Discussions about the American evacuation of Mount Independence and Fort Ticonderoga on the night of July 5, 1777 frequently address the question: could shot from artillery on Mount Defiance (commonly called Sugar Hill in the eighteenth century) reach Mount Independence and Ticonderoga? Those who believe it could use that potential as support for the decision to abandon the post. In contrast, nay-sayers often cite the lack of the threat as part of a criticism of the evacuation.[1] Few with either view offer any factual support for their position. A look at period documents provides a clear answer at both hypothetical and practical levels.

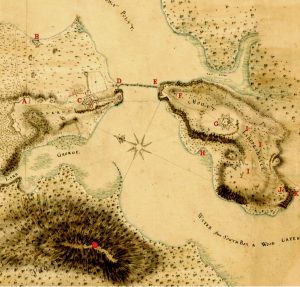

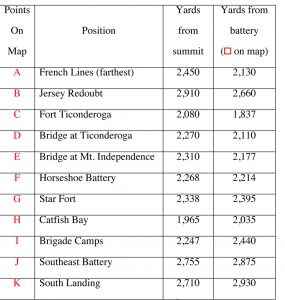

An investigation at the hypothetical level requires breaking the main question into two smaller queries. First, how far did the shot have to travel? General Burgoyne’s men built a battery just below the overlook on the modern access road on Mount Defiance 350 yards before the summit.[2] The table beneath the period map below prepared by British engineering officer Lt. Charles Wintersmith lists the ranges from the summit as well as the overlook to a group of targets spread around the full extent of Mount Independence and Ticonderoga. The location of each position is indicated by a matching red letter overlaid onto the map.

Distances to Various Locations (in yards)[3]

Distances to Various Locations (in yards)[3]

The range of the cannons is shown in the table below taken from three eighteenth century sources—The Artillerist’s Companion by T. Fortune published in 1778, An Universal Military Dictionary by Captain George Smith published in 1779; and A Treatise of Artillery by John Muller published in 1780. The table includes the ranges of two different size cannons (rated by the weight of an iron ball fired by the cannon)—12-pounders (two of which the British wrestled up Mount Defiance) and 6-pounders (included because the Americans conducted a test with that size cannon and the British army made extensive use of 6-pounders).

With this information, one can compare the ranges of the cannons and the distances to the various American positions. Clearly, all positions were beyond the “Point Blank” range of the guns. But all were within the “Utmost” range of even a 6-pounder placed along the northern half of Defiance’s ridgeline. Further, those ranges are for a level field. The cannons on Defiance sat 400 to 600 feet higher than any point on Mount Independence or Ticonderoga and the added elevation would have allowed the shot to travel much farther. There is no question that British shot could reach the American positions.

With this information, one can compare the ranges of the cannons and the distances to the various American positions. Clearly, all positions were beyond the “Point Blank” range of the guns. But all were within the “Utmost” range of even a 6-pounder placed along the northern half of Defiance’s ridgeline. Further, those ranges are for a level field. The cannons on Defiance sat 400 to 600 feet higher than any point on Mount Independence or Ticonderoga and the added elevation would have allowed the shot to travel much farther. There is no question that British shot could reach the American positions.

Armchair engineers comparing range and distance tables is all well and good but are there other period documents available that provide evidence of a practical nature? Serving on Lake Champlain in 1776, John Trumbull (the future artist) argued that shot from Mount Defiance could reach the American positions and he received permission to conduct some experiments. He loaded a 12-pounder with twelve pounds of powder and two balls and fired the gun from the north point of Mount Independence towards the summit of Defiance, a distance of 2,300 yards. “The shot were plainly seen to strike at more than half the height of the hill.” That would be about 2,000 yards from Mount Independence and an elevation about 300 feet higher than Trumbull’s cannon.

Next, Trumbull crossed back over to Ticonderoga for another test. He placed a 6-pounder on the glacis of the fort, charged it with 2 pounds, 8 ounces of powder and a single ball, and fired it at the summit over 2,000 yards away: “it was seen that the shot struck near the summit.” In both cases, the cannons fired uphill which dramatically reduced their ranges and the shot would have been even closer to its target had Trumbull fired at the future site of the battery. Even the 6-pounder would have hit, if not overshot, the site of the battery 1,750 yards away. Trumbull had convinced most doubters that the American positions could be bombarded from Mount Defiance.[4]

Absolute proof that shot from Defiance could reach the positions came during Col. John Brown’s Raid in September 1777. On the first day of the attack, Capt. Ebenezer Allen’s company captured the battery on Defiance and subsequently bombarded the fort.[5] If inexperienced American militia could get shot to fall on the positions, then trained British and German artillerymen certainly could.

There is an argument to consider based on the inaccuracy of period artillery, particularly at that range. It is quite true that the cannons frequently would not have hit what the gunners aimed at but, with so much development spread over the entire complex, much of the shot would have hit something and done some damage. Besides, put yourself in the place of an American soldier: it did not matter where the British aimed the cannon—any time a gun on Mount Defiance fired, every American would have wondered if he stood in the path of that shot. The distraction would have caused considerable consternation within the American positions.

To go off on a bit of a tangent, the possibility of artillery being able to reach positions should be only part of the discussion. In fact, the British did not even have cannons in place in the battery at the time of the evacuation.[6] The mere presence of enemy troops on Defiance made the American situation problematic. As noted by Lt. Col. Henry Brockholst Livingston, aid de camp to the American commander of the forts, Gen. Philip Schuyler, “This hill had such an entire command of Ticonderoga, that the enemy might have counted our very numbers.”[7]

As well as counting troops, the British could also survey the arrangement of the American forces. With insufficient numbers to defend either Mount Independence or Ticonderoga individually, let alone the entire perimeter of both, American troops would have had to move to given areas in response to threatening activities. The British on Defiance would have been able to note these deployments and inform their commander of the weakest areas. The eyes created yet another danger to the American positions. Coupled with the threat of incessant bombardment, the Americans had little choice but to leave.

[1]Many fault the American commanders for not constructing a defensive position on Mount Defiance. These accusers ignore the fact that neither the French nor the British in their earlier occupations of Ticonderoga bothered with putting anything up there. And, even if the Americans had built a fortification to protect that high ground, they did not have enough men to garrison it in 1777. They could not adequately defend the main works let alone an isolated outpost on Mount Defiance and would quickly have abandoned the position. The British army would have arrived to find a ready-made access road and fortification waiting for their immediate occupation.

[2]E-mail exchange with Stuart Lillie, Vice President of Public History, Fort Ticonderoga.

[3]The distances were determined by using the Ruler feature on Google Earth and the Interactive Map Viewer on the Vermont Center for Geographic Information website, maps.vermont.gov/vcgi/html5viewer/?viewer=vtmapviewer.

[4]John Trumbull, Sketch of the Life of John Trumbull, Written by Himself, 1835 (New Haven: B.L. Hamlin, 1841), 29-32.

[5]John Brown to unknown, October 4, 1777, “Col. John Brown’s Expedition Against Ticonderoga and Diamond Island, 1777,” The New England Historical and Genealogical Register vol. LXXIV (Oct., 1920), 293.

[6]Simon Fraser to John Robinson, July 13, 1777, “Gen. Fraser’s Account,” Proceedings of the Vermont Historical Society October 16 and November 7, 1900 (Burlington, VT: Vermont Historical Society, 1901), 144.

[7]Testimony of Henry Brockholst Livingston,Proceedings of a General Court-Martial . . . for the Trial of Major-General St. Clair, August 25, 1778 (Philadelphia: 1778), 37.

7 Comments

Good article Mike. Hopefully it will finally answer the question of Mt Defiance and the American abandonment of Fort Ti. However, these kinds of questions seem to persist even with the kind of hard evidence you have provided. We need more like this.

Mike;

Thanks for returning to a discussion of a recurring topic.

The Ft Ticonderoga spiel on this topic mistakenly attribute Trumbull’s artillery study to Benedict Arnold; it’s always good to see the facts cited.

Trumbull’s study is interesting, because it also proves that counter-battery fire from Ft Ticonderoga would have been effective against the British battery installed on Sugar Hill. With the ability to get large caliber ball the British guns were in equal jeopardy from Continental counter fire.

The fact has always indicated that the withdrawal was not about the threat of cannon fired from up above, but the ability of the British to count troops and determine troop dispositions. As you say, the American garrison at Ft Ti and Mt Independence had been reduced to a fraction of what it had been in the fall of ‘75. The garrison was significantly outnumbered by the the British force approaching on the Vermont side, as well as the force approaching through New York. Plus, with their command of the water, by destroying the bridge connecting Ticonderoga to Independence, the British could have isolated each then defeated them one at a time. Even today it’s near impossible to devise a winning strategy for the Americans; especially since all hope of reinforcement was foiled by Clinton’s preparations for a campaign in New York (which turned out to be the Philadelphia campaign).

Good timing for release of this article as we approach the anniversary of the conclusion of Burgoyne’s attempt to separate Bew England along the Hudson.

Warm Regards,

Jim

I’d be curious to see if Ti has some documentation for saying Arnold conducted the tests.

Sorry for the typos. Fat fingers, small phone.

‘75 should be ‘76. Might not be obvious to everyone. I’ll let you figure out the others. 😉

Mike, all future Saratoga campaign chroniclers should consult your article before describing the Ft. TI evacuation! Really thoughtful and interesting analysis.

It seems that the combined massive firepower of Burgoyne’s naval guns and seige artillery were more dangerous than a few guns on Mt Defiance. Likely, that’s why, even thought he fired the captured Mt Defiance guns, John Brown’s raid failed due to the lack of naval and seige artillery.

Funny that you mention Brown’s Raid: I am in the process of putting together an article on that very action. To briefly address your note (it’s a bit of a spoiler), Brown et al never intended to lay siege to Ti and/or Mt. Independence. More later.

Nice article, Mike. Another factor to consider in the evacuation of Mount Independence is the water supply along the (now) Blue Trail. St. Clair’s papers mention this water source and during the summer it may have been the primary source for water. I’m sure the British gunners would have noticed this and taken advantage of their abilities to zero in on target areas.

Paul Andriscin

Site Interpreter Mt. Independence Vermont Historic Site