When dealing with available sources to investigate questions related to historical events, the researcher has at his disposal a limited set from which to choose. Contemporaneous accounts, reports, maps, plats, legal filings, and location evidence exist in a more or less complete record. Nevertheless, linking the elements bearing witness to one event or another is limited by the fact that quantitative analysis, across multiple data sets, is a modern invention. Navigation based on known, regularized coordinates only became available in the middle 1700s. Instrumentation to measure location and distance is also of modern origin.

Creating maps with accurate local detail has made plats or land resurveys great resources, but very difficult to “sew” together since they generally contain very few identifiable topographic features and are at various scales. The advent of geographical information systems (GIS) has caused major improvements in quantitative mapping. The ability to relate maps done on known scales has made for a whole host of applications when coupled with modern remote sensing from sources such as aircraft cameras, spacecraft imagery, surveyed maps, GPS mapping and laser scanning LIDAR. These applications include county property mapping, road routing, commercial company siting, business locating, and the like. Using GIS to corroborate the historical record compared to quantitative maps is an obvious potential application.

The Battle of Eutaw Springs has associated with it an historical mystery concerning the details of the distribution of troops and their actions. What follows is an illustration of applying GIS to the historical record. The result is a proposed resolution of that mystery that allows the historical narrative to be reconciled with a correct geographical interpretation. A venerated map passed down in time from 1822 until today will need to be redone.

Background

(The following description is adapted from Henry Lee, 1812.) Early on the morning of September 8, 1781 groups of British soldiers camped near Eutaw Springs were awakened in preparation for a morning chore. These soldiers had been detailed to foraging and were drawn from the major units under Lt. Col. Alexander Stewart’s command. These men represented the last large-scale Royal Army command left in the Carolinas. Lord Cornwallis, after having been staggered at Guilford Court House, had refitted at Wilmington and moved his army north and, a month later, would meet his undoing at Yorktownin Virginia.

The foragers moved up the Congaree River Road turning down one or another of the various paths that led down to the Santee River plantations. Waiting for the commissary wagons coming from Charlestown was a matter of irritation, since the deliveries were fraught with peril and delay. Partisan rangers were likely to swoop down and capture food and escort. Adequate provisions were always in short supply.

September is the month for harvesting sweet potatoes in South Carolina and this little army of a couple thousand regulars and American tory volunteers intended to supplement their meager provisions while waiting for the promised wagons coming from Charlestown. No intelligence of Rebel forces had been gained from the various patrols and scouts sent out by Lt. Colonel Stewart. Ominously others had failed to report back. Nevertheless, Lt. Colonel Stewart had taken the precaution of sending an escort of cavalry under Major John Coffin to shepherd the little band, just in case.

As the foragers had gotten about four miles from the British army camp, a group of unidentified horsemen appeared in the road. Immediately Major Coffin charged and just as quickly his troopers were shattered: He had run straight into the vanguard of three thousand troops of the massed patriot army in South Carolina.

Gen. Nathanael Greene had marched his army from Burdell’s plantation, seven miles from the British camp down the Congaree River Road, to attack Stewart. Now aware of their danger, the foragers reacted with confusion and panic. Some had been armed and fought back. Others, troops Stewart would soon sorely need, hid in the forest only returning after the battle.

Panicked horsemen, remnants of Coffin’s command, came rushing back into Stewart’s camp raising the alarm. It was full morning now and the British Army, although caught unaware, quickly formed for battle. Lieutenant Colonel Stewart formed one line stretching from the creek formed by the Eutaw Springs that leads to the Santee River, then athwart the Congaree River Road and continuing into the open woods to the south. He placed a pair of his three pounder cannon in each of two batteries along his line as the Americans approached. He waited.

Thus began one of the most obstinate, bloody and chapter ending battles of the Revolution. In the aftermath, never again would a British Army venture into the interior of the Carolinas or Georgia. The disasters of the year before such as the fall of Charlestown and Gate’s defeat at Camden, had somewhat been set right. The much-maligned southern militia had grown into now-seasoned troops who fought volley-to-volley and bayonet-to-bayonet against trained British troops. The day after the battle, the British Army scurried to Charlestown, in near panic, leaving behind their most seriously wounded, their abandoned weapons and their reputation. Patriots now controlled the liberated colony except for a small enclave around Charlestown.

The importance of this battle fought a month before Cornwallis’s surrender at Yorktown has been very much overshadowed by the great events in Virginia. Lately, however, more attention has been shown to this great battle along the Santee, engendering a re-examination of the events of September 8, 1781.

A Map Appears and a Mystery Develops

Beginning shortly after the Revolution, histories began to be written that offered records, critiques, and points of view related to the war. One of the earliest publications came from Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton in 1787, A History of the Campaigns of 1780 and 1781, in the Southern Provinces of North America. Tarleton was not in the battle himself but was engaged in a running dispute with some fellow officers primarily over who was at fault in his disaster at the Cowpens. Nevertheless, he included in his history correspondence from Lieutenant Colonel Stewart to General Cornwallis.

In 1812 Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee published his Memoirs of the War in the Southern Department of the United States which contains a detailed account of the Battle of Eutaw Springs. He was a participant as colonel of the Virginia Legion.

In 1822 Dr. William Johnson published Sketches of the Life and Correspondence of Nathanael Greene, Major General of the Armies of the United States in the Revolution In Two Volumes. Johnson was a physician who lived from 1771 to 1834, served in the House of Representatives, and was an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court. Johnson and his brother Dr. Joseph Johnson actually slept in the so-much-fought-over Eutaw Springs brick house the year after the battle when they were youngsters.

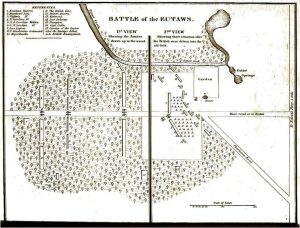

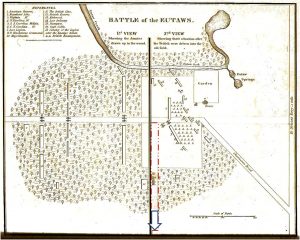

Dr. Johnson’s 1822 book has in it the first map of the Battle of Eutaw Springs, presented in two-stage panels. There is no attribution to this map, but careful inspection of the map border shows the inscription, “H.S. Tanner, Sc” which indicates Sculptor or the engraver of the map. H.S. Tanner was a well-known publishing house in Philadelphia and was used by the Supreme Court for publications. The map was likely commissioned for the book by Dr. Johnson who was a member of the Supreme Court at the time and would have most certainly been familiar with H.S. Tanner.

Shown in Figure 2 is the two stage map from Dr. Johnson’s book. While the sources that led to the creation of the map are unknown, it is well discussed in the book:

At about two hundred yards west of the Eutaw Springs, Stewart had drawn up his troops in one line, extending from the Eutaw Creek beyond the main Congaree road. The Eutaw Creek effectually covered his right, and his left, which was in the military language, in air, was supported by Coffin’s cavalry, and a respectable detachment of infantry, held in reserve at a convenient distance in the rear of the left, under cover of the wood. . . . The American approach was from the west; and at a short distance from the house, in that direction, the road forks, the right-hand leading to Charleston, by the way of Monk’s Corner, the left running along the front of the house by the plantation of Mr. Patrick Roche, and therefore called, by the British officers, Roche’s road; being that which leads down the river, and through the parishes of St. Johns and St. Stephens. . . . The artillery of the enemy was also posted in the main road. . . . [Author’s emphasis]

The Map is Easily Shown to be Severely Flawed

The descriptions and the associated map are easily demonstrated to be incorrect. What follows outlines the questions surrounding the map. Objections can be raised concerning at least four major areas.

The first objection relates to the map depiction of the distribution of the artillery and military units. Referring to the two primary eye-witness sources, Stewart and Lee, we have from the report of Stewart in his September 19 letter to Cornwallis:

I immediately formed the line of battle with the right of the army to the Eutaw branch and its left crossing the road leading to Roche’s Plantation, leaving a corps on a commanding situation to cover the Charleston road and to act occasionally as a reserve.

And again from Stewart in the same report:

the action was renewed with great spirit; but I was sorry to find that a three pounder, posted on the road leading to Roche’s, had been disabled, and could not be brought off when the left of the line retired.

While Lee wrote:

The artillery was distributed along the line, a part on the Charleston road and another part on a road leading to Roache’s plantation, which passed through the enemy’s left wing.

Both officers, Lieutenant Colonel Stewart, who directed the deployment of the single British line, and Lieutenant Colonel Lee, commanding the right of the American advance, refer to the existence of two batteries of artillery, one of which was along a road to Roche’s, or Roache’s. Moreover, both men refer to the deployment of the British line as extending from the springs on the north in a southerly direction with the left posted on or crossing the road to Roche’s.

The Johnson map cannot possibly be an accurate rendition of the battlefield as described by these independent observers, since it does not show either the British troops extending from the springs, posted on or crossing both the Congaree River road, and a “Road to Roche’s.”

The second battery of artillery which was posted on the described road is missing from Dr. Johnson’s map. It was, in fact, one gun from this battery which remained in the possession of the American Army after it had lost the other pieces of artillery in the attack on the brick house British headquarters during the battle.

The second objection is that Dr. Johnson’s map with a road to Roche’s as shown would represent illogical posting of a battery of artillery to the east of the battle and firing through his own men and camp. This piece was lost to the west of the springs and house. In no description of the battle is it stated that Americans went around the British, gaining their rear to offer such a target from that location.

A third objection concerns the River Road depicted on the map. Was there actually a “River road” during the time of the battle? The roads in the area of the battlefield were at various times “established” by the South Carolina Assembly and as such became public roads. The development of these roads can be followed through the Acts of the General Assembly Related to Roads, Ferries (hereafter, “the Acts.”)

The Congaree River road, (oddly, also known as the Road to the Congarees when headed inland and the Monck’s Corner Road, or the road to Charlestown when headed to the coast), certainly existed as a public road established by the General Assembly but it was not until the early 1800s that the General Assembly authorized a road along the Santee from St. Stephens and then later to the Eutaw Springs itself. This can be seen from early maps of the period as well as state establishment of public roads as found in entries in the Acts.

In 1786, after the battle and much before the publication of Dr. Johnson’s book, the General Assembly authorized the completion of a “River Road”:

Be it enacted, by the Honorable the Senate and House of Representatives, now meet and sitting in General Assembly, and by the authority of the same, that a public road shall be laid out in Saint John’s Parish, Marion County, from the Saint Stephen’s road, along Santee River, to the Congaree road near the Eutaws.

A fourth objection arises from a search of recorded plats.While the Roche family is well represented in the history of property owners in the low country until the early 1800s, a search of the registered plats from the colonial period do not show any evidence that the road to the east went by any property owned by Patrick Roache or Roche.

We are led to the conclusion that the “Road to Roche’s” is misidentified on the Johnson Map. Nevertheless, a road must have existed since all the eyewitness accounts are in agreement in this regard. But if the road to Roacheswas not as shown on the map, a rational alternative supported by evidence needs to be found.

Search for the “Road to Roches”

What has been established from the narratives is that a road existed in 1781 and that it was positioned to accommodate the British left-wing and simultaneously host two pieces of artillery. Because the British had to generally face perpendicular to the Americans coming from a westerly direction, and the road passed through the left of the British line, the road must have extended in a somewhat southerly direction. Furthermore, the road had to be at least two hundred yards or “a few hundred paces” from the British camp. Given the objections to the Johnson map, the battle narratives show that there was a road to Roche’s. Where was it, if it was not the one referred to by Johnson?

Finding such a road could be simple enough if it had come into common use and been established as a public road, but searches for a public or much-used road have proved fruitless. Maps from the period are generally large scale and rarely capture roads of secondary, let alone tertiary, importance. County maps are nonexistent until much later. Plats do capture small road or paths, but are rarely easy to locate on a large scale map due to the lack of geophysical features. One hope in finding the mystery road lay in the possibility that the road retained some use until modern times when more advanced mapping techniques came into use.

A major stumbling block to the search for the mystery road lay in the damming of the Santee River to form Lakes Marion and Moultrie, done by the Corps of Engineers in the late 1930s to early 1940s. Accurate maps created after that time are readily available, but have on them the effects of Lake Marion flooding of Eutaw Creek. Nevertheless, many of the Santee River plantations, drowned roads and relocated roads still carry with them original names. Thus, accurate maps with which to begin a road search are limited to those created before the 1930s.

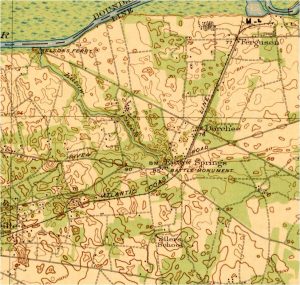

A good source for well-referenced map information comes from the United States Army which produced maps that showed roads, topography, schools, towns, and land marks (cartographic information). These maps were first generated from field surveys and printed on paper. Some maps exist for the Eutaw Springs area as early as 1921 and have been archived by the University of South Carolina Digital Collections, Topographical Maps of South Carolina 1888-1975 (www.sc.edu/library/digital/collections/topomaps.html), among others. One map, Eutawville Quadrangle, is fifteen minutes of longitude by fifteen minutes of latitude and has been used as a high resolution base map that can bridge historical maps with modern, surveyed maps.

Examining the area around Eutaw Springs can be done by zooming in to the specific area of the battle as has been done in Figure 3.

The “modern” River Road (with slight modifications from the 1786 General Assembly authorization) can be found passing through the area of the battle and forking to the north-east on the right side of the Battle Monument. The Monck’s Corner road can be seen passing to the south-east from the Battle Monument. Note that the River Road in this 1921 map was numbered as State Route 45 before Lake Marion was formed. Some of the road disappeared under the newly formed lake.

A number of dotted roads, indicating unimproved or dirt roads, are on the map as well as paved or otherwise improved roads. To the west of the Battlefield Monument, only one appears to travel in a southerly direction. The distance from the battlefield fits the descriptions from Lee and others of a couple hundred or so paces (one pace is approximately two and a half feet), or about five hundred feet from the monument.

The suggested “Road to Roches” has been called “Brigade” (modern historical, South Carolina Department of Natural Resources Orangeburg County GIS Roads, “rds75”) or, as of 2019, “Yahoo Road” plus “Oilers Road” and a section of “Cartoon Circle” (for a modern detail of the segments in this area see, Orange County South Carolina GIS gis2.orangeburgcounty.org/maps/.) This road represented a possibility that met many subjective criteria but without corroborating support. An onsite inspection shows that there are currently driveways and one or two subdivision entrances along Route 6 as it changes course and heads to Monck’s Corner from the monument.

The connection to the Roches: Evidence of the Plats

Plats contain information to provide testing for the suspected Roches Road location. The role of the plats now takes center stage.

Guided by the reasoning that the Johnson map was in error and that the comments by Lieutenant Colonel Stewart and Lieutenant Colonel Lee of their observations as to which direction the “Road to Roche’s” must have gone, a search for possible plantations associated with the Roche family was begun. The evidence of residual roads heading south from the battlefield also suggested the possibility.

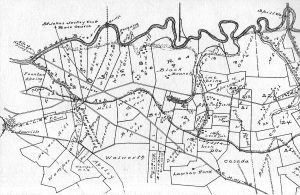

A “Map of Santee Cooper Project” (May 1951 version of an older map) depicts plantations expected to be flooded by the Santee Cooper Project. Many times old plantations acquired a name that was passed down year-to-year and became property tracts. Referring to this map, it can be seen that there were plantations to the south of the battlefield in the direction of Sandy Creek. The origins and title history of the plantations were investigated to find likely matches.

Examination of one of the tracts of land on the Corps of Engineers map of land to be flooded, a 700-acre tract named Wampee, led to the name Francis Roche. The Roche family appears early and prominently in the colony, beginning with Patrick Roche’s property in St. Thomas and St. Denis Parish around 1710. By the 1770s-1780s the family included four brothers, Ebenezer, Francis, Thomas, and Patrick, and two sisters, Elizabeth Motte and Mary Miller. After the early 1800s the male line no longer appears in property records.

Four thousand acres granted to William Thomson in 1786

A 4,000-acre tract was surveyed and granted in 1786 to Col. William Thomson. The tract is in Charleston District “on a Creek called Sandy Run, Waters of four holes.” The 1786 plat shows Thomson’s 4,000-acre tract: Bounding northwestward on the “District Line” between Charleston and Orangeburgh districts and bounding northeastward on “Francis Roach’s Land.” The plat implies that “Francis Roach’s Land” adjoins most of the Thomson tract’s northeastern property line.

This District Line was defined at various times by the Assembly, while the surveyors depicted it on various plats consistently as “The District Line terminates at Nelson’s ferry, and with the bearing Northeast at an angle of 54 degrees” (although there were indicated some minor adjustments as to the exact bearing). (See, for example, 1786 August 20 SCDAH, State Plats, Charleston Series S213190, Vol. 20, page 132 and 1786 December 4 SCDAH, State Land Grants, Series S213022, Vol. 16, page 342.)

Thomson tract partially resurveyed in 1829

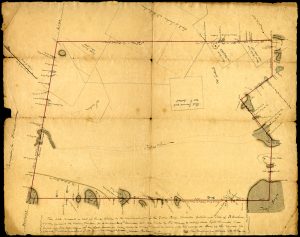

The South Carolina Historical Society houses a May 1829 plat with the somewhat misleading title “Plat of Eutaw Springs” and misleading summary “Plat (resurvey) of the Eutaw Springs Plantation.” Actually, the plat is an 1829 resurvey of the above-described 4,000-acre tract granted in 1786 to William Thomson and completed in 1830:

This plat represents a tract of Land situate in the Neighbourhood of the Eutaw Springs, Charleston District and State of So Carolina, originally granted to Col William Thompson [sic] for 4000 Acres on 4th December 1786. But found by this resurvey to contain about Eight thousand, four hundred and fifty / 8450 / Acres. I say about, because not having closed the survey I cannot be certain of the true content. Done at the request of William Thompson [sic] and James Smith Esquires in May 1829 —— Charles Parker

Inside the northeastern corner of William Thomson’s 8,450-acre tract, the 1829 resurvey plat delineates part of “Frances [sic] Roche’s grant dated 4th Decr 1786.” Also inside the northeastern corner, the resurvey plat delineates part of “Farr Grant now Capt Gaillard,” including “Capt Gaillard’s House.” The tract was resurveyed in 1829 at the request of William Thompson (actually William Sabb Thomson, a grandson of Col. William Thomson) the original grantee in 1786. The 1829 plat is South Carolina Historical Society Call No. 32-55-06.

A more detailed version of this plat was completed in 1832 (Charleston District, Court of Common Pleas, Judgment Roll, 1832 #109A (L 10018 Box 315), South Carolina Department of Archives and History). While the 1832 plat is well worth examining for the artistically excellent rendering, it does not add any additional identifiable geographical landmarks.

Georeferencing

One of the capabilities typically included in Geographical Information Systems is the ability to convert a properly-organized depiction of mapped objects without a geographical basis into one that has a geographical basis. This process is called georeferencing. The map to be processed must have objects plotted in proper relationship to one-another and with identifiable geographical features. For mapping, the identifiable features might be crossroads, rivers, topography, etc., features that can be given known locations in some coordinate system.

The unknown depiction can be georeferenced to another map that is properly surveyed in a coordinate system or by assigning coordinates to the un-georeferenced map. The conversion is done mathematically to assign coordinates to the map, making it viewable and useable as a quantitative object. This identification is done by matching objects to the same objects on the reference map. The mathematical operations can be simple rotation and scaling or much more complex algorithms. The quality of the georeferencing is determined from reports on residual errors incurred during the mathematical processing. In this fashion poor conversions can be rejected. The new map can be used along with other map-like data sources for a virtually limitless set of quantitative cross assessments and analyses.

How the georeferencing was informed by the plats: Evidence from the GIS

Once the identification of a property belonging, at one time or another, to a person named Francis Roche was made in the grand plat the question was, what is the hope that it can be geo-referenced? Typically this is not possible for small plats since they include no features relatable to some more or less immutable feature like a creek, river, road, canal, etc., which lasted long enough to be surveyed in some quantitative coordinate system.

One feature that does stand out on the plat is Toney Bay. Bays appear to be sinks, low areas of terrain that suggest a shallow pond holding water after suitable periods of rain. If the bay is impressive enough, it may be identified with a name. Such is the case of Toney Bay, which is still found on maps.

The plats have dimensions and angles on them, so in principle it is possible, if not easy, to orient the plat and then stretch it or compress it until the sides match the scale of the map on which it is being georeferenced. For this “Rosetta Stone” plat, however, there is the additional clue as to its location. One edge of the grand plat is identifiable as the “District Boundary,” discussed earlier between the relatively newly created County of Berkeley and Orangeburg County. Aligning of the plat then becomes a simpler geo-referencing problem amenable to GIS software.

This “Rosetta Stone” plat was imported into an open-source GIS system called Quantum Geographical Information System (Qgis), and georeferenced on the 1921 Eutawville Quadrangle introduced earlier as Figure 3 (which itself had been georeferenced onto a map canvas using the NAD 27 UTM Zone 17N projection). Modern road and hydrological features were also georeferenced. The very surprising result is shown in Figure 7.

Synthesis of the GIS and Plats

After the plat was georeferenced, it was clear that the area identified with Francis Roche was apparently connected to the Congaree road by the suggested road identified earlier. On the GIS “canvas,” a line was traced along the suspected road until it reached the area of the Francis Roche property as shown on Figure 8.

With this identification made, further support was found in a letter from Francis Marion to General Greene on September 21, 1781, that the British had reoccupied some of the abandoned ground around Eutaw Springs, twelve days after the battle:

Majr Doyle Commands the main body at Mrs Fludds (within three miles of Eutaw) they are Collecting Negroes to Intrench, but give out they Intend to pass the river. Their Army is much Sctterd, a part is at Majr Olivers at Eutaw, & Mr Roches, Either of them is three miles from the main body at Mrs Fludds.

An examination of the area around the likely road on the GIS map shows that the distance from the battlefield area is 2.4 miles.

To show how the Battle of Eutaw Springs could be better illustrated, Figure 9 shows a notional modification of Dr. Johnson’s 1922 map to reflect the modern interpretation of the facts. In this map, the Road to Roches is shown headed approximately due south. Along this road Lieutenant Colonel Stewart placed two of his three pounders, one of which he lost during the battle. The River Road or “to Roches” is now removed in agreement with the historical record of established roads of South Carolina in this area.

Discussion and Conclusion

The use of topographic and hydrological features makes it possible to extend the process of describing history correctly in geographical terms even before the existence of maps with widely known coordinates. The application of GIS to historical studies is particularly useful when geographical questions arise concerning the historical record. After the mid-1700s well-known coordinate systems began to be incorporated into maps that make it possible to relate features, and events to modern locations.

The example presented here has demonstrated the power of reviewing history subject to the physical strictures of a quantitative representation of the local environment. The map produced by William Johnson in 1822 has been shown to be unrepresentative of the events of this famous battle. This map used, copied and reused in histories as far as modern times has been shown to be fanciful in some respects.

Applying Geographic Information Systems techniques coupled with archived plats has been shown to offer a solution to an historical mystery. The search for the missing road has been shown to have benefitted greatly from a lucky find in the plats: a geographically referenced feature, the District Line. This is, however, rarely the case.

While it cannot be more than proposed from the evidence presented here that this road is in fact the one on which Lieutenant Colonel Stewart placed two of his cannon, the independent paths by which the proposed correct “Road to Roches” was identified makes it a strong alternative to the clearly inadequate depiction and description found in William Johnson’s Sketches. Nevertheless, a clear case has been made for revising the historical record. More corroborating information may yet be found to support or possibly refute what has been found. Going forward, historians should consider the alternative view of the battlefield as proposed here in addition to the only other one that has been available.

ACKNOWLEGDEMENTS

Richard Watkins of Saint Matthews, South Carolina, provided the foundation on which this work is grounded. Dick has rigorously researched the Roche family in the South Carolina Department of Archives and History, the South Carolina Historical Society archives, and various others. Tracking down the Roche family led to plats (the one referred to as “the Rosetta Stone Plat”) containing Wampee Plantation and with it, the road from the battlefield to Roche’s. Without Dick’s contribution, this work could never have been successful.

REFERENCES

- William Johnson, Sketches of the Life and Correspondence of Nathanael Greene, Major General of the Armies of the United States in the Revolution In Two Volumes,Printed by A.E. Miller, Charleston, SC, 1822.

- Joseph Johnson, Traditionsand Reminiscences, Chiefly of the American Revolutionin the South: Including Biographical Sketches, Incidents, and Anecdotes,Few of which Have Been Published, Particularly of Residents in the Upper Country, Walker and James, Charleston, SC, 1851.

- Banastre Tarleton, A History of the Campaigns of 1780 and 1781 in the Southern Provinces of North America, Dublin, 1787.

- Henry Lee, Memoirs of the War in the Southern Department in the United States, In Two Volumes, Bradford and Inskeep, Philadelphia, 1812.

- Henry Lee, The American Revolution in the South, Edited by Robert E. Lee, University Publishing Company, New York, 1869.

- The life of Nathanael Greene, major-general in the army of the Revolution, edited by W. Gilmore Simms, George F. Cooledge & Bro., New York, c1849.

- The Statutes at Large of South Carolina; Edited Under the Authority of the Legislature by David J. McCord. Volume the Ninth, Containing the Acts Relating to roads, Bridges and Ferries, with an Appendix Containing the Militia Acts Prior to 1794, A.S. Johnston, Columbia, SC, 1841.

- Last Will & Testament of Ebenezer Roche, Probated June 4, 1784. From Abstracts of Wills of Charleston District 1783-1800, compiled and edited by Caroline T. Moore.

- University of South Carolina Digital Collections, Topographical Maps of South Carolina 1888-1975 (sc.edu/library/digital/collections/topomaps.html), Eutawville Quadrangle.

- 1829 plat from South Carolina Historical Society, Call No. 32-55-06

- 1832 finished plat from Charleston Deeds, Volume Z-4, page 260Charleston District, Court of Common Pleas, Judgment Roll, 1832 #109A (L 10018 Box 315), South Carolina Department of Archives and History.

- The Papers of General Nathanael Greene, Volume IX 11 July 1781-2 December 1781, Dennis M. Conrad, Editor, The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill and London, Published for the Rhode Island Historical Society, 1997.

5 Comments

After the Santee River was dammed and Lake Moultrie/Marion were formed, did you find that that the actual location of the brick house was kept from the public in order to keep souvenir hunters at bay? I understand that a lot of the land now is on private property which keeps looters out. Thanks for the great article and the discovery of the southern Roche road.

The brick house foundation is in the existing battlefield monument area. Apparently it fell in a few years after the battle. The area is weak limestone with springs that have come and gone. Battering from the six pounders did nothing for the house structural stability. Nevertheless, a year later the house was still there when William Johnson came with is family from Charlotte on their way back to Charleston. Johnson was twelve at the time. What stories the young lad with wide eyes must have heard staying in that house! I do not know who the owner of the house was, but it is likely it was the heirs of Mary McKelvey as one of the area plats indicates.

I was at Eutaw Springs yesterday, using Dunkerly and Boland to trace events and places. Great to have this appear immediately after while the geography is fresh in mind. Will study it carefully. Thanks for this work.

Thanks for a great article. My sister-in-law has a lake cottage on Ash Hill Dr near Nelson Ferry Rd and a mile east of the Monument. I now see the origins of this name and its location going back to the 1921 map. My wife and I are fortunate that Thomas Heyslet and George Clifton (Va/Del Continentals) survived this bloody affair.

Many thanks for all your thorough and excellent work on this project regarding the Battle of Eutaw Springs. How can I get some help locating “Burdell’s Plantation” (para. 8 of your article)? John Burdell is my fourth great grandfather. Another source (perhaps you also) recounted that Generals Francis Marion and Nathaniel Greene had encamped their troops at Burdell’s Tavern and plantation September 7, 1781 before the Battle September 8th. Billy Burdell July 23, 2024 ws****@co*****.net