‘Tis to ye Press & Pen we Mortals owe

All we believe & almost all we know:

—George Fischer, The American Instructor: or, Young Man’s Best Companion, 1770

The Press was the media that shaped the political process of the American Revolution. Colonial newspaper publishers generally produced four-page weeklies and/or single-sheet broadsides to keep colonists informed of local events and of happenings hundreds of miles away. They also printed pamphlets to convey political philosophies and possibilities. Often written by elites under pseudonyms, some pamphlets attempted to rouse colonial resistance by framing dissension with references to historical political upheavals.

There were no reporters as such, so some stories were “borrowed” (plagiarized) from papers located in other cities. This reportage uniformity, analogous to the modern news wire, allowed stories to appear across North America and provide the Revolutionaries a conduit to reinforce a fragile sense of unity. Newspapers and broadsides helped drive American resistance to the British and publishers on both sides were not obliged to print opposing viewpoints.

‘Tis truth (with the difference to the college)

News-papers are the spring of knowledge,

The general source through the nation,

Of every modern conversation.

What would this mighty people do,

If there, alas! were nothing new?

A news-paper is like a feast,

Some dish there is for every guest;

Some large, some small, some strong, some tender,

For every stomach, stout or slender.[1]

Colonial newspapers printed accounts of the proceedings of Provincial Assemblies and Congress, official governmental reports and proclamations, plus news concerning the progress of the Revolutionary War’s campaigns. Vitriol and frequently scathing language awakened the consciousness. It led to a common purpose and destiny among politically disparate colonies while discouraging civic indifference and arousing public support for a successful conclusion of the war. An American physician suggested that print media played a vital role in the quest for self-determination. He wrote, “In establishing American independence, the pen and the press had a merit equal to that of the sword.”[2]

The number of North American newspapers published from 1775 to 1781 varied over time and location.[3] Roughly fourteen were in New England while twenty-four were in circulation farther south. War-related economic hardships caused seventeen papers that existed before the conflict to fail.[4] During the Revolutionary War newspapers became more objective or less provocative, perhaps no longer seeing the need to loudly laud the ideals of liberty and brashly damn the King, but publishers believed that their readers would be best served by being told precisely how the struggles were going, largely in blunt terms. There were thirty-seven active newspapers in the colonies when Cornwallis surrendered in October 1781, but by 1783 there were only twelve in New England and thirteen in the middle and southern states.[5]

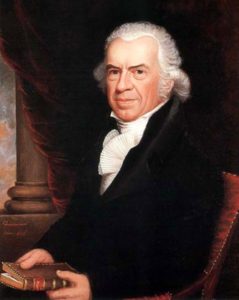

The leading printer’s business editor, Bostonian Isaiah Thomas, emerged as one of the most important and respected journalists of the revolutionary period. He entered the workshop as a small boy to stand on a stool and set type as an apprentice under Zechariah Fowles. “Thomas [received] his education from setting type and reading galley proofs, and . . . living with books all his life.”[6] Thomas learned from borrowed books, reading them well into the night and memorizing long passages in a variety of disciplines. He emerged as one of the finest scholars in America and by the time of his death possessed one of its best private libraries, becoming a founder and the first president of the American Antiquarian Society.

Although legally bound to Mr. Fowles, when he turned sixteen he ran away from Boston and took refuge in Nova Scotia. Thomas found employment at the Halifax Gazette and was allowed relatively free rein—for a while. The teenaged renegade Yankee made his position known from the first issue he produced saying that the British had shown themselves to be miscreants in virtually all of their governing with regard to the American colonies. They were expressly to blame for the insensitivity and excesses of the Stamp Act. Thomas attempted to be less vitriolic, but repeated the charges in several more issues. The newspaper’s owner had no choice but to fire Thomas, causing the rejected printer to returned to Boston.

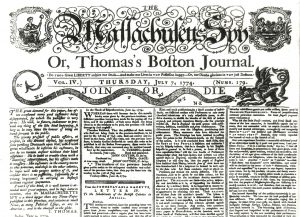

Young Isaiah Thomas became a newspaper publisher at the age of twenty-one, producing the first issue of the Massachusetts Spy in 1770. In an ironic move, he partnered with his former master Zechariah Fowles for financial help. The Massachusetts Spy was written for the semi-literate citizenry, the tabloid of the day. For a short time, Thomas would later also produce Royal American Magazine, the Royal in its title designed to attract a more refined audience of local highbrows or the literati, but it lasted only six issues and was sold to Joseph Greenleaf. One historian noted that “Thomas would be America’s first great printer, great publisher. . . . He had a sure publisher’s instinct for the time and place and the reading matter.”[7] Between 1771 and 1775 his printing press was located on Union Street in Boston. Sons of Liberty and fellow Masons including John Hancock, James Otis, and Paul Revere drafted some insurrection plans in his print shop.

The Massachusetts Spy became very successful and the former apprentice was able to buy out Fowles. He also gained the respect of his political opposite, Tory publisher James Rivington, who noted that “few men, perhaps, were better than Thomas to publish a newspaper. No newspaper in the colonies was better printed or more copiously furnished with foreign intelligence.”[8] Rivington did not approve of Thomas’s politics. He noted that Thomas had appropriated the Pennsylvania Gazette’s provoking segmented snake cartoon and reprinted it under the paper’s masthead as a means of urging the colonies to stand together against the King in the plea “Join or Die.” Rivington countered with the following serpent-like retort:

YE Sons of Sedition, how comes it to pass,

That America’s typ’d by a SNAKE—in the grass?

Don’t you think “tis a scandalous, saucy reflection,

That merits the soundest, severest Correction,

NEW-ENGLAND’s the Head too; —NEW ENGLAND’s abuse;

For the Head of the serpent we know should be Bruised.[9]

Most newspaper publishers, then as now, stayed in the background relying on others for news delivered to them as written stories, some occasionally whispered or anonymous notes slipped under the door. The British threated to hang Thomas so two nights before the battle of Lexington, he fled Boston. An overriding concern was that Thomas could be imprisoned and The Spy closed down by the crown’s authority that had sanctioned it several times in the city.

Thomas’s character included pugnacity as well as curiosity. He liked being close to action. On April 20, 1775 he traveled to Lexington and wrote about the aftermath of the carnage that he observed, arguably becoming America’s first war correspondent.

AMERICANS! Forever bear in mind the BATTLE of LEXINGTON! where British Troops, unmolested and unprovoked wantonly, and in a most inhuman manner fired upon and killed a number of our countrymen, then robbed them of their provisions, ransacked, plundered and burnt their houses! nor could the tears of defenseless women, some of whom were in the pains of childbirth, the cries of helpless, babes, nor the prayers of old age, confined to beds of sickness, appease their thirst for blood!—or divert them from the DESIGN of MURDER and ROBBERY![10]

This opening paragraph was “The Shot Spread ’Cross the Page.”[11] Reported by Thomas, it appeared in the May 3, 1775 edition of Massachusetts Spy. After that the article shifted from an agitator to relative neutrality, giving information about troop dispositions and ground gained and lost from reports of individual militiamen. The article ended with the perchance biased observation, “We have the pleasure to say that notwithstanding the big provocations given by the enemy, not one instance of cruelty we have heard of was committed by our Militia.”[12]

Shortly thereafter Thomas wrote in what became the Massachusetts Spy Or, American Oral Liberty that the British Parliament was “the most sanguinary and despotic court that ever disgraced a free country,” the King and his ministers “the most profligate in abandoned administration,” and the British citizens “a venal and corrupt majority.”[13] He sounded the alarm to his readers that became a classic cry, “Americans!—Liberty or Death!—Join or Die!”[14] The metaphorical snake must not remain severed.

Concerned that the British military garrison in Boston might destroy his business and livelihood, he permanently moved his operation to Worcester, roughly fifty rutted road miles away from the city that had been his home base. He had more freedom of the press, but became more cautious in his actions and words until the British evacuation of Boston on March 17, 1776.Reestablishing his enterprise in Worcester, Isaiah Thomas published his newspaper, printed and sold books, and built a paper mill and bindery.

Editor Thomas now published another similar newspaper, TheWorcester Spy. Its primary audience was the middle class—Thomas wanted his message to resonate with the common man, his original intention when he established The Massachusetts Spy back in 1770.The impact of The Worcester Spy was unmatched in America. During the Revolutionary War it was the most popular newspaper in the America. As a business The Worcester Spy achieved a circulation of about 3,500, ran sixteen printing presses, and had 150 employees at its height—roughly seven times any average newspaper in print at the time.The paper ran until 1802 except for a few gaps in 1776–1778 and after the Revolutionary War in 1786–1788.

The press, led by people like Isaiah Thomas, was instrumental in fulminating the revolution and chronicling its bumpy progress. The print media continued its role after the war with fervor and perhaps even greater rancor, but for entirely different reasons—to influence emergent policies in the nascent self-reliant American government.

[1]New York Gazette, or, The Weekly Post-Boy, April 16, 1770.

[2]David Ramsey, The History of the American Revolution, Volumes I and II (Indianapolis, IN: Liberty Fund, 1900), “In establishment of American Independence,” 634.

[3]Eric Burns, Infamous Scribblers, The founding Father and the Rowdy Beginnings of American Journalism (New York, NY: Public Affairs, 2006), 183.

[5]Robert G. Parkinson, Print, the Press and the American Revolution, doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.013.9.

[6]John Tebbels. The Compact History of the American Newspaper (New York, NY: Hawthorn Books, 1969), 39.

[7]Esther Forbes, Paul Revere and the World He Lived In (New York, NY: The American Past, Book-of-the-Month Club, inc, 1983), 205.

[8]John Tebbels and Sarah Miles Watts, The Press and the Presidency: from George Washington to Ronald Regean (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1985), 8.

[9]Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer, August 15, 1774.

[10]Massachusetts Spy, May 3, 1775.

[11]Eric Burns, Infamous Scribblers, 185.

Recent Articles

The 1779 Invasion of Iroquoia: Scorched Earth as Described by Continental Soldiers

That Audacious Paper: Jonathan Lind and Thomas Hutchinson Answer the Declaration of Independence

Supplying the Means: The Role of Robert Morris in the Yorktown Campaign

Recent Comments

"Eleven Patriot Company Commanders..."

Was William Harris of Culpeper in the Battle of Great Bridge?

"The House at Penny..."

This is very interesting, Katie. I wasn't aware of any skirmishes in...

"Texas and the American..."

Mr. Villarreal I would like to talk to you about Tejanos who...