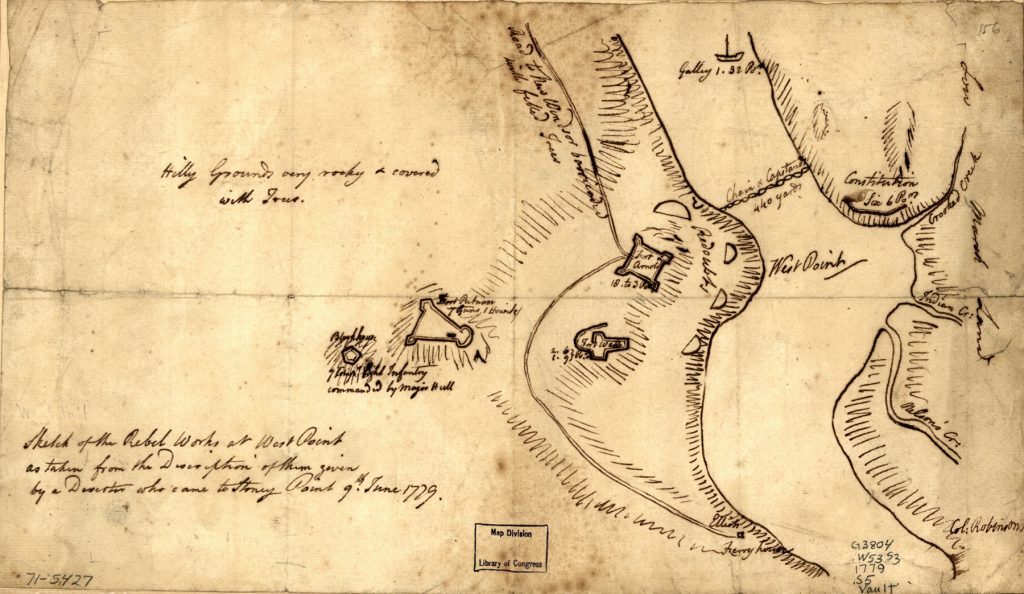

Thomas Machin claimed to be a British-trained engineer. His record of achievements in the United States suggests the claim was true. Most of his past, however, remains largely unknown and what is known is both mysterious and controversial. And, yet, he was one on whom Gen. George Washington placed a huge wager in 1776 by summoning him to design, fashion and install across the mighty Hudson River between Fort Montgomery and Anthony’s Nose a chain to block the Royal Navy, soon to be assembling in New York Harbor with upstream intentions.[1] And, then, when the Fort Montgomery chain was cut by the British, to repeat this astounding accomplishment with a new chain strung between West Point and Constitution Island.

While much is different in usage and development along its banks, the river, itself, has changed little since the late eighteenth century, when the struggle for control became an important element of the Revolutionary War. It is an arm of the sea—an estuary in which waters both fresh and salt mix in a four-foot tide extending 150 miles from its mouth in New York Bay north to Troy, New York. And, as a narrow arm of the sea formed by glacial erosion and bordered by steep cliffs, the Hudson may fairly be described as a fjord.

From Lake Tear in the Clouds near Mt. Marcy to New York Bay, the river flows a distance of 315 miles. For some sixteen miles from Newburgh Bay to Peekskill Bay, the Hudson Highlands rise high above a perilous channel known as “The Devil’s Horse Race.” The deepest sounding, at the southern end of Martyr’s Reach opposite West Point, is 216 feet; the river’s depth at Fort Montgomery is almost the same. Tides rise and fall in this stretch of river by one yard. The Highlands boast dramatic displays of gneiss and granite, etched, rounded and tossed up by the forces of glaciation during the last Ice Age.[2]

Controlling the Hudson was considered a strategic necessity by both British and American military planners. For the British, control would force an end to the Revolution. For the Americans, control would enable the battle to continue from north to south, from east to west. General Washington was vehement in his strategic judgment that controlling the river was “of infinite importance.”[3] East of the Hudson there was no flour; west of the Hudson there was no meat. Beyond these commodities, communication, movement of forces and supply lines for foodstuffs, munitions, horses, tents and other essentials of war had to remain free to pass back and forth across the river.

In Philadelphia, on May 25, 1775, the Continental Congress ordered a post in the Highlands, with batteries on both sides of the river and obstructions to navigation.[4]

In London, on July 31, 1775, the British Ministry ordered its forces in America “to get possession of New York and Albany . . . to command the Hudson and East Rivers . . . so as to cut off all Communication by Water between New York and the provinces to the northward of it, and between New York and Albany, except for the King’s service . . . By these Means, the Administration and their Friends fancy that they shall soon either starve out or retake the Garrisons of Crown Point and Ticonderoga, and open and maintain a safe Intercourse and Correspondence between Quebeck, Albany and New York, and thereby afford the fairest Opportunity to their Soldiery and the Canadians, in conjunction with the Indians [to] distract and divide the Provincial Forces . . . and compel an absolute Subjection to Great Britain.”[5]

The threat of losing control of the Hudson to the British was palpable. In New York Bay some 200 British vessels had gathered, including a substantial share of the global British fleet of warships. The Royal Navy already controlled both Canada and the Atlantic coast. General Washington saw the Highlands as the best choke point to stop the British fleet. He assigned Thomas Machin the task of determining where and how to achieve that goal.

In his July 21, 1776 letter to Machin, then in Boston, Washington wrote:

You are without delay to proceed for Fort Montgomery, or Constitution in the High Lands on the Hudson’s River, and put yourself under command of Colo. James Clinton or the Commanding Officer there, to act as Engineer in completing such Works as are already laid out, and such others as you, with the advice of Colo. Clinton may think necessary—‘tis expected and required of You . . . that you pay strict and close Attention to this Business . . . and drive on the Works with all possible Dispatch.[6]

In an accompanying letter to Col. James Clinton, the general described Machin as “an ingenious Man,” one who “has given great Satisfaction as an Engineer.”[7]

About Thomas Machin, two stories persist. One, promoted by Machin, claims him to be the son of John Machin, a distinguished mathematician who was secretary to the Royal Society—but John Machin died without having children. This account has Thomas Machin coming to America in 1772 to explore a copper mine in New Jersey for some British investors, staying in New York City and then moving to Boston, where he became allied with the colonists in their quarrel with England. In this story, he joined the “Sons of Liberty” and participated in the Boston Tea Party in December, 1773. Given his training in England as both an artilleryman and engineer, he helped in planning the defenses at Bunker Hill, where he was wounded in the ensuing battle.[8]

The other story, based on known primary sources, is by far more convincing.[9] It has Thomas Machin enlisting on February 17, 1773 in the British Army’s 23rd Regiment of Foot while it was preparing to ship out to America.[10] The Regiment sailed in April and arrived in New York in June of that year. The Regiment’s muster rolls record Machin’s desertion on July 28, 1775, and two British officers took the time to make note of it, a clear indication that Machin was unusual among soldiers. Lt. Richard Williams of Machin’s regiment wrote:

Last night Thos. Machin, soldier in our Regt. deserted when sentry on fire boat in the river near the neck. He went off in the Canoe go to this float, he took the other man’s firelock with him, as it was that man’s turn to lay down, this fellow will give them good intelligence of our Works, for he was a pretty good Mechenik & knew a little of fortification, he invented a new carriage for guns on a pivot &c. his books & instruments were sent for to the General’s.[11]

Staff officer Maj. Stephen Kemble recorded in his diary: “Two Men of the 52d. Regiment Deserted from the Advanced post on the Charles Town side, and one from the 23d., a sensible intelligent fellow, some knowledge of fortification and Gunnery.”[12]

A newspaper reported, “A very intelligent soldier, belonging to the 23d regiment, who deserted from the enemy last week, and who is known by several gentlemen in our army, we are well informed, made oath before his Excellency General Washington,” followed by some details of information that Machin—the only deserter from the 23rd Regiment during July and August—delivered.[13]

Machin’s own autobiographical account, while not mentioning military service, has him coming to America at the same time, and being in the same places, as the 23rd Regiment from 1773 through 1775 (i.e. traveling to New York, spending time in New Jersey, then going to Boston). The first mention of Thomas Machin in American documents comes shortly after July 28, the date of his desertion. No mention in Boston or elsewhere of a Thomas Machin has been uncovered by historians before the date of desertion by the British soldier of that name – the one with engineering skills highly unusual for a private in the British infantry.

What makes the story of Thomas Machin and his chains so compelling? It is a combination of many factors. They begin with the peculiar facts of the man himself, a deserter from the British Army who, instead of boasting of this laudable migration to the Continentals, where he served with distinction, pretended throughout his life to be something else. Why would he deny facts that any man with his record would find good reason proudly to proclaim? Why did he enlist in the first place? What drove him, at enormous risk to his life, to desert? And to engage so importantly in the American battle for independence? Before doing so, had he planned to join Washington’s Army? Through what means did it happen, for certainly Washington would take care in screening former British soldiers? Did the shame of being labeled a deserter outweigh the pride he could justifiably claim in joining the Continentals? Questions like this trigger one’s imagination, invoking a desire to complete his tale.

Machin was highly intelligent, especially in his ingenious capacity to improvise and design all manner of tools, machines and the like, to resolve problems of physics, to not just understand newfangled things, but to build them. His claim to having been trained as an engineer is supported by his record with the Continentals. And beyond whatever formal training he experienced, his accomplishments with the chains define him as what for centuries has been admiringly referred to as a “good Mechanic.” And all that he did on the Hudson River gave honored evidence to his credentials, which were not well known when Washington wagered control of the Hudson on this engineer.

Thomas Machin’s achievements on the river are not well known, written about, understood or appreciated. There are books focusing sharply on the Hudson River’s role in the War that contain excellent discussion of this subject.[14] But among most general accounts of the War there is a remarkable lack of prominence to either the man or his chains.[15]

In fact, Thomas Machin and his chains offer much to attract one interested in the history of the American Revolution. I spend as much time as I can find to bicycle in Harriman State Park, parking my car on the east side of the Hudson at Bear Mountain Bridge and riding across the river and up the mountains accessible along good roads such as Seven Lake Drive. On each crossing, the 1,800-foot span brings to mind what happened on the river in 1776 and 1777, and at Forts Clinton and Montgomery, the latter now an engaging museum just north of the bridge on the west side, managed with accomplishment by Grant Miller.

The immensity of every aspect of Thomas Machin’s work there, and at New Windsor and West Point in 1778, grew on me with each ride. His was not an ordinary war mission, ordinarily achieved. It began to seem to me the stuff of which an Homeric-like tale could be woven. And, upon discovering the fantastic stories Machin made up about himself, the puzzle of this man drew me in to what I began to imagine could be a complex and even compelling story. There were at hand many libraries with relevant materials, such as the New York Library, the New York Historical Society, the West Point Museum, the Sterling Forest State Park, the Museum at Washington’s Headquarters in Newburgh, and the Fort Montgomery Museum. Librarians at each one offered uncommon interest and help, making pursuit of this history a serial pleasure.

The more history one uncovers, the more surprising the apparent lack of interest shown by historians in Thomas Machin and his chains. One need only consider the Royal Navy assembled in New York Harbor, some 200 ships, the largest armada ever gathered in one place, to begin to appreciate the audacity of General Washington in imagining obstructions adequate to block this mighty fleet from sailing up the river to Albany and beyond. An audacity not much noted. Or begin to admire his judgment in picking Thomas Machin to fulfill this dream, not once, at Fort Montgomery within a year of his arrival there, but again, within six months after the British cut the first chain, by completing the design, manufacture, transport and installation of a new and far stronger chain at West Point. A judgment not noted in historical accounts.

Consider the fact that at its narrowest points, Fort Montgomery and West Point, where the spans called for chains in length at least 1,650 feet and 1,500 feet, respectively, the waters moved swiftly. At maximum ebb tide, for example, more than sixty-five million gallons of water pour south each minute through the twenty-six-fathom channel between Fort Montgomery and Anthony’s Nose. Thomas Machin had to design a chain strong enough to withstand this current but not so heavy that it couldn’t be supported on rafts strung across the river. The chain would need swivels to allow for twisting, clevises to allow for connections, and capstans on shore to pull it tight. For the Fort Montgomery chain, there were some 850 links weighing more than thirty-five tons, supported by rafts of pine logs two feet in diameter. And, yet, who could say whether this chain, or the much stronger one at West Point, could stop an 850-ton British warship under full sail with a following tide? In fact, the chain at Fort Montgomery broke twice in the fall of 1776, just from the force of tidal flow. With the defects discovered by Machin in the chain repaired, it was reinstalled in the spring of 1777 and lasted until October 6 of that year, when the British, in one of the most audacious undertakings of the War, overcame defenses at Fort Montgomery and its sister Fort Clinton just to the south of Popolopen Creek, and cut the chain.

This remarkable achievement of the British, for the most part ignored in the historical texts, could not have succeeded without the help of Beverly Robinson, a Loyalist who owned a large house in Garrison, across the river from West Point, and knew the trails and terrain in the area. He remained loyal to the Crown and had gone to New York City to organize a Loyalist regiment to fight with the British. He and his regiment sailed with Gen.Henry Clinton’s forces and was happy to lead them through the Highlands, a feat considered for the British forces improbable if not impossible without local guides. Despite the presence of large numbers of Loyalists in the Hudson Valley, Washington and his generals failed to consider the possibility of displaced residents serving as guides as Robinson did to enable a land-based attack on the two Forts.

Whereas the first chain was composed of links one and a half to two inches square, the one forged for West Point by the Sterling Iron Works used links of Sterling grade bar iron two and a quarter inches square. There were 750 links spanning 1,500 feet of water from West Point to Constitution Island. Each link weighed about 114 pounds; in all, the links consumed sixty-five tons of forged iron. Sets of nine of them were connected by clevises. It is hard to grasp the scale of these links without seeing them up close, touching them, running your hand along them. This you can do by visiting what the Military Academy calls “the Great Chain,” a collection of the original links displayed at Trophy Point just off Cullum Road running through West Point.

The foundry was at Sterling Lake, some thirty-two miles distant from New Windsor, along the Central Valley. Ox-drawn sledges, each carrying nine links plus a clevis and pin, could not travel directly to West Point due to the mountains separating Sterling Lake from that site. Instead, they went a much longer route up the Central Valley to New Windsor, where Machin oversaw their placement on huge rafts to be floated down the Hudson to West Point. Whether by bike or on foot or in a car, traversing this route today yokes one’s imagination to the scene of those oxen, straining to move the heavy cargo to the shores of the Hudson River at New Windsor. On my bike I found visualizing this undertaking as easy as it was thrilling.

The Herculean task Thomas Machin set for himself and his various teams of lumberjacks, ox drivers, and river-men is hard to comprehend; impossible to exaggerate. This astounding feat of design, engineering, manufacture, transport, assembly, and installation was completed in three months, beginning on February 2, 1778, when the contract with Sterling was signed, and ending on April 30, 1778, when the chain and a boom just below it to help block the Royal Navy were safely installed across the river. To begin to appreciate the challenge Machin faced, one should remember that neither the electric motor nor the internal combustion engine had been invented. Electricity was observed in the sky but not yet tamed for industrial or residential use. No chain saws. No tractors or trucks. Hauling was left only to horses, oxen, and humans.

The contract for making the chain specified that Sterling would use “utmost endeavors to keep seven fires at forging and ten at welding” twenty-four hours a day.[16] And this they did, consuming forests of wood to create the charcoal required to feed those fires.

The pine logs needed for chain and boom would have meant over 750 of these conifers found, cut down, trimmed, and dragged to New Windsor. The pine was required for its high specific gravity, or buoyancy, to float despite the weight of the chain’s links. Cutting and moving these trees was an almost unimaginable project, yet one completed in well short of three months. Stretched out end to end, the logs needed for the chain’s rafts and protective boom would reach over two miles. Just as it takes close inspection of the chain links at Trophy Point to grasp their size, so can the immensity of the boom only be appreciated by examining one of the eighteen-foot logs almost two feet in diameter displayed at Washington’s Headquarters in Newburgh, New York.

And then consider getting the rafts and boom down to West Point and strung across the river, without outboard motors to use against strong tides turning every six hours. And without lights to enable movement when the tides turned downstream in darkness. (Machin solved this problem by having men build fires along the shoreline, casting enough light to enable the rafts to continue their voyage.)

And Machin devised an ingenious solution to the problem of how to allow passage of friendly river traffic after the chain and boom were installed, by deploying clevises and anchors permitting the chain and boom to be opened along the west shore.

Some might think it hyperbole to compare the project at West Point to Grant’s extraordinary march to attack and subdue Vicksburg, or construction of the Pyramids. Other comparisons to the great chain installation at West Point might include such engineering feats as Hoover Dam, Brooklyn Bridge, or the trans-Atlantic cable. On reflection, after diving deeply into the facts of all that was accomplished in barely three months, the West Point project, extraordinary in so many ways, makes any of these comparisons a worthy mirror to use in measuring Machin’s accomplishments.

Throughout the period from Thomas Machin’s arrival at Fort Montgomery in June 1776 to April 30, 1778, when he could admire the jewel-like chain forming an arc across the Hudson at West Point, he encountered bureaucratic obstacles equal in difficulty to the physical ones he was attempting to establish against the Royal Navy. Well documented, these included ever-changing chains of command, with weakened links often giving way, and the successive imposition between Machin and the project he was appointed to complete of two self-promoting “experts,” Bernard Romans and Louis Deshaix de la Radiere. Each of them possessed a swelling ego, the conceit of infallibility, ears tone-deaf to the views of others and an intransigence that, in combination, delayed each installation for weeks, while causing anguish and wasted energy for all involved. In hands not as sensitive and skillful as those of Thomas Machin, these challenges to progress would probably have been far worse, if not fatal to the enterprise. Despite a well-developed ego, Machin must have learned somewhere along his career path not to wear it on his sleeve. He demonstrated the remarkable ability to disregard insults, fret not over disagreements and with a low profile simply keep moving ahead toward his goal, somehow finding a way over, under or around each of the hurdles placed in his way.

Once installed, work on the chain was not complete. At risk of being destroyed in the winters by ice forming across the river, it had to be taken down each fall and then reinstalled as soon as the ice broke up in the spring. At West Point, this step was performed over four winters following initial installation in the spring of 1778.

The strategic importance of the chains to the War’s outcome is the subject of conjecture and debate. The Fort Montgomery chain was cut before it could be tested against the Royal Navy’s fleet. And the West Point chain was never tested.[17] Whether it served to deter the British from seeking control of the Hudson River, which records show it considered essential, is unknown. Unknown, but highly plausible. Indeed, the risky decision to launch an attack against Fort Montgomery and its sister, Fort Clinton by land over unfamiliar and treacherous mountains in order to cut the chain, instead of testing it with the Navy, suggests both the importance attributed to this obstacle by the British and the fear they had of trying to break it with the fleet.

The fact that the West Point chain was never tested may help to explain why it and the achievements of Thomas Machin seem not to have been accorded much weight by historians. The key is to consider what didn’t happen on the Hudson. The lack of a test of Royal Navy strength against the chain and supporting gun batteries tends to divert attention to other events. The study of this non-event pales in interest to, for example, the battles of Trenton and Princeton, of Bennington and Saratoga. And, yet, explanations for this non-event can lead to important historical insights, including the extraordinary wisdom on the part of Washington in picking Machin and insisting on the two chains, and the extraordinary engineering skill, invention and drive on the part of Machin in fulfilling Washington’s strategic vision.

At West Point, given the sheer size and strength of the chain and of the boom below it, the British spies reporting on the installation must have been impressed by the scale of the obstruction and its potential for repulsing the enemy. The important point, which General Washington understood better than anyone except, perhaps, Thomas Machin, was that the chain could deter the British without being tested. Therein lies its supreme importance to the war, and an easy excuse, among many others, for telling the story of Thomas Machin and his chains.[18]

[1]George Washington to James Clinton, July 21, 1776, Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-05-02-0301(fn.1 contains Washington’s orders to Thomas Machin as of this date). Washington told Clinton: “The Bearer Lieut. Machine I have sent to Act as an Engineer in the Posts under your Command, and at such other places as may be tho’t necessary, he is an ingenious Man, and has given great Satisfaction as an Engineer, at Boston from which he is just returned.”

[2]Frances F. Dunwell,The Hudson River Highlands(New York: Columbia University Press, 1991), 1-9.

[3]See, e.g., The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources, 1745-1799, ed. John Clement Fitzpatrick(Washington, DC: U. S. Government Printing Office, 1931-1944), 4: 399; Washington to d’Estaing, September 11, 1778, The Papers of George Washington: Revolutionary War Seriesvolume 16, July – September 1778, ed. David R. Hoth, (Charlottesville and London: University of Virginia Press, 2006), 570-74.

[4]Edward Manning Ruttenber, Obstructions to the Navigation of Hudson’s River: Embracing the Minutes of the Secret Committee (Albany: J. Munsell, 1860), 7.

[5]Ibid., 1-4. In the Introduction, Ruttenber writes: “The Student of American History is familiar with the Fact, that to obtain Control of the Navigation of Hudson’s River, was a Favourite Project with the British Ministry, during the whole Progress of the War of Independence.” If true, it seems highly plausible that what the Continental soldiers took to calling “General Washington’s Watch Chain” played an important role in defeating this cherished goal of the British.

[8]The most detailed account of Thomas Machin’s personal history, as reported by him and his family, is contained in Jeptha R. Simms,History of Schoharie County(Albany: Munsell &Tanner, 1845). This account has been widely accepted by historians despite being to a large extent unsupported by original source material. See, e.g., Lincoln Diamant, Chaining the Hudson(New York: Fordham University Press, 2004), 11.

[9]See J. L. Bell, “The Early Life of Thomas Machin,” boston1775.blogspot.com/2013/03/the-early-life-of-thomas-machin.html; “The Holes in Thomas Machin’s Biography,” boston1775.blogspot.com/2013/03/the-holes-in-thomas-machins-biography.html; “The Truth about Thomas Machin,”boston1775.blogspot.com/2013/03/the-truth-about-thomas-machin.html. Private correspondence among Don N. Hagist, Grant Miller and Harry Vderci, from June 9 to June 20, 2016 contains compelling evidence and analysis in support of J.L. Bell’s conclusions.

[10]Muster rolls, 23rd Regiment of Foot, WO 12/3959, The National Archives of Great Britain.

[11]Richard Williams, Discord and Civil Wars(Buffalo, NY: Easy Hill Press, 1954), 26.

[12]Stephen Kemble, “Journals of Lieut. Col. Stephen Kemble,” Collections of the New York Historical Society for the year 1883 (New York, 1884), 50.

[13]Massachusetts Spy, August 9, 1775.

[14]North Callahan, Henry Knox: Washington’s General(New York: Rinehart & Company 1958), 33-60; Atkinson, The British Are Coming(Henry Holt and Company 2019), 234-37.

[15]George C. Daughan, Revolution on the Hudson(New York: Norton 2016); John Ferling, Almost A Miracle(New York: Oxford University Press 2007); David McCullough, 1776(New York: Simon & Schuster 2005); Stephen Conway, The War of American Independence: 1775-1883 (London: Edward Arnold 1995); Robert Leckie, George Washington’s War: the Saga of the American Revolution (New York: Harper Perenial 1992); Jeremy Black, War for America: The Fight for Independence 1775-1883(Phoenix Mill: Alan Sutton Publishing Ltd. 1991); Ira D. Gruber, The Howe Brothers and the American Revolution(New York: Norton 1972); John R. Alden, AHistory of the American Revolution(London: MacDonald and Co Ltd. 1969); James Thacher, Military Journal, During the American Revolutionary War 1775 to 1783(Hartford: Silas Andrus & Son 1854; republished by Forgotten Books 2012); Charles Stedman, The History of the Origin, Progress, and Termination of the American War(London: J. Murray, Fleet Street 1794). In none of these books is Thomas Machin or his chains mentioned.

[16]Diamant, Chaining the Hudson, 187 (containing the entire Articles of Agreement between Noble, Townsend and Company, Proprietors of the Sterling Iron Works and Hugh Hughes, Deputy Quartermaster General to the Army of the United States).

[17]West Point Cadets, using a computer model to test the ability of the chain to withstand the weight of a frigate, concluded that it couldn’t even stop a sloop. West Point Fortifications Staff Ride,28, www.westpoint.edu/sites/default/files/inline-images/WEST%2520POINT%2520FORTIFICATIONS%2520STAFF%2520RIDE_0.pdf. Gun batteries on shore were considered an essential element of the chain defense. Success didn’t need to depend on actually repelling British warships; Success could be achieved through deterrence alone and do so with less loss of life.

[18]The author has completed an historical novel based on Thomas Machin’s achievements on the Hudson. Titled Chains Across the River,it should be published before year-end, available wherever books are sold.

Recent Articles

Joseph Warren, Sally Edwards, and Mercy Scollay: What is the True Story?

This Week on Dispatches: David Price on Abolitionist Lemuel Haynes

The 1779 Invasion of Iroquoia: Scorched Earth as Described by Continental Soldiers

Recent Comments

"Contributor Question: Stolen or..."

Elias Boudinot Manuscript: Good news! The John Carter Brown Library at Brown...

"The 1779 Invasion of..."

The new article by Victor DiSanto, "The 1779 Invasion of Iroquoia: Scorched...

"Quotes About or By..."

This well researched article of selected quotes underscores the importance of Indian...