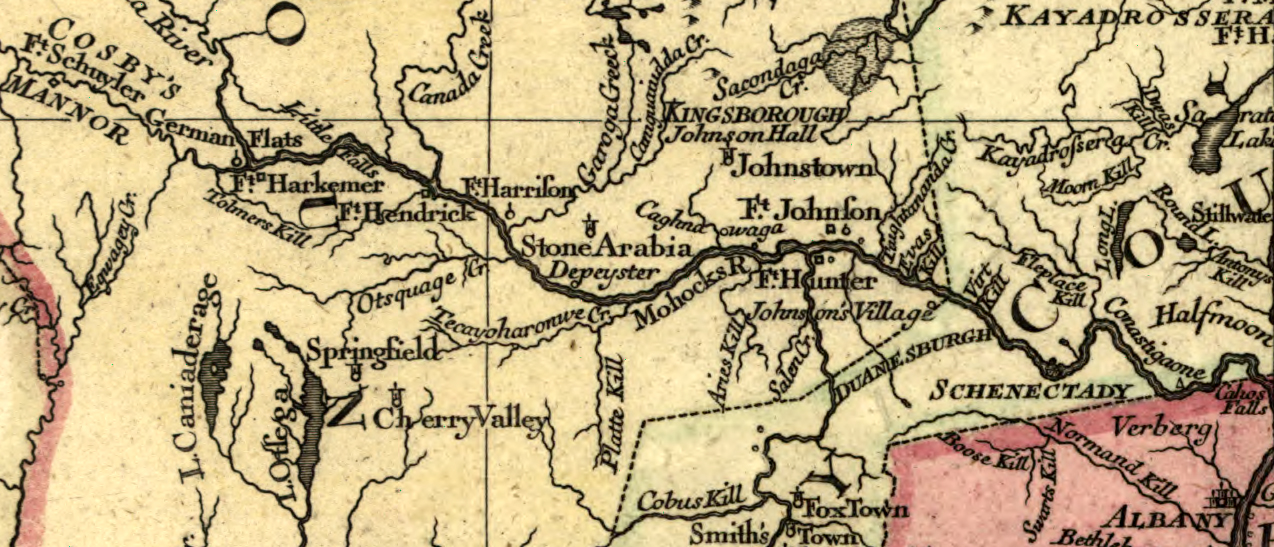

For so much effort to take place over as large an area as New York Harbor, Manhattan, Long Island, Staten Island and nearby New Jersey, as rebel and royal forces converged, required the prestige and resources of someone able to inspire, mobilize and coordinate loyalist support. Royal governor William Tryon (1729-1788) was precisely that person and, while physically isolated in the harbor aboard the 74-gun ship HMS Duchess-of-Gordon, he was hardly out of touch with those many like-minded individuals rallying to their king. Unhindered in his work by an ineffectual rebel presence, a continual flow of boats bearing sympathizers traveled daily to the ship to meet and plan with their defacto leader.

Only three days following his arrival in New York after relocating from Boston, Washington was dismayed to witness loyalists blatantly continuing to communicate with Tryon. On April 17 he dashed off a letter to the local Committee of Safety admonishing them to “prevent any future correspondence with the Enemy” and “to bring condign punishment such Persons as may be hardy and wicked enough to carry it on.”[4] Despite the committee’s promise to do more, two months later little had changed and Washington repeated his concerns, this time to Congress, explaining “The encouragements given by Governour Tryon to the disaffected, which are circulated no one can tell how; the movements of this kind of people, which are more easy to perceive than describe.”[5]

Before the British actually arrived in force in loyalist hotbed New York, reports of conspiratorial plots abounded; as General Charles Lee surmised in March, there was no question but that something was afoot, that “the friends to liberty are to a man convinced, that the tories will take up arms, when encouraged by the appearance of any royal troops.”[6] In preparing the countryside for that eventuality, King’s District (Colombia County) Committee of Safety and Protection reported to Washington on May 13 that they had uncovered “a plot as has seldom appeared in the world since the fall of Adam,” a “most dark and dreadful scheme to overthrow this once happy land” instituted by Tories who “have a set time (when, we cannot find) to rise against the country.” The particulars they feared are not described, but only days later a highly secretive Continental Congress took up the allegations, describing them as a plot “to have massacred the inhabitants who are friends to liberty.”[7] Clearly, there was much for Washington to be concerned with beyond preparing the approaches for the impending Battle of Long Island.

Only a day after the committee’s warning, Washington received a letter from the Committee of Inspection in Fairfield, Connecticut telling him that one of their ships had intercepted “a small sloop in [Long Island] Sound with ten Tories on board, who … confessed they were bound to Long-Island in order to join the Ministerial troops.” Another ten were arrested in Reading, all suspected of being involved in the “horrid plot … to destroy the people of the country, to co-operate with our enemies in every measure to reduce us, and that Long-Island is appointed for headquarters.”[8] Washington wrote back immediately, thanking them for their attention and promised to assist as needed “to root out or secure such abominable pests of society.”[9]

Meanwhile, one of his vigilant waterborne commanders made it a point to closely watch those boarding and leaving British ships and took into custody a “Mrs. Darbage” as she departed one of them. Steadfast in his duty, as he explained to Washington, while “she has absolutely refused to give any account, or answer any questions,” he was not about to be denied in his quest for information, believing that “a little smell of the black-hole will set her tongue at liberty.”[10]

On May 18, an investigating committee in Berkshire County, Massachusetts, revealed yet more of the plot, including that four battalions of loyalists were being raised in New York, as well as hundreds of volunteers flocking to the royal cause in Newton, New Milford and Canaan, Connecticut, to act in concert with arriving king’s troops. One informant inferred that there was even complicit assistance being provided by unnamed individuals in high places, relating that “the plan is so deeply laid in [provincial] Congress and Committees” that they could never be overthrown by the rebels. Addressing the plot with more specificity, yet another related that “he dreamed, at a time not long first there would be a great convulsion in affairs; and in the compass of an hour after it begun things would turn right about, and all the forts would be in possession of the Tories, and the Whigs disarmed and secured.”[11]

As these many reports of extreme plots continued, Washington was summoned to meet with the Continental Congress in Philadelphia. Clearly concerned with having the most up to the minute notification of British arrival, while perhaps conveying his anguish at also being able to quickly cut off loyalist plots, he told second-in-command Israel Putnam to establish a signaling system along Long Island to attend to the works thereon, as well as those at Paulus Hook “which I conceive it to be of importance.” He further instructed that Putnam cooperate with local authorities in their “scheme for seizing the principal Tories and disaffected persons on Long Island, in this City, and the country round about,” doing so in as secret a manner as possible.[12]

Only days later Putnam experienced firsthand the abysmal way that local authorities were handling those loyalists actually taken into custody. On May 30 he complained to the New York Congress that he had personally observed “large companies of gentlemen and ladies visiting the Tories confined in jail … by which means they have an opportunity of knowing everything that passes amongst us .… The bad women confined in jail are constantly visited by men of as bad characters.”[13]

Upon his return to New York, Washington continued his aggressive attempts to cut off any assistance that locals were providing to the enemy and immediately issued orders that eastern Long Island be especially patrolled. There, he instructed Major Peter Schulyer “to prevent, as far as in your power lies, every kind of correspondence and intercourse between the inhabitants and the enemy, seizing upon, and carrying before the Committees of Safety for trial, all those who shall be detected in such infamous practices.”[14]

Washington, now forced to face the new realities before him, acknowledged to the Continental Congress that, due to the inaction or inability of local authorities to stop nefarious communications, “we may therefore have internal as well as external enemies to contend with.”[15] Echoing those concerns, another commander opined, “If the strength of the Whigs be a match for the Tories, and the Army had nothing to fear from or depend upon within, it is as much as we shall ever experience in our favor.”[16]

On the Duchess-of-Gordon Tryon was doing all he could to encourage the rebels’ discomfort, especially from within their own ranks. On June 12, local patriots had struck back at some within the loyalists’ ranks, those unable to avoid detection in the manner that more circumspect plotters instructed: “We had some Grand Toory Rides in this City this week … several of them war handeld verry roughly being carried trugh the streets on rails, there cloaths tore from there becks and there bodies pretty well mingled with the dust.”[17] Those warnings aside, Tryon continued to successfully recruit from the lower classes, as well as at least one member from the elite, none other than David Matthews (c.1739-1800), the mayor of New York City. Unfortunately for Matthews, the Committee of Safety was on to him and on June 21, as the plotters designs were becoming known, it sought and received approval from Washington for his immediate arrest. General Nathanael Greene was then ordered to take him into custody precisely at 1:00 a.m. the following morning, an assignment accomplished by a detachment “who surrounded his house and seized his person precisely” at the assigned time.[18]

As Matthews attempted to extricate himself from suspicions descending on him, he told the Committee on June 23 (a very busy day when some thirty-four were arrested and many interrogations conducted) that he was first approached by Tryon weeks earlier when he had visited him (with Putnam’s permission) on the Duchess. Quite unexpectedly, according to Matthews, Tryon had sought his assistance in paying local gunsmith Gilbert Forbes for bringing guns to the ship. Tryon’s access to money never appears to have been a problem for, in addition to his many other efforts, he was employed an engraver to put into place a counterfeiting operation onboard.[19]

When gunsmith Forbes was interrogated the same day, he admitted he had indeed been assisting Tryon, explaining that he aided in gathering intelligence in preparation for the arrival of the British. Specifically, he said that he had “surveyed the ground and works about [New York City] and on Long Island” and then proposed a plan of attack to Tryon which he accepted. It was a sophisticated operation involving a bombardment by the Duchess, attacks on rebel emplacements, feints, and taking command of several strategic locations including Governor’s Island, the North River, Clarke’s Farm, Enclenbergh Hall, the East River, Jones’s Hill and Bayard’s Hill, before moving on to King’s Bridge.[20]

When gunsmith Forbes was interrogated the same day, he admitted he had indeed been assisting Tryon, explaining that he aided in gathering intelligence in preparation for the arrival of the British. Specifically, he said that he had “surveyed the ground and works about [New York City] and on Long Island” and then proposed a plan of attack to Tryon which he accepted. It was a sophisticated operation involving a bombardment by the Duchess, attacks on rebel emplacements, feints, and taking command of several strategic locations including Governor’s Island, the North River, Clarke’s Farm, Enclenbergh Hall, the East River, Jones’s Hill and Bayard’s Hill, before moving on to King’s Bridge.[20]

Also on June 23, the Committee received a great deal more information from many other individuals describing their knowledge of loyalists’ activities with plots, including two who caused the inquisitors to immediately suspend their hearings. These witnesses, “William Cooper, soldier” and William Savage told of a man named John Clayford who was intimate with a New Jersey woman named Mary Gibbons, also called Judith. Cooper explained in strong terms that Gibbons was the paramour of Washington himself, a fact conveyed to him by Clayford who explained that “General Washington was very fond [of her], that he maintained her genteelly at a house near Mr. Skinner’s … that he came there very often late at night in disguise.”

The witnesses told of conversations they were party to in which Washington’s abduction was discussed and how Judith had agreed to cooperate, an effort the parties determined was too risky. The committee decided to recess for three days to allow them to confer with Washington: “It would be but justice to the General, as he is some way affected by the last witnesses to apprize him of it, and consult with him.” In these next few days there were meetings with Washington, “many other officers … also private examinations of the other prisoners.” As a result, the frenzy increased and many more suspected loyalists were taken into custody: “Their Design was deep, long concerted, and wicked to a great Degree. But happily for us, it has pleased God to discover it to us in season, and I think we are making a right improvement of it (as the good folks say). We are hanging them as fast as we can find them.” And for another relieved at discovering what was afoot, “The plot was a most damnable one & I hope that the Villains may receive a punishment equal to perpetual Itching without the benifit of scratching.”[21]

A week earlier Washington had reportedly learned that the plot against him was about to unfold when a woman approached him, desiring “a private audience. He granted it to her, and she let him know that his life was in danger.” In light of all that was taking place elsewhere, he accorded her such belief that he confided the matter to only a few close friends while waiting for an opportune moment to act. Then, at 2:00 a.m., presumably on June 22, an hour after Nathanael Greene had placed David Matthews under arrest, he pounced, taking only the captain of his bodyguard and “a number of chosen men, with lanterns, and proper instruments to break open houses, and before six o’clock next morning, had forty men under guard at the City Hall,” including “five or six of his own life-guard.”[22]

While the account indicates that those subordinates were arrested at that time, at least two of them, privates Thomas Hickey and Michael Lynch, were already in jail, taken up on June 15 for attempting to pass counterfeit Bills of Credit and then confined “to close custody under the Guards at the City-Hall.”[23] Unable to maintain their silence, Hickey and Lynch confided their activities to fellow prisoner Isaac Ketchum telling him of their involvement with recruiting and paying others to join in supporting the British. Ketchum then reported the incriminating statements to the investigating committee in an effort to free himself from difficulties attending his own counterfeiting operations.[24]

Because of Hickey’s subsequent notoriety, descriptions of his involvement in various plots arose, including trying to poison Washington with tainted peas – which appears impossible because he was in jail at the time.[25] However, what is not in question is that he was closely involved in matters beyond merely passing counterfeit money and which included a female associate (the mysterious Mary “Judith” Gibbons?) who was in close contact with Washington. As one observer described at the time of the arrests, “Yesterday the General’s housekeeper was taken up; it is said she is concerned.” Washington himself proved there was a woman involved; he admonished his troops to rightful conduct following Hickey’s execution, telling them that the best way to avoid such crimes was “to keep out of the temptation of them, and particularly to avoid lewd Women, who, by the dying Confession of this poor Criminal, first led him into practices which ended in an untimely and ignominious Death.”[26]

Thomas Hickey was a member of Washington’s esteemed personal bodyguard, a distinguished company properly known as the “Commander-in-Chief’s Guard.” It was also variously termed “His Exellency’s Guard,” “The General’s Guard,” “Washington’s Life Guard,” and “Washington’s Body Guard,” called into existence only months before in Cambridge, precisely at noon on March 12, 1776, just as the British were preparing to remove themselves from nearby Boston.[27] The day before, recognizing that the times required his relocating and also increased security, Washington ordered commanders of each regiment to provide “a particular number of men as guard for himself and baggage.” Each was requested to send four “good men, such as they can recommend for their sobriety, honesty and good behavior” to headquarters the following day for final selection. He further required that the candidates be between “five feet eight inches to five feet ten inches, handsomely and well made … clean and spruce … perfectly willing [and] desirous of being on this Guard … they should be drilled men.”[28]

To distinguish this highly select group from others, their uniforms consisted of “a blue coat with white facings; white waistcoat and breeches; black stock and black half-gaiters, and a round hat, with blue and white feather.” Additionally, a special flag was created made of white silk bearing an image of a guard member holding a horse while receiving “a flag from genius of Liberty, who is personified as a woman leaning upon the Union shield” and with the corps’ motto “CONQUER OR DIE” emblazoned across the top.[29]

Hickey was described as “a dark-complexioned Irishman,” “five feet six inches high, and well set,” who had deserted from the British army a few years previously. He had been living in Wethersfield, Connecticut, “where [he] bore a good character,” and was one of those selected from the ranks of Knowlton’s Rangers. He was well received by Washington, gaining his confidence and was considered “a favorite.”[30]

However, it was not long before he became disaffected with the rebel cause and solicited the assistance of fellow guard members to undermine it. Perhaps due to the speed with which the overall plot was uncovered, in their haste to put the matter behind them authorities never charged Hickey specifically with any attempted assassination of Washington. Notwithstanding, the general information revealed during the extensive investigation demonstrated that he was a part of a plot with that very end in mind. With his special access and privilege, Hickey was not only to kill Washington, but to aid other guard members with special access to prized weaponry to spike cannon and destroy ammunition magazines.[31]

Hickey’s fate was resolved in lightening fashion on June 26 when he faced a court martial at headquarters, charged with “exciting and joining in a mutiny and sedition, and of treacherously corresponding with, inlisting among, and receiving pay from enemies of the United American Colonies.” The trial was short, requiring the testimony of only four witnesses to establish that Hickey had recruited members of the guard to aid the British and had received money towards that end. When called upon to defend himself, all he could say was that he “engaged in the scheme at first for the sake of cheating the Tories, and getting some money from them” and that he allowed his name to be sent to Tryon so that “if the enemy should arrive and defeat the Army here, and he should be taken prisoner, he might be safe.”[32] None of it proved of any assistance; he was immediately found guilty and sentenced to death.

Two days later, some twenty thousand people turned out to witness Hickey’s hanging. He reportedly issued an ominous warning. After wiping the tears from his face, he was observed to have “assumed [a] confident look,” and then to say “You remember General Greene commands at Long Island [and that] unless General Greene was very cautious, the Design would as yet be executed on him.”[33] That part of the plot, of course, never unfolded. The rebel army turned to face the British arriving in New York harbor during the next few days.

For Washington, Hickey’s betrayal remained an ongoing concern. When he had occasion to reorganize his vaunted Guard the following year, he decided that those of foreign birth could not be included. As he explained to his commanders when he requested potential candidates, “I am satisfied there can be no absolute security for the fidelity of this class of people, but yet I think it most likely to be found in those who have family connections in the country. You will therefore send me none but natives, and men of some property, if you have them.” He further cautioned that “I must insist that, in making this choice, you give no intimation of my preference of natives, as I do not want to create any invidious distinction between them and the foreigners.”[34]

The Commander-in-Chief’s Guard remained in existence until the end of the war, disbanding in 1783, and there are no further reports of the kinds of treasonous conduct that Thomas Hickey was convicted of participating in. The extent of the plot to kill George Washington, or the likelihood of its ultimate success, will probably never be known, but there is no question that he barely escaped with his life at one of the most important moments in the Revolution.

[FEATURED IMAGE AT TOP: Flag of Washington’s Life Guard (plotter Pvt. Thomas Hickey was a member). Source: Benson Lossing, The Pictorial Field-Book of the Revolution. 2 vols. New York: Harper, 1851–52.]

[1] Benson John Lossing, Washington and the American Republic (New York: Virtue and Yorston, 1870), 2:176.

[2] Dr. William Eustis to Dr. David Townsend, June 28, 1776, New England Historical and Genealogical Register (1869), 23:206-09; William Whipple to John Langdon, June 24, 1776, American Archives Series 4, 6:1050; John Rogers to the Maryland Convention, June 25, 1776, American Archives Series 4, 6:1064; Jonathan Trumbull to Philip Schuyler, June 28, 1776, American Archives Series 4, 6:1126; letter to Justices in Massachusetts, American Archives Series 5, 1:210; Extract of a letter, June 24, 1776, American Archives Series 4, 6:1054.

[3] Extract of a Letter from a Gentleman in New York, June 27, 1776, American Archives Series 4, 6:1101; Eustis to Townsend, June 28, 1776; Solomon Drown to Sally Drown, June 24, 1776, Dawson, Henry and Abraham Tomlinson, New York City during the American Revolution (New York, privately printed 1861), 77-78; William Green testimony, Court Martial for the trial of Thomas Hickey and others, American Archives Series 4, 6:1084; Edward Bangs, Journal of Lieutenant Isaac Bangs, April 1 to July 29, 1776 (Cambridge: J. Wilson and Son, 1890), 48; Constitutional Gazette (New York City), June 29, 1776.

[4] Washington to the Committee of Safety of New York, April 17, 1776, Letterbook 1, George Washington Papers at the Library of Congress, 1741-1799, 187 (http://memory.loc.gov/mss/mgw/mgw3c/001/190187.jpg, accessed June 11, 2014).

[5] Washington to the President of Congress, June 10, 1776, American Archives Series 4, 6:789.

[6] Charles Lee to John Hancock, March 5, 1776, Life and Memoirs of the Late Major General Lee (New York: Richard Scott, 1813), 289.

[7] Matthew Adgate to Washington, May 13, 1776, American Archives Series 4, 6:438; On the Report of Mr. Morris, May 19, 1776, American Archives Series 4, 6:1318.

[8] Jonathan Sturges to General Washington, American Archives Series 4, 6:455.

[9] Washington to Sturges, May 16, 1776, American Archives Series 4, 6:477.

[10] Letter from Colonel Tupper to General Washington, May 16, 1776, American Archives Series 4, 6:476.

[11] Information on oath before eleven Committees, American Archives Series 4, 6:504.

[12] Instructions to General Putnam, May 21, 1776, American Archives Series 4, 6:534-35.

[13] Letter from General Putnam to the New York Congress, May 30, 1776, American Archives Series 4, 6:626.

[14] Orders of General Washington to Major Schulyer, June 10, 17776, American Archives Series 4, 6:792.

[15] Washington to the President of Congress, June 10, 1776, American Archives Series 4, 6:789.

[16] Colonel Huntington to Govenor Trumbull, June 6, 1776, American Archives Series 4, 6:725.

[17] Peter Elting to Capt. Richard Varick, June 13, 1776, Dawson, New York City during the American Revolution, 97.

[18] Return by General Greene of the arrest of Mr. Matthews, June 22, 1776, American Archives Series 4, 6:1158.

[19] Examination of David Matthews, the Mayor of New-York, June 23, 1776, American Archives Series 4, 6:1164; Deposition of Irael Youngs, June 26, 1776, American Archives Series 4, 6:1177.

[20] Examination of Gilbert Forbes, June 23, 1776, American Archives Series 4, 6:1178.

[21] Minutes of a conspiracy against the liberties of America (Philadelphia: John Campbell, 1865), 22-23; Eustis to Townsend, June 28, 1776, New England Historical and Genealogical Register, 23:208; Peter Curtenius to Richard Varick, June 22, 1776, Dawson, New York City during the American Revolution, 68-69.

[22] Dawson, New York City during the American Revolution, xii-xiii.

[23] Michael Lynch and Thomas Hickey committed to prison, June 15, 1776, American Archives Series 4, 6:1406.

[24] Isaac Ketcham requests to be heard before the Congress, June 17, 1776, American Archives Series 4, 6:1410.

[25] Lossing, Washington and the American Republic, 176.

[26] Extracts of Letters from New-York, American Archives Series 4, 6:1054; General Orders, from June 28 to June 30, 1776, American Archives Series 4, 6:1148.

[27] On April 15, 1777, an clearly exasperated Continental Congress resolved, “That the appellations, ‘Congress’s own regiment,’ ‘General Washington’s life guards,’ & c. given to some of them are improper, and ought not to be kept up; and the officers of the said batallions are required to take notice hereof, and conform themselves accordingly.” Journals of the Continental Congress, 7:270.

[28] Carlos Emmor Godfrey, The Commander-in-Chief’s Guard, Revolutionary War (Washington, D.C.: Stevenson-Smith Company, 1904) 13, 19-20.

[29] Lossing, Washington and the American Republic, 177-78.

[30] Lossing, Washington and the American Republic, 176; Minutes of a Conspiracy Against the Liberties of America, ix.

[31] Eustis to Townsend, June 28, 1776, New England Historical and Genealogical Register, 23:208.

[32] Court Martial for the trial of Thomas Hickey and others, June 26, 1776, American Archives Series 4, 6:1084

[33] Eustis to Townsend, June 28, 1776, New England Historical and Genealogical Register, 23:208.

[34] Godfrey, The Commander-in-Chief’s Guard, 42.

9 Comments

Very interesting and informative article. I wonder if Hickey’s dying declaration about Greene may have been true but unsuccessful. Greene became quite ill before the Battle of Long Island. Could it have been an assassination attempt with poison that failed?

SPM,

You raise a very interesting question and one I do not have an answer for.

In his Life of Nathanael Greene, Major-General in the Army of the Revolution (published 1846), George W. Greene reports that Greene was suffering from “bilious fever, which brought him to the brink of the grave. It was towards the middle of August, the most dangerous season” leaving him bedridden during the battle (p. 39). While Hickey was executed in June, it may be possible that someone else involved in the plot was able to get to Greene and provide him with a poison of some kind. Just conjecture, but it adds an interesting twist to his physical problems.

The other issue that has been raised in the literature (word count did not allow for a full discussion of this or the report of Washington’s intimate relationship with Mary Gibbons – that is something worth pursuing!), is that Hickey was referring to a co-conspirator named Green. Perhaps he was warning this other Green to be careful in what he was doing; again, just conjecture.

Thanks for bringing this up.

Thank you for this very interesting article. I was vaguely aware that there had been a problem with the Life Guard early on but nothing as serious and extensive as this! Also I did not realize that Washington may have had secret liaisons with other women! May be I should not be surprised as he did enjoy the company of females when possible during the long war. The dance balls in Morristown, NJ and officer wives presence at Valley Forge come to mind (even though Martha was often present).

Both issues are fascinating in their own right.

Thank you again for a great read!

John Pearson

John,

I am glad that you enjoyed this story. It is interesting to see Washington transitioning from wanting fine, upstanding men on his Guard without qualification as to origin of birth, to wanting fine, upstanding “natives” when he specifically rejected considering any further use of “foreigners.” Who could blame him when the evidence revealed that employing disenchanted deserters from the British army (there was at least one other Irishman in addition to Thomas Hickey) resulted in their turning and thinking about sinking a knife into his chest or serving him poisoned peas.

The issue of Washington’s involvement with another woman is also interesting. Nineteenth century writers (apologists?) have tried to downplay allegations of any dalliances of the forty-four year old commander-in-chief, but I find the references to his having done so as not being quite fully discredited. Thank you for your interest in this fascinating moment in George Washington’s life.

Gary

Gary – very nice article!

I was somewhat familiar with the plot against Washington being connected to members of his initial Life Guard, but not to any detail as you have presented here. The only reason I was aware at all of the plot is because I am a direct lineal descendent of Sergeant William Pace of Virginia, who was selected as a member of Washington’s reconstituted Life Guard in May, 1777. Sgt. Pace served with Washington throughout the rest of the Revolutionary War and remained in the Life Guard until the unit was disbanded in November, 1783.

Though the reconstituted Life Guard apparently never suffered any more murderous assassins and traitors, I wonder how many subsequent attempts were made by outside plotters, civilian or military, to assassinate General Washington. Taking Washington out of action before Yorktown would have constituted a severe blow to the Revolution. Are there any publications you know of that address the subject? Is that a subject you are currently researching?

It is amazing to me how little the average American citizen knows of the life and times of our nation’s first Commander in Chief and the “Father of our nation”, beyond the simplistic one-dimensional stories taught (or at least, as they used to be taught) to American schoolchildren.

Duane,

Thank you for your kind words. I cannot put my finger on the specific references, but do recall reading in the not too distant past that the British had refused to engage in a policy that involved assassination attempts, perhaps on the basis that what goes around, comes around. That is not to say that an industrious, ambitious pocket of loyalist supporters might not take it upon themselves to strike out if they saw an opportunity. I am not aware of Washington’s policy in that regard, but it is interesting that he fully intended to kidnap Arnold following his treachery.

To answer your question, yes, I had thought about additional research into this, but other projects are calling too loudly at the moment to allow that to happen. So please feel free to take it up and pursue as your interests direct.

I further agree with your observation regarding the one-dimensional viewpoints that are being inflicted on an unsuspecting populace. It is a most worthy goal that JAR and its contributors seek to rectify.

By the way, as noted in footnote 27, the Continental Congress was pretty upset with everybody calling the Commander-in-Chief’s Guard anything other than that. So, as attractive and appealing as “Life Guards” might sound, that would pretty much tick off a congressman of the times!

Not sure if this comment will reach anyone here four years later. I am using this article for research and am hoping someone might clear something up for me. Hickey was supposedly chosen from Knowlton’s Rangers, the citation of which comes from Lossing’s “Washington…” I downloaded a copy, and it seems that Lossing himself did not leave a citation for this (or any) facts. Why this strikes me is because Knowlton was not ordered to form the ranger unit until he was promoted to Lieut. Col. on August 12th that year, some six weeks after Hickey’s death. Supposing Lossing had a good reason for stating what he did, what reason might that be? Did Knowlton himself recommend Hickey out of his same regiment? Was Knowlton already training and forming an elite unit prior to Washington’s orders? I have been on Knowlton’s trail for about a year, and would appreciate any information readers might have. Wonderful article that is of great help to me!

Hi Ethan,

Happy to help you…four years later wasn’t an issue after all! I gave a talk on Knowtlon’s Rangers as part of my presentation to the FBI’s New York Office several years ago. Knowlton was from Ashford, CT and Hickey was not. Hickey was also not from anywhere near Ashford. According to Rev. War muster rolls, before Knowlton was commander of his Rangers beginning August 12th, there were no Ranger units, nor was he running another proto-Ranger unit, though that was a good theory of yours. He was a major in a very interesting regiment: the 20th Continental. That doesn’t seem interesting until you read the list of who were the senior officers: Major and then Lt. Col. Knowlton (he was promoted on August 12th when he created his Ranger unit), and John Durkee of Norwich as colonel and and commander. Who had Durkee replaced around August 12th? None other than Colonel Benedict Arnold, also of Norwich.