Written human history only dates back a few thousand years while geologic time is often measured in tens or hundreds of millions of years. While social sciences often consider the physical geography of the environment where people live, geology often plays an equally important role. Understanding the geology of Yorktown, Virginia, and the surrounding area provides context for historians to better understand the physical geography and the military events of 1781 and beyond. Yorktown was the site of two sieges, the 1781 Revolutionary War siege, the primary focus of the Colonial Historic Park interpretative activities there, and the 1862 siege during the American Civil War. Both occurred because of the unique terrain and geologic conditions in and around Yorktown that continue to influence the human behavior involving economic and military development of the region. Using modern military terminology, Yorktown, Virginia, and the surrounding area including the York River, James River, Hampton Roads, and the Chesapeake Bay, were “key terrain” and potential “decisive points” in two very important military campaigns. The conditions there also facilitated military operations during World War I and continue to hold military significance well into the twenty-first century.

Contemporary military terminology defines key terrain as “any locality, or area, the seizure or retention of which affords a marked advantage to either combatant,” while a decisive point is “a geographic place, specific key event, critical factor, or function that, when acted upon, allows commanders to gain a marked advantage over an enemy or contribute materially to achieving success.”[1] Because of the unique physical features of Yorktown and the adjacent waterways, leaders and decision makers recognized their military importance and leveraged their value in execution of military operations.

But why did Yorktown offer a suitable anchorage surrounded by relatively high, dry, and defendable ground when most of the topography in the lower portions of the Chesapeake Bay offers little or no high ground and few naturally occurring, suitable and defensible deep-water anchorages? Why did Yorktown and the York-James Peninsula contain these physical attributes? What made Yorktown attractive was the unique geology and hydrography of the location.[2] As twentieth-century scientists studied the geology and hydrography of the lower Chesapeake Bay, they discovered something quite remarkable that contributed significantly to Yorktown gaining the distinction as the site of the last major North American campaign of the American Revolution.

Geology

While the military history that brought Lord Cornwallis to Yorktown may have begun with Cornwallis’s desire to escape the irregular war in the Carolinas,[3] or the instructions of Sir Henry Clinton and Lord George Germain, a long and lengthy geologic timeline created the physical environment that drew human settlement to Yorktown. In-depth scientific discovery of the region revealed a meteor strike approximately thirty-five million years ago. Scientists began serious study of the unique geologic and hydrographic characteristics of the lower Chesapeake Bay by analyzing anomalies in ground water in the local acquirers.[4] By the 1980s, 200 years after Yorktown served as the site of a major British military defeat, scientists formally published research supporting the strike of a large meteor.

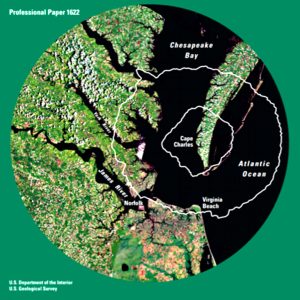

The meteor was massive, currently evaluated as the tenth largest known to have struck the earth.[5] Centered near the town of Cape Charles, Virginia, near the tip of the Delmarva Peninsula, the crater, identified by the extensive fractures of rock and disturbed soil layers, extends over six miles into the crust of the earth. The impact created a crater fifty-six miles across, producing a “complex peak-rim.” Yorktown is situated on the western side, perched on a surviving portion of the rim of the thirty-five-million-year-old crater. At the time of the meteor strike, the area around Yorktown was under about 100 feet of water and the coastline located in the vicinity of Richmond, Virginia.[6]

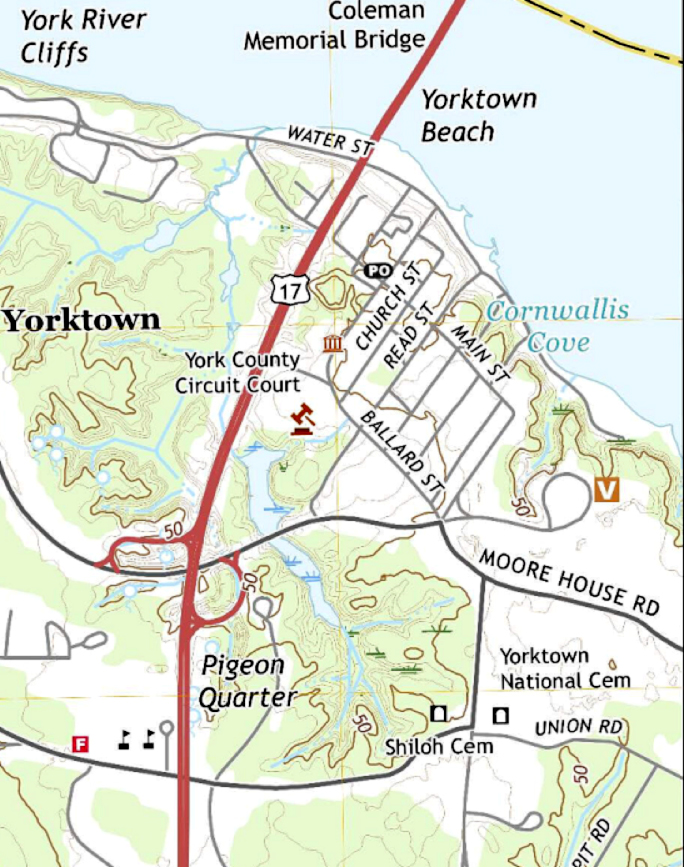

The Appalachian Mountains formed over 400 million years ago and gradually eroded to form the Coastal Plain.[7] Rivers originating in the Appalachian Mountains and Piedmont cut their way to the Coastal Plain, sculpting the landscape. The York River cut through sediment and debris created by the meteor strike resulting today in a deep channel, extending sixty feet below modern sea level and the adjacent terrain rising fifty or more feet above the York River as it joins the Chesapeake Bay.[8]

Yorktown and the Military

General Charles Cornwallis moved the British main operating base in the Chesapeake Bay from Portsmouth to Yorktown, Virginia, during the summer of 1781. The reasons for this move are well documented in the surviving correspondence between Lord Cornwallis and Sir Henry Clinton.[9] For a successful and sustainable occupation of the Chesapeake Bay, the British Navy needed an advanced naval base and anchorage, a deep-water port capable of accommodating the deep-draft ocean-going ships of the line mounting more than sixty-four cannons and drawing over twenty feet of water. In addition to providing a deep-water port, Yorktown provide high, well-drained ground, necessary for a healthier environment for the troops.

During the Yorktown Campaign of 1781, control of the Chesapeake Bay was a decisive point while Yorktown represented key terrain. A sustainable British naval presence in the bay offered the opportunity to choke Whig commerce on a waterway that carried forty percent of the pre-war commerce and remained an important water highway for the Whigs throughout the war. The coastal river system also allowed for relatively secure and reliable movement of troops and supplies in shallower-draft vessels as far inland as the fall line, providing access to the towns of Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Alexandria. Numerous plantations lined the banks of the rivers and bay. These factors contributed to Virginia having the largest population of the original thirteen states yet no large cities because of the agriculturally-based economy that exported primarily food stuffs and raw material.[10]

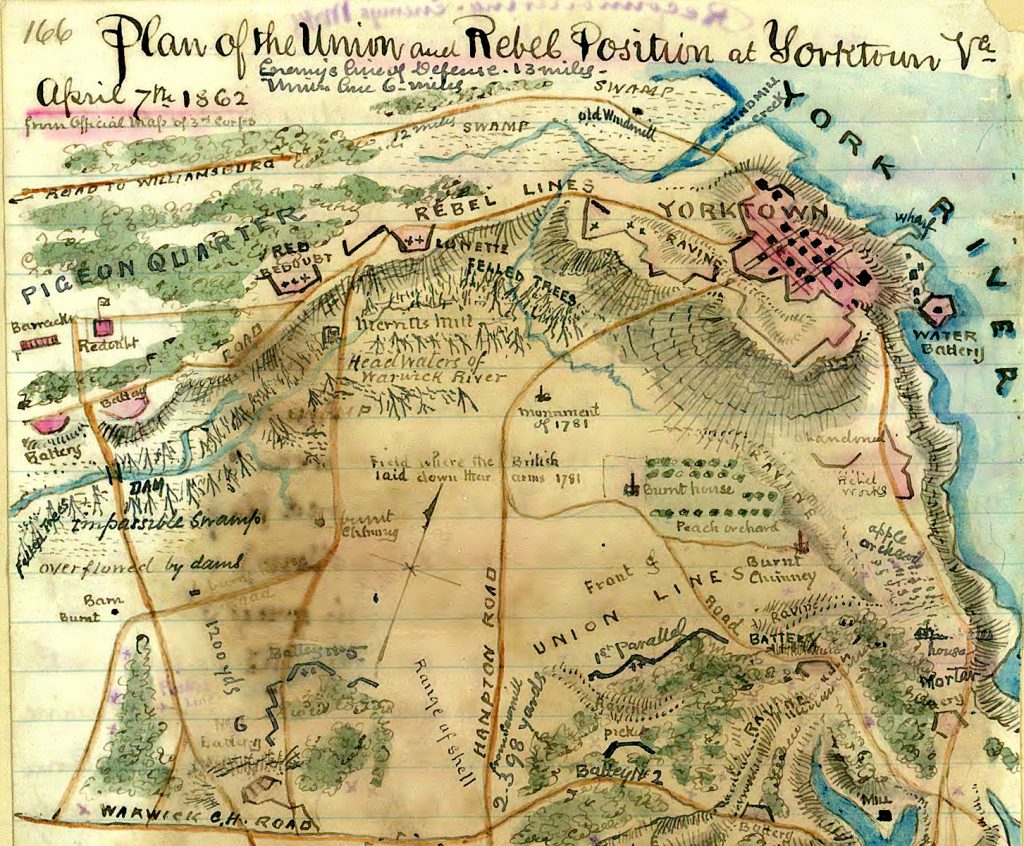

During the Civil War the Union Army, under command of Gen. George B. McClellan, executed a campaign involving over 100,000 soldiers using the Virginia Peninsula, the land between the James and York Rivers, as an avenue of approach to the capitol of the Confederacy, Richmond, Virginia. The plan required a buildup of Union forces at Fort Monroe (Old Point Comfort) and capitalized on the movement and sustainment of forces using the surrounding navigable waterways. The Confederate forces under command of Gen. J.B. Magruder countered with construction of a defensive line anchored on the key terrain of Yorktown, the high ground suited for maneuver of large numbers of troops, on the eastern end of their twelve-mile-long defensive line. This set the stage once again for a climactic siege at Yorktown because the Confederate defenses extended to the south and west along the Warwick River. Portions of the low terrain along the Warwick River were flooded and not well-suited to a large Union attack, and therefore were more easily defended with fewer forces. Ultimately, Confederate forces withdrew from the line before the Union assault but delayed the attacking forces for over a month, providing time to build additional defenses and slow and ultimately stop the Union attack closer to Richmond.[11]

Fifty years after the American Civil War, the U.S. confronted another global conflict, World War I. As the character of war evolved in response to changing technology, Yorktown once again served in another important role linked to the same geology that made the region attractive during previous conflicts. During 1917, with the advent of submarine warfare by the Germans, the U.S. Navy took unprecedented action to provide safe harbor, placing the Atlantic Fleet behind a submarine net stretched across the mouth of the York River. The German submarine threat prompted the U.S. Navy to adopt a defensive force protection posture and the York River at Yorktown provided a safe and secure anchorage from this new threat.[12]

The emergence of the submarine threat ultimately resulted in Yorktown serving another key role as a mine warfare depot. In response to the devastating impact of German submarine warfare, the U.S. Navy seized the property upstream from Yorktown on the south bank of the York River and created a mine warfare depot. The site was close to the Norfolk Navy Yard and the Norfolk Operating Base. Serviced by rail lines and with the advocacy of the Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Yorktown quickly became the world’s largest naval base. A local newspaper carried an article on August 21, 1918 titled, “Yorktown Harbor to be Used as Great Naval Base.” Today, Yorktown continues to serve as the principal weapons storage facility on the east coast for the U.S. Navy. If you visit Yorktown today you may be fortunate enough to see a U.S. Navy warship transiting to or from the weapons station to onload or offload munitions prior to or after deployment or for training.[13]

Conclusion

The next time you visit Yorktown, or any other revolutionary era site, consider why the military or political events we study occurred there. In most cases the military events associated with that location tie back to the physical geography that drew people there and resulted in human and economic development; these conditions often tie back to geology. A study of these factors will ultimately lead to linkages to enduring ideas framed in the contemporary military terminology including concepts like key terrain or decisive points. Yorktown is a unique area in the lower Chesapeake Bay because it possesses the physical qualities that resulted in General Cornwallis moving his base of operations in the Chesapeake Bay there in 1781. While the human decision-making process determined the military actions in moving forces there, the physical geography and geology and subsequent human development of the region set the conditions that that drew the British Army there in 1781. These conditions link directly to millions of years of geologic evolution and in the case of Yorktown, the remnants of a thirty-five-million-year-old crater. An appreciation of these factors helps explain the prominent role Yorktown played during the American Revolution and the influence geology continues to exert on Yorktown and the region.[14]

[1]Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, DoD Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, 2020), 58, 125, www.jcs.mil/Portals/36/Documents/Doctrine/pubs/dictionary.pdf.

[2]As technology advanced the range and lethality of military weapons systems, the standoff distance increased rendering the point defense more of a tactical rather than a strategic or operational consideration. However, key anchorages, harbors and maritime choke points remain major considerations in force posturing and military operations around the globe.

[3]Ian Saberton, Why was the Revolutionary War in the South Lost by the British? Journal of the American Revolution, September 28, 2020, allthingsliberty.com/2016/09/why-revolutionary-war-south-lost-british/. Saberton introduces an interesting thesis on why Cornwallis abandoned the Carolinas in favor of Virginia: “a humane, cultivated man, he was sickened by the murderous barbarity with which the war was waged there by the revolutionary irregulars and state troops; he had no stomach for the deterrent and necessarily disagreeable measures involved in suppressing the rebellion there; and he was suffering from the mental and physical fatigue of commanding a year’s hard and solid campaigning.” However, one must also consider that the Virginia campaign unleashed similar events in Virginia because the British Army did not possess the necessary strength to seize and hold the state or liberate the Loyalists or restore Royal governance. The British Army’s presence in Virginia produced the retribution associated with vengeful acts common in civil wars, what Cornwallis was trying to leave behind in the Carolinas. For an example see, Karl Gustaf Tornquist and Amandus Johnson, The Naval Campaigns of Count de Grasse During the American Revolution (Philadelphia: Swedish Colonial Society, 1942), 57-8.

[4]David. S. Powars and T. Scott Bruce, U.S. Geologic Survey Professional Paper 1612, Effects of the Chesapeake Bay Impact Crater on the Geologic Framework and Correlations of Hydrogeologic Units of the Lower York-James Peninsula, Virginia(Washington: US Government Printing Office, 1999), 1, 7, pubs.usgs.gov/pp/1612/report.pdf.

[5]Brett Line, “Asteroid Impacts: 10 Biggest Known Hits,” National Geographic News, February 15, 2013, www.nationalgeographic.com/news/2013/2/130214-biggest-asteroid-impacts-meteorites-space-2012da14/.

[6]Powars and Bruce, Effects of the Chesapeake Bay Impact Crater, 7, 11.

[7]Phil Berarelldi, “The Mountains that Froze the World,” Science Now, November 3, 2009, news.sciencemag.org/sciencenow/2009/11/03-02.html?eto.

[8]Carl T. Friedrichs, “York River Physical Oceanography and Sediment Transport,” Journal of Coastal Research, SI, 57 (Gloucester Point, VA: Virginia Institute of Marine Science, 2009), 17-22, www.vims.edu/cbnerr/_docs/site_profiles/Friedrichs_%20Phys_Oceangphy.pdf.

[9]Ian Saberton, ed., The Cornwallis Papers(Uckfield: The Naval & Military Press Ltd., 2010), Clinton to Cornwallis, July 11, 1781, 5: 139; Clinton to Cornwallis, July 11, 1781, 5: 142-3; Graves to Cornwallis, July 12, 1781, 5: 145-6; Germain to Cornwallis, April 4, 1781, 5: 151; Cornwallis to Leslie, July 20, 1781, 5: 195; Extracts from the Philips Papers, March 10, April 26, June 11, 1781, 6: 15-6; Engineer’s Report 25 July, 1781, 6: 16-17; Naval Report, July 26, 1781, 6: 17-18; Clinton to Cornwallis, August 11, 1781, 6: 23-4; Cornwallis to Clinton, August 16, 1781, 6: 24-5; Cornwallis to Clinton, August 16, 1781, 6: 24-5; Cornwallis to Clinton, August 20, 1781, 6: 25-7; and Cornwallis to Clinton, August 22, 1781, 6: 27-29;and Ian Saberton, The Aborted Virginia Campaign and Its Aftermath, May to August 1781, Journal of the American Revolution, November 23, 2020, allthingsliberty.com/2020/11/the-aborted-virginia-campaign-and-its-aftermath-may-to-august-1781/.

[10]Ernest McNeill Eller, ed., Chesapeake Bay in the American Revolution(Centerville, MD: Tidewater Publishers, 1981), 14, 16; John E. Selby, The Revolution in Virginia, 1775-1783(Charlottesville, VA: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1988), 26; Everts B. Greene and Virginia D. Harrington, American Population Before the Federal Census of 1790(Glouchester, MA: Peter Smith, 1966), 7-8, 141; and Robert K. Wright, The Continental Army(Washington, DC: Center for Military History, 1983), 93. Because of the lack of large population centers, based in part on the geography and geology of Virginia, the successful return of Virginia to Royal governance was beyond the capacity of Cornwallis’s Army of 7,200 soldiers and 800 sailors that he surrendered at Yorktown. Virginia’s population was about 600,000.

[11]National Park Service, Yorktown in the Civil War, www.nps.gov/york/learn/historyculture/yorktown-in-the-civil-war.htm.

[12]Mark St. John, “Giant Mine Depot in Yorktown Spurred by WW I U-Boat Menace, Hampton Roads History,” The Daily Press, August 4, 2018, www.dailypress.com/history/dp-nws-wwi-yorktown-mine-depot-20180730-story.html.

[13]Commander, Navy Region Mid-Atlantic, Naval Weapons Station Yorktown, Welcome to Naval Weapons Station Yorktown,www.cnic.navy.mil/regions/cnrma/installations/nws_yorktown.html and, St. John, “Giant Mine Depot.”

[14]ODU News, “Report: Economy in Hampton Roads will continue to grow in 2020,” Williamsburg Yorktown Daily, February 18, 2020, wydaily.com/local-news/2020/02/18/report-economy-in-hampton-roads-will-continue-to-grow-in-2020/. Approximately 40 percent of the annual economic activity in the southeastern Virginia region is attributed to the military.

5 Comments

Pat – Very interesting new view of an old topic. I enjoyed it and learned much. Is the Civil War era map by Sneden? Thanks. Not bad for a retired Marine.

Bill

Bill, Thanks. The Civil War Map is from the Library of Congress. There are several available, Sneden, Robert Knox is credited as the contributor. In ground combat the last 10 yards is the most difficult terrain on the battlefield. The Marine Corps does a good job of educating one on this fact. One gets lots of practice in the school of hard knocks. Pat

Patrick:

Thanks for this excellent article. Geology and its influence on campaigns and battles is a subject which is always interesting and doesn’t get enough attention. One thing the USGS paper doesn’t address (because it is only peripheral at best to the subject) is soil conditions at Yorktown. Further up the Peninsula those conditions, especially given the prevalence of ultisols, had a substantial effect on military operations during the wet Spring/early Summer of 1862. Any idea what the soils at Yorktown are?

John, Thanks. The soil around Yorktown is very sandy and drains better than most soils in the area. Ultisols appear to have a higher clay content. Take a look that this 1905 document, https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_MANUSCRIPTS/virginia/yorktownVA1905/yorktownVA1905.pdf (page 252 states “unconsolidated fine sands and sandy clay.” When you walk between the British earthworks and the Moore House Road you really notice the sandy soil. Take a walk between the British Hornwork, Redoubt Number 9 and the Moore House Road. You will find numerous cacti, indicating it drains well, a rare find in this part of the world; watch your step. Just another unique aspect of Yorktown.

Patrick: Thanks for the information. The clay content of the ultisols was a big part of the problem with roads in 1862, especially in the Seven Pines/Fair Oaks area. Since the Federals moved and placed big guns in the Yorktown/Warwick line area in April 1862, I was wondering about the issue in that location.