When the vote came on Tuesday, July 26, 1781, before the House’s evening adjournment, it was Thomas Burke’s turn to hold the Executive office of North Carolina, beating out Samuel Johnson.[1] With the votes tallied, the legislature proclaimed to the Wake Court House in Raleigh that the, “the Honbl. Thomas Burke, Esquire” is requested in “attendance at the State House to qualify as Governor and have the Honors of Government conferred on him.”[2] As the legislature adjourned at 5 o’clock for dinner and an evening break, it dispatched a letter to inform Burke of the joint vote of both houses of North Carolina’s legislature. Just after dinner, Burke responded promptly from his temporary residence, writing, “I feel myself impressed with a deep sense of gratitude to the representative Body of my Country for this unexpected Honor and distinguished mark of their confidence.”[3]

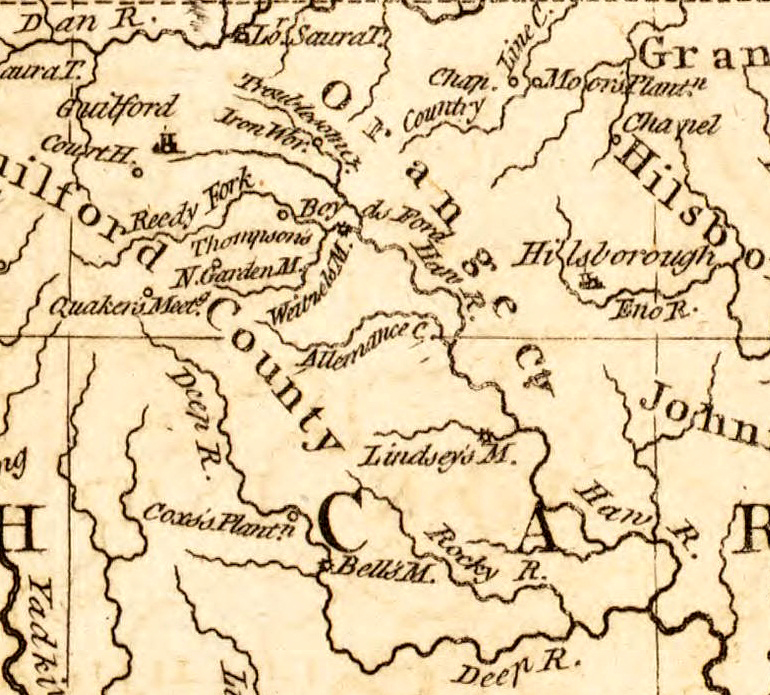

Born in Ireland, Burke was a well-educated doctor and lawyer who came to reside in Orange County, North Carolina, in the town of Hillsborough. Hillsborough’s central location in the colony, Burke’s educational depth, and the town’s nearness to the governing seat created avenues for Burke to grow in influence. A Patriot to the marrow, Burke received the privilege of serving in the Second Continental Congress from 1777-1781 alongside William Hooper and Joseph Hewes, both signers of the Declaration of Independence for North Carolina.[4] After resigning his seat in 1781, Thomas Burke became Patriot governor of North Carolina.

Burke came to the executive office after the dramatic events of Spring 1781. British Gen. Charles, Lord Cornwallis and Patriot Gen. Nathanael Greene had already clashed at Guilford Courthouse in March. Greene decided to press south into South Carolina, and Cornwallis pushed northward to offer further British support in Virginia. The war in North Carolina shifted back into the hands of factional militia leaders. Without the presence of larger armies, the war retained its neighbor-on-neighbor, civil war style character. One prominent commander of this style of fighting and factionalism was South Carolinian David Fanning.[5] On July 5, just weeks before Burke was elected governor, Fanning “was commissioned colonel of the loyal militia in Randolph and Chatham Counties by Major James Henry Craig, commanding at Wilmington.”[6] Fanning and Craig would work together intimately to disrupt the governance of Burke and North Carolina.

Disruption came first to the correspondence between Major Craig and Governor Burke. Burke no longer permitted Craig to write because of Craig’s refusal to honor “the condition of my [Craig] addressing him [Burke] as Governor of the Province.”[7] Burke would only receive and open letters addressed to him “as Governor” of the state.[8] To air this grievance over the exchange of correspondence, Craig was forced to write to William Hooper, who represented North Carolina in the Continental Congress. Beyond titles, frustration grew between the two parties over the harsh and punitive treatment of Tory and Whig prisoners. Tensions soon bubbled over into actions.

In the first week of September 1781, David Fanning was stationed at Camp Cox’s Mill. On the 6th he issued an advertisement to the region stating that “property would be seized” if men did not “repair immediately to camp.”[9] On the 9th, he received reinforcements from the surrounding areas, “Col’n McDugald of the Loyal Militia of Cumberland County, with 200 men, and Col. Hector McNeil, with his party from Bladen of 70 men; and in consequence of my advertisement I had also 435, who came in.”[10] Located just south of modern day High Point, North Carolina, Fanning had about 700 men at his disposal. Opposite Fanning was Patriot Gen. John Butler and Col. Robert Maybin of the Continental Line. Instead of attacking, Fanning and Craig had previously “determined . . . to take the Rebel Governor Burke of North Carolina.”[11] So Fanning, feinting toward General Butler, instead “pushed all day that day and the following night,” for it was some sixty miles to Hillsborough where Burke resided.[12]

Fanning’s men entered town at 7 in the morning of September 13. Governor Burke retrospectively called his capture an “unfortunate accident.”[13] It was more than an accident. A well-organized and armed Loyalist army initially “received several shots from different houses,” but soon “took upwards of two hundred prisoners, amongst them was the Governor, his council, and part of the Continental Colonels.”[14] It was not merely an accident, it was a blunder on the part the Governor Burke and General Butler. The swift capture turned into a quick flight. Knowing General Butler was nearby, Colonel Fanning quickly left Hillsborough at noon, “proceeded eighteen miles that night toward Cox’s Mill,” and the next day “eight miles further, to Lindley’s Mill on Cane Creek,” a tributary of the Haw River.[15] Treatment of the prisoners corresponded with these harsh marches away from the Patriot commanders.

Governor Burke had never been treated so poorly. In an October 17 letter, written from captivity in Wilmington, he attacked the treatment he received from Fanning and his men:

I will not trouble you with a relation of the different extremes of hunger, thirst and fatigue, and the frequent dangers ours lives were exposed to while we were in the savage hands of those who were our first Captors, who, to avoid the pursuit of our friends, traversed by long and rapid marches, vast pathless tracks of intermingled Sand and Swamp very thinly inhabited and which ought not to be inhabited at all, but will begin with our delivery into the hands of Major Craig on the 23rd of September at Livingston’s Creek on the North West of Cape Fear, by which time we were completely pillaged of every thing except the few dirty, worthless cloaths we had on, which, with regard to myself, were chiefly borrowed.[16]

Burke regarded his treatment as unbecoming of a prisoner of state. In Burke’s eyes, Fanning’s reputation as full of vice and without morals was well-earned. Burke would come to esteem Major Craig with a tailored perspective, while Fanning would receive the diligent eye of judgement for his morose conduct.

Arriving at Lindley’s Mill, or Cane Creek, on September 13, Fanning’s front guard was apathetic. They had “neglected to take the necessary precautions” and were fired upon before things could be corrected.[17] General Butler and his men had hidden themselves along the creek in a guerrilla-style ambush. Colonel McNiel had neglected to send forward moving troops to scout ahead. Butler’s men fired quickly, on a snap, and McNeil was shot through with several musket rounds.[18] Fanning too was hit, “in the left arm, which broke the bone in several places,” but only after having led his men forward, forcing them to wade the creek.[19] Loss of blood forced him to sit in a secluded place under a tree. He ordered Colonel McDugald to take command, and “to send to Wilmington for assistance.”[20] The Loyalist lost some twenty-seven men with sixty wounded.[21]

Butler pursued Fanning, forcing a hard march. The Patriots from Hillsboro marched in heavy pursuit for some 160 miles, but were turned back when Major Craig met the Loyalists with reinforcements. The prisoners’ transition to Wilmington was welcomed by Governor Burke, who recounted, “the British Officers behaved with frank politeness to us and Major Craig treated me with particular respect, in short, we had great reason to rejoice in our exchange of situation, and for the first time after our capture, felt ourselves out of danger of personal violence.”[22] But the governor was soon to learn that violence toward him was still possible. Other Patriot commanders did not feel as suddenly optimistic as Burke. Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene, commander of the southern Patriot forces, penned a concerned letter in which he stated,

I have this moment received the confirmation of the disagreeable report prevailing of Governor Burke and sundry other persons being taken near Hillsborough. I beg you [Gen. Sumner] will get yourself in readiness to go into that State as soon as possible as I fear all things will get into confusion from this untoward event.[23]

Something had to be done to free of Governor Burke and the other Patriot forces. It would, however, be some months before any opportunity arose. The first major word came from Burke on October 17, relating his position in a circular letter to North Carolinians.

It was yet undecided how prisoner Burke would be treated. Burke related to the inhabitants of North Carolina that he would either be “a prisoner of war or of State.”[24] The difference could mean either the dignity of the aristocracy or the degradation of a soldier. While his treatment was considered, Burke recounted his current situation in Wilmington:

He [Major Craig] conducted me to a house within the lines, one room whereof was assigned to be my place of confinement and for that purpose was shut up from all communication except by one door leading into the street, there he left me with a Sergeant to watch me constantly, and a Guard to prevent my escape and all access to me. This room is always dry in fair weather, and warm when the sun shines.[25]

As a prisoner of war, Burke was treated with far less dignity than he might have expected. He was permitted to request things of Major Craig, through application, yet “in every case wherein he could indulge me” he was, “with great respect & Politeness refused.”[26] Burke urged “to hasten my exchange.”[27] Exchange would not come quickly. Instead, Burke was moved from Wilmington to Fort Arbuthnot on Sullivan’s Island in South Carolina.

Conditions were worse, and moving to Sullivan’s Island was a shock. Burke arrived there on November 6 in an uncourageous spirit.[28] He soon dispatched two letters, on November 26-27, asking various Patriot officials to work for his exchange, offering them any help that could assist in his being cleared.[29] Fear arose because violence sometimes broke out in the fort, and Burke was afraid for his life. At one point, on November 29, “a party of the refugees fired on a small group who were at my Quarters and one man was killed on one hand of me and one wounded at a little distance on the other.”[30] The next day, on November 30, Burke wrote British commander Gen. Alexander Leslie, requesting a parole within the American lines and “informing you that my person was in great danger from the refugees.”[31] No word came in return. The winter months were chilly and dangerous. Burke began to consider designs to rescue himself. “When I had well weighed all these matters, I concluded myself perfectly released from the obligation of my parole as a Prisoner of War.”[32]

Finally, on January 16, Burke fled as his fear had escalated to “being thus in hourly danger of assassination.”[33] He informed General Leslie that he “saw no prospect of being delivered from my dangerous situation, and I concluded that such neglect of my personal safety would justify my withdrawing my person.”[34] Burke likely made his way through the waterways of Charlestown into the interior of South Carolina and into southern North Carolina. He eventually made his way into western North Carolina in the town of Salem, because on February 2, 1782 Governor Burke wrote for the General Assembly to meet in Salem on “Monday the 11th of this present month.”[35] Burke also attempted to console and negotiate with General Leslie. A prisoner of state was not expected to escape, instead honoring his terms of parole until released or exchanged. Burke knowingly broke the traditional protocol of the time. He tried to resolve the tension by telling General Leslie,“I will endeavor to procure for you a just and reasonable equivalent in exchange for me” or “I will return within your lines on parole” if “you will pledge your honor that I shall not be treated in any manner different from the officers of the Continental Army when prisoners of War.”[36] Lacking strong support from his state’s leadership, Burke negotiated from a weak position with little leverage and no strong advocates.

Although neither respected Burke, General Greene and General Leslie respected each other. They corresponded regarding Burke’s flight with cordial respect and dignity becoming their offices. On January 27, Leslie wrote to Greene, assuring him that he did not think Burke absconded on Greene’s advice. He called out Burke as a “person acting so contrary to the character of a gentleman.”[37] Leslie was so incensed by Burke’s actions that he directed Greene to “immediately order him to return and deliver himself up to the Commissary of prisoners in Charlestown.”[38]

Greene responded promptly and with the same respect, but expressed concern for the state of prisoners on Sullivan’s Island. Greene could not “justify the violation of a parole,” but also was “not agreed with you in opinion that his [Burke’s] apprehensions were chimerical.”[39] He felt some sense of the dangers of British imprisonment, adding the desire “to know in what light you consider him, whether a prisoner of War, or . . . State.”[40] The type of prisoner would determine the level of exchange. William Davie, a promient and ardently Patriot North Carolina milita commander, asserted “that it was the opinion of the Court and General Greene that the Enemy have legal claim upon you [Burke] as a prisoner of War.”[41] This must have sent a shudder down Burke’s spine. With that, on February 5, Greene wrote to Burke enclosing the discourse between himself and General Leslie. Insisting upon a response, he informed Burke, “Gen’l Leslie has demanded your immediate return.”[42] He nonetheless planned to exchange him and other prisoners if that was agreeable. If an exchange occurred, Burke would not have to go back to the horrid existence on Sullivan’s Island.

The General Assembly did not meet in Salem, showing some passive disdain for the governor. Instead, Burke was forced to call another meeting in Hillsborough on Tuesday, April 2, 1782.[43] Not owing to the authority of Governor Burke, the assembly met from mid-April to mid-May. On April 16, the first major act it took on was the issue of Governor Burke. The governor-turned-absconded-fugitive was a shameful stain on the dignity of the North Carolina gentry. Burke knew that the issue needed to be resolved, so he dispatched a letter to the General Assembly; to attend in person would be in bad taste. After qualifying his behavior and recounting the already well-known story, he was pointed. He explained fully to the Assembly that,

The nearer I approached home and the more information I received, the more I was induced to decline forever all public business and I expected to find the General Assembly convened at Salem and into their hands to resign the Trust with which they had invested in me . . . The Speaker of the Senate suggested to me that this office would expire on the next General election and apprehending that great confusion might arise and much injury to the public especially while preparations were making for a vigorous campaign and the country still remained infested with internal enemies, I conceived that I could not be justifiable in declining to discharge my duty unless I was disqualified.[44]

Burke resigned. Not only did his poor, absent leadership leave the state in confusion, but he was not seen by the Speaker of the Senate as someone worthy of the dignity of the office. The General Assembly was ashamed of the governor’s actions. He had not acted as a prisoner of state, he had acted as a prisoner of war, precisely the thing he did not want to be during his imprisonment. A false modesty seeped through his final remarks, as Burke contended for the assembly’s sympathies: “I hope I shall be permitted to return to a more private life which is so necessary to my affairs.”[45] Burke retired for a year to the comfort of his Hillsborough estate, and just one year later, on December 2, 1783, the “poor Doctor Burke” was “no more.”[46] It was, as one North Carolinian put it, “a heavy loss to the public at this time, notwithstanding his failings and peculiarities.”[47]

Despite serving in the Continental Congress and having Burke county named after him, Thomas Burke is not well known for his contributions to Revolutionary North Carolina. His capture demonstrates the Revolution’s grimy nature in the Southern Colonies. Colonel Fanning’s seizure of Governor Burke exposed his lack of ability to lead in the executive office. Burke was shown to be uncourageous, self-centeredly aristocratic, and, despite his education, un-prepared to lead in a time of war or peace. Despite these failings, Burke should not be forgotten. He represents the tumultuous time of the Revolutionary period in the Carolinas.

[1]“Minutes of the North Carolina, General Assembly, June 23, 1781-July 14, 1781,”Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, Documenting the American South, docsouth.unc.edu/csr/, 17: 803 (CSR).

[4]“Minutes of the Continental Congress, February 4, 1776” CSR, 11: 705.

[5]Ian Saberton, “Biographical Sketches of Royal Militia Commanders in the South Carolina Mid- and Lowcountry, North Carolina, and Georgia, 1780–82,” Journal of the American Revolution,November 28, 2020, allthingsliberty.com/2020/12/biographical-sketches-of-royal-militia-commanders-in-the-south-carolina-mid and-lowcountry-north-carolina-and-georgia-1780-82/.

[7]James Craig to William Hooper, July 20, 1781, CSR, 15: 553-555.

[8]Thomas Burke to Craig, June 27, 1781, CSR, 22: 1026-1029.

[9]“Memoir ‘Narrative of the Life of Colonel David Fanning’ concerning the Revolutionary War,” CSR, 22: 206.

[13]“Letter from Thomas Burke, October 17, 1781,” CSR, 15: 650-654.

[14]“Memoir ‘Narrative of the Life of Colonel David Fanning’ concerning the Revolutionary War,” CSR, 22: 207.

[16]“Letter from Thomas Burke, October 17, 1781,” CSR, 15: 650-654.

[18]“Memoir ‘Narrative of the Life of Colonel David Fanning’ concerning the Revolutionary War,” CSR, 22: 207.

[22]“Letter from Thomas Burke, October 17, 1781,” CSR, 15: 650-654.

[23]Nathanael Greene to Jethro Sumner, September 25, 1781,” CSR, 15: 644.

[24]“Letter from Thomas Burke, October 17, 1781,” CSR, 15: 650-654.

[28]Burke to Greene, January 19, 1782, CSR, 16: 184-186.

[29]Burke to Alexander Martin, November 26, 1781, CSR, 22: 200-201. Burke Lewis Henry De Rosset, November 27, 1781, CSR, 15: 667-669.

[30]“Minutes of the North Carolina House of Commons, April 16, 1782 – May 18, 1782,” CSR, 16: 16-19.

[31]Burke to Alexander Leslie, January 18, 1782, CSR, 16: 178.

[32]“Minutes of the North Carolina House of Commons, April 16, 1782 – May 18, 1782,” CSR, 16: 16-19.

[33]Burke to Greene, January 19, 1782, CSR,16: 184-185.

[34]Burke to Leslie, January 18, 1782, CSR,16: 178.

[35]“Circular Letter from Thomas Burke to the Members of the North Carolina Council of State, February 2, 1782,” CSR, 16: 181.

[36]Burke to Leslie, January 18, 1782, CSR,16: 178.

[37]Leslie to Greene, January 27, 1781, CSR, 16: 179.

[39]Greene to Leslie, February 1, 1782, CSR, 16: 179-180.

[41]William Richardson Davie to Thomas Burke, February 23, 1782, CSR, 16: 202.

[42]Greene to Burke, February 5, 1782, CSR, 16: 186.

[43]“Proclamation by Thomas Burke Concerning the Meeting of the North Carolina General Assembly, 1782,” CSR, 15: 712.

[44]“Minutes of the North Carolina House of Commons, April 16, 1782 – May 18, 1782,” CSR, 16: 18.

[46]Archibald Maclaine to Hooper, December 23, 1783 – December 28, 1783, CSR, 16: 999.

Recent Articles

Revolution Road! JAR and Trucking Radio Legend Dave Nemo

Those Deceitful Sages: Pope Pius VI, Rome, and the American Revolution

Trojan Horse on the Water: The 1782 Attack on Beaufort, North Carolina

Recent Comments

"Texas and the American..."

Mr. Villarreal I would like to talk to you about Tejanos who...

"Trojan Horse on the..."

Thank you Eric! I should say that I have enjoyed your work...

"Trojan Horse on the..."

Great article. Love those events that mattered mightily to participants but often...