In September 1780, writing from Hillsborough, North Carolina, just one month after the disastrous defeat at Camden, Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates penned a disconcerted letter to Thomas Jefferson, the then governor of Virginia, broadly sketching the situation in the colonial South: “Should Wilmington in this State and Portsmo[uth] in Yours, be the posts they intend to take, I conceive the Southern Army would be intirely misplaced at Charlotte Salisbury and the Ford upon the Yadkin.”[1]

The situation in the Carolinas had deteriorated for the Patriots after Camden. Gates not only suffered a rousing defeat in battle, but thoroughly embarrassed the Continental Army when he fled the scene. Duel British victories at Charlestown in May and Camden in August 1780 put the patriot cause in the South on a meager footing. The presence of the Crown’s army in the South sought to further incite Loyalists to curb the rebellion. Although Gates reminded Jefferson that the British remained vulnerable at times, British strength had been continually fortified. Their fortification continued on September 26. Gen. Charles, Lord Cornwallis and the British Army overran the Patriot militia defending the small backcountry town of Charlotte, North Carolina, near the Catawba River. British cavalry pushed the Patriot militia from the small courthouse at the center of town, and secured another rout of the Whigs in the South. Charlotte was now in British hands. Since the transition by British leadership to a Southern campaign, they had seen demonstrable victories throughout the Carolinas and Georgia, further emboldening British commanders and their backcountry allies.

The Carolina backcountry was the hotbed of civil war as Cornwallis overtook Charlotte. Difference of sentiment concerning British oversight boiled over in towns and cities to wholesale violence. Neighbor turned on neighbor with suspicion and ferocity. Tories and Whigs fought a constant campaign of indistinct violence. Although the British held Charlestown and Charlotte, the backcountry had no distinct loyalties. Militia mustered in various towns. Towns even rose in division, as one portion declared for Parliament and the other Congress. Tensions and emotions catalyzed into actions. Loyalist militia marauded the countryside as far as the Appalachian Mountains, while Patriot militia pushed to regain their losses north of Charlotte and in the central Carolinas. An increase in British strength and presence emboldened a particular group of Tories from Surry County began to move to support Cornwallis.

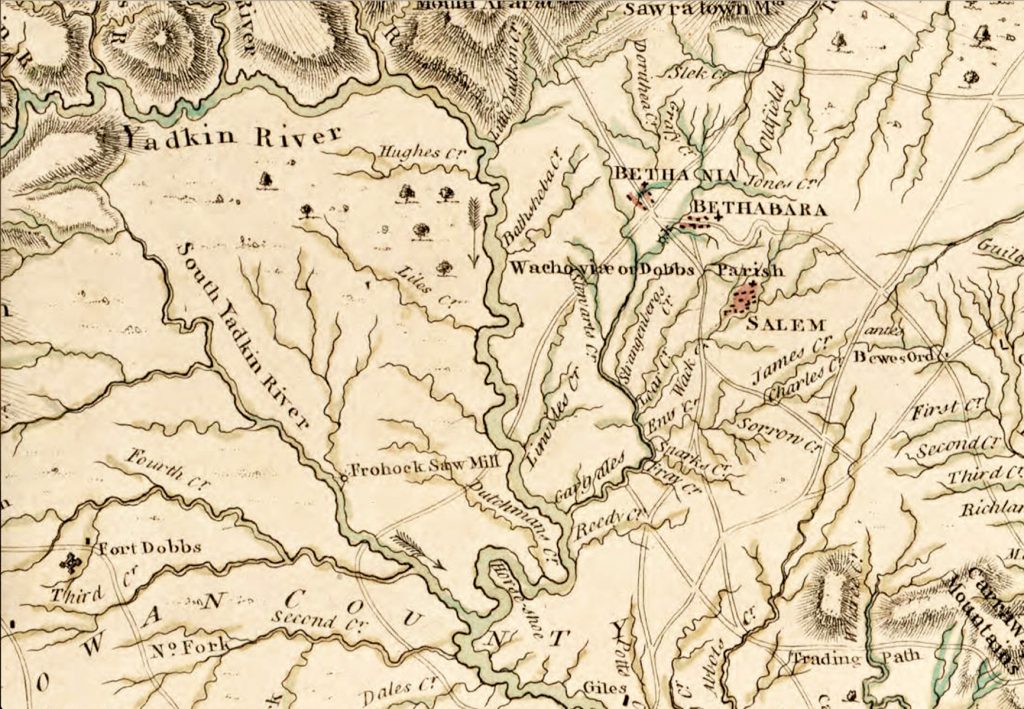

Surry County, North Carolina, was a large territory reaching into the Yadkin Valley. Its breath and width allowed it to stretch into the thick and beautiful backcountry of the Appalachian Mountains and its great rolling foothills. The backcountry was thickly forested and laced with creeks and streams meandering between rolling foothills. As the British pushed into this southern backcountry, Surry county Tories formed a militia and moved south following the path just east of the Appalachians. As they moved, rumors spread. The rumors were filled with tales of violence, and yet without confirmation or hindrance.

On October 4, testifying to the rumors, Gen. Jethro Sumner informed Major General Gates of the approaching Tory throng. A party of Tories, only recently known to him by enclosed letters from Col. William Preston, had begun burning and pillaging. Marauding through the countryside violently, the Tories apparently had gone largely unnoticed until now. Even Col. Martin Armstrong had heard nothing of the matter as he left Surry County the evening of Saturday, September 30. Nevertheless, the next morning after Armstrong left town, “this rising to imbody began.” Sumner included in his letter to Gates the information known about the Tories: “we have accounts of the Tories imbodying in Surry County, in the fork of the Yadkin river, & had actually killed one Hedgspeth, the sheriff of the county.” With the weak and seemingly absent command of Gates, concern fell on cold and deaf ears throughout the countryside, as the violence spreading in North Carolina grew. Given the vastness of his responsibility, General Sumner had other concerns at the time. However, the general improvement and possible strengthening of Cornwallis’s forces put the Surry County militia at the forefront of coming confrontation. Stopping the Tories would be almost unreasonable, for “the extent of the Country between this & Charlotte is too great.”[2] Sumner concluded that, although they were near the fork of the Yadkin river, they could also cross near McGoon’s Creek as they moved south to reach Cornwallis and Charlotte. Sumner’s concern was muffled by the extension of Tory and Whig conflict across the country under his command.

On October 7, Colonel Armstrong responded to Sumner’s letter with alarm. The Tories, “are too strong for what force I can raise. They are determined to have me Prisoner. Their number is about 300.” As a resident of Surry County and knowing the strength and presence of these militia men, Armstrong could be targeted for his Patriot sentiment. But, Surry County militia contended themselves with burning and pillaging in the distant countryside, far from the county seat of Richmond. Armstrong further outlined for Sumner his expectation that they would return to central Surry County no early than October 13. Their return would not be met with the force required. In ever-increasing alarm, Armstrong complained to Sumner that, “the men I have cannot be depended on, & of a truth my present Circumstances are bad.” He continued to stress to Sumner that, “unless some timely Aid comes [I] am afraid the enemy will persevere further in their hostile Scheme already begun.”[3]

As the Tories pressed to return to the county seat of Richmond and move southward to the Ford at the Yadkin, the Whigs feared their inability to turn back their violent advances. Leading this pillaging company was “Col. [Gideon] Wright and his brother,” Hezekiah, whose, “ignorance is to be dreaded, having not the least principles of Honor or honesty.”[4] Both Gideon and Hezekiah Wright were veterans of the French and Indian War in New York. After moving to North Carolina, Gideon Wright sided with Provincial North Carolina Gov. William Tryon during the regulator movement and rose to the rank of colonel.[5] Having earned an officer’s rank under British rule and with the movement quelled, he returned to the newly-established Surry County and founded its county seat. He did so over and against the Armstrong family, of which Col. Martin Armstrong was a member. When the Revolution broke out, the Wrights and Martin found themselves on opposing sides of hostility. Now Gideon and Hezekiah were leading a Tory militia of “bandits and plunderers” throughout western North Carolina.[6]

As urgency grew, mustering a force became more pressing and concerns grew that the Tories would join forces and move south. Trouble developed in Surry and southward as Colonel Wright returned with his, “3 or 400” men. General Sumner again wrote General Gates concerned about their advancement. The Wright brothers had already sent an advanced guard “into Charlotte to get a way open for them to join the British army.” Sumner’s letter deliberated to Gates that he would be willing to send three-hundred soldiers to disperse the Tories, but the movement of his men at that time was impossible.[7]

While the Tory militia under Colonel Wright terrorized the countryside while they headed for Charlotte, Joseph Williams, living along the Yadkin River, received word of their approach. At the lowest point in the river, the Shallow Ford had been used by native peoples for centuries to cross the Yadkin. Located on the northern branch of the Yadkin in the interior of North Carolina, the ford was near the Moravian town of Salem. Its necessity was evident to all sides fighting in the interior. The ford also lay strategically on the Great Wagon Road, which ran from Pennsylvania to Georgia and was used by colonists and natives to transverse the interior of the East Coast of North America.

A Colonel in the Patriot militia, Joseph Williams received his commission from North Carolina Gov. Richard Caswell in June 1779, when he accompanied a surveying party to mark out the latitude that would divide Virginia and his home colony.[8] Prior to the colonial Declaration of Independence, Williams had married Sarah Lanier and moved to the banks of the Yadkin near the Shallow Ford. Having been a clerk in Surry county and having maintained his rank of colonel in the Patriot militia, Williams likely knew Martin Armstrong, Gideon Wright, and Hezekiah Wright. And he knew the importance of Shallow Ford.

As rumor spread that a Virginia company under Maj. Joseph Cloyd and Capt. Henry Francis was in pursuit of the Surry County Militia. Less is known about Major Cloyd than Colonel Williams, but his force was trained and already formed, ready for action against Wright’s. As the Virginias were in pursuit, Colonel Wright lead his militia through “Richmond [the Surry County seat] to the Old Moravian Town [Salem], intending to cross at the Shallow Ford over the North branch of the Yadkin to join the British.” According to General Smallwood, they were reported to have had 900 men in their company.[9] John Peasley contradicted Smallwood’s numerical account and said that only 300 Tories were present. The number cannot be definitively known, but it was likely closer to 400 just before the battle.[10]

Major Cloyd, commanding the Montgomery County Militia of Virginia, arrived first at the Ford and engaged the Tories, catching them by surprise as they moved out of the Ford and onto the Mulberry Road. Colonel Peasley, sent by Sumner from Salisbury, and Colonel Williams, resident of the Ford, had mustered a force of roughly two-hundred Yadkin militia in an attempt to curtail the Tory advance. It was around 10am when Peasley and Williams “were within almost one and a half miles of Shallowford. They heard a foray advanced up with all possible speed, thinking our light infantry engaged.” Peasley and Williams advanced upon Cloyd’s men and arrived in the waning heat of battle, helping to drive the Tories back and dispersing them greatly. “The 300 loyalists prepared to cross the river, not suspecting any opposition. The conflict was short, hard and decisive. The Tories, badly beaten, fled and scattered.”[11] The result was the death of only one Patriot, Capt. Henry Francis. As oral tradition tells, he was shot through the head with his son, John, at his side. Likewise, the Tories lost fourteen wounded and had three taken prisoner.[12]

As the skirmish concluded and the Tories dispersed, the evening crept in overhead of Cornwallis’s baggage train and Tarleton’s legion, as they made their way south of Charlotte. The King’s Mountain defeat had robbed the British of Patrick Ferguson and his men and the battle at the Shallow Ford had driven a large body of militia into obscurity and away from the British force. Estimable victories had been suppressed and the British now stood alone in the Carolina’s. Loyalists certainly remained at large, yet a cold wind blew at the back of British ambition.

Five days later, the British having evacuated Charlotte and the Surry Tories having dispersed, Colonel Armstrong published a pardon written from the Shallow Ford on October 19: “I hereby give this public notice, requesting and commanding all those deluded people in the Cot’y of Surry who have been concerned in the late insurrection and taken up arms against their Country, in open violation of the laws thereof, to come to Richmond [the county seat] on or before the first date of November Next and Deliver up their Arms.”[13] Colonel Armstrong’s offer of parole sought to quell and make peace with the once-marauding Tory militia in his county. It also offered them parole in an attempt to remove their ability to make war and terror again.

The long march of pillaging and burning by the Surry County militia lasted several weeks; and although sequestered to Surry County and the battle at the Ford, the impact reverberated throughout the South. Terror in the backcountry meant homes were burned and robbed, sheriffs shot, and a general and dangerous raucous created, and yet it was cut short in a skirmish at the Shallow Ford. More than the halt of four hundred Tories, it sent a resounding message aimed at British morale that war in the South would not be easily won. It pressed the resolve of Cornwallis and extended as far as the British command. It would take not just ambition and political articulation, but true strength and resiliency to subdue the southern colonies, especially the Carolinas, still the backcountry of North Carolina continued to be characterized by this civil war. Conflict across and within counties between Whig and Tory arose constantly and exposed its perpetual presence.

On Wednesday, October 18, 1780, the North Carolina Board of War sent a letter to the delegates of North Carolina. Both the defeat of Patrick Ferguson at the Battle of King’s Mountain on October 7, and the routing of Tories at the Shallow Ford on October 14, were given credit for, “Lord Cornwallis’s retreat from Charlotte.”[14] Although thought of at the time as a significant skirmish that kept Cornwallis’s numbers from growing and that ended the Surry County militia’s destruction in the backcountry, the Battle of the Shallow Ford has since been overshadowed by greater conflicts and personalities. Because it was fought by militia and had no famous participants, the skirmish on the morning of October 14 remains a blip on the historical record. Yet, the skirmish at Shallow Ford was undeniably important to both the British and Patriots of the time. As 1780 waned, the position of the Patriots in the South looked dire, yet the rout of Tories at both King’s Mountain and the Shallow Ford greatly altered the landscape of the southern war. It placed a newly minted Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene, arriving on the backs of these conflicts in Charlotte in December, on surer footing. The Patriots were not ruined, but still remained in the fight. The tide of the war in the South was primed, under the right command, for a turn in favor of the rebellion.

[1]Horatio Gates to Thomas Jefferson, September 9, 1780, Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-03-02-0718; original source: The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 3, 18 June 1779-30 September 1780, ed. Julian P. Boyd (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1951), 620-621.

[2]Jethro Sumner to Gates, October 4, 1780, Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, Documenting the American South, docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr14-0565, 14: 667-668.

[3]Martin Armstrong to Jethro Sumner, October 7, 1780,” Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, Documenting the American South, docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr14-0576, 14: 675-676.

[5]Frank Salter, “Wright, Gideon,” ncpedia.org, www.ncpedia.org/biography/wright-gideon.

[6]Armstrong to Sumner, October 7, 1780.

[7]Sumner to Gates, October 13, 1780,” Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, Documenting the American South, docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr14-0598, 14: 692-693.

[8]Joseph Williams to Richard Casewell, June 4, 1779, Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, Documenting the American South, docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr14-0118, 14: 109-110.

[9]William Smallwood to Gates, October 16, 1780,” Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, Documenting the American South, docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr14-0607, 14: 698-699.

[10]John Peasley to Sumner, 1780, Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, Documenting the American South, docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr14-0743, 14: 790.

[11]Pat Alderman, Pat. One Heroic Hour at King’s Mountain (United States: Overmountain Press, 1990), 130.

[12]John Peasley to Sumner, 1780.

[13]Advertisement by Martin Armstrong Concerning a Pardon for Loyalist in Surry County, October 1780, Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, Documenting the American South, docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr15-0741, 15: 124.

[14]Minutes of the North Carolina Board of War North Carolina. Board of War September 14, 1780 – January 30, 1781, Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, Documenting the American South, docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr14-0396, 14: 429.

4 Comments

Thank you so very much for your preservation of this valuable, and interesting History.

I lived in Salisbury for 13 years, and the people there were top shelf.

It is interesting that folks not actually in Surry County made claims that the Tories were burning and pillaging, while those present only related three instances. Nothing happened in September, other than Col. Bryan left with close to 800 Loyalists. The first report of a raid came from the October 3rd raid on Richmond Courthouse by Gideon Wright’s men. That resulted in the killing of Sheriff Hudspeth and a few rebel militia taken prisoner and then paroled. A few days later, Wright attacked Captain Shephard’s home. Then on Oct 8, Wright scattered Captain Stanly’s Company at Richmond Courthouse. It seems Wright was going after men who had been viciously murdering Loyalists for the past three years in the company of men like Benjamin Cleveland. The rebels were even beating up Moravian men and women.

Do you have any other information about the sheriff who was killed? I’ve seen his name as Hedgspeth as well. The Surry County Genealogical Society is asking about him.

A couple more bits of food for thought:

1. Gideon Wright was living on the Yadkin River by 1755. He was paid as a Captain in the Rowan County Militia in April, 1760. Has anyone found any service records for him in NY?

2. The Battle did not occur at the Shallow Ford. It was almost 1 mile west of the ford. According to a number of accounts, the Tories were mounted and strung out in a line that stretched from the ford to the crest of the hill overlooking Battle Branch. As the Tories were moving down the hill on Mulberry Fields Road, Major Cloyd’s men opened fire. Some of the Tories turned and fled back across the river and some dismounted and formed a firing line. Outnumbered, they were quickly dispersed, wounded, and killed. One Black Loyalist named Ball Turner continued firing on the Rebel militia. He was eventually killed, “his body riddled with bullits.” (Draper Manuscripts C:8:43).

Joseph Williams came up AFTER the battle and found the militia were smashing the skulls of the wounded Tories. He managed to save at least one wounded man named Skidmore.

3. Now, nearly everyone claims the Tories were headed to join Cornwallis. The only problem is, they were headed the wrong direction. The Tories were moving northwest along the Mulberry Fields Road toward an area referred to as “Tory Country”. This was essentially the Mitchell River drainage. If they wanted to head south toward Cornwallis, they would have turned right at the intersection and taken either the Great Wagon Road to Salisbury, of the Georgia Road due south. Both paths would have put them well east of troops returning from King’s Mountain.