One would expect that a country that had been at war for five years would welcome its first ally with open arms. We might have mental images of civic officials leading throngs of eager citizens to greet the allies or of platoons of soldiers firing salutes. It didn’t happen. No government officials, no military officers or soldiers, nobody was at the pier to greet the French troops when they arrived at Newport, Rhode Island.

The Comte de Rochambeau arrived at 3 PM on Tuesday, July 11, 1780. He ordered the Amazone to be the only ship to dock at Long Wharf. Armand Charles Augustin de la Croix, Duc de Castries noted in his journal: “When he disembarked he [Rochambeau] found no one to receive him. He had to find lodging at the inn and it was only the next day that he could meet the governor of the city (General William Heath).”[1]

General Rochambeau and Mr. Jacques de Béville, quartermaster general of the army, were the only men to disembark on July 11. The rest of the fleet, with about 5,800 troops and 6,000 sailors and marines, anchored in the harbor in very heavy fog after a passage of seventy-one days and three and half months on board ship.

General Rochambeau’s second in command, the Baron de Vioménil (Antoine Charles du Houx baron de Vioménil) did not think it prudent to leave General Rochambeau alone on land, so he ordered the grenadier company of the Bourbonnais Regiment to disembark to be his guard.[2]

General Rochambeau and Mr. de Béville reconnoitered the area to select a campsite. Count Jean-François-Louis de Clermont-Crèvecoeur noted that General Rochambeau “was astonished to find hardly a soul. The shops were closed, and the local people, little disposed in our favor, would have preferred at that moment, I think, to see their enemies arrive rather than their allies. We inspired the greatest terror in them. The general had all the difficulty in the world finding lodgings.”[3]

The only person they encountered was a Quaker named Mr. Wanton (probably John Wanton). Wanton approached General Rochambeau and loaned him some horses and offered him some tea at his house which Rochambeau accepted. Rochambeau asked if the Americans had a commander in town. Col. Christopher Greene of the Rhode Island Regiment, a relative of the current governor and cousin of Gen. Nathanael Greene, was at Newport with a dozen men. General Rochambeau immediately sent an express to inform him of the arrival of the French.

General Rochambeau expressed his disappointment at not having anybody greet him upon his arrival, so an illumination was ordered for the following day, July 12. “The Whigs put 13 Lights in the Windows, the Tories or doubtfuls 4 or 6. The Quakers did not chuse their Lights shd shine before men, & their Windows were broken.”[4]

General Rochambeau decided to set up the camp on the south side of the city, facing the ocean where the British were expected to land if they wanted to attack Newport. The French troops landed at Wood’s Castle, now known as Sachuest Point, five miles from the camp. It took four days to land them all. A guard of a lieutenant and three squads (about ninety men) was posted at the landing site daily throughout the French occupation.

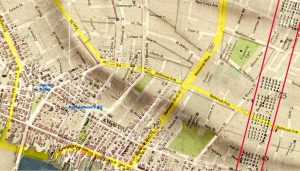

Most of the French maps of Newport seem to be based on the Plan de la position de l’armée françoise autour de Newport et du mouillage de l’escadre dans la rade de cette ville which was apparently made in the autumn of 1780. Some smaller versions of this same map have the signature of Colonel Desandroüins of the Royal Corps of Engineers, but the Library of Congress version does not attribute an author. While the map may have been prepared under Desandroüins’s direction it is likely one of Louis-Alexandre Berthier’s maps because of the similarities in style and technique with other known Berthier maps. Berthier’s journal reveals that he was left behind in France when the army sailed for America. He did not arrive until October 1780. His journal notes that the points marked as landing sites on his maps were his estimation of possible landing sites for an enemy attack.

Why were the French not welcomed upon their arrival?

Newport, the capital and most populous city of Rhode Island, was primarily Loyalist in 1780. Most of the Whigs had fled before or during the British occupation that began in December 1776 and ended in October 1779. The population decreased by half (9,209 in 1774 to less than 5,000). By June 1782, the population increased to only 5,530, including 1,211 African Americans. Most of the refugees had moved to Providence, the second most populous city (4,321 inhabitants in 1774) and to other locations in southeastern Massachusetts. The political, social, and economic centers followed the demographic exodus. Both Newport and Providence had fewer inhabitants than the number of arriving soldiers.

While Newport was considered the capital of the colony, the legislature did not meet in there during most of the Revolutionary war years. Rhode Island had five statehouses—one in each of its five counties. At the end of each session, the legislature decided where and when it would hold its next meeting. It chose Providence as its permanent home only in 1900. The legislature resumed meeting in Newport on July 17, 1780, a week after the arrival of the French army.

The city had been occupied by the British Army for three years. The army was larger than the population and strained the infrastructure. The port was closed to trade with other colonies, destroying the city’s economy. The British occupation ended only seven months before the French arrived and the city was reluctant to host another army. Some historians think that when Newporters realized a fleet was approaching they feared the British were returning, but this is unlikely. Since the majority of the population was Loyalist, they should have had nothing to fear from a returning British army. Moreover, after three years of British occupation, the inhabitants were probably familiar enough with British ships and uniforms to recognize them at a distance. Also, the boats that brought coastal pilots to the arriving fleet would have returned with information identifying it as French.

The French had been the enemy in all the colony’s previous wars, particularly the Seven Years’ War, known locally as the French and Indian War. Many residents had fought in that war and harbored bitter memories. The English had made the French seem odious to the Americans by describing them as the meanest and most abominable people on earth. They said that they were “dwarfs, pale, ugly specimens who lived exclusively on frogs and snails—and a hundred other such stupidities.”[5] Some people even believed the French were “monsters who ate babies.”

The French initially encountered the same prejudices wherever they went. Louis Duportail wrote to Claude Louis, Comte de Saint-Germain on November 12, 1777 to report on the situation in America. The recently promoted brigadier general noted that even though America was at war with Britain, the Americans “hate the French more than they do the English, (we prove it every day), and in spite of all that France has done and will do for them, they would prefer to become reconciled with their former brothers than to have among them crowds of men that they fear more.”[6] Duportail had written a letter to George Washington the previous September about whether he should have his commission renewed or return to France. In it, he said: “if we take up quarters we have to contend for them; the soldiers even offer to take them from us and we have often been forced to drive them out. if we pass before the line, the soldiers who do not love the French, and even some ill-bred officers give us bad language, our servants are insulted, our wagoners are chased from every place and when they mention the names and ranks of their masters they are laught at; thus on public service and in private life we meet with anxieties and mortifications which we can bear no longer.”[7] Duportail also complained that his American subordinate officers and men failed to obey his orders because they wouldn’t take orders from a foreigner.

During the American Revolution, attempts at Franco-American cooperation prior to 1780 were not successful. When the first French officers, such as the Marquis de Lafayette and Louis Duportail and their companions, began to arrive in America, Generals John Sullivan, Nathanael Greene, and Henry Knox wrote to Congress on July 1, 1777 expressing their reservations about French officers commanding American troops. General Sullivan even threatened to resign his commission. Congress responded on July 3, resolving “that the president inform General Sullivan that Congress have not been accustomed to be controlled by their officers in the measures which they are about to take in discharge of the important trust committed to them by the United States; that they mean not to be controlled by his letter in their proceedings . . . for that whatever those proceedings may be, General Sullivan’s resignation will be accepted by Congress whenever he shall think it proper to transmit it to them.”

Congress also directed Washington “to let those officers know that Congress consider the said letters as an attempt to influence their decisions, and an invasion of the liberties of the people, and indicating a want of confidence in the justice of Congress; that it is expected by Congress the said officers will make proper acknowledgments for an interference of so dangerous a tendency; but if any of those officers are unwilling to serve their country under the authority of Congress they shall be at liberty to resign their commissions and retire.”[8]

The first effort at Franco-American cooperation was at the siege of Rhode Island in 1778. General Sullivan was not enthusiastic about cooperating with the French; Admiral d’Estaing (Admiral Comte Jean–Baptiste–Charles–Henri–Hector d’Estaing) also had his reservations about General Sullivan. D’Estaing held commissions as major general in the French army as well as admiral in the French Navy and outranked General Sullivan. He also disliked taking orders from someone he considered an inferior officer. That antipathy, on both sides, increased greatly as the siege commenced. The French troops had landed on Conanicut (Jamestown) Island and were getting re-accustomed to being on land after a long passage. They were drilling when Admiral d’Estaing learned that General Sullivan took possession of Fort Butts a day earlier than agreed upon. He viewed this as Sullivan’s attempt to capture the glories of war. He re-embarked his troops and prepared for battle. A week later, a storm battered the French fleet so badly that it sailed to Boston, the nearest port with adequate repair facilities, leaving the American forces feeling abandoned by their new allies.

Probably most distasteful to Americans was that the French were Catholics. Many colonists came to America to escape religious persecution, particularly from the Inquisition, which was run by the Catholic Church, so they were loath to ally themselves with the French, most of whom were Catholics.

Language was a problem, but not an insurmountable one. Washington did not speak French, but John Laurens, his aide-de-camp, did and served as Washington’s interpreter. Many of the French officers soon learned English well enough to communicate. When the French arrived in Newport, they brought a printing press which reprinted, in French, news items drawn from American newspapers. A Mr. Jastram placed ads in the newspaper announcing that he was offering private lessons in the English language. By the fourth issue (December 8, 1780), he changed the offer from private lessons to group lessons because the demand was so great.[9]

How did General Rochambeau deal with the situation?

Rochambeau immediately began work on defusing his new hosts’ dislikes. He had a proclamation published throughout the countryside assuring safety and protection for everyone.[10] The French soldiers were held to the strictest discipline. French were not allowed out of camp without permission. When a delegation of twenty-two Iroquois, Illinois, and Four Nations Indians arrived at Newport, on August 29, 1780, to visit Rochambeau and the French army, Rochambeau assigned them an empty house in the city and posted two grenadiers at their door to prevent them from going out and alarming the citizens. The Native Americans were amazed that the apple trees in the French camp were full of ripe apples. Any other army would have stripped those trees bare.

The residents of Newport gradually became confident that any abuse would be severely reprimanded and punished. Strict discipline and acts of kindness began to dispel their prejudices to win them over to trust and respect the French. General Rochambeau exerted great gentleness to respect customs which were very different from those of the Europeans. Gradually, both parties learned to tolerate, understand and appreciate the customs of the other.

The French brought wagon loads of money and paid in full for whatever they needed in cash (specie). Specie was in short supply in the American colonies. There were no gold or silver mines yet discovered in the American colonies and Britain did not allow them to mint their own currency. Even though specie was in short supply, Britain required taxes to be paid in specie. The sight of French money increased the interest of shopkeepers, most of whom became greedy. Many French diarists mentioned that they thought they were being taken advantage of because of the difficulties in language, different customs, and the ready availability of cash. Their first purchases cost them dearly, but little by little, the inhabitants provided merchandise in abundance. The army ran out of money before a new supply of 2,500,000 livres arrived (3.5 tons of silver; a livre was a week’s pay for a private soldier) from France. It required fourteen wagons pulled by fifty-six oxen and lead horses to transport the chests of coins.

The French paid rent for their quarters, and repaired, at their own expense, many of the buildings left damaged after the British occupation. They also took over all the houses abandoned by Loyalists who had left the island with British troops, reconditioning them to receive the troops. The officers lodged in private homes. The French spent 20,000 écus on repairs before going into quarters on November 1.[11] The French also repaired and reconstructed many of the surrounding fortifications the British destroyed before their departure.

Many Americans learned French from their guests and the French learned English. The French Navy brought a printing press which was soon set up and began publishing the Gazette Françoise. As only seven issues and a supplement survived, some people think that the subscribers had become so familiar with the English language that the newspaper was no longer needed.

The officers quartered in private homes developed strong friendships with their hosts before departing for Yorktown, Virginia, in 1781, and made a point to renew those friendships on their return from Yorktown in 1782. The final departure to return to France was a very tearful event. Louis Marc Antoine, vicomte de Noailles, Lafayette’s brother-in-law, resided with the Thomas Robinson family. Upon his return home, his wife sent a Sèvres tea service to the Robinson family in gratitude for their fine treatment of her husband.

General Rochambeau had a large hall constructed near his headquarters and paid for a weekly ball to eliminate boredom and to engender goodwill. Sometimes, the officers pooled their funds to pay for a ball. With an army greater in size than the population, this was a grand time for all the women. The regimental musicians probably also gave concerts and the public attended military parades, drills, and even mock battles held at Wood’s Castle.

The eleven-month French occupation of Newport dispelled the myths and prejudices of Rhode Islanders toward the French. The inhabitants made strong friendships with the soldiers, particularly the officers. There were tearful goodbyes when the troops departed on their march south to Yorktown and again upon their return to France.

[1]Armand Charles Augustin de la Croix, Duc de Castries, A Middle Passage; The Journal of Augustin de la Croix de Castries, Duc de Castries, Comte de Charlus and Baron Castries, Sydney W. Jackman, ed. (Boston: The Boston Athenaeum, 1970), 71. This is corroborated by General Rochambeau himself (Henri Doniol, Histoire de la participation de la France à l’établissement des États-Unis d’Amérique. Correspondance diplomatique et documents(Paris: Imprimerie nationale, 1886-1892), 5: 344); Abbé Robin, New Travels through North America; in a Series of Letters …, Philip Freneau, trans. (Philadelphia: Bell, 1783), note iii; Comte Guillaume de Deux Ponts wrote, “we did not meet with that reception on landing, which we expected in which we ought to have had. The coldness and a reserve appear to me to be characteristic of the American nation. They appear to have little of that enthusiasm which one supposes would belong to a people fighting for its liberties, and to be little suited to inspire it in others.” Comte Guillaume deDeux Ponts, My Campaigns in America: A Journal Kept by Count William de Deux Ponts, 1780-81, Samuel A. Green, ed., trans. (Boston: J.K. Wiggin and Wm. Parsons Lunt, 1868), 240; the Count de Lauberdière wrote, “The Count de Rochambeau, as I said, went ashore with Mr. de Béville to reconnoiter a position. He found almost nobody to speak with, no American troops. A Quaker named Mr. Wanton approached him and loaned him some horses and offered him some tea at his house which Mr. de Rochambeau accepted. He asked if the Americans had a commander in town. Mr. Greene, Colonel of the Rhode Island Regiment, who was at Newport with a dozen men was brought to him. He was the first one to whom Mr. de Rochambeau spoke about his mission.” Louis-François-Bertrand du Pont d’Aubevoye, comte de Lauberdière, Journal de l’Armée aux orders de Monsieur le comte de Rochambeau pendant les campagnes de 1780, 1781, 1782, 1783 dans l’Amérique Septentrionale, Archives Nationales, Paris (NAF 17691), Cahier 1, fol. 11 verso.

Mathieu Dumas noted that “We were welcomed with the acclamations of the few patriots that remained in the island, which had lately been occupied by the English, who had been forced to abandon it. Scarcely was the arrival of the French squadron known when the authorities and principal inhabitants in the neighboring country hasten to welcome us.” MathieuDumas,Memoirs of his own Time; Including the Revolution, the Empire, and the Restoration (London: Richard Bentley, 1839), 1: 29. Note that he mentions only a FEW patriots came to greet them. On the other hand, General Heath wrote to General Washington from Newport on July 12, 1780 that “the inhabitants appeared disposed to treat our allies with much respect. The town is to be illuminated this evening, by a vote of the inhabitants. For myself, I am charmed with the officers.” Jared Sparks, ed., Correspondence of the American Revolution(Boston: Little, Brown, 1853), 3: 12. General Heath, however, was not present when the French fleet arrived. He came to Newport only the next day after being summoned by the Comte de Rochambeau.

[2]Lauberdière, Journal de l’Armée, Cahier 1, fol. 17-18.

[3]Jean-François-Louis de Clermont-Crèvecoeur, “Journal of the War in America During the Years 1780, 1781, 1782, 1783,” in The American Campaigns of Rochambeau’s Army, Howard C. Rice and Anne S. K. Brown, ed., trans. (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1972), 1: 17. Abbé Robin confirmed Clermont-Crèvecoeur’s statement: “The arrival of the Army, under M. le Comte de Rochambeau, at Rhode-Island, spread a general terror through that place: the fields became major deserts and those whom curiosity led to visit Newport could scarcely perceive a human form in the street.” Robin, New Travels through North America, 20.

[4]Ezra Stiles, The Literary Diary of Ezra Stiles, Franklin B. Dexter, ed. (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1901), 2: 454.

[5]Clermont-Crèvecoeur, “Journal,” 21.

[6]Louis Duportail to St. Germain, November 12, 1777 in Paul K. Walker et al., Engineers of Independence: A Documentary History of the Army Engineers in the American Revolution, 1775-1783(Washington, DC: Historical Division, Office of Administrative Services, Office of the Chief of Engineers, 1981), 175-177.

[7]Washington forwarded the letter to the President of Congress on September 15, 1777. Papers of the Continental Congress. no. 41, Vol. VIII, ff. 9-10. In English translation signed by Duportail. Elizabeth S. Kite, Brigadier-General Louis Lebègue Duportail, Commandant of Engineers in the continental army, 1777-1783(Washington, DC: Institut français de Washington (D.C.), 1933), 33.

[8]Journals of the Continental Congress, 8: 528, 537. John Sullivan, Letters and Papers of Major-General John Sullivan, Continental Army, Otis Grant Hammond, ed. (Concord, N.H., New Hampshire Historical Society, 1930), 1: 407.

[9]Fellow researchers believe that the newspaper, the Gazette Françoise, ceased publication after number seven and a supplement. However, while translating the journal of Louis François Bertrand Dupont d’Aubevoye de Lauberdière, General Rochambeau’s nephew and aide-de camp, I found issue number 93 inserted in the journal along with other documents. This issue was published in Paris with the same font and printer’s devices as the first issues.

[10]Ordre Avant le Débarquement, Envoyé à Tous les Chefs des Différents Corps.Doniol, Histoire, 5: 341.

[11]Louis Alexandre Berthier, “Journal of Louis-Alexandre Berthier,” in The American Campaigns of Rochambeau’s Army, 1: 236; Clermont-Crèvecoeur, “Journal,” 21-22 n14; Jean Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, Comte de Rochambeau, Mémoires Militaires historiques, et politiques de Rochambeau, Ancien Maréchal de France et Grand Officier de la Légion d’Honneur (Paris: Fain, 1809), 1: 255; Memoirs of the Marshall Count de Rochambeau, M. W. E. Wright, trans. (New York: The New York Times and Arno Press, 1971), 1: 23-24; Sparks, Correspondence of the Revolution, letter dated October 21, 1780.

The French versions of Rochambeau’s memoirs (Mémoires Militaires historiques, et politiques de Rochambeau, Ancien Maréchal de France et Grand Officier de la Légion d’Honneur, 1: 255 and “Mémoire surla Guerrede l’Indépendance des Etats-Unis, à Dater de l’Arrivée du Corps François, 1780, Écrit par Monsieur le Comte de Rochambeau, par Ordre du Ministre, pour le Sieur François Solés, Auteur, etc., etc.” in Collection De Manuscrits Contenant Lettres, Mémoires, Et Autres Documents Historiques Relatifs a La Nouvelle-France, Recueillis Aux Archives De La Province De Québec, Ou Copiés a L’Étranger (Québec:A. Cote Et Cie, 1882-1885), 352, say that the French spent 20,000 écus to repair the buildings. The English translator M. W. E. Wright equates the écu and the livre, saying that the French spent 20,000 livres. An écu was usually worth three livres and sometimes as much as six livres.

4 Comments

Merci, Norm!

Kim

Great article! I lived several years in Newport, and often wondered how the French were accepted. Thanks to them, we won our independence. Vive La France!

Great article. I especially appreciate the Hogarth cartoon, and the map overlay showing the French Camp at Newport in context. With all of your interest in the French, I trust you have seen my JAR article on M Dubuq, First French Officer who served as engineer at Boston in 1775, prior to Washington’s arrival at Cambridge. I have numerous unpublished facts about Boston’s French connections prior to, during and after the Revolution. We have a later Dubuc family member living at Gov. Shirley’s mansion in Roxbury in 1791-3 where Gov. Eustis later entertained Lafayette. I also have documented the capture of French guns in NJ in June 1777.

Intriguing article. The French in America always did have a way with the Natives- although

“Grenadiers were the “special forces” of eighteenth-century armies.”

I’m not sure to what extent a white coat and a tall bearskin cap would have aided covert operations.