Immediately following the taking of Fort Ticonderoga by Ethan Allen and the Green Mountain Boys in early May 1775, Capt. John Visscher raised a company of seventy-five men, at the request of the Albany County (New York) Committee of Safety, Correspondence, and Protection. His company was ordered to proceed to that post and defend it for the safety of the Province. This was the first company raised for that purpose but it soon became part of the nucleus of the new 2nd New York Provincial Battalion in which Visscher was commissioned the highest rated captain July 11, 1775. Visscher and his men would go on to participate at the reduction of St. Jean and Montreal. While at Longueil, Visscher was second in command to Lt. Col. Seth Warner of the Green Mountain Boys when the British attacked in an attempt relieve St. Jean.[1]

By November 1775, when their field officers left for a new unnumbered battalion, Captain Visscher was the highest ranking officer left in the 2nd New York. All the companies in the regiment were woefully undersized through attrition, so it was decided to beef up Visscher’s company and send it to Quebec with Brig. Gen. Richard Montgomery’s advance force.[2]

To this end, a transcribed muster roll of Capt. Elisha Benedict’s company of the 2nd New York, stationed at Fort Chambly, notes that twelve men were “On command at Quebec” and were presumably assigned to Visscher’s company. Two of the men were Cpl. Moses Evans and Pvt. Daniel Bean.[3]

Captain Benedict’s company was regionally recruited, in July 1775, out of New York’s Albany and Cumberland Counties. (The former extended easterly into the lower southwestern portion of the future state of Vermont and the latter made up the southeastern portion.) The 1st lieutenant was William McCune and Alexander Brink was the 2nd lieutenant.[4] Lieutenant Brink recruited both Evans and Bean in the spring of 1775. Bean joined up at Albany, New York, while Evans was recruited before marching there with the company. Leaving for points north, they would be together for the remainder of 1775. Their paths would soon branch in different and exciting directions.

Corporal Evans’s rather detailed Federal pension application explains that he was a resident of Cortland in the Hampshire Grants, at the time of his enlistment and:

… that after his enlistment was marched to Albany N.Y. where the Regt was mustered — Maj. Gansevoort took the command, the Col. being Muster Master & the Lt. Col. having died. And marched to Crown Point then to Isle Aux Noix … That from Isle Aux Noix he was detached into a company of rangers under Major [John] Brown and was in the engagement under his command at the taking of Fort Chamblee which was in the fore part of October. After the capitulation of St. Johns they marched to Montreal which surrendered on the 13 Nov. That at Montreal Captain Fisher of Col. Van Schaick’s Regt and three other Capts the oldest in the Regiment were with their companies detatched to march with Gen. Montgomery to Quebec ― that Capt Fisher’s Co. not being full men were detatched from the Cos of Captain Benedict and Capt Graham to make it a full Co and that he was detatched into said Co as an orderly sergeant ― that they marched then on to Quebec to unite with the forces under Col Arnold in besieging that place ― that he was present under the immediate command of General Montgomery in his assault upon that place Dec.31.1775 when the General was killed and himself wounded … .[5]

Many years after the assault on Quebec, Col. Donald Campbell, the default commander of the assault force following the initial blast that killed General Montgomery, reported on what happened next:

Captn. Vischer, of the 2d. Yorkers & Benschoten of the 3d & some others then Came up; After repeated enquirey for the Carpenters, Guides, &c. and finding the rear not yet in the Barrier, they being tired & wore out I desired Vischer to get some men to remove the groaning Wounded & enable them to Crawle off.[6]

The presumption here is that Captain Visscher used his own company to remove the wounded, which explains when Evans might have been wounded. Pvt. John Rose, one of the many transferees into Visscher’s rebuilt company, was, by his own account, wounded in the arm during the assault.[7]

Like Moses Evans, Daniel Bean was one of the twelve men from Benedict’s company put on command with Capt. Visscher’s under-strength company. In a far less detailed account, Bean explained that:

… I joined the regiment at Albany, marched from there to Ticonderoga, then to Canada, was present at the taking of St. Johns, Chamblee & Montreal … and went down to Quebec with Genl. Montgomery – I was present at the Storming of Quebec & near the General when he was killed. I staid with the army all winter until may and then my time was out & I was then discharged by Capt. Benedict at Chamblee in Canada.[8]

Luckily, Bean seemed to have come out of the assault unscathed, as he did not mention receiving any wounds.[9]

Where Bean’s story is very specific on most points of transition, Evans’s skips over them in favor of excessive details at key points. For example: after the fall of Fort Chambly, there is no information as to whether he returned to his old company before or after he returned to Montreal. He clearly did go back, as he was sent on command to Quebec with the others. His story then has another gap when there is no mention of him returning to his company after the Quebec assault, or if he was hospitalized as a result of his being wounded.[10]

While he was still in Canada, in the spring of 1776, Evans took over the command of a newly arrived company of volunteers from Charlestown, New Hampshire, under Brig. Gen. David Wooster’s orders. They had lost their commander and Wooster felt the fresh troops could use his experience. Evans continued with this unit through the army’s retreat from Canada, including the Battle at Three Rivers (Trois Rivieres), after which the unit disbanded.[11]

Evans was a soldier at Fort Ticonderoga when it was evacuated by Maj. Gen. Arthur St. Clair’s forces. He also fought at the Battle of Bennington under “Colonel Warner,” presumably Seth Warner, commander of his own unnumbered continental regiment. It is not clear if Evans enlisted in this unit or, more than likely, just served under its commander. Following that, Evans went on to explain that:

… he was subsequently in 1777 at Mount Defiance under the Command of Major Brown and was with him at the taking of Portash landing and of the bateaux belonging to the British who at the time had a sentinel garrison occupying one of the Islands in Lake George which said Brown aimed to take, but by the fortunes of war that a part of said Brown’s men were captured and that the said Evans being sick was among the captives – That he was carried thence to Ticonderoga and into hospital at Mt. Independence where he remained a month until The Reddo came and took about two hundred and fifty prisoners and sailed for St. Johns – Went from St. Johns to Chamblee then to Montreal thence to River Sorell thence to Quebec – And thence to Isle of Orleans when he and four other prisoners made their escape and came to the American Settlements near the headwaters of Kennebec River – That they started from the Isle of Orleans the 13th May 1778 and were out twenty three and a half days before they came to the American Settlements and in the time endured many privations and hardships … .[12]

This action described by Evans was part of a September 1777 counter attack under Maj. Gen. Benjamin Lincoln’s over all command, waged on Mount Defiance, Mount Independence, Fort Ticonderoga, and the portage connecting Lakes George and Champlain. Evans served under Colonel (which he remembered as his earlier rank of major) John Brown.

Colloquially known as Brown’s Raid, the expedition consisted of companies from Brown’s militia regiments, Whitcomb’s Rangers, and elements from the regiments of Colonel Warner, Colonel Herrick, Colonel Marsh, Colonel Johnson, Colonel Woodbridge and Colonel Cushing.[13] After taking the portage (not “Potash”) landing place on the morning of September 18, Brown’s men rushed down into the LeChute river valley and captured hundreds of British prisoners, destroyed supplies, and seized a large number of gun boats, bateaus, and cannons. They also took Mount Defiance, but after making it to the old French lines at Ticonderoga, they were unable to take the fort.[14]

Brown then focused his next attack on Diamond Island, which Evans refers to above as “one of the Islands in Lake George,” on September 24, but was repulsed before making it ashore. Colonel Brown reported to Maj. Gen. Benjamin Lincoln that he had two men killed and two others mortally wounded who he was obliged to leave to the mercy of some local inhabitants he had earlier taken prisoner. He makes no mention of any sick.[15] However, a German officer noted in his journal that “The enemy had also left their own sick and wounded behind at Lake George.”[16]

“The Reddo” refers to large beefed up five-sided raft-like bateau called radeau (singular) or radeaux (plural). Since it is unlikely that one radeau could transport over two hundred prisoners and their guards, Evans probably meant radeaux.

After making his way home, on October 15, 1778, Evans had the unabashed gall to petition the General Assembly of the separate and independent state of Vermont for his losses. He included some more contemporary specifics as to what happened to him on his journey. They are clearly more detailed than the aged memories expressed in his pension application:

That whereas your Petitioner was taken prisoner, by the British Troops at Diamond Island, on the Fifth day of October 1777, and from thence transported to the Isle of Orleans below Quebec, and thence detained until 13th of May 1778, at which time he found means to make his escape, and was necessitated to go thro’ almost inexpressible hardships, both by fatigue & huger through the unknown desert to Kennebec and from thence home, where he arrived 20th of June last, and besides the hardships of imprisonment, March &c your Petitioner lost one Gun price £4.10 One Blanket, with sundry other articles to almost £8. for which time, losses, expense &c your Petitioner had not recd any other than Continental pay.

These are there to pray your Honors to grant your Petitioner such allowance as in your wisdom shall think proper.[17]

Within a day, Evans’s petition was, surprisingly, approved and the state treasurer paid him a lump sum of twenty-nine pounds, one shilling, and four pence for his time, gun, blanket, and other sundries.[18]

Meanwhile, just prior to the Hampshire grants declaring themselves a separate and independent state, Daniel Bean had joined the Continental Army again. At Windham (part of New York’s soon-to-be former Cumberland County), he enlisted in Capt. William McCune’s company of Col. Seth Warner‘s (unnumbered) Continental Regiment for three years. The company then marched to Fort Ticonderoga, where on July 5, 1777, Maj. Gen. Arthur St. Clair ordered the fort’s defenders to evacuate and move south to make a stand. Bean described that he:

… was with Col. Warner in the fight at Hubbardton and the battle of Bennington, where I was taken prisoner by the enemy who kept me about ten days & I then made my escape & joined my company & my regiment again – I was present at the taking of Gen. Burgoyne, & in the Spring of 1778 we marched to Fort Edward, to look out on the frontier, where we lay all summer and the next winter, & in the Spring of 1779 we marched to Fort George at the Head of Lake George; …[19]

At this point, one would obviously speculate if these two veterans ever met again at Fort Ticonderoga or on the field at Bennington (which was really Walloomsac, New York), in some capacity. Sadly, we may never know.

About two years later, an official report indicated what next happened to Daniel Bean:

St. Johns, 20th July, 1779.

List of a party of Col. Warner’s regiment, who left Fort George to gather huckleberries on Fourteen Mile Island, and were killed, wounded, or taken prisoners the 15th instant by a scout of twenty-four Indians and three white men sent out by Colonel Claus.

|

Killed |

Prisoners |

|

Major Wait Hopkins |

Capt. Gideon Brownson, also wounded |

|

Sergt. Benj. Laraby |

” Simeon Smith |

|

Corp. Robt. Quackenbush |

Lieut. Michael Dunning |

|

Private Soldier Robt.Smith |

Sergt. [David] Curtis, also wounded |

|

” Sam1 Godsel |

Private Soldier Daniel Bean |

|

” [John] Lee |

“ John Whitely |

|

” [Josiah] Bump |

“ [Richard] Freeman |

|

Women, Mrs. Quackenbush |

A boy 9 years old, S. Thomas |

|

Mrs. Thomas |

|

A Mrs. Scott and one child were wounded and left with another child on the island. The Indians stripped and scalped the men that were killed, but did not offer any violence to the women after the first fire.[20]

The size of the party has not been determined, but presumably the report includes everyone in it since it is unlikely anyone could have escaped the island after the ambush. One has to wonder why such a large number of officers, non-commissioned officers, and family members would venture out of a relatively secure area like Fort George to gather huckleberries.

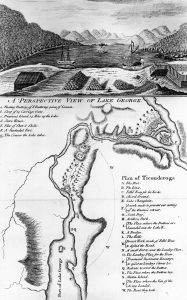

According to many period maps, Fourteen Mile Island appears closer to twelve miles from the head of Lake George at the entrance to the Narrows. It comprises an area of only about twelve acres of land and mossy rock that is covered with a grove of typical New York trees such as oak, chestnut, and pine. More importantly, the island has an uninterrupted view of the lake to the south.

Bean’s deposition, in his Federal pension application file, describes the excursion to Fourteen Mile Island as a “scouting party” and does not mention the foraging at all. He clearly states that the Indians were Mohawks and that he was wounded in the attack, which was not included in the above report. Not accounting for the civilians, Bean further explains that seven were killed and that he and six others were carried to Montreal and then delivered to the English. From there, he, not mentioning the other six, was sent to Quebec, where he was a prisoner for two months. At this point, he made his escape (he does not explain how) through the woods to his home in Salisbury, New Hampshire. It being October 1779, he “understood that the Regiment of Col. Warner to which I belonged was broken up.”[21]

In the meantime, Bean’s wife, Phoebe, had written the Treasurer of the State of Vermont for his outstanding pay:

… for his services as a Corporal in Col. Seth Warner’s Regiment, he being supposed to be now (if living) in the sea-service of his Britanic Majesty in Europe, or other foreign quarter of the word, into which service he was impressed, in the City of Cork in Ireland, while a prisoner of War … .[22]

Though understandable, it is clear she was reacting to some unfounded information. Eventually, it worked out for her. Not only had her husband returned, but on February 13, 1784, the Vermont Treasurer’s Office ordered payment of “forty pounds two shillings and nine pence lawful money, in full for the depreciation & interest” due Daniel Bean for his service in Warner’s regiment.[23]

Beyond issues regarding his wife’s concerns, the muster rolls of Captain McClure’s company dated from September 1776 thru June 1779 provide confirmation and some details that enhance Bean’s story. They show he enlisted with the company on December 4, 1776, as a private soldier, and was taken prisoner the first time in July 1777. He returned from captivity on January 14, 1778, and was promoted to the rank of corporal. A year later, on January 12, 1779, he was reduced in rank (for no specified reason) to private; the rank he was when he was captured on Fourteen Mile Island. In referring to him as a corporal, Phoebe Bean must not have known of his reduction in rank.[24]

Where Bean had ended his service, Evans kept on going. He received a commission as lieutenant of a company of State troops in the vicinity of Arlington, Pittsford, and Rutland, Vermont, between the years of 1781 and 1783.[25]

Thomas Tolman, a former lieutenant with Warner’s Regiment and a federal pensioner, wrote an affidavit on January 20, 1836, where he explained that he knew Evans “… to be a Lieutenant in the said years of 1781, 2, & 3 in a regiment in the Troops of the said State, during the said years, which Troops were discharged at about the time of the disbanding of the main Army.” He explained he was the paymaster for these troops, but had lost all his old papers and could not provide any exact dates of Evans’s service. Tolman also wrote that “Moses Evans is of a highly established reputation & character, as a man of honor, & pure morals.”[26]

A year later, in a subsequent affidavit, Tolman, clarified that Evans served at least two years as a lieutenant with those troops and was stationed at Fort Pittsford in Vermont. Tolman also wrote he was paymaster with the same troops from 1781 to 1782 and has also been a paymaster when he was with Warner’s.[27]

Evans and Bean were both pensioners for their service in the revolution. Each would receive a pension of $8.00 per month from the federal government, under the pension act of March 18, 1818. Though their financial situations were quite similar, how and for what they earned this pension could not have more different.

Evans did not file until 1828. He was eighty-seven years old and living in Lyndon, Caledonia County, in north eastern Vermont when he filed, making him nearly thirty-four years old when he joined the 2nd New York. A schedule of his personal items at the time of his application showed him owning one cow, a table with three old chairs, three old chests, an axe, a hoe, eight milk pails, and the like amounting to $32.50. Considering his financial situation and and lack of a family, Evans really needed financial support. Unfortunately his delay in filing probably cost him about $960.00.[28]

Daniel Bean, in his pension deposition of April 1818, claimed to be infirm, destitute of property, and was living by what manual labor he could do. Being in reduced circumstances he was in need of assistance from his country for support. He owned a tea kettle, a table, four chairs, some crockery, utensils, a fire shovel and tongs, and some other items that totaled about $10.00; he also owed $18.00 or so. He was sixty-two years old and living in Salisbury, in south central New Hampshire, at the time of his deposition. This would have put him at about nineteen years old when he first enlisted in 1775.[29]

By the time of his pension application, Bean had remarried; what had become of his first wife, Phoebe, is not known. He had married Delley (or Dilly), nineteen years younger than he, in 1817 and they had two children.[30]

Despite his long service record, Evans, according to law, was only granted his enlisted man’s pension for his one year of Continental service with the 2nd New York. Bean received his pension for his three years service in Warner’s regiment. His first year of service, in the 2nd New York and the failed assault on Quebec, was not considered.[31]

In an effort to get more pension money for his service as an officer, Evans submitted a second claim under the Pension Act of June 7, 1832. This act allowed the veterans to claim their militia and state troop service. So, this claim was far more involved than his earlier one and was the primary source for his narrative here. However, the Federal Pension Office did not seem to agree.

Evans’s claim for service as captain of the company of rangers in 1776 could not be admitted because General Wooster had no authority for granting commissions and there was no formal commission to refute that claim. The pension office also stated that his service with the 2nd New York was more in accordance with known history of the period and was directly opposed to his claim of service as a captain. This opposition was caused by a timeline overlap due to Evans (or his attorney) making the simple mistake of claiming, in 1828, his service in the 2nd New York was in 1776, not the correct 1775, which he fixed in 1836. He could not claim being a captain in 1776, when he had already been approved for serving as an enlisted man for the same year on the previous claim. [32]

Despite his claims being supported by depositions from Tolman, they rejected Evans’s claim of service with the Vermont State Troops in the 1780s as a lieutenant as there was no satisfactory evidence that he ever served a day under his commission.[33] Regrettably, Evans did not know there were several enlisted men and widows who had submitted claims under the 1832 pension act that claimed to have served during the same period under Captain Safford and Lieutenants Moses Evans and Zebulon Lyons in an unspecified regiment in the Vermont State Troops.[34]

Evans and Bean would settle down about a hundred miles from each other near the Vermont and New Hampshire border. Separated by about fifteen years in age, after beginning their service together in the Continental Army, they would travel similar, yet very different paths. Ultimately, their timelines would each end up in very similar circumstances.

[1] Petition of Lt. Col. John Visscher to the Committee for Arrangement of Officers of the State of New York, January 1777, Calendar of Historical Manuscripts Relating to the War of the Revolution, in the Office of the Secretary of State (Albany, NY: Weed, Parsons and Company, 1898), 2: 21-22. Berthold Fernow, ed., Documents Relating to the Colonial History of the State of New York (Albany, NY: Weed, Parsons and Co., 1853–1887), 15:253, 528, & 540.

[2] Entry for November 28, 1775, “Journal of Col. Rudolphus Ritzema of the First New York Regiment, August 8, 1775 to March 30, 1776,” Magazine of American History With Notes and Queries, 1(1877), 98-107. Ritzema only cites one 2nd New York company went to Quebec with General Montgomery, so it had to have been Visscher’s.

[3] A Muster Roll of Captain Elisha Benedict’s Company of the Second Regiment of New York Troops now in the Service of the United Colonies under the Command of Colo Goose Van Schaick now Stationed at Chambly Fort Dated this 31 Day of January 1776, Revolutionary War Rolls 1775–1783 (National Archives Microfilm Publications, M246, 138 rolls), War Department Collection of Revolutionary War Records, Record Group 93, National Archives Building, Washington, D.C. (NAB), Roll 67, Jacket 19. This roll is a pen and ink transcript, not the original document. No known muster roll exists for Capt. John Visscher’s company.

[4] Fernow, Documents, 15: 528. Elisha Benedict to Peter Van Brugh Livingston, President, New York Provincial Congress, July 14, 1775, Peter Force, ed., American Archives (Washington, D.C., 1837-53), 4th Series, 2:1796. New York Committee of Safety to Elisha Benedict, July 14, 1775, Force, American Archives, 4th Series, 2:1796-1797.

[5] Deposition of Moses Evans, April 20, 1836, S.38685, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty Land Warrant Application Files, 1800-1900, Record Group 15, National Archives Building, Washington, DC (National Archives Microfilm Publication M804, Roll 940), hereafter cited as Pensions. An orderly sergeant was the early-war equivalent of a continental army first sergeant, which was the top sergeant in an infantry company. It should also be noted that Evans’s statement about his regiment’s commanders contains an obvious mistake or memory lapse, as Lt. Col. Peter Yates was not dead.

[6] Col. Donald Campbell to Robert R. Livingston, March 28, 1776, Livingston Papers, Transcribed Letter Book, Franklin Delano Roosevelt Library, 1937, 3-4.

[7] Deposition of John Rose, September 28, 1830, S.42870, Pensions (Roll 1562).

[8] Deposition of Daniel Bean, April 29, 1818, S.45522, Pensions (Roll 188).

[9] Ibid.

[10] Deposition of Daniel Eastwood, October 15, 1832, S.15108, Pensions (Roll 889). One of the twelve transfers, along with Evans and Bean, describes “… that about the 1st of May 1776 he returned from Quebec and joined his old Company under Captn Benedict as aforesaid near the City of Albany … .” He explained further that the company, on an extended enlistment totaling eighteen months, traveled out to Johnstown, New York, and then went back east to Ballston, New York, where they were discharged. This account of the return from Canada is completely different than either Evans or Bean. Lacking anything to the contrary, it appears best to treat each veteran’s description individually.

[11] Deposition of Moses Evans, April 20, 1836, S.38685, Pensions (Roll 940).

[12] Ibid.

[13] Colonel Brown to General Lincoln, September 14, 1777, in The New England Historical and Genealogical Register (Boston, MA: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 1920), 74, 284–285, from notes provided by the staff of the Fort Ticonderoga Museum.

[14] Colonel Brown to General Lincoln, September 18, 1777, in Genealogical Register, 74, 285–286. Portage Landing is located on the Vermont side at the northern end of Lake George. It is likely that the attorney taking Evans’s deposition misunderstood “portage” to be “potash.”

[15] Colonel Brown to General Lincoln, September 20, 1777, in Genealogical Register, 74, 289-290.

[16] Entry for September 23, 1777, Mary C. Lynn, ed., The American Revolution, Garrison Life in French Canada and New York: Journal of an Officer in the Prinz Friedrich Regiment, 1776-1783, translated by Helga Doblin (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1993), 81, from notes provided by the staff of the Fort Ticonderoga Museum.

[17] Petition of Moses Evans to the General Assembly of the State of Vermont, October 16, 1778, John B. Goodrich, ed., Rolls of the Soldiers in the Revolutionary War, 1775 to 1783 (Rutland, VT: The Tuttle Company, 1904), 694-695. Entry for Moses Evans, Frances B. Heitman, Historical Register of Officers of the Continental Army During the War of the Revolution, April, 1775, to December, 1783, Reprint of the New, Revised, and Enlarged Edition of 1914, With Addenda by Robert H. Kelby, 1932 (Baltimore MD: Genealogical Publishing Company, 1982), 219. Heitman’s entry for Evans appears to list the documents from Goodrich for his date of capture and escape.

[18] Goodrich, Rolls, 695.

[19] Deposition of Daniel Bean, April 29, 1818, S.45522, Pensions (Roll 188). William McCune was Bean’s 1st lieutenant when he was in the 2nd New York in 1775. The inhabitants of the Hampshire grants formed themselves into a separate and independent state, or government on or about January 15, 1777.

[20] Goodrich, Rolls, 836. Entries for Michael Dunning and Wait Hopkins, Historical Register of Officers, 207 & 300. Here it is noted that both Lieutenant Dunning (captured) and Major Hopkins (killed) were near Stony Point, New York at this time. Since no member of Warner’s Regiment would have been that far south, these assumptions were clearly an incorrect extrapolation based on the date of the incident on Fourteen Mile Island. The names in brackets are based on those found on existing muster rolls of Warner’s regiment microfilmed by the National Archives.

[21] Deposition of Daniel Bean, April 29, 1818, S.45522, Pensions (Roll 188).

[22] Phoebe Bean to Ira Allen, Treasurer of the State of Vermont, undated, Goodrich, Rolls, 769.

[23] Goodrich, Rolls, 769-770.

[24] Muster rolls for Capt. William McCune’s Company, in a Battalion of Forces in the Service of the United States Commanded by Colonel Seth Warner, September 16, 1776 – February 1779, Revolutionary War Rolls 1775–1783, Roll 134, Jacket 230-4.

[25] Deposition of Moses Evans, April 20, 1836, S.38685, Pensions (Roll 940).

[26] Affidavit by Thomas Tolman, January 20, 1836, S.38685, Pensions (Roll 940). Historical Register of Officers, 545, erroneously lists Tollman as having died on April 19, 1809.

[27] Affidavit by Thomas Tolman, January 21, 1837, S.38685, Pensions (Roll 940).

[28] Deposition of Moses Evans, March 7, 1828, S.38685, Pensions (Roll 940).

[29] Deposition of Daniel Bean, April 29, 1818, Exhibit of his property submitted to the Justices of the Court of Common Pleas, July 11, 1820, S.45522, Pensions (Roll 188). The Pension List of 1820, U.S. War Department, (Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Publishing Co, 1991), with new index, originally published as Letter from the Secretary of War, Transmitting a Report of the Names, Rank, and Line, of Every Person Placed on the Pension List, in Pursuance of the Act of 18th March, 1818, &c., January 20, 1820, (Washington, DC: Gales & Seaton, 1820), 9.

[30] Declaration to the Justices of the Court of Common Pleas, July 11, 1820, S.45522, Pensions (Roll 188). Salisbury, New Hampshire Marriage Records, Daniel Bean to Dilly Sanborn, June 1, 1817, http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~nhcsalis/marriages.htm. This record is annotated that Daniel Bean & Dilly Sanborn are listed in a second place as marrying June 1, 1815.

[31] Certificate of Pension issued to Moses Evans, [tear in document] 1828, S.38685, Pensions (Roll 940). Certificate of Pension issued to Daniel Bean, July 3, 1818, S.45522, Pensions (Roll 188). These two men were lucky they received a pension at all. According to the Act of March 18, 1818, provided they served for at least nine months in the continental army, surviving veterans in financial need were able to file a federal pension application. However, there was some inconsistency in determining if an applicant’s service in the New York regiments of 1775 counted as being in the Continental Army. Even though their officers were commissioned by the Continental Congress, it was often unjustly determined by the bureaucrats that the veteran had only served with the state troops or the militia, and not the Continentals, so their application for benefits was denied. Yet, others under similar circumstances qualified for benefits. For some examples of other former 2nd New Yorkers in this situation see depositions of Andrew Fine, S.43561, Pensions (Roll 975), James Gray, S.43645 (Roll 1114), John Hogeboom, S.13457 (Roll 1818), Malcart Vanderpool, S.42586 (Roll 2443), Matthew Van Der Pool, S.42594 (Roll 2443). Entries for Andrew Fine and John Hogeboom are annotated “Not continental & struck from roll” in The Pension List of 1820, 381 & 394.

[32] Letter from J. L. Edwards to George C. Cahorn, May 17, 1836, S.38685, Pensions (Roll 940).

[33] Ibid.

[34] For details see John Cady, W.3511, Pensions (Roll 446), John Evans, S.10638, (Roll 940), William Strong, W.25132 (Roll 2315). Deposition of former company commander, Jesse Stafford, August 20, 1832, in William Strong, W.25132, Pensions (Roll 2315).

8 Comments

Phil:

Another outstanding job! Good information about real 2nd Yorkers. As usual, the research is thorough. Hope to see more articles about the 2nd N. York soon!

Thank you Joe. There a “few more” in train, but nothing in the JAR queue yet. These will not be as involved as this one ended up being… but, then again, I have said that before.

Good job Phil! Fascinating details about real people. So many old soldiers ended up in poverty. What happened to their promised land grants, I wonder? My best, phil giffin

Phil,

Funny you should ask that question as I am deep into the legal background of Vermont’s pre-RevWar creation years and which is inextricably tied to the disputed Grants (this has involved a lot of research in Vermont and NY archives, court records, etc.)

There are a couple of types of “grants” involved here: 1) those NY lands sold by NH Governor Benning Wentworth beginning in 1749 to speculators who then sold their interests to settlers that went on to cause so much friction with NY and the Continental Congress; and,2) those coming out of the Seven Years’ Wars made in 1765 by NY authorities to retired British soldiers, officers, etc. It was the overlapping of the latter grants over the former that caused so much of the ensuing harm.

As far as lands granted by the Continental Congress for service during the Rev War goes, that would have amounted to nil as far as the Grants region goes. Loyalists from there ended up going to Canada or being displaced to other NY lands. The area was a hotbed of intrigue with deserters flocking in from the Continental Army, confiscations of tory lands being sold to the likes of Ethan Allen’s clan and cronies, banishments of loyalists, and draconian medieval punishments meted out to those not towing the Allen line that included whippings, brandings, nailing ears to posts and cutting them off. The Continental Congress hated the whole thing and could do nothing to stop it, but which finally ended in 1791 with statehood.

It was a truly sordid affair and some of it will be included in a forthcoming book I am working on.

Gary, your book-in-progress sounds intriguing and I’ll watch for it. I know generally of the New Hampshire Grants mess but would really like to get into the details.

Thanks, Nancy. I dig into some of this in a masters thesis I did last year on the symbolic aspects of Vermont’s 1777 Constitution, its vaunted provisions disproven by these egregious actions (if interested, get my email address from the editors and I can send it to you). The book is in progress, collaborating with two other Vermont historians, with my concentration being on the legal aspects surrounding the pre-war period. Lots of new information coming out and we think it will be enlightening to students of those times. Stay tuned.

With regard to the economic condition of veterans and their land grants, there are a couple other considerations beyond those mentioned by Gary. For one, I’d bet that some gave a goodly portion of their possessions to their kids or kin or found other ways to make themselves appear more destitute so that they would qualify for a pension. I haven’t done any research on that topic but it seems terribly logical given human nature.

As far as state and Congressional land grants go, lots of men who wanted/needed immediate cash sold their rights to the grants to others for far less than their value. The veteran never saw the land granted to them. The same happened with certificates for depreciation money intended to make up for the inflationary impact on their pay. I have done some research on this topic and it happened far more often that one might expect.

Phil, no comment on the land grants, as I have not made a major study there. However, I can offer that when you are reading the Federal pension application files, those on the 1813 list are wounded and injured men, but on the 1820 list you are looking at men who were, by definition, destitute. So, these files give the impression of all of the veterans being on hard times. Add to the fact that you are getting farther and farther down the timeline. Some of these potential pensioners had gotten so old they were not able to perform basic skills, plus they lacked the medical marvels we have today. In truth, I am amazed that so many were still alive in 1820 and beyond.

The numbers are very interesting as well. For the 2nd New York, of 1775, of the original 758 officers and men, lacking all of the muster rolls, I have only found aboout 580 names. Of those, only 168 have detailed information of their service in the form of pension applications, biographies, cross-referrences, etc. I have determined that only about 70 of those served in the Continental Army beyond the spring of 1776, which is about 10% of the original members. So, this alone is a good indicator of how few men were even eligible for a pension based on their length of service.