A recent home improvement project led to the Home Depot located at 2324 Elson Green Avenue, Virginia Beach, Virginia. The area is in the middle of the expansion of the old narrow two-lane country Princess Anne Road, into a modern six lane highway with access lanes needed to support the growing private and commercial vehicle traffic as the City of Virginia Beach expands south into the once rural farmlands of Princesses Anne County. For a brief moment my mind quickly flashed back to February 15, 1781 and what the area may have looked like on that day. Morning dawned that day in Virginia with Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene’s army safely across the Dan River. After a two-week pursuit across the rain-filled rivers of North Carolina, relentlessly hounded by Lt. Gen. Lord Cornwallis’s army, Greene’s forces could now rest with the swollen Dan River between his forces and those of Cornwallis. With extended lines of operation and short of supplies, Cornwallis consolidated his territorial gains in North Carolina and contemplated his next move. Greene found himself in Virginia, the Whig’s breadbasket of the revolution, with interior lines and access to supplies and manpower.[2] Yet Virginia was far from the secure base of operations the Whigs or Patriots needed to rebuild their Southern Army. As British strategy focused southward the revolution was entering a new phase. Virginia was now open to direct attack from both land and sea; Virginia’s role in the American Revolution now involved direct combat on Virginia soil.

In the Tidewater Region of Virginia, just 160 miles due east of Greene’s position another little-known engagement unfolded at James’s Plantation, in the area of what is today the Home Depot parking lot and adjoining businesses, as British forces executed a hasty attack on Patriot militia. Brig. Gen. Benedict Arnold, now a British officer after his defection from the revolutionary cause the previous October, executed his own campaign against local Whig militia units in an attempt to reestablish British authority in Virginia. Arnold wanted to build on the military success he achieved during his raid on Richmond the previous month to secure his main operating base in Portsmouth, on the Elizabeth River, from attack.[3] Apparently, Arnold believed his stature as an effective leader and battlefield commander would awe the local population and result in shifting their allegiance to the Loyalist cause.[4] From his base in Portsmouth, Arnold ordered two of his most able commanders, Lt. Col. John Graves Simcoe and Capt. Johann Ewald to move into Princess Anne County in pursuit of Whig militia, reportedly operating there.[5] While Lord Cornwallis would experience no victories on February 15, 1781, after a difficult two-week campaign, Arnold and his subordinates would again take center stage and build on his previous military success. Coastal Virginia was about to become the major military theater of the American Revolution and one of the opening salvos unfolded this day with the skirmish at James’s Plantation. The outcome of this skirmish may have provided Arnold with valuable insight on the viability and sustainability of his defection and the passion of the local Patriot militia to the ideals of the revolution. Today, in retrospect, Arnold’s military competence and that of his trusted subordinates could not overcome the Whig authority in the region or the fervor of the Patriot cause to crush revolutionary movement in Tidewater Virginia. Perhaps the events of February 1781 in Princess Anne County led directly to breaking Arnold’s belief that he could convert Patriot militia to become Loyalists by defeating them in battle and offering them support to return their loyalties to the crown.[6]

Lt. Gen. Sir Henry Clinton, the British commander-in chief of the King’s Forces in North America, appointed Arnold a Brig. Gen. in the British Army after his defection to the British while attempting to deliver West Point, a key fortification in the Hudson River Valley. Finding himself with an aggressive general and a limited offensive force list,[7] Clinton decided to send Arnold on a mission to Virginia to continue the work started there by Maj. Gen. Alexander Leslie.[8] Leslie, after only a month in Virginia in the fall of 1780, promptly obeyed Cornwallis’s orders to move by sea from Virginia to the Carolinas to reinforce Cornwallis for his winter campaign against Greene. This left Virginia once again firmly in control of the Whig government. Clinton countered sending Arnold, with a small but resilient combat-capable force made up of a mix of regular and Loyalist troops. These included:

An important element not included in the above totals were the German auxiliary forces, specifically those under the command of Capt. Johann Ewald. Ewald lists German units including: elements of the Hessian and Anspach foot jagers, two battalions of Hessian grenadiers, the Anspach Brigade, and the Althouse sharpshooters,[10] a total of 450 men, bringing Arnold’s total forces to approximately 2,200.[11]

Arnold had a three-fold mission: attack any of the Continental Army magazines and supply depots (“provided it may be done without much risk”), “establish a post at Portsmouth on Elizabeth River,” and “distribute the proclamations you take with you (which are to be addressed to the inhabitants of Princess Anne and Norfolk Counties).”[12] Clinton’s focus on Princess Anne and Norfolk counties was to add to the defensibility of Portsmouth in securing the eastern flank and the primary approach from North Carolina (via the Great Bridge). The intent was to recruit Loyalists from those counties to secure the area and approaches from that region. The Dismal Swamp would protect the south; the navy would protect the Elizabeth River and Hampton Roads leaving only the western flank toward Suffolk the open flank needing attention. At the time, the British assessed the greatest threat to Arnold’s mission as the militia units assembled near Suffolk “with Two thousand five hundred, or three thousand men.”[13] To counter this threat, Arnold proposed a scheme to interdict the flow of militia from the south and west. This involved securing the Currituck Sound of North Carolina to support the British operations leading to control of the rivers reaching into Norfolk and Princess Anne Counties from North Carolina. This would limit militia movements from the south, isolating Norfolk and Princess Anne Counties furthering British control of the region.[14] Arnold took pause of this plan when three French vessels arrived in Lynnhaven Bay. However, when this threat proved short-lived, he refocused his efforts.[15] The most immediate and significant impediment to Arnold’s operations were small bands of local Whig or Patriot militia moving relatively freely throughout the region. These groups of militias threatened not only the post at Portsmouth but also the larger goal of recruiting Loyalists and building Loyalist militias in Norfolk and Princess Anne Counties.[16]

Local Patriot units from both Virginia and North Carolina made it difficult for Arnold to recruit and even to forage and supply the 2,200 troops at the post at Portsmouth. Arnold was aware of several different plans to attempt to capture and hang him.[17] Arnold, always an offensive-minded commander, saw his best option as applying pressure against Whig militia to keep them off-balance. Loyalists in Norfolk and Princess Anne Counties experienced regular harassment from Patriot militia units, tempering the local support that Arnold needed to carry out his mission to build Loyalist support and recruit and build Loyalist militias.[18]

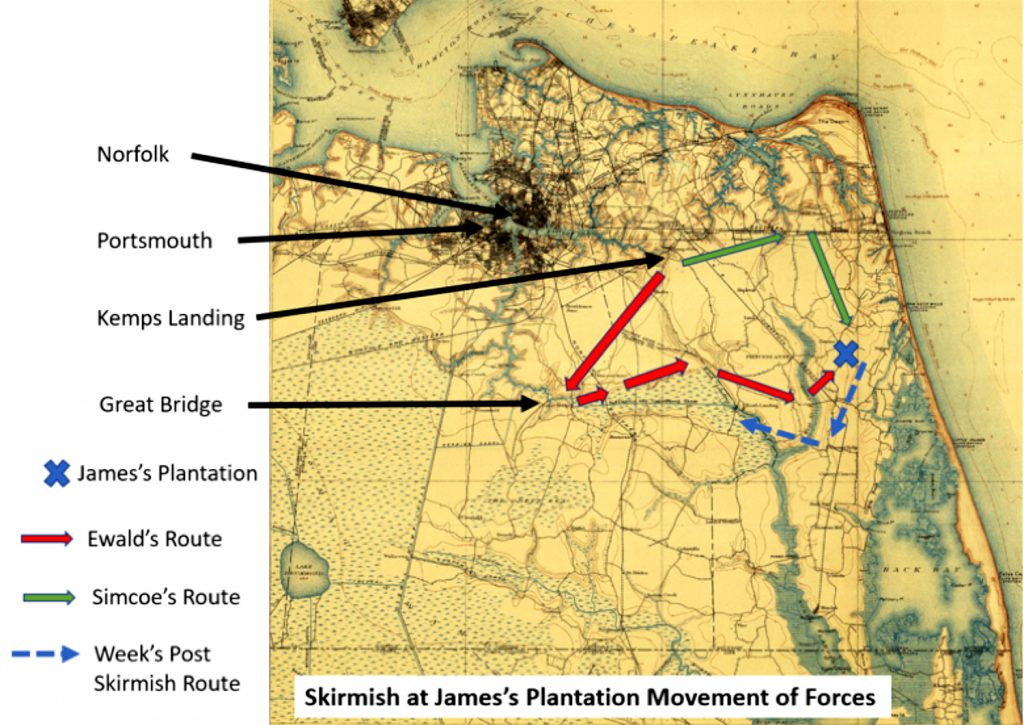

One of the local militia commanders involved in the activities against Arnold was Capt. Amos Weeks. Weeks was considered a competent partisan commander and worthy adversary by his opponents.[19] Weeks remains an elusive figure in the history of the revolution, however he was very active during the war and recent research, by Bell and Cecere, suggests he led militia units as early as 1775 and perhaps commanded a privateer before returning to lead Princess Anne County Militia.[20] One of the few surviving genealogical records documenting Weeks’s connection with Princess Anne County is his marriage to Elizabeth Keeling, a local resident, in 1779.[21] Both Simcoe and Ewald report he followed the British to Yorktown and operated near Gloucester in August 1781, so his efforts included operations north and south of the James River.[22] Arnold found Weeks’s activities such a threat that Arnold ordered a force of the Queen’s Rangers under Lt. Col. John Graves Simcoe and a task organized unit led by Hessian Jagers under Capt. Johann Ewald to capture Weeks and destroy his forces.[23] Simcoe and Ewald designed an operation involving a classic double envelopment, as depicted on Map 1, to trap Week’s militia between the two converging forces and capture, kill or disperse the Whig militia, mitigating this threat.

Kemp’s Landing, a small but important settlement at the head of the Eastern Branch of the Elisabeth River served as the starting point of the operation. Kemp’s Landing and was also the site of successful British military actions in 1775, then under the command of John Murray, Lord Dunmore, the Royal Governor of Virginia.[24] Here on February 13, 1781, Simcoe and Ewald split with Simcoe heading nearly due east to London Bridge and Ewald heading south to the Great Bridge.[25] While Simcoe drew the attention of Weeks, Ewald would move in from the south and west in an attempt to envelop the militia. Those with knowledge of the terrain in Norfolk and Princess Anne Counties, the modern cities of Norfolk, Virginia Beach and Chesapeake, would quickly understand water impedes one’s movements at every location. Canals and drainage ditches bisect the area today, but in 1781, the area was a series of broad swamps with an occasional strip of reasonably dry terrain, normally about ten feet above seal level forming the high ground. During the rainy season, December through March, the low ground was next to impassable. A few key choke points dominated the landscape when one attempted to traverse the low ground. Controlling the high ground and few bridges allowed for freedom of movement.

Ewald conducted an uneventful movement to Great Bridge, at the head of the Southern Branch of the Elizabeth River, following the high ground today traversed by Kempsville Road. Great Bridge was the sight of the British bloodbath on December 9, 1775, ceding control of Virginia to the Whigs. Now, Ewald and Simcoe were confronted with trying to wrestle control of the population from the Whig government. After resting for the evening, Ewald, on February 14, 1781 proceeded to cross one of the many drainage basins of the region a marsh and swamp he called the Devil’s Elbow Swamp, today dammed to form Stumpy Lake, one of the many tributaries of the North Landing River. He likely followed the trace of what is today Elbow Road, arriving on the east side of the swamp, near modern-day Salem Road, in the City of Virginia Beach. There a messenger from Kemp’s Landing provided updated intelligence on the Whig militia movements and location. The report placed the Whig militia near Dauge’s Bridge that spanned the modern West Neck Creek[26]—just six miles away and clearly withing Ewald’s striking distance, despite the just completed and physically demanding movement through Devil’s Elbow Swamp, with daily temperatures in the forty-degree Fahrenheit range.

After resting his exhausted troops, on February 15, 1781, Ewald moved his small but capable force southeast following the trace of the modern North Landing Road. With the help of a local loyalist guide, Ewald found a route through the swamp, at one-point water reached the saddles of his horses, indicating another wet, cold and physically demanding movement. During this movement Ewald split his force with his infantry crossing in one location and his cavalry in another. Reassembling his forces on the dry ground of Pungo Ridge, now on the east side of West Neck Swamp and West Neck Creek, Ewald needed fresh intelligence.[27]

Shortly after emerging from the swamp, Ewald’s force surrounded a house and forced the occupant to reveal what he knew about the movement of Patriot militia. He learned that Weeks had burned Dauge’s Bridge to prevent use by the British.[28] Week’s location was presumably at Jamison’s Plantation—near the current intersection of Oceana Blvd. and General Booth Blvd., east of modern Naval Air Station Oceana, Virginia Beach. However, first intelligence reports are always questionable, there was apparently confusion as to the exact location of the Whigs. It was not long before Ewald realized that Weeks and the militia were much closer, south of Jamison’s Plantation—at James’s Plantation near the intersection of modern Princess Anne Road and Elson Green Road.[29]

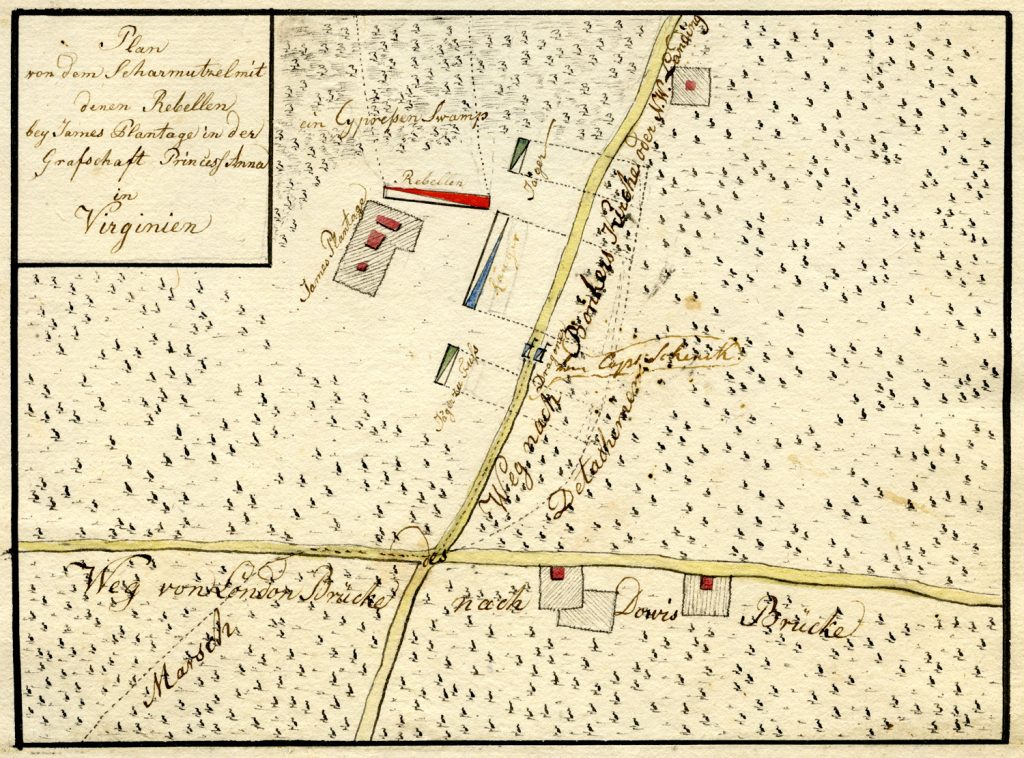

Once Ewald realized that Weeks and his militia were close by, he quickly devised a plan to surprise the unsuspecting Whig militia. The cavalry under Capt. Shank took to the road to act as a diversion. Meanwhile, Ewald and the 180 jagers and rangers moved under the cover of the woods along the south side of modern Nimmo Methodist Church and south of Princess Anne Road. As Ewald approached, undetected through the woods, he observed the Whig militia firing at Shank and the cavalry. As planned, and with their attention fixed on the on the cavalry unit to their front, Ewald moved out of the woods, over a fence surrounding the plantation and opened fire on the left or southern flank of the Whig militia.[30] Ewald’s rendering of the action is provided as Map 2.

Confusion reigned when the Whig militia realized they were under attack in their flank, they responded by retreating into the swamp to their rear or the east. At this point the militia could not disappear into the swamp quickly enough, as they scattered the cavalry and jagers under Lt. Bickell managed to cut down or bayonet some sixty men. Ewald’s force of about 200 soldiers managed to capture another fifty militia before the stunned men could escape. Ewald sent a messenger to inform to Simcoe at London Bridge about the engagement and asked Simcoe to join them at James’s Plantation.[31] However, Ewald would later concede none of the men he captured would join the Loyalist cause.[32]

After enjoying the bounty offered at James’s Plantation, the combined British force of Hessians and Queen’s Rangers headed south toward Pungo Chapel on February 16, 1781. Interrogating a captured militiaman, the British learned of a predesignated Whig militia rendezvous point near the Northwest Landing. Setting an ambush just four miles south of James’s Plantation at Pungo Chapel,[33] a way-point the militia used when moving to Northwest Landing, the British captured additional militia and the elusive Capt. Weeks narrowly avoided captured himself.[34] After unsuccessfully searching the high ground used for farming known as Pungo Ridge, along modern-day Princess Anne Road for more stragglers, the forces returned north. They traveled through what is now Naval Air Station Oceana, passing the Ackiss Plantation and spent the evening at the Cornick Plantation not far from London Bridge, Simcoe’s previous blocking position.

On February 17, 1781 the force finally returned to Portsmouth via London Bridge, Kemp’s Landing, and Norfolk.[35] After the skirmish, Benedict Arnold hosted a gathering in Kemp’s Landing, probably at Pleasant Hall, a grand brick plantation home that remains standing today, to garner the loyalty of the inhabitants by administering another oath, similar to what Dunmore had six years earlier.[36] Arnold even posted what amounted to a “bounty” on Amos Weeks in an effort to prevent Whig militia opposition.[37] Unable to recruit for his “American Legion,” Arnold and the British forces primarily confined themselves to the post at Portsmouth, the growing pressure from Virginia and North Carolina Militia units and now regular Continental Army units under Baron von Steuben made venturing outside their defenses risky.[38] Arnold grew increasingly cautious and reportedly carried with him two small pistols, preferring a self-inflicted demise rather than capture.[39]

The actions of Ewald’s Hessians and Simcoe’s Queen’s Rangers in Princess Anne County, to include the skirmish with the Princess Anne Militia at James’s Plantation, were part of the overall plan to eliminate the Patriot operations and opposition in Princess Anne and Norfolk Counties in order to generate the Loyalist support and recruit into Arnold’s “American Legion.” However, these operations highlight the complexities of partisan warfare and were not without a cost. In one Militia attack on the British post, Ewald was wounded—shot in the knee. Amos Weeks may have been part of this attack. While Ewald was recovering from his injury at a British hospital in Norfolk, Weeks continued to torment him. Ewald received word from Weeks that “he hoped to square accounts with me again in Norfolk.” Weeks also offered to burn the hospital with Ewald inside.[40] The origin of the animosity between these two is unknown but may simply be the natural tension associated with partisan or irregular warfare.

Surprisingly, the Skirmish at James’s Plantation actually appeared in an eighteenth-century manual of partisan warfare. The work, Treatise on Partisan Warfare, by Johann Ewald himself, references his clash with Amos Weeks’ militia and their subsequent escape through the swamps of Virginia and North Carolina. Because Ewald did not specifically mention James’s plantation in his guidelines on “How to Act Upon a March” the event would remain anonymous for many more decades. As Ewald described the event:

If there is certain knowledge of the area where the enemy detachment to be beaten stays, a different disposition can be made. The corps or detachment is divided into two, maybe three groups, each of which is instructed as to where to retreat to in case it is attacked by the enemy. However, the location of each of them has to be such as to allow the easy support of it by the other two if it should be attacked, or so that the group attacked can lure the enemy to the vicinity where the other groups are, which will bring the enemy into a crossfire where it will certainly be defeated. If time and area permit an attack on the enemy from more than one side, this opportunity must never be lost sight of. Thus during the Virginia campaign Colonel Simcoe was sent by General [Benedict] Arnold from Portsmouth across the Elizabeth River into Princess Anne County to search for and destroy an enemy detachment which had badly mistreated the royalist subjects. It also often interfered with the foraging of Arnolds corps and made communications on land and water between Portsmouth and the great bridge very unsafe. The colonel took his way across Kemp’s Landing and the London Bridge while I was sent with another detachment on Simcoe’s right toward the great bridge. From this post I turned left and passed Dauge’s and Brock’s swamps, which were considered impassable by the enemy, especially for cavalry, in order to cut off the retreat of the enemy toward Northwest Landing or in the direction of North Carolina. Both parties met the enemy detachment at two different times, through which it was completely cut to pieces, and what was left retreated through pathless swamps toward North Carolina.[41]

Thus, centuries before the modern inhabitants of Princess Anne County learned the details of the Skirmish at James’s Plantation, Prussian military strategists such as Carl von Clausewitz and Gerhard von Scharnhorst were recommending Ewald’s work, with the James’s Plantation vignette above, to their students.[42]

While the primary sources on the Skirmish at James’s Plantation came from the British perspectives, via the journals of Ewald and Simcoe, several Revolutionary War pension applications allude to the event. While not naming James’s Plantation as the location, the timeframes and other identifications (names and geographic locations) provide additional support of the event and give a clear picture of the nature of partisan warfare in the area. John Brown stated that he “joined Capt Amos Weeks company . . . and while in Princess Ann his duty was to watch the motions of the enemy, prevent his plundering the inhabitants and his carrying off Slaves.”[43] William Bryan stated “During this tour he was engaged in a considerable skirmish with a party of the enemy who made a sally from the fort and was engaged in another skirmish in Princess Anne County.”[44] William Hill was awarded a pension for “loss of his right arm whilst serving as a volunteer in a corps commanded by Captain Amos Weeks from the county of Princess Anne.”[45] Thomas Bonney also reported a “a skirmish with the enemy at Juniper swamp.”[46] There were several areas near James’s Plantation that were sometimes referred to as the Juniper Swamp but this documentation further supports the Whig militia operations in the vicinity of James’s Plantation.

After James’s Plantation the local militia continued to harass Arnold’s force and make foraging dangerous. However, the British gained significantly more flexibility in engaging the militia offensively after the arrival of Maj. Gen. Philips and his reinforcements in late March doubling the size of the force in Virginia adding 2,200 men and superseding Arnold in command.[47] The efforts of the local militia were significant and had an impact on British activity in the area by preventing Benedict Arnold from achieving his objectives in Virginia. The larger issue may be the enduring impact of these events on Benedict Arnold.

By failing to capture Amos Weeks, an effective partisan leader regularly mentioned by both Ewald and Simcoe, Arnold was unable to provide a secure base of operations in Portsmouth. With the arrival of Maj. Gen. Philips and Later Lt. Gen. Lord Cornwallis the Southern Campaign enter a new phase in Virginia. Perhaps the events in Norfolk and Princess Anne Counties and specifically the action at James’s Plantation had a convincing impact on Benedict Arnold. Martin and Lender find Arnold’s Virginia Campaign served as an education for him. The failure of Arnold to convert any of the men captured at James’s Plantation to the Loyalist cause supports the findings of Lender and Martin. Their assessment of Arnold finds his efforts to influence the population to “reconcile their differences with the king,” was largely a “pipedream.” Arnold’s inability to turn the population in Norfolk and Princess Anne Counties against the Whig government and the passion the Patriot militia showed for their cause likely convinced Arnold that restraint in dealing hisfellow American was a lost cause. Future actions against his countrymen would reveal his frustrations with restraint when he next resorted to destruction.[48] However, prudent commanders engaged in a campaign for the hearts and minds of the population must show restraint. It is also interesting to note that “restraint” is one of the twelve contemporary principles of joint military operations practiced by the Armed Forces of the United States.[49] However, when conventional forces engage in partisan or irregular warfare, restraint is a necessary but difficult principle to apply, Benedict Arnold learned this lesson in Virginia. James’s Plantation is an example of how tactical victories often lead to operational and strategic failure. It remains difficult to “win,” at least in the conventional military sense, in partisan warfare when the population rejects the messages of the occupying force.

[1]The basis of this article is drawn from: Christopher Pieczynski, The Skirmish at James’s Plantation, A Research Paper Submitted to the Virginia Beach Historic Preservation Commission, February 1, 2019, https://www.vbgov.com/government/departments/planning/boards-commissions-committees/Documents/VA%20Historical%20Preservation/Research%20Grant/The%20Skirmish%20at%20James’s%20Plantation.pdf

[2]For readable accounts of the Southern Campaign see, John Buchanan, The Road to Guilford Courthouse: The American Revolution in the Carolinas (New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc. 1997) and his follow on, The Road to Charleston, Nathanael Green and the American Revolution (Charlotteville: University of Virginia Press, 2019).

[3]Henry Clinton and William B. Willcox, ed., Extract from Sir Henry Clinton’s Instructions to Brigadier General Arnold, December 14, 1780. The American Rebellion (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1954), 482-3. For a contemporary analysis of Arnold’s Richmond Campaign and operations in Virginia during this period see: Mark Edward Lender and James Kirby Martin, A Traitor’s Epiphany: Benedict Arnold in Virginia and His Quest for Reconciliation, Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 125, no. 4, (2017): 314-357.

[4]Johann Ewald and Joseph P. Tustin, ed & trans., Diary of the American War (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979), 277. Ewald stated, “ . . . General Arnold had asserted that when he made an appearance the people would change their minds in droves.”

[6]Lender & Martin, Traitor’s Epiphany, 318.

[7]The editor of the Cornwallis Papers determined Sir Henry Clinton had 32,000 troops in 1780 but required 14,000 to 17,500 to safely hold New York, with others committed to East Florida, West Florida and Georgia, limiting the forces available to employ in the Carolinas and Virginia. Ian Saberton, Britain’s Last Throw of the Dice Begins—The Charleston Campaign of 1780, Journal of the American Revolution, October 12, 2020, https://allthingsliberty.com/2020/10/britains-last-throw-of-the-dice-begins-the-charlestown-campaign-of-1780/

[8]Clinton, Extract, American Rebellion, 482-83.

[9]“Note 176. Troops under Brigadier-General Arnold,” in Robert Beatson, Naval and Military Memoirs of Great Britain, from 1727 to 1783, VI, (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees and Orme, 1804), 213.

[10]Ewald, Diary, 255 & 258, Other sources suggest the number of troops was in the 1,600 to 1,800 range as outlined in Note 3, Ewald, Diary, 420.

[11]Ewald, Diary, Note 2, 420.

[12]Clinton, Extract, American Rebellion, 482-83.

[13]Walter Clark, ed., Letter from Benedict Arnold to Henry Clinton, February 13, 1781, State Records of North Carolina, 17, (Goldsboro, NC: Nash Bros., Book and Job Printers, 1898), 985. Extract available, https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr17-0297

[15]Ibid., Letter from Benedict Arnold to Henry Clinton, February 25, 1781, 987-8. Extract available, https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr17-0300

[16]Clinton, American Rebellion, 482-483.

[18]Clinton, The American Rebellion, 482.

[20]Drummond Bell and Mike Cecere, Virginia’s Swamp Fox, August 10, 2021, Journal of the American Revolution, https://allthingsliberty.com/2021/08/virginias-swamp-fox-captain-amos-weeks-of-princess-anne-county/

[21]Ibid., 174, Simcoe referred to Weeks as a “New Englander,” with no further explanation; his marriage in 1779 reflects he was a resident of Princess Anne County at that time, Elizabeth B. Wingo, compiler, Marriages of Princess Anne County, Virginia: 1749-1821 (Norfolk, VA: Elizabeth B. Wingo, 1961), 103.

[22]John Graves Simcoe, Simcoe’s Military Journal: A History of the Operations of a Partisan Corps, called the Queen’s Rangers (New York: Bartlett & Welford, 1844), 249, https://ia902607.us.archive.org/2/items/simcoesmilitary00simcgoog/simcoesmilitary00simcgoog.pdf and Ewald, Diary, 323.

[24]Patrick H. Hannum, Recognizing the Skirmish at Kemp’s Landing, December 17, 2017, Journal of the American Revolution https://allthingsliberty.com/2018/12/recognizing-the-skirmish-at-kemps-landing/

[25]Simcoe, Journal, 173-4, https://ia902607.us.archive.org/2/items/simcoesmilitary00simcgoog/simcoesmilitary00simcgoog.pdf, and Ewald, 279.

[26]Dauges Bridge is today the stie of a modern concrete highway bridge along Princess Anne Road and also hosts a small city park, renamed Doziers Bridge, complete with a canoe and kayak launch suitable to explore the marshland Ewald traversed.

[31]Simcoe, Journal, 173-7 and Ewald, Diary, 284.

[33]Pungo Chapel was located near the modern intersection of Princess Anne Road and West Neck Road.

[35]Ibid., 286 and Simcoe, Journal, 174.

[36]For and overview of Dunmore’s Proclamation see: Patrick H. Hannum, Dunmore’s Proclamation: Information and Slavery, Journal of the American Revolution, December 30, 2019, https://allthingsliberty.com/2019/12/lord-dunmores-proclamation-information-and-slavery/

[37]Proclamation of Benedict Arnold [21 Feb 1781], Jack Robertson Papers, Stephen Mansfield Archives, Virginia Wesleyan University, and Ewald, 286.

[38]“To Thomas Jefferson from Robert Lawson, 15 February 1781,” Founders Online, National Archives, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-04-02-0776. [Original source: Julian P. Boyd, ed., The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 4, 1 October 1780 – 24 February 1781 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1951), 616–618].

[41]Johann Ewald, Treatise on Partisan Warfare, Translation, Introduction, and Annotation by Robert A. Selig and David Curtis Skaggs (New York: Greenwood Press, 1991), 81.

[43]Pension Application of John Brown, S6753, Southern Campaign Revolutionary War Pension Statements and Rosters, http://www.revwarapps.org/.

[44]Pension Application of William Bryan, S6760, Southern Campaign Revolutionary War Pension Statements and Rosters, http://www.revwarapps.org/.

[45]Journal entry Friday, December 19, 1783. Journal of the House of Delegates of the Commonwealth of Virginia (Richmond, VA: Thomas W. White, 1828), 74. https://archive.org/details/journalofhouseof178186virg. “Resolved, that it is the opinion of this committee, That the petition of William Hill, praying relief in consideration of the loss of his right arm whilst serving as a volunteer in a corps commanded by Captain Amos Weeks from the county of Princess Anne, is reasonable; and that the petitioner ought to be allowed half pay for his present relief from the time he was wounded, to the 8th instant; and also, that he ought to be put on the list of pensioners.”

[46]Pension Application of Thomas Bonney, S6688, Southern Campaign Revolutionary War Pension Statements and Rosters, http://www.revwarapps.org/.

[47]Ewald, Diary, 286-294, and Simcoe, Journal, 175-186.

[48]Lender and Martin, Traitors Epiphany, 350.

[49]Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Joint Publication 3, Joint Operations (Washington, DC, January 17, 2017), I-2. VII-27 & A-1 to A-4.

2 Comments

The writers keep referring to Arnold’s objectives in Virginia. Arnold had ONE objective in Virginia: capture the entire Legislature (which was composed largely of men who were using the war as a smokescreen to rip off Indian lands), so that new elections could empower a new Legislature to sign the peace treaty (complete independence with no strings attached) offered to Congress in March 1779. Arnold had been appalled that Congress had turned down the offer, and that is why he switched sides — to give Congress the kick in the pants they deserved. Once Virginia signed, everyone else would sign, he thought.

AMAZING COLLECTION OF INFORMATION REF.ARNOLD IN VIRGINIA – AND LATER ON. NEEDS TO BE READ THREE OR FOUR TIMES — TO “DIGEST” THE MAIN POINTS OF THIS “VAST WORK”… NICELY WRITTEN ‘PAGE OF EARLY AMERICAN HISTORY’ — RESPECTFULLY – HENRY PAISTE. 10/14/21

PARTICULARLY INTERESTING TO ME PERSONALLY- AS MY RELATIVE/PEGGY SHIPPEN- MARRIED BENEDICT ARNOLD -PRIOR TO HIS LEAVING FOR BRITAIN. !!!

Respectfully – Henry T. Paiste, iii