During the Revolutionary War, the British were particularly sensitive to challenges to their maritime sovereignty. Members of the Continental Navy, states’ navy sailors or letter of marque privateers, when taken prisoner, were usually interned onboard prison hulks moored in Wallabout Bay in New York harbor. Seamen captured far from North American shores were often incarcerated in naval prisons where many tried imaginative schemes to escape. Some succeeded, most were recaptured and faced dire consequences, but a fortunate few were freed in prisoner exchanges. The following three accounts provide a glimpse of those times.

Nathaniel Fanning

On May 26, 1778, at the age of twenty-three, Nathaniel Fanning signed on the privateer brig Angelica. She mounted sixteen guns and carried ninety-eight men and boys in pursuit of enemy shipping.[1] One day while on the hunt, they inadvertently stumbled upon the English twenty-eight-gun frigate Andromeda. Angelica was captured, the crew were now prisoners and were confined to the warship’s miserable hold for the voyage to Britain.

Once there, abusive language and overbearing threats that were common on shipboard stopped. They learned that they were to be considered prisoners of war and marched to Forton Prison, charged with the crimes of piracy and high treason.[2]

Forton, originally built as a hospital for sick and wounded sailors during the reign of Queen Anne, housed prisoners on a small lot on level ground. A large shed in the center, open on all sides, allowed air to circulate freely with seats for the inmates’ use. Several bleak prison buildings were surrounded by an eight-foot high fence. Daily life revolved around the barracks’ second floor sleeping quarters. Hooks were placed on each side of the building fastened to two rows of posts for hammocks. Each prisoner was given a crude coverlet and a smaller version stuffed with straw that served as a pillow.

A member of the British parliament came to visit claiming to be a friend of the Americans. He talked kindly to the prisoners and said that he was certain there would be a prisoner exchange soon. The prisoners had little confidence this would happen. The distressing thought of continued internment sparked an attempt to dig their way out. Since the prisoners were shut down in the prison from sundown to sunrise, the nights gave them the opportunity to undermine the prison fence and escape. The digging produced a lot of debris that had to be disposed of without alerting the guards. This detritus was scooped into canvas bags and placed in an old unused fireplace chimney. The work usually began around eleven p.m. and stopped about three a.m. when the sentinel’s usual “All’s well” was sounded. After evening’s labor, the tailings safeguarded, the diggers got some rest. Some managed to breach the fence, but most were apprehended and subsequently severely punished.

At last deliverance from captivity appeared to be close at hand and the contemplation raised spirits. On June 2, 1779 an agent’s clerk arrived in the yard and announced that a group of prisoners were to be sent to France onboard a cartel.[3] The next morning the fortunate few were assembled in the yard and, at ten a.m., marched with a forty-soldier escort to the Portsmouth quay and their transport. Along the way, a ragtag group of British musicians and boisterous drummers struck up the tune Yankee Doodle. Perhaps the ragtag band played the song to mock them. Instead, hearing this produced an overwhelming sense of pride among the Americans. Unfortunately, the same tune likely crushed those left behind seeing their comrades leave, about to taste the liberty they so desired.[4]

During the prisoners’ march through Gosport, the unusual sound of the band roused the populace. Crowds, mostly of women, gathered on the streets. Some wished the freed men a safe journey home and others cursed the anxious soon-to-be-freed prisoners, calling them loathsome rebels deserving to be hanged as they trudged their way to the dock. On June 6, 1779 the small ship set sail for Nantz, France. Once Fanning and his mates were ashore in the small town, a large number of Frenchmen warmly welcomed their newly repatriated Americans allies.

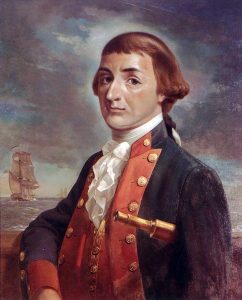

Gustavus Conyngham

Continental Navy Capt. Gustavus Conyngham was temporarily unable to find a warship upon which to serve in his usual capacity; there was a surplus of commanders and a shortage of vessels. Hungering to continue his naval service he opted to take command of the Pennsylvania State Navy’s ship Revenge for a fortnight. His mission was to protect the city’s commerce on the river as a lawful privateer. By the end of April 1779 his letter of marque charter expired. When Revenge set out to the Capes of Delaware on one last cruise, it was without any governmental “paper cover.”

In May while sailing in waters off New Jersey, Conyngham encountered the twenty-gun HMS Galatea. Revenge, out-gunned and out maneuvered, was forced to surrender. Exercising maritime protocol, Galatea’s captain, Thomas Jordan, requested Conyngham’s papers. Since Conyngham could not produce any, he was placed in irons. Once Galatea docked in British-held New York, Conyngham was jailed at the provost’s prison and weighted down with heavy chains fastened to his ankles and his wrists and an iron ring secured about his neck.

Starved and mistreated for some weeks, Conyngham was ordered to be extradited to Britain for trial where he would probably be sentenced to be hanged.[5] Jeered by a loyalist crowd, Conyngham was paraded through the New York streets on a cart to the dock, then rowed to a British packet bound for London. He was placed in the foul-smelling hold for his voyage to England. Before setting sail on June 12, 1779, the American was given the opportunity to write a letter to his wife Anne to inform her of his situation. Conyngham landed at Falmouth, and then he was sent to Pendennis Castle to be confined in a small windowless cell sealed with an ironbound bolted door.

Meanwhile Anne Conyngham used her husband’s letter describing his inhumane treatment as the basis of an appeal to Congress to obtain her husband’s release, contending that the British conduct violated international prisoner of war protocol. Early in the war His Majesty’s government was asked if Americans, held in British prisons, were subject to an exchange of prisoners. The condescendingly reply was, “The King’s ambassador receives no application from rebels, unless they implore his majesty’s mercy.”[6] Because of his service in the Pennsylvania State Navy, Philadelphia’s Society for the Relief of Poor, Aged & Infirmed Masters of Ships learned of Conyngham’s plight and angrily protested Conyngham’s treatment before the Continental Congress.[7] In retaliation the Continental Marine Committee ordered Royal Navy Lt. Christopher Hele, formerly of HMS Hotham and confined in a Boston prison, placed in conditions similar to that of Conyngham.[8] This apparently brought the uncomfortable issue to the Admiralty’s attention and led to Conyngham’s imprisonment at Mill Prison (“Old Mill”) in Plymouth. Thus, he was now regarded as an exchangeable prisoner. At Old Mill, if one committed “the least fault . . . [one would spend] 42 days in the dungeon on the half of the allowance of Beef & bread — of the worst quality . . . dogs, cats rats even grass [was] eaten by the prisoners.” [9]

While at the notorious penal complex, Conyngham tried several imaginative escapes. Once he nonchalantly walked out of the prison gate with a group of visitors, but was apprehended after he started to go his own way. In another attempt, he dressed in a dark suit and put on wire-rimmed spectacles in the disguise of a visiting doctor. He pretended to be engrossed in a book and walked nonchalantly through the prison gates. A prison tradesman who knew many of the prisoners recognized Conyngham and he was recaptured. On one particular stormy day on Britain’s south coast, the guards were preoccupied with the weather. He slipped by the sentries again, but was soon captured before he got very far. Finally, on November 3, 1781 Conyngham succeeded in escaping with a group of about fifty other Americans who had dug a tunnel under the prison wall.[10] Conyngham and a few fellow escapees eventually crossed the English Channel to Holland. Conyngham returned to Philadelphia on the Hannibal whose crew included ninety-five fellow escapees from British prisons.[11]

Joshua Barney

Continental Navy Lt. Joshua Barney, recently extradited to England onboard HMS Yarmouth, was imprisoned at the “Old Mill” and tried to escape shortly thereafter. Soon caught, he was sentenced to thirty days in solitary confinement and placed in irons. The warden ordered him closely watched, believing Barney was an escape risk. With a lot of time to think, the wily American concocted a complex escape plan. First, he pretended to injure his ankle in the prison yard. In full view of the guards, fellow prisoners treated the sprain and thereafter Barney hobbled about on an improvised crutch. Seemingly now unlikely to attempt an escape, the guards relaxed their vigilance on him.

Next Barney acquired a nondescript oversized greatcoat that covered whatever garments he wore underneath. Local merchants frequently came to the prison to provide personal goods for the prisoners. Barney paid a tailor to make and alter a British naval officer’s uniform for him and smuggle the outfit into the prison. Barney then enlisted some fellow prisoners to help him in his plan. First a very tall broad-shouldered fellow was asked to loiter near the wall and be in position when needed. Next Barney enlisted a lad about his size to retrieve Barney’s greatcoat at the proper moment, don it and, later, substitute for Barney at rollcall so the lieutenant would not be missed. Barney had cultivated a friendship with a British sergeant of the guards who had served in America; having developed confidence in their relationship, he asked him to help in his escape.

The day of his planned breakout, Barney limped to the prison gate on his crutches.[12] His prison guard friend signaled that most of the guards were at lunch. Barney returned to the barracks, donned the secreted officer’s uniform under his greatcoat and alerted his conspirators. As they took theirstations in the yard, Barney strolled conventionally across the prison yard to where his tall friend had positioned himself next to the wall. The few patrolling guards were distracted by a prearranged commotion on the other side of the prison yard. The sergeant then signaled that the coast was clear. Barney quickly ran to his tall burly friend, was hoisted onto his accomplice’s shoulders and from there to the top of prison wall. He then dropped to the ground on the other side and tossed the greatcoat back into the yard. The young lad retrieved it and limped away. Barney nonchalantly passed the sergeant several guineas along with a returned wink. Now disguised as a British naval officer, he assumed a well-practiced military bearing. Barney strolled past sentries and through the gate without a challenge, exchanging smart naval salutes along the way. Now free, he made his way to a London safe house and eventually to a clandestine channel crossing to France.[13]

In more recent times Robert Frost stated, “Freedom lies in being bold.”[14] The accounts of these three seafarers provide evidence of the wisdom of the renowned poet.All three of these Revolutionary War mariners subsequently had United States destroyers named after them.

[1]A privateer was a privately owned, officially-sanctioned vessel whose purpose was to capture enemy ships during wartime. The incentive of the owner and crew was profit. Vessels and their cargoes were brought into admiralty/maritime court, sold at auction and the proceeds divided by established portions between investors, agents, ship’s officers, and seamen. Privateers could intimidate the enemy, weaken its commerce and disrupt its supply lines. The British Navy characterized American privateersman as mercenary pirates; it was a time-honored practice employed by all nations, but Britain did not recognize the United States as a sovereign nation.

[2]Forton Prison was located across Portsmouth Harbor and approximately a mile northwest of Gosport. Captives had little to eat and both the quality and quantity of food was the subject of continuing prisoner complaints. Clothing was also a problem. Many of the prisoners had their possessions taken during their shipboard captivity and some arrived at Forton half-naked.

[3]A cartel was a vessel used to exchange prisoners between hostile powers.

[4]Fanning’s incarceration at Forton lasted thirteen months.

[5]Being hanged in public was a common punishment for pirates in England, although less common during the reign of George III. Perhaps Conyngham’s disdained Irish ethnicity precipitated his extraordinarily cruel treatment.

[6]H. Hastings Weld, Benjamin Franklin: His Autobiography; with a Narrative of His Public Services (New York, NY: Harper and Brothers, publishers, 1848), 497.

[7]Library of Congress, ,” Naval Records of the American Revolution: 1775-1788 (Washington, DC: Library of Congress. Manuscript Division, 1906 ), 110-111 (NRAR).

[8]NRAR, 114; Robert Wilden Neeser, ed., Letters and papers relating to the cruises of Gustavus Conyngham, a captain of the continental navy, 1777-1779 (New York: De Vinne press, 1915), 184, 192.

[9]Neeser, Letters and papers,11.

[10]Nesser, Letters and Papers,190.

[11]Nesser, Letters and Papers,12.

[13]Mary Barney, Biographical Memoir of the Late Joshua Barney. From Autobiographical Notes and Journals in the Possession of his Family, and Other Authentic Sources (Boston: Gray and Bowen, 1832), 88-90. and Louis Arthur Norton, Joshua Barney: Hero of the Revolution and 1812 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2000), 55-56.

[14]Phillip Hamburger’s quote of Robert Frost in The New Yorker, December 13, 1952, 167.

2 Comments

Norton has done a wonderful job on bringing to the fore a little understood or studied aspect of the Revolution — at sea and then captured. Although I was most familiar with Barney’s story — thanks, in large part of Steve Vogel’s “Through the Perilous Fight” on the War of 1812, these three were “bold men” indeed.

Also recommend Tim McGrath’s “Give Me a Fast Ship,” which includes treatments of Fanning (who was imprisoned a few more times) and Conyngham, as well as Jones and Barry.