Anyone who has ever tackled genealogical or historical research knows that the process is very much like putting a jigsaw puzzle together or working on a cold case crime. Sometimes you are fortunate and all of the pieces or clues are available and easily come together to produce a definitive result. More often than not, one finds that pieces or clues are missing, possibly to be discovered through exhaustive research but sometimes never to be found because they simply no longer exist. Such appears to be the case with Captain Amos Weeks.

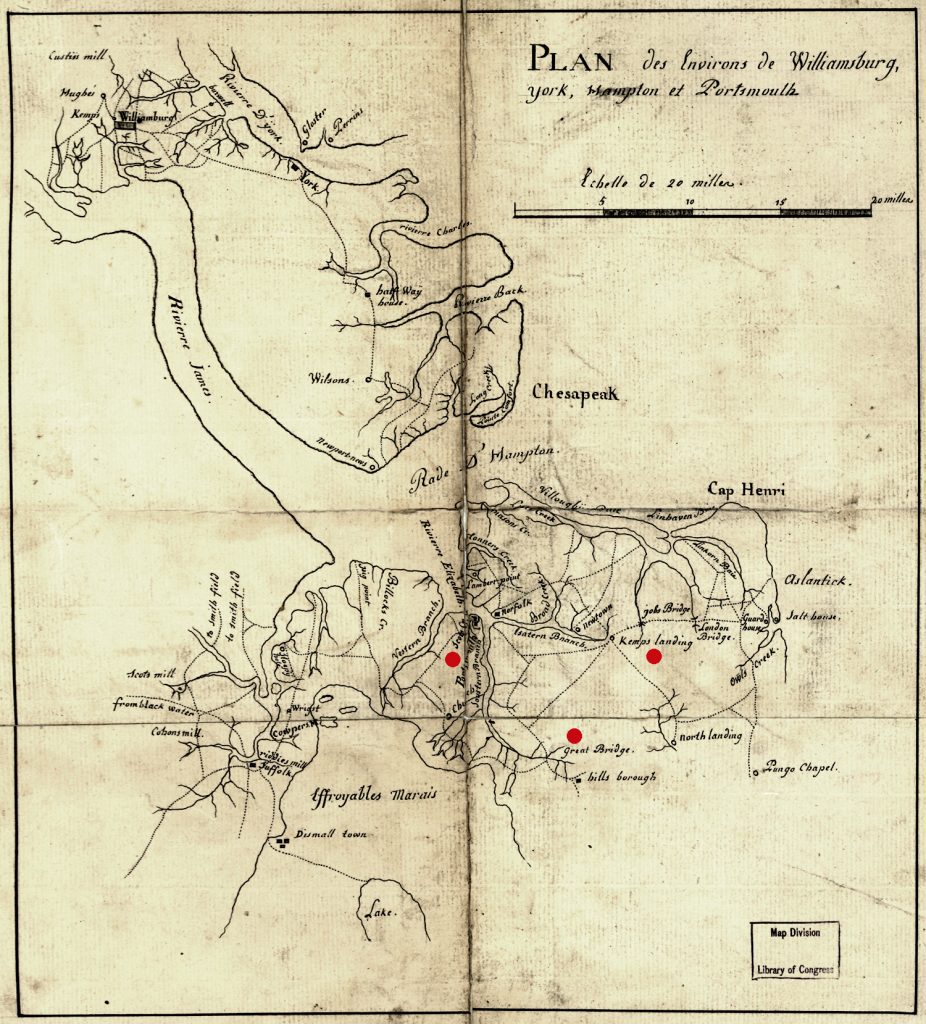

We first came across the name Amos Weeks in reading about the Revolutionary War in Princess Anne County, Virginia in 1781. Two published primary sources, the journal of Capt. Johann Ewald and the journal of Lt. Col. John Graves Simcoe, provided interesting detail on British operations during Benedict Arnold’s occupation of Portsmouth in the winter and spring of 1781. We noted that both officers were particularly interested in capturing a militia commander named Amos Weeks who had staged a series of ambushes upon British detachments in Princess Anne and Norfolk County.

Curious to learn more about this bold American militia commander, we began our jigsaw puzzle and immediately noticed something unique. One would normally expect a captain of militia in the Revolutionary War to be a person of some standing in his local community, involved in local governance or with property and a higher social status than your typical rank and file soldier. If this was the case, then one would expect a paper trail to shed more light on the officer. Alas, our search for records of Captain Weeks in Princess Anne County prior to 1775 has been disappointing.

Lieutenant-Colonel Simcoe’s description of Weeks as “a New Englander” offers a possible explanation for the lack of documentation on him in Virginia prior to 1775. The first evidence of Captain Weeks’ presence in Princess Anne County comes from pension statements of men who served under him in the militia. While such statements, often given fifty years or more after the fact, can frequently be flawed by mistaken memories, patterns sometimes emerge, and we found such patterns.

The only pension statement for 1775 pertaining to Captain Weeks came from Charles Smith, who recalled in 1832 that,

He entered the service of the United States in the year 1775 under Capt Amos Weeks, that the duty he did consisted in keeping guard chiefly, that he was marched to Norfolk twice, while that place was blockaded by the british, that he was in a skirmish with the enemy on one occasion at Norfolk.1

In support of the pension application of Dr. Samuel Harris of the 4th Virginia Regiment, John Brown of Princess Anne County swore in an affidavit that

In the latter end of 1776 enrolled himself in a company of Volunteers commanded by Captain Weeks which was raised in the County of Princess Anne and at that time was in active service in norfolk and the surrounding neighbourhood.2

Additional records shedding light on the militia of Princess Anne County in 1775 and 1776 are scarce, but the recollection of two separate pension applicants suggest that Captain Weeks was in the field with the Princess Anne militia in the first year of the war.

Captain Weeks’ involvement with the Princess Anne County militia apparently ended sometime in 1776 or perhaps early 1777, giving way we believe with a foray into privateering.

In mid-April 1777 the log of the British warship Glasgow recorded that it had captured, “a Yankee Privateer, called the Henry, Amos Weeks Commander, of six Carriage Guns, six Swivels, two Cohorns & 23 Men.”3 Glasgow had encountered the privateer on April 18 in the West Indies and gave chase. The following day Glasgow spotted the vessel “standing in for the Land,” and sent a longboat to seize it, but the Americans fired upon them and the chase resumed. By afternoon the privateer had “run ashore, and all hands employed [in] plundering her.”4 The American crew had fled ashore and tried to take everything they could of value with them. The British seized the abandoned privateer as a prize and learned, likely from documents left on board, that its commander was Amos Weeks.5

Whether this Amos Weeks was the same Capt. Amos Weeks in Princess Anne County is difficult to determine with certainty, but circumstantial evidence suggests it was. Aside from the matching names, the gap in Captain Week’s militia service in 1777, combined with yet another privateer account in August 1777 involving a “Capt. Weeks, in a Privateer from Virginia,” adds credence to the possibility that Captain Amos Weeks in Princess Anne County had taken up privateering in 1777.6 Additionally, Amos Weeks was involved in 1780 in an attempt to build a ship in Princess Anne County, yet another suggestion that he was somehow tied to the sea.7

Connecting these dots, we conclude that Weeks lost his vessel, Henry, in the West Indies. He, and likely his crew, either obtained a new vessel or somehow made their way back to Virginia, and Weeks returned to privateering by August 1777. His involvement was brief, however, for several pension accounts as well as government papers place him once again in command of a militia company in Princess Anne County by 1778.8

Little is known of Captain Weeks’ activities in 1779-80, but he appears frequently in accounts by Captain Ewald and Lieutenant Colonel Simcoe during the winter of 1781.

Brig. Gen. Benedict Arnold, the infamous American traitor, arrived in Virginia in late December 1780 with 1,200 troops and several warships. They quickly proceeded up the James River, briefly occupied Richmond, the new capital, and seized and destroyed a large amount of military stores. They then made their way back down the river, reinforced by another 600 troops who had been delayed by bad weather, and occupied Portsmouth in mid-January.

To protect this new post, Arnold established outposts at Great Bridge and Kempe’s Landing and sent frequent patrols into Norfolk and Princess Anne County to scout and forage. It was the demise of one of these foraging parties, at the hand of Captain Weeks and his men, that first attracted the attention of Captain Ewald, commander of a company of German Jägers (riflemen). Ewald recalled that an artillery officer had been killed and several artillerymen captured by a party of rebels while foraging near Pallet’s Mill east of Kempe’s Landing. Ewald noted that,

This enemy party is said to have been from a light corps commanded by a certain Major Weeks to whom the country people are greatly devoted, partly from inclination and party from fear. In the countryside he is considered an excellent officer and a good partisan. There was much talk about him at Kemp’s Landing but we laughed because we had neither seen nor heard anyone. Afterward, we were astonished over the trick he had played in our rear.”9

Lieutenant Colonel Simcoe, who commanded the Queen’s Rangers, a combined force of provincial cavalry and infantry, noted on February 10, 1781 that, “The disaffected inhabitants of Princess Ann for the most part, had left it, but it was much infested by a party under the command of a New Englander, of the name Weeks.”10 Captain Ewald misidentified as a major:.

The news came in from Princess Anne County that Major Weeks was spreading ruin in the area and severely harassing the few good loyalists. The communication between Portsmouth and Great Bridge was made unsafe.11

The observations of Ewald and Simcoe are supported by pension statements of men who served under Weeks in 1781. Thomas Williams volunteered with Weeks (he spelled the name Wicks) in January 1781 and remembered that they “had a small skirmish in February and another soon after in Kempsville.”12 Williams was captured in early March by British cavalry, probably Simcoe’s Rangers.

John Murphy of Princess Anne County recalled serving under “Captain Wicks in the winter of 1781:

He was pretty constantly engaged in duty and whilst in Princess Anne County was occasionally relieved from duty but at brief intervals during which the deponent worked at his trade as a Silver Smith. Whilst under Captain Wicks his Company was engaged as a scouting Company in Princess Anne County affording protection to the inhabitants of the County from British depredations.13

In mid-February, Gov. Thomas Jefferson learned Captain Weeks’ activities via a report from two local militia officers passed on to him by militia general Robert Lawson. Although Weeks was not specifically named, there is little doubt that the report was about the activities of Captain Weeks:

I . . . received a Letter . . . from Colonels Godfrey and Thoroughgood, informing, that the number of Militia collected by them, from the Counties of Norfolk and P. Ann was inconsiderable; with which number they had join’d General Gregory, but at the same time, they acquainted me, that there was a body of Militia collected in P. Ann, who had prevented the Enemy from foraging, in small bodies, and that they had gain’d several small advantages over their foraging parties; and operated as a great check upon them in that quarter.14

Encouraged by this bold opposition, some of the only resistance offered to General Arnold in February, Governor Jefferson inquired with General Steuben, the ranking continental officer in Virginia, whether there was a way to assist and encourage Captain Weeks and his men to continue their efforts.15

Others recognized the disruption caused by Captain Weeks. General Arnold himself was exasperated by his exploits and, according to Captain Ewald, “decided to send two parties [into Princess Anne County] one under Colonel Simcoe and the other under myself, in order to drive away the honorable gentleman.”16

The plan was to catch Captain Weeks and his troops in a pincer movement. Simcoe marched from Kempe’s Landing eastward with 200 infantry and 40 cavalry to draw Week’s attention while Ewald marched eastward from Great Bridge though the Devil’s Elbow Swamp with 200 infantry and 30 cavalry to get behind Weeks and trap him.17

Ewald recalled that his detachment set out in the early morning darkness of February 14, 1781:

The men had to march in single file, constantly going up to their knees in the swamp. We had to climb over countless trees which the wind had blown down and that often lay crosswise, over which the horses could scarcely go. They had to be whistled at continually to prevent them from going astray. Men and horses were so worn out that they could hardly go on when I happily left this abominable region behind.18

They reached the plantation of a relative of their Tory guide around 9 a.m. where a coded message from Simcoe instructed them to halt and await further instructions. Ewald was ordered to proceed through Dauge’s Swamp early the next morning in hopes of catching Captain Weeks by surprise at Dauge’s Bridge.19 Ewald described the difficult passage through nearly three miles of swamp:

Although I had crossed the first swamp with great difficulty during the night, this last passage surpassed the first one very much with respect to all hardships. The men had to wade constantly over their knees in the swampy water and climb over the most dangerous spots with the help of fallen and rotted trees. At times there were places such, that if a foothold were missed, a man could have suffocated in the swamp. I had to cross a flooded, swampy cypress wood with the cavalry, a quarter of an hour further to the right, where one had to ride continually in water over the saddle. At the end of the swamp, wither our two guides led us safely at the same time, there was a long causeway—a good quarter hour long—which because of its great holes was just as difficult for the horses and men to cross as the swamp had been.20

Ewald surprised the inhabitants of a small house who “gazed in astonishment at the sight of us, when they learned the way which we had taken.” They informed Ewald that Captain Weeks had burned the Dauge Bridge and withdrawn.21 He was just three miles away, near Jamison’s plantation with six to eight hundred men, Ewald was told, and the bold German officer resolved to bag him. “After I had told my men that we must fight, as we had no way to retreat,” recalled Ewald, “we marched at once.”22

Ewald ordered his cavalry, supported by twenty infantry, to march straight to the plantation via a direct road while he led the rest of his force of 180 infantry through woods to outflank Weeks. Captain Shank, who led the cavalry, was to “draw the attention of the enemy upon himself,” and skirmish with him to allow Ewald to circle around and attack them by surprise.23 The effort did not go as planned. Captain Ewald recounted,

I made my way through the wood with the 180 jagers and rangers, but I had marched scarcely eight hundred to a thousand paces when I heard strong rifle fire. The man from the small house informed me that the enemy must be situated at James’s, rather than Jamison’s plantation, which was close to our left, since there was a crossroad from London and Northwest Landing at this plantation.

I quickly formed a front on the flank and directed my men to fire a volley as soon as they caught sight of the enemy and then boldly attack the foe with the bayonet and hunting sword. I ordered the jagers to disperse on both flanks and kept the rangers in close formation. We had not passed five to six hundred paces through the wood when we saw the enemy in a line facing the side of the highway to London Bridge, firing freely at Captain Shank’s advance. In doing so, they carelessly showed us their left flank. I got over a fence safely without being discovered by the enemy. Here I had a volley fired, blew the half-moon, and shouted, ‘Hurrah!’ I scrambled over a second fence and threw myself at the enemy, who was so surprised that he impulsively fled in the greatest disorder into the wood lying behind him.

At that moment the gallant Captain Shank advanced with his cavalry, ably supported by Lieutenant Bickell with his twenty foot Jagers. Some sixty men were either cut down or bayoneted by the infantry. We captured one captain, one lieutenant, four noncommissioned officers, and forty-five men, some sound and some wounded. All the baggage, along with a powder cart and a wagon loaded with weapons, was taken as booty by the men. I ordered Lieutenant Bickell with all of the foot jagers to quickly follow the enemy into the wood. He followed him until night fell and brought back seven more prisoners. On my side, I had three jagers and two rangers wounded and one horse killed.24

Ewald reported his success to Lieutenant Colonel Simcoe, who joined Ewald early in the morning of February 16. From the American prisoners, Ewald learned that Captain Weeks commanded 520 men and that they were to rendezvous at Northwest Landing.25 Ewald attempted to recruit the prisoners to the British cause, but noted that Captain Weeks’ “people were so devoted to him that none of them were willing to enlist in our service.”26

Lieutenant Colonel Simcoe was determined to press Weeks and set out ahead of Ewald, whose men were given a bit longer to rest. Simcoe headed towards Pungo Church along the only road Weeks could take to reach Northwest Landing. In the afternoon, Ewald reunited with Simcoe at the church, left a small detachment in ambush, and proceeded east to search for Weeks. Simcoe marched to the plantation of John Ackiss, a Princess Anne County militia officer, with the same mission.27

Less than an hour into his march, Captain Ewald was informed by one of his flankers that several blue coated sentries were observed on the right. Ewald described what occurred next.

I immediately sent out the jagers in two parties, hurrying to the right and left, in order to seek out and attack the enemy. I myself took the rangers and followed the road straight toward the plantation, which I perceived in the distance. The party on the right ran into the enemy,and the other party, in accordance with previous orders, hastened to the spot where the firing broke out. I found the enemy in full flight, running through a marshy meadow to a wood. Two of their men were killed and a lieutenant with five men captured. Had Lieutenant Bickell seized another officer who stood a few paces away instead of the lieutenant, the commander of the party—Major Weeks himself—would have been captured. But since he was not as well dressed as the lieutenant, he was not taken for an officer. Just before, a jager had killed his horse.28

Captain Weeks and most of his men scattered and escaped, once again eluding Ewald’s grasp. Despite his success against him, the German commander remained impressed with his adversary, noting that,

This man, whom I had the good luck to chase all around, knew the countryside better than I could ever know it. That was evident from the positions he took, for a retreat always remained open to him in the impassable woods which he alone knew. But on this occasion, my spies were better than his; and luck, on which everything depends in war, was on my side.29

With their enemy thoroughly dispersed, Simcoe and Ewald headed back to Portsmouth, satisfied that they had adequately suppressed Weeks and his men. Within days of their return, General Arnold issued a proclamation to the inhabitants of southeast Virginia offering paroles and pardons to those who, “have heretofore been in Arms, and borne Offices, under the usurp’d Authority of the Rebel Legislatures.”30 Arnold specifically signaled out Captain Weeks and his men with an ultimatum, declaring that,

A Party of Men being in Arms under the Command of an Amos Weeks, at Kemps, has Authority to inform them, that if they submit themselves, within six days, receive their paroles, and demean themselves hereafter, as quiet Subjects, they will be receiv’d and their Property unmolested. But that if after the time committed, should they, or any other small Parties, infect the County, they will be proceeded against with the utmost Rigeur, and Reprisals made upon them and their Families for any Damages the peaceable Inhabitants may sustain from their unwarrantable Proceedings.31

The day after Arnold’s proclamation, Captain Weeks and a few of his men arrived in Gen. Isaac Gregory’s camp at the Northwest River Bridge.32 Whether these few men were all that was left of his force or simply a detachment that accompanied him is unclear. What is clear is that Captain Weeks did not accept Arnold’s pardon and continued to resist. Weeks informed Col. Josiah Parker in early March that he had 300 troops willing to fight, but Princess Anne County would be lost to the enemy if help were not provided soon.33

A week later, some of Captain Weeks’ men engaged in yet another heated skirmish with Captain Ewald on the road between Great Bridge and Kempe’s Landing. Ewald had positioned his men to ambush Weeks and recorded,

As soon as night fell I had to lie in ambuscade in the bushes on this side of Great Bridge along the road from Kemp’s Landing to Great Bridge. . . . As soon as he [Weeks] had crossed the swamp, I was to attack Major Weeks with the jagers, one hundred men of the infantry and all the cavalry of the rangers.

The night was very dark but still. After midnight, about two o’clock when I had just taken my measures for an ambuscade, a number of shots were heard in the direction of Kemp’s Landing. I immediately hurried there, forming a vanguard of all the infantry and ordering the cavalry to follow, and behind them the jagers. Since the countryside was greatly cut through by woods, I could not use the jagers because of the dark night.

I had scarcely marched two English miles up to Hopkin’s plantation when I was informed that some people were approaching. Hereupon I commanded, ‘March! March! Lower Bayonets!’ Whereupon a ‘Who’s There?’ was heard, and the enemy fired a small volley. But at that instant, when I thought of fighting hand to hand with him, he scattered into the woods. From the two men who were captured I learned that they were from Weeks’ corps and were detached to cover the rear, while he attacked Captain M’Kay marching from Kemp’s Landing. The enemy had closed in on Captain M’Kay but had withdrawn after hearing the firing from my direction. Since I did not deem it advisable to follow the enemy because of the dark night, I marched back to my former post.34

Captain Weeks had attempted to ambush a detachment of British troops out of Kempe’s Landing at the same time Captain Ewald laid in ambush for him. Both plans were thwarted with little loss for either side.

The arrival of General LaFayette in March gave hope to the Americans that they might be able to capture Benedict Arnold and his entire force, but British reinforcements soon arrived to dash such hopes and operations shifted back up the James River when 2,500 British troops marched to Petersburg in April.

Although we know little of the activities of Captain Weeks during this period, Captain Ewald, recovering from a leg wound suffered in mid-March in a skirmish outside of Portsmouth, recorded that Weeks was still active. He noted in mid-May that,

Since Major Weeks appeared again in Princess Anne County with his Corps, he has severely mistreated the inhabitants who had renewed their oath of allegiance under Arnold. He threatened to burn the English hospital at Norfolk, which could very easily be done because some twenty captured officers and several hundred privates were lodged there for safekeeping.35

Although not fully recovered from his wound, Ewald took it upon himself to command the troops posted at the hospital and defend it against Weeks, prompting an audacious response from the rebel commander. He recalled,

Mr. Weeks appeared several time in the area. Once he sent word to me through a wench that he hoped to square accounts with me again in Norfolk. But since he always found that I was ready for his reception and awaited his service, he let well enough alone with nightly alarms.36

With the shift of British operations to the central part of Virginia in the summer of 1781, it appears that the activity of Captain Weeks decreased. Another intriguing possible explanation for the relative disappearance of Captain Weeks in June and July is that he may have accepted an appointment from Governor Jefferson to command a detachment of rangers, likely riflemen from the western counties. Although no record of such an appointment has been discovered, a letter written in 1782 by Gov. Benjamin Harrison concerning Weeks suggests strongly that Jefferson offered such an appointment. Writing to the Speaker of the House of Delegates in June 1782 on behalf of Weeks to assist him in obtaining reimbursement for expenses incurred in 1781, Governor Harrison wrote,

I do myself the honor to inclose you a Pay roll of Capt. Weeks. This Officer appears to have been appointed by Governor Jefferson to take command of a company of Rangers, and report(s) from every quarter represents him to have rendered the most essential service. I thought it advisable to lay it before the General Assembly. The general department of Capt. Weeks and the many essential services he has rendered seem to call for Justice from his Country.37

It appears from this letter and numerous pension statements that Amos Weeks was promoted to major and given an independent command. Benjamin Long of Caroline County recalled that in the fall of 1781 he was, “attached to a light infantry rifle company commanded by Major Weeks in which he continued about four weeks.”38 Several other pension applicants placed Major Weeks in Gloucester County in the fall of 1781 in command of light infantry.

Lt. Col. John Graves Simcoe places Major Weeks in Gloucester in mid-August. He recalled that soon after the British army arrived in Yorktown and Gloucester, he was made aware of the presence of Weeks. Simcoe, writing in the third person, described his reaction to the news.

Lt. Col. Simcoe, on his return one day from Abington church, was informed that Weeks, now stiled Major, with a party of the enemy, had just arrived within a few miles; he instantly pressed on with the cavalry to attack him, ordering Capt. Ewald to proceed to his support as fast as possible with the Yagers and infantry. On his arrival near the post, he had the good fortune to push a patrole, which came from it, so rapidly as to follow it into the house where Weeks lay, who, with his men, escaped in great confusion into the woods, leaving their dinner behind them; an officer and some men were made prisoners.39

Captain Ewald participated in the attack on Weeks and recorded his own account:

On the 18th Colonel Simcoe went out with the jagers and rangers to conduct a foraging on the plantation of Colonel [Warner] Lewis. [Ewald learned that] Major Weeks with five hundred riflemen and one hundred horsemen had just taken post at Turas [?] plantation, four English miles from Lewis’s House. I took this news to the colonel [Simcoe] who quite impulsively took fifty horse to surprise this party, and I followed him with two hundred rangers at quick step. One English mile from the enemy position the colonel ran into an enemy patrol of two men, who ran back. But the colonel, and I with most of the men who could run swiftly, arrived at the same time as the patrol in the camp of the enemy, who had no time to get their arms and tried to save themselves. I tried to create still greater confusion by continuous haphazard firing, and we became masters of the whole enemy camp. We took one lieutenant and twenty-two men prisoner, captured forty-three horses and all the baggage, and smashed all the saddles and weapons.40

Although Major Weeks and his men got the worst of this engagement, their opportunity for revenge soon arrived.

The situation for the militia posted on the north side of the York River in Gloucester County was mostly one of observation. Gen. George Weedon commanded and had little faith that the militia would stand in a contested engagement, so he kept the bulk of his force a good distance away from Gloucester Point, where the British were entrenched. Major Weeks, however, appears to have been more active than the main body and was discouraged by the reaction of Gloucester’s inhabitants to British presence. He wrote to Thomas Newton of Princess Anne County in mid-September to comment on the situation in Gloucester. This letter has long been misinterpreted to have been written from Princess Anne County about the inhabitants there, but the pension statements and accounts of Simcoe and Ewald, as well as Major Weeks’ use of the term headquarters, all support that he was writing about Gloucester County.

I have Seen into the Situation of People and I find a Great Many Disafected in the County, Whom I think Should be Brought to Justice, And I am Getting together My Men Upon that intent and Capt. Butt’s Men Will Join me as Soon as Possible and then I intend to Go Amongst them and Bring as Many as I Gett to Head Quarters, Where I hope that they Will Meett with that Punishment Due to a Tory and a Enemy to the Country. I shall be very Glad if you will acquaint the Governor With My Proceedings as soon as Possible, Which shall not be Wanting in Any thing that Lays in My Power. I have no news to Write.41

Two weeks after he wrote this letter, Major Weeks found his opportunity to avenge the loss he suffered in August at the hands of Simcoe and Ewald.

The Battle of the Hook (also known as the Battle of Gloucester Point) began on the morning of October 2, when a party of General Weedon’s mounted militia stumbled upon the rear guard of a large British foraging party a few miles from the British earthworks at Gloucester Point.42 The British force, commanded by Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton, was in the midst of a profitable morning of foraging when militia horsemen spotted them and raced back to report their activity. The Virginia horsemen soon met the Duke de Lauzun with a detachment of French hussars (cavalry) in advance of the allied troops marching towards Gloucester Point. French reinforcements had arrived in mid-September and with them came a more aggressive stance against the enemy. Lauzun led his cavalry forward to investigate and encountered

A very pretty woman at the door of a little farm house on the high road; I went up to her and questioned her; she told me that Colonel Tarleton had left her house a moment before; that he was very eager to shake hands with the French Duke. I assured her that I had come on purpose to gratify him.43

Lieutenant Colonel Tarleton was aware of Lauzun’s approach; a rearguard patrol had reported his presence. As the French cavalry drew closer, “a column of dust . . . became visible.”44 Lauzun remembered that he had not yet gone, “a hundred steps” from the little farm house when

I heard pistol shots from my advance guard. I hurried forward at full speed to find a piece of ground where I could find a line of battle. As I arrived I saw the English cavalry in force three times my own.45

Tarleton’s wagons, loaded with forage and escorted by the bulk of his detachment, were already on their way back to Gloucester Point when Lauzun appeared on the field. Tarleton ordered the wagons to continue on but, “Part of the legion cavalry . . . [the 17th Light Dragoons] and Simcoe’s dragoons, were ordered to face about in the wood, whilst Lieutenant-Colonel Tarleton reconnoitered the enemy [with a troop of horse].”46

It was probably these cavalry detachments, located on the edge of the wood, that Lauzun saw in the distance when he first arrived on the field. Positioned between the British cavalry and Lauzun was Tarleton with his single troop of horsemen, reconnoitering the situation. Lauzun charged forward to engage Tarleton and recalled,

Tarleton saw me and rode towards me with pistol raised. We were about to fight single handed between the two troops when his horse was thrown by one of his own dragoons pursued by one of my lancers. I rode up to him to capture him; a troop of English dragoons rode in between us and covered his retreat, he left his horse with me.47

Tarleton recounted that while he and Lauzun clashed

The whole of the English rear guard set out full speed from its distant situation, and arrived in such disorder, that its charge was unable to make an impression on the Duke of Lauzun’s hussars.48

Tarleton remounted and ordered a withdrawal, pursued by Lauzun and his horsemen. Musket fire from forty British infantry posted in a thicket “restrained” Lauzun, who halted his charge.49 This allowed Tarleton to rally his cavalry, reverse direction, and once again charge upon Lauzun. Tarleton recalled,

A disposition was instantly made to charge the front of the hussars with one hundred and fifty dragoons, whilst a detachment wheeled upon their flank: No shock, however, took place between the two bodies of cavalry; the French hussars retired behind their infantry and a numerous militia who had arrived at the edge of the plain.50

The “numerous militia” that Tarleton observed were approximately 160 Virginians under Lt. Col. James Mercer. With Mercer was Maj. Amos Weeks, in command of four companies of militia.51 They arrived on the scene just in time to see the French horsemen repulsed. Mercer recalled that his men “were at first somewhat startled to find the French horse retreating so rapidly.”52 The Virginians quickly recovered their nerve and deployed to meet the oncoming British. Mercer proudly recalled that his men formed

with great celerity & good order, & commenced firing, one half on the cavalry on the right, & the other half on the infantry advancing rapidly thro’ the wood. The horse of the enemy had approach’d within 250 yards & the infantry were not at more than 150 yards distance when the firing began. No regular troops cou’d behave with more zeal & alacrity than this corps of Militia; their spirits had been rais’d by running them up, and being hurried into action without time to reflect on their danger, they discovered as much gallantry & order as any regular corps that I ever saw in action. Fortunately Tarleton did not like the reception prepared for him & at a critical moment sounded a retreat, when not 100 cartridges remain’d unexpended in the regiment.53

Each of the three sides involved in the engagement suffered losses. Lieutenant Colonel Mercer reported 2 killed and 11 wounded from his force of Virginia militia. Lauzun reported 3 killed and 16 wounded, while Tarleton claimed only one of his officers was killed and a dozen soldiers were wounded.54 Disappointingly, aside from the pension statements of several of his men, we have no detailed account of Major Weeks’ actions in the engagement.

The British surrender at Yorktown just three weeks after the Battle of the Hook appears to mark the end of Major Weeks’ service in the Revolutionary War, service that has gone largely unrecognized except by his adversaries, who recounted many of his exploits in their own journals.

1“Charles Smith, Pension Statement S7559,” Southern Campaigns of the American Revolution Pension Statements and Rosters, revwarapps.org.

2Samuel Harris Pension Statement, VAS11, “Affidavit of John Brown,” ibid.

3William J. Morgan, ed., “Journal of HMS Glasgow, April 18-19, 1777,” Naval Documents of the American Revolution, Vol. 8, (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Officer, 1975), 382.

6“Newbern, August 15, 1775,” Virginia Gazette, September 5, 1777.

7John Harvie Creecy, ed., Virginia Antiquary: Princess Anne County Loose Papers, 1700-1789, Vol. 1 (Bowie, MD: Heritage Books, 1997), 122.

8Pension Statements of John Brown, S6753, Thomas Bonney, S6688, Thomas Williams, S14843, and Charles Hartley, VAS 1429, Southern Campaign of the American Revolution Pension Statements and Rosters.

9Johann Ewald, Diary of the American War: A Hessian Journal, trans. and ed. Joseph P. Tustin (New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 1979), 278.

10John Graves Simcoe, Simcoe’s Military Journal: A History of the Operations of a Partisan Corps Called the Queen’s Rangers, Commanded by Lieut. Col. J.G. Simcoe, During the War of Revolution (New York: The New York Times and Arno Press, 1968), 164-165.

12Thomas Williams Pension Statement S14843, Southern Campaign of the American Revolution Pension Statements and Rosters.

13John Murphy Pension Statement R7514, ibid.

14Julian P. Boyd, ed., “Robert Lawson to Governor Jefferson, February 15, 1781,” The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. 4, (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1951), 617.

15Boyd, “Governor Jefferson to General Steuben, February 17, 1781,” The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, 4: 643.

30“Proclamation of Benedict Arnold, February 21, 1781,” Jack Robinson Papers, Stephen Mansfield Archives, Virginia Wesleyan University.

32Henry Muhlenberg, ed., “General Gregory to General Muhlenberg, February 23, 1781,” The Life of Major-General Peter Muhlenberg of the Revolutionary War(Philadelphia: Cary and Hart, 1849), 386.

33Muhlenberg, “Colonel Josiah Parker to General Muhlenberg, March 2, 1781,”The Life of Major-General Peter Muhlenberg, 392-394.

37H.R. McIlwaine, ed., “Benjamin Harrison to the Speaker of the House of Delegates, June 12, 1782, Official Letters of the Governors of the State of Virginia, Vol. 3 (Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1929), 249-250.

38“Benjamin Long Pension Statement,” S8846 f15VA, Southern Campaign of the American Revolution, Pension Statements and Rolls. See also the pension statements of Richard Hurst, S9593 f24VA, Leonard Claiborne, W3388. Fletcher Thomas, VA S8483, and Gabriel Hughes, W19836.

39Simcoe’s Military Journal, 239.

41William Palmer, ed., “Amos Weeks to Col. Thomas Newton, September 17, 1781,” Calendar of Virginia State Papers: Vol. 2 (Richmond: James E. Goode, 1881), 448-449.

42Banastre Tarleton, A History of the Campaigns of 1780 and 1781 in the Southern Provinces of North America (North Stratrord, NH: Ayer Company Publishers, 1999), 376.

43“Narrative of the Duke de Lauzun,” The Magazine of American History, Vol. 6 (1881), 52.

45“Narrative of the Duke de Lauzun,” 52.

47“Narrative of the Duke de Lauzun,” 52.

51Gabriel Hughes Pension Statement, W19836, Southern Campaign of the American Revolution, Pension Statements and Rolls.

52Gilliard Hunt, ed., “Colonel John Francis Mercer,” Eyewitness Accounts of the American Revolution: Fragments of Revolutionary History (New York: New York Times & Arno Press, 1971),58.

54Jerome Greene, The Guns of Independence: The Siege of Yorktown, 1781 (El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2005), 147.

6 Comments

Great article! From this account, Major Weeks certainly deserves more praise in comparison to other partisan commanders in the South. Certainly, he proved to be as effective and wily as more well known partisans in the Carolinas.

Very interesting and enjoyable article! Superb use of primary sources! Hopefully, your article may serve to unearth more information about this remarkable officer.

Great article! Well done! I am drawn to the mention of the “English Hospital” at Norfolk. Does anyone know if this was a building that survived the burning of Norfolk on 1 January 1776, or whether it had been built more recently? From the limited description in Ewald’s diary it would seem to have been a substantial enough building that it had survived the burning. Does anyone know where it stood? Please let me know at ne********@wi*******.com

John;

The British engineer map (Lt Stratton’s) map of Norfolk, 1781, is here:

https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3884p.ar145700/?r=0.089,0.689,0.488,0.395,0

Stratton’s practice was to draw “useful” structures in red. You can see by this map that there was not much “useful” left in Norfolk. The hospital was likely centered around one of the three red buildings depicted in Norfolk.

Little reconstruction occurred in Norfolk during the war. Many of the Scot/English merchant representatives returned to the UK, and others abandoned the town area. As the British army was only there for a seven months of 1781, its unlikely they built new.

Afraid we will have to draw our own conclusions.

Ewald, Diary of the American War, page 301, contains a map (hand drawn by Ewald) of Norfolk, titled: Plan of Norfolk, (1781). Map shows an estimated 30 structures along three streets. The hospital appears to be the military post located in the church and church yard. Near the center of Ewald’s map are the burned out remains of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church (see Ewald, page 426, note 42, church rebuilt 1785). This is a brick structure, reportedly the only structure to survive complete destruction in January-February 1776 (brick walls remained standing). Ewald states, (page 298), “This post consists of a burnt-out church which is surrounded by a brick wall. The interior of the ruins and the inner part of the wall have been provided with a kind of scaffolding, so that the occupiers can fire over the ruins and wall of the church.” The church is located at the intersection of St. Paul’s Blvd and City Hall Ave. A brick wall surrounds St. Paul’s today, see: https://www.visitnorfolk.com/listings/st-paul%E2%80%99s-episcopal-church/55/.

BG O’Hara reportedly had 1,000 sick negros (small pox) and sent 400 to Norfolk from Portsmouth when the British moved to Yorktown in August 1781. This gives support to the thought the church and church yard were used as both a hospital and military post. (See Cornwallis Papers, Vol. IV, page 52.)

Great article about a Revilutionary War officer who deserves the author’s attention. There is mention that that Captain Amos Weeks is a “New Englander”, and that could be quite true, because of the large Weeks family in Massachusetts and New Hampshire since the early 1600’s, including the busy seaport of Portsmouth NH, which would be a perfect place to run a privateer during the RevWar. Part of the Boston family actually left in 1657 for religious reasons, and settled in Long Island, becoming one of the few English-speaking families to learn Dutch, and become part of that old Dutch community which began to move up into the Hudson Valley, as New York City became too “Anglicized” in the early 1700’s. If the author finds other Weeks family members in New York regiments during the RevWar, they are usually Loyalists in regiments like the New York Volunteers.