This article supplements one of mine that appeared in the Journal of the American Revolutionin November 2016.[1] Based partly on The Cornwallis Papers,[2] it provides a wide-ranging set of reappraisals compartmentalised under the sub-headings below.

James Paterson

Paterson, as he signed his surname, had been appointed Lt. Colonel of the 63rd Regiment on June 15, 1763. By 1780 a brigadier general, he accompanied Sir Henry Clinton, the British Commander-in Chief, to Georgia on the Charlestown, South Carolina, campaign and was put in command of a force that was to make a diversion from Savannah towards Augusta, but these orders were countermanded. Instead, he was in March summoned to South Carolina to reinforce Clinton with some 1,500 men. After the capitulation of Charlestown he was appointed by Clinton to be Commandant of the town, but overwhelmed by the confusion, perplexity and civil nature of the business, he was not up to the job, finding himself “embarked on a situation out of the line of my profession.” Fortunately for Lt. Gen. Charles Lord Cornwallis, who was left to command in the South, Paterson fell ill and on July 18, 1780 was conveniently shipped to New York for the recovery of his health, being replaced by Lt. Col. Nisbet Balfour. Notwithstanding the ostensible reason for his departure, Josiah Martin, once the Royal Governor of North Carolina, gives the game away in the postscript to his letter of July 24, where he remarks, “I beg leave to congratulate your Lordship on the loss of the late Commandant of Charles Town.” Promoted to major general on November 20, 1782, Paterson was to command British land forces in Nova Scotia after the war. Historians frequently misspell his surname.[3]

Alured Clarke

Lt. Colonel of the 7th Regiment (Royal Fusiliers), which was to be captured at the Battle of Cowpens, Clarke (c. 1745-1832) served on secondment from early summer 1780 as the military commander in Georgia and East Florida. It was a thankless task, especially in Georgia, for, bereft of troops except for those stationed at Savannah and Augusta, the province otherwise slipped soon out of his control. Yet he never complained, aware as he was of the paucity of men available to Cornwallis and the acute, insoluble problems that it presented. As to his character during the war, it is well assessed by a revolutionary opponent: “This excellent officer and perfect gentleman,” to whose name “no act of inhumanity or of oppression was ever attached, . . . gained the good will of the Americans by the gentleness of his government . . . and by the protection afforded to property when they [the British troops] finally retired on the evacuation of Savannah.” After the war he would be appointed Lt. Governor of Jamaica and then of Quebec, take part in reducing the Dutch colony at the Cape of Good Hope, and serve as Commander-in-Chief in India. He died a field marshal and Knight of the Bath at Llangollen vicarage, Denbighshire.[4]

John Harris Cruger

Born in 1738, Cruger belonged to an extended family which had been prominent in the public affairs of New York before the Revolution. He himself had been a member of HM Council for the Province, the Chamberlain of New York City, and, being well established in business, a member of the New York Chamber of Commerce. A son-in-law of Oliver De Lancey the elder, he was commissioned Lt. Colonel of the 1st Battalion, De Lancey’s Brigade, on September 6, 1776 and for the next two years was posted to Long Island. In November 1778 he came south with his men as part of the expedition which seized Savannah, and in autumn 1779 commanded one of the principal redoubts during the unsuccessful siege of the town by the French and revolutionaries. In 1780 he had remained there as part of the garrison, but on July 12, having been ordered to succeed Lt. Col. Nisbet Balfour in the Backcountry, he marched with his battalion for the village of Ninety Six, where he arrived by the beginning of August. There he would gain a deserved and abiding reputation for courage, activity, decisiveness, resolution, resourcefulness, vigilance, and exceptional leadership in the face of adversity—sterling qualities well displayed in The Cornwallis Papers and amply confirmed in 1781 during the Siege of Ninety Six and the Battle of Eutaw Springs. It was in fact no more than was expected of him, for on July 11, 1780, a day before his departure from Savannah, his measure had been rightly taken by Alured Clarke in a dispatch to Cornwallis, “If I may be allowed to judge from a very short acquaintance, I am convinced your Lordship will not be disappointed in your expectations from this gentleman, who will be greatly assisted by the zeal and good sense of Lt. Colonel Allen and the harmony that subsists between them.” At the close of the war his men settled in what became the Parish of Woodstock, New Brunswick, whereas he himself removed to London. Placed on the Provincial half-pay list, he sought compensation from the Royal Commission for his losses, having been subjected to confiscation by the revolutionary authorities. He died in London on June 3, 1807. Sadly, no portrait of him is known to exist.[5]

Isaac Allen

A son of an Associate Justice of the New Jersey Supreme Court, Allen was born in 1742, graduated from Princeton in 1762, and was admitted to the New Jersey Bar three years later. He practised in Trenton and was a warden of St Michael’s Church when the Revolutionary War began. On December 3, 1776 he was commissioned Lt. Colonel of the 6th Battalion, New Jersey Volunteers, and when it was incorporated into the 3rd, he was appointed Lt. Colonel of the expanded battalion on April 25, 1778. Like the 6th, the 3rd was posted to Staten Island, but in November 1778 it formed part of the expedition to Georgia. When the Franco-revolutionary assault on Savannah was repulsed eleven months later, the battalion occupied a position on the front left of the British line. In March 1780 the light company marched with Paterson to reinforce Clinton, while Allen and the rest of his men remained in garrison in Savannah. At the end of July he was ordered to march with them to reinforce Cruger, who, as previously mentioned, had gone ahead to command at Ninety Six. Like Cruger, Allen was an excellent officer commanding a well disciplined unit and would serve as an able second in the coming months, notably defeating Lt. Cols Elijah Clark and James McCall in the action near White Hall on December 12, 1780 and withstanding with Cruger the Siege of Ninety Six in the following May and June. At the close of the war he was placed on the Provincial half-pay list and settled with his men in what became the Parish of Kingsclear, New Brunswick, where he resumed the practice of law. Besides holding other offices, he went on to become a Judge of the Supreme Court, of which his grandson, Sir John Allen, later served as Chief Justice. He received partial compensation of £925 from the Crown for his property confiscated by the revolutionaries, which comprised a two-storey dwelling house in Trenton, a farm outside the town, and property in Philadelphia. He died at Kingsclear on October 12, 1806.[6]

George Turnbull

Turnbull (1734-1810) was a Scot. Having served twenty years as a lieutenant and then a captain in the 60th (Royal American) Regiment, he began to serve from 1776 on the British American establishment as a captain in the Loyal American Regiment. For his intrepidity, particularly in the capture of Fort Montgomery on October 6, 1777, he was promoted to the lt. colonelcy of the New York Volunteers with effect from the following day. Going south with his regiment in 1778, he took part in the capture of Savannah and then distinguished himself in breaking the siege of the town late in 1779. When, after the capitulation of Charlestown, Cornwallis arrived at Camden on June 1, 1780, he immediately assigned Turnbull to the command of the post at Rocky Mount, an eminence on the west bank of the Wateree several miles north of Camden. There, on July 30, he and his men ably withstood an assault on the post by Brig. Gen. Thomas Sumter. When Cornwallis embarked on the autumn campaign on September 7, a campaign intended to reduce North Carolina, Turnbull was left in command at Camden and remained so till shortly after Cornwallis’s withdrawal to Winnsborough, being superseded on November 13 by Col. Francis Lord Rawdon. Homesick, he was then given leave to return to New York, having advised Cornwallis in June, “There is surely a duty which a man owes his family, and if I see no relief after settling the peace and quiet of this province, I shall be drove to the disagreeable necessity to quit the service intirely [sic].” Like Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton, but unlike Cornwallis, Turnbull favored a policy of deterrence as the only means of pacifying conquered territory, an approach with which I agree,[7] but not to the extent advocated by him: “If some of them could be catched who have submitted and run off and join’d the rebels, an example on the spot of immediate death and confiscation of property might perhaps make them submit.” I also agree with him that mounting much of the infantry was an essential component of pacification:[8] “Dragoons or mounted men must be got to check those rebels which lays waste the country and murders the well affected in cold blood,” a view shared by Cruger: “Horse is the thing to cover this country.” Overall, Turnbull was an exceptionally brave, efficient officer commanding a well disciplined regiment, an officer who, in Cornwallis’s words, “tho’ . . . not a great genius, . . . is a plain rightheaded man.” When the New York Volunteers was disbanded at the close of the war, he was placed on the Provincial half-pay list. Married to a daughter of Cornelius Clopper of New York, he died in Bloomingdale, New Jersey.[9]

James Wemyss

Born in Edinburgh, Wemyss (1748-1833) had spent some ten years serving in the 40th Regiment and the Queen’s Rangers before entering the 63rd Regiment as major on August 10, 1778. An active, capable officer, he would command the regiment in South Carolina during 1780, in particular a detachment of his men and others on a controversial expedition to the Pee Dee during September, an expedition that gained him the undeserved but understandable sobriquet “the second most hated man in Carolina,” the first being Tarleton. How unwarranted the criticism of him was is set out in my description of the expedition appearing in this journal in 2016,[10] whereas the policy of burning homes, which he implemented on a vast scale, is justified in an essay of mine appearing elsewhere.[11] Wounded in the arm and leg in the action at Fish Dam Ford on November 9, 1780, he was captured and paroled later the same day. Lame, and with his health much impaired, he obtained leave by January 1781 to return to New York and took no further active part in the war. In August 1783 he was promoted to lt. colonel but sold his commission six years later and retired to Scotland. In the mid or late 1790s financial difficulties led him to migrate to America, where living was less expensive, and he purchased a farm in a quiet backwater of Long Island. He lived there till his death. Like the place in Scotland, his name was pronounced “Weems,” as evinced by Lt. Col. Moses Kirkland’s letter of October 31, 1780 to Cornwallis,[12] where it is spelt phonetically.[13]

Archibald McArthur

An accomplished, judicious officer of great experience and many years’ standing, McArthur had served with the Dutch Scots Brigade before entering the British Army and becoming a captain in the 54th Regiment. Promoted in 1777 to major in the 71st Highlanders, a corps raised two years earlier by Simon Fraser, sometime Master of Lovat, he accompanied his regiment to Georgia in 1778 and participated in its distinguished service there and in South Carolina during the next year. After the return to England of Archibald Campbell, Lt. Colonel of the 2nd Battalion, and with the departure to New York of Alexander MacDonald, Lt. Colonel of the 1st Battalion, command of the regiment devolved upon McArthur in mid June 1780. Almost immediately it was posted to the sickly village of Cheraw Hill on the eastern border of South Carolina, where well over a half, including McArthur, fell down at once with pestilential fevers. For this reason, but partly due to an approaching Continental force under Major Gen. Johann Kalb, the regiment was soon withdrawn, eventually to Camden, where the sick were hospitalised. By July 29 McArthur had still not recovered, so presumably did not command his fit men at the Battle of Camden. A worse and most undeserved fate was to befall him. On January 17, 1781 it was his misfortune to serve under Tarleton at the Battle of Cowpens, where, commanding the 1st Battalion, he and the remains of his men were captured. Paroled and exchanged, he would in April be promoted to Lt. Colonel of the 3rd Battalion of the 60th (Royal American) Regiment and continue to serve in South Carolina. Esteemed on both sides of the political divide, he was said by a revolutionary opponent to have had “no act of inhumanity or of oppression ever attached to his name.”[14]

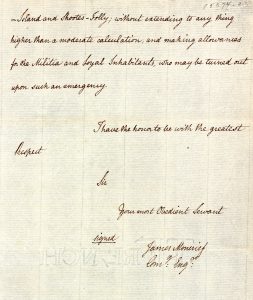

James Moncrief

Born in Fifeshire in 1744, Moncrief, as he signed his surname, had entered the Royal Military College, Woolwich in 1759, being commissioned an ensign in the Corps of Engineers three years later. Having been severely wounded during the siege of Havana in 1762, he was to serve for many years in the West Indies and North America. On the opening of the Revolutionary War he was present as a captain lieutenant at the capture of Long Island before taking an active part in the Battle of Brandywine and other operations of 1777 and 1778. It was, however, in the South where he gained his fame as an extraordinary military engineer, notably in 1779 in the defense of Savannah, in 1780 in the siege of Charlestown, and later in the formidable fortification of that place. For his services in Georgia he was promoted by brevet to major, and for those at the siege of Charlestown, to lt. colonel. It is perhaps no surprise that, assiduous as he was in his duties, and occupying the house of John Rutledge, the deposed revolutionary Governor, he came to incur the displeasure of the revolutionary party in South Carolina, being accused of malignity, oppression, and implacable resentment. And when Charlestown was evacuated in 1782, he is said to have carried off 800 slaves employed in his and the Ordnance departments and to have sold them in Jamaica for his personal profit. In 1793 he was mortally wounded in the siege of Dunkirk and buried at Ostend. Historians frequently misspell his surname.[15]

John Macleod

Having entered the Royal Regiment of Artillery as a cadet in 1767, Macleod (c. 1752-1833) was commissioned a 2nd lieutenant four years later and promoted to 1st lieutenant on March 15, 1779. Highly esteemed by Cornwallis, whose personal friendship he gained, he would command Cornwallis’s field train of artillery throughout the southern campaigns. “He is,” wrote Cornwallis to Balfour, “an excellent officer and a pleasant man to serve with in every respect.” Mentioned by Cornwallis in dispatches after the Battles of Camden and Guilford, he would be among the troops who capitulated at Yorktown. On returning to England, he was placed on the staff of the Master General of Artillery and was engaged till his death in the organisation of the regiment and in its arrangement and equipment for all expeditions, of which there were no fewer than eleven. Fulfilling the potential which Cornwallis had seen in him, he held successively the offices of Chief of the Ordnance Staff, Deputy Adjutant General, and Director General of Artillery, being promoted to major general in 1809 and to lt. general four years later. In 1809 he also commanded the artillery during the expedition to Walcheren. As a mark of his long and distinguished service he was made a knight in 1820, being invested with the Grand Cross of the Royal Guelphic Order. He died at Woolwich.[16]

James Simpson

Simpson was Secretary to the King’s Commissioners, namely Sir Henry Clinton and Marriot Arbuthnot, the British military and naval Commanders-in Chief, and would remain in this office during his service in the South. Highly esteemed as a percipient adviser on political, constitutional and legal affairs, he had by 1775 become Clerk of HM Council in South Carolina, a body which acted in two capacities, first as a privy council advising the royal governor in the exercise of his functions, and second as a legislative council forming the upper house of the legislature. In 1777, two years after the royal government was overthrown, he was banished from South Carolina for retaining his allegiance to the Crown. Two years later he went on commission to Savannah, then under British control, and from there reported to Clinton on the extent of loyalist sympathy in South Carolina, particularly in the Backcountry. On June 23, 1780, following the success of the Charlestown campaign, he was appointed Intendant General of Police for South Carolina, but his role would extend wider. He would continue to act as a valued political and legal adviser to Cornwallis and Balfour and be involved in adjusting much of the very complex business of Charlestown and the country. He was probably a Scot, for, aside from his official duties, he was soon to be elected President of the St. Andrew’s Society, a Charlestown Club established in 1729 of which most gentlemen in the Scottish community were members. Respected on both sides of the political divide, he would in February 1781 return to New York at the urgent behest of Clinton to resume his duties as Secretary to the King’s Commissioners. On his service in South Carolina a revolutionary opponent was many years later to comment, “It should forever redound to the honour of Mr. Simpson . . . that the only use which he ever made of his power and influence was to mitigate the sufferings of the unfortunate and by generous attention to free them from every taint of political animosity.” In December 1781 he would set sail with Cornwallis for England.[17]

John Cruden

A son of the Reverend William Cruden of London, John Cruden had been a merchant in Wilmington, North Carolina. In March 1775 he had at first refused to sign the association subversive of the royal government but had been “persuaded” to do so. Declining to take the test oath two years later, he was banished and saw his property confiscated. Repairing to the Bahamas by way of East Florida, he for a time resided in Nassau. On September 16, 1780 Cornwallis appointed him Commissioner of Sequestered Estates in South Carolina, an office designed to possess and manage, at least for the time being, the plantations of those who had gone off to the enemy or who, though residing peaceably at home, continued to avow rebellious principles—the justification being that the revenue derived from the plantations should be applied towards defraying the costs to Britain of a war that in British eyes the supporters of the Revolution had helped to foment. Zealous though he was in the execution of his office, and having seized initially almost 100 plantations and above 5,000 slaves, he soon saw his expectations dashed, for, soon after his appointment, the province and with it almost all the seized plantations were overrun by the enemy. Instead of anticipating an increasing annual revenue of £50-60,000,[18] he was involved in very heavy but unavoidable expense. On the evacuation of Charlestown in December 1782 he set sail for East Florida before moving on to Rawdon Harbor in the Bahamas by May 1785. Three years later, with his father dead and his mother, sister and her children dependent on him, he presented a claim to the Royal Commission in respect of his losses.[19]

Thomas Pattinson and John Carden

Pattinson (1738-1781) was an Englishman who had been promoted from the 17th Light Dragoons to the lt. colonelcy of the Prince of Wales’s American Regiment, a corps of loyalists raised on the British American establishment. On May 26, 1780, two weeks after the capitulation of Charlestown, they began to march from there for the village of Ninety Six, which was second in importance to Camden in the South Carolina Backcountry. Part of a medley of troops, they were under the overall command of Lt. Col. Nisbet Balfour, who had been seconded from the Royal Welch Fusiliers, a regiment now at Camden. By June 12 they had reached Hampton’s House on the south side of the Congaree, a few miles west of its confluence with the Wateree, from where Balfour penned to Cornwallis a few damning words about Pattinson: “He is so dead a weight that he cannot be trusted anywhere to himself, and his only use will be under someone at the principal post [Camden],” an assessment echoed later by Cornwallis and Rawdon. Consequently Pattinson with six companies of his corps was ordered to Camden on June 16. Soon afterwards Rawdon, who was left in charge there five days later on Cornwallis’s departure for Charlestown, had no option, due to the exigencies of the moment, but to entrust him with the command of the important post at Hanging Rock. What happened next is perhaps best left to Rawdon’s own words in his dispatch of July 31 to Cornwallis: “Finding my health pretty firm, and no immediate business pressing upon me, I made an excursion on the evening of the 29th to examine the state of our post at Hanging Rock. Upon my arrival there about eleven at night, I found Lt. Colonel Pattinson drunk. I therefore ordered him hither into close arrest.” Rather than face court martial, Pattinson resigned his commission and was placed on the Provincial half-pay list. He died in Charlestown sometime before its evacuation by the British.[20]

Commissioned as major in the Prince of Wales’s American Regiment in the summer of 1777, Carden assumed command of the troops at Hanging Rock on the arrest of Pattinson. They comprised not only the six companies of the corps ordered above to Camden but also the British Legion infantry and Col. Samuel Bryan’s North Carolina loyalist militia. Eight days later the post was vigorously attacked by Sumter and Major William Richardson Davie, who so roughly handled Carden’s own regiment that it afterwards ceased to be a materially effective force. According to some accounts Carden lost his nerve during the action and relinquished command to Captain John Rousselet of the Legion. He died at Charlestown on October 31, 1782. Historians frequently confuse Browne’s corps (as the Prince of Wales’s American Regiment was commonly called) with Lt. Col. Thomas Brown’s King’s Rangers, who played no part in the above affair.[21]

Henry Brodrick

The Hon. Henry Brodrick (1758-1785) was a younger son of George Brodrick, the 3rd Viscount Midleton. It has long been known that he was related to Cornwallis, but the precise relationship has to my knowledge never been ascertained. They were, in fact, second cousins, for Brodrick’s mother, Albania (née Townshend), was a first cousin of the 3rd Viscount Townshend’s daughter Elizabeth, who had married Cornwallis’s father. Commissioned an ensign on March 23, 1775 in the 33rd Regiment, of which Cornwallis was Colonel, Brodrick was promoted to lieutenant on August 8, 1776 and to captain in the 55th on June 12, 1777. During the Charlestown campaign he served in Cornwallis’s suite. Soon after, he sailed for England for the recovery of his health, but in mid January 1781 would rejoin Cornwallis in time to take part in the winter campaign as one of his aides-de-camp. On the conclusion of the campaign he was sent home with Cornwallis’s dispatches, setting sail from Charlestown on May 3 in HM Sloop Delight and arriving in England by mid June. On Cornwallis’s solicitation he was promoted to major and would in due course become a lt. colonel in the Coldstream Guards. Although not of age, he was MP for Midleton from 1776 to 1783. As in the Army Lists, his name is frequently misspelt by historians.[22]

[1]Ian Saberton, “The Revolutionary War in the South: Re-evaluations of certain British and British American Actors,” JAR, November 21, 2016.

[2]Ian Saberton ed., The Cornwallis Papers: The Campaigns of 1780 and 1781 in the Southern Theatre of the American Revolutionary War (“CP”), 6 vols (Uckfield: The Naval & Military Press Ltd, 2010).

[3]CP 1: 121 and 369; Benjamin Franklin Stevens, The Campaign in Virginia 1781: The Clinton-Cornwallis Controversy (London, 1887-8), 2: 449; WO 65/164(1) (UK National Archives, Kew).

[4]CP 1-3, 5 and 6, passim; Alexander Garden, Anecdotes of the Revolutionary War(Charleston, 1822), 264; Dictionary of National Biography (London, 1885-1901) (“DNB”).

[5]CP 1: 339, 2 and 3, passim; Lorenzo Sabine, Biographical Sketches of Loyalists of the American Revolution (Boston, 1864), 1: 343-6; Appletons’ Cyclopædia of American Biography (New York, 1888 et seq); John Austin Stevens, Colonial Records of the New York Chamber of Commerce, 1768-1784 (New York, 1867), 370; Todd Braisted, “The Memorial of John Harris Cruger of New York,” together with “A History of the 1st Battalion, De Lancey’s Brigade,” The On-Line Institute for Advanced Loyalist Studies, November 22, 2007; W. O. Raymond, “Provincial Regiments: De Lancey’s Brigade,” A Raymond Scrapbook (Fort Havoc CD 1); Treasury 64/23(9), WO 65/164(33), and WO 65/165(7) (UK National Archives).

[6]CP 1-3, passim; Hamilton Schuyler, A History of Trenton 1679-1929 (Princeton University Press, 1929), ch. II; Braisted, “A History of the 3rd Battalion, New Jersey Volunteers,” The On-Line Institute for Advanced Loyalist Studies, November 23, 2007; Raymond, “Provincial Regiments: The New Jersey Volunteers,” A Raymond Scrapbook; Benson J. Lossing, The Pictorial Field-Book of the Revolution (New York, 1855), 2: 530; Treasury 64/23(7), WO 65/164(35), and WO 65/165(6) (UK National Archives).

[7]Ian Saberton, “Was the American Revolutionary War in the south winnable by the British?” in his The American Revolutionary War in the south: A Re-evaluation from a British perspective in the light of The Cornwallis Papers (Grosvenor House Publishing Ltd, 2018), 4-5, 15-16.

[9]CP 1-3, passim; Army Lists; Treasury 64/23(2), WO 65/164(31), and WO 65/165(2) (UK National Archives); Sabine, Biographical Sketches, 2: 367; Stevens, The Campaign in Virginia 1781, 2:460.

[10]See Ian Saberton, “The Revolutionary War in the South: Re-evaluations of certain Revolutionary Actors and Events,” JAR, 6 December 2016.

[13]CP 1-3, passim; Army Lists; Margaret Baskin, “James Wemyss (1748-1833),” Banastre Tarleton and the British Legion: Friends, Comrades and Enemies (www.banastretarleton.org, June 29, 2005).

[14]CP 1-3, passim; Roderick MacKenzie, Strictures on Lt. Col. Tarleton’s History of the Campaigns of 1780 and 1781 in the Southern Provinces of North America (London, 1787), 108-9, 111; The Hon. George Hanger, An Address to the Army in reply to Strictures of Roderick M’Kenzie (late Lieutenant in the 71st Regiment) on Tarleton’s History of the Campaigns of 1780 and 1781(London, 1789), 99, 107; Mark Mayo Boatner III, Encyclopedia of the American Revolution (D. McKay Co., 1966); DNB; Garden, Anecdotes (1st series), 264; idem, Anecdotes of the American Revolution, Second Series (Charleston, 1828), 103.

[15]CP 1-3, passim; DNB; Boatner, Encyclopedia, 712-3; Appletons’; Garden, Anecdotes (1st series), 234, 268-9; William Johnson, Sketches of the Life and Correspondence of Nathanael Greene (Charleston, 1822), 2: 369.

[16]CP 1-6, passim; Army Lists; Anon., List of Officers of the Royal Regiment of Artillery from the Year 1716 to the Year 1899 (London, 1900), 13, 167-8, 199, 232.

[17]CP 1-3 and 6, passim; John Drayton, Memoirs of the American Revolution from its Commencement to the Year 1776 (Charleston, 1821), 1: 160 and 2: 4; George Smith McCowen Jr., The British Occupation of Charleston, 1780-82 (University of South Carolina Press, 1972), 16, 17, 44, 124; Robert Stansbury Lambert, South Carolina Loyalists in the American Revolution (University of South Carolina Press, 1983), 27; Garden, Anecdotes (2nd Series), 104.

[18]Approximately £9,000,000 ($11,300,000) to £10,850,000 ($13,560,000) in today’s money.

[19]CP 1-3 and particularly 6, passim; Robert O. Demond, The Loyalists in North Carolina during the Revolution (Duke University Press, 1940), 54, 66, 184; Lambert, South Carolina Loyalists, 236, 264; Peter Wilson Coldham, American Loyalist Claims (National Genealogical Society, 1980), 111.

[20]CP 1: 84, 90, 109, 215, 222-3, 226-7; Treasury 64/23(35) and WO 65/165(16) (UK National Archives); Sabine, Biographical Sketches, 2: 153).

[21]CP 1: 183, 208, 223-4, 2: 343-4; Banastre Tarleton, A History of the Campaigns of 1780 and 1781 in the Southern Provinces of North America (London, 1787), 92; Anne King Gregorie, Thomas Sumter (R. L. Bryan Co., 1931), 93; Robert D. Bass, Gamecock: The Life and Campaigns of General Thomas Sumter (Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1961), 70; Sabine, Biographical Sketches, 1: 294; Royal Gazette (New York), December 4, 1782.

[22]CP passim, particularly 4: 117; Alan Valentine, The British Establishment, 1760-1784: An Eighteenth-Century Biographical Dictionary (University of Oklahoma Press, 1970); Franklin and Mary Wickwire, Cornwallis: The American Adventure (Houghton Mifflin Co., 1970), 15; Stevens, The Campaign in Virginia 1781, 2: 408; Army Lists.

2 Comments

Since I live near Charleston, SC and am a member of the DAR, I found this article most interesting. Thank you for your research.

Delighted, Cynthia, that it was of interest.