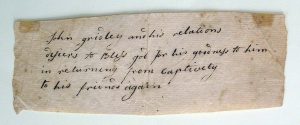

Housed in the Medfield Historical Society is a rare collection of prayer bills containing the prayers of thanksgiving from Massachusetts soldiers and their families during the American Revolution. These commonplace slips of paper include fascinating stories and spiritual requests of ordinary Continental soldiers. One of these late-eighteenth-century prayer notes was written by a veteran named John Gridley. In his prayer bill, Gridley and “his relations” expressed their “desires to Bless God for his goodness to him in returning from captivity to his friends again.” This prayer of thanksgiving contained no particulars describing his “captivity” or how exactly the “goodness” of God was manifested toward him that elicited such a devotional response. Missing from extant genealogies and lists of voters, Gridley and the story behind his prayer note could have lingered in obscurity. Fortunately, however, Gridley’s wife Anna filed a pension application on his behalf in 1843, which filled in the details behind the creation of his prayer bill. Analysis of Gridley’s service in the war and his resultant prayer note provide insight into this Revolutionary soldier’s communal piety and the background of how churches supported their soldiers’ spiritual life during the war.[1]

The only information on Gridley’s background comes from his military records. Based on his pension application, Gridley was born in Roxbury, Massachusetts in the year of 1754 into an unknown family. By April 19, 1775, he was residing in Medfield and joined a company of minutemen under Capt. Sabin Mann. Surviving muster rolls of Gridley’s militia company confirm this first enlistment, in which he was documented with eighty-two other soldiers who marched to Cambridge. Too late for Lexington and Concord, Gridley began combat at Bunker Hill under Capt. John Boyd in Col. John Greaton’s Massachusetts regiment. After this battle, he volunteered to march to Quebec under Col. Benedict Arnold and was among those who fought and were taken prisoner during the Siege of Quebec on December 31, 1775. Gridley continued as a prisoner, enduring much hardship until September 1776; the prisoners in Quebec were put on ships in August and sailed to New York, where they were released by the British at returned to their countrymen in Elizabethtown, New Jersey, in September.[2]

Gridley’s own narrative of his military service was quite extraordinary. Written in 1818, and preserved by his wife, most of Gridley’s statement focused on the hardships he endured on his march to Quebec and his subsequent imprisonment. The journey began in difficulty as he and fellow soldiers “sayl’d” the Kennebec “up, over, and under carring places,” that is, carrying places or portages. It did not take long until their batteaux was “distroy’d” and he was forced to continue the trek by land, all the while suffering “every[thing] but death,” even “the beasts of the wilderness.” It was only “by the assistance of God” that he and his fellow soldiers persevered to St. Roch’s village, in the vicinity of Quebec. The same religious perspective that animated Gridley to write his prayer bill after the war clearly remained with him into 1818, when he recalled his treacherous journey to Quebec.[3]

During the Siege of Quebec, Gridley was among those who were left within the walls of the city and forced to surrender lest they “all be put to death by the sword.” After being captured on December 31, 1775, Gridley sarcastically recalled that “we gave our selves a new years Gift unto General Carleton of Canada, 1776.” The prison they were taken to was bomb proof—with walls and roof thick enough to withstand falling mortar bombs—so he referred to it as a “strong, bumproof prison” where he remained under a “dreafull condition.” The captive patriots did not linger long in that prison before they began to devise ways to escape. Gridley noted that they were not “content,” but “determined for Liberty.”[4]

There were various escape attempts made by prisoners at Quebec, many of which were successful; Gridley’s attempt, however, was not. Gridley and his fellow soldiers “plan’d a skeem to send out to our army, which lay out one mile or two from the city” via a “leter.” The letter requested nearby troops to come and stage an uprising to free the prisoners and take the village. The plan was quite plausible, seeing as prisoners had been successfully passing letters to the troops on the outside. However, Gridley and his conspirators were betrayed. A British man who had been with them in prison “unveiled” their plan to the guards. Fellow prisoner Abner Stocking noted that it was one John Hall who was a deserter from the King’s troops in Boston. But because of this act of loyalty to the British, he was “return’d to his duty.” Immediately after finding out, the prisoners were “handcuft and fastlock’d, two and two together” and kept in that condition until British reinforcements from Halifax arrived in May. His escape attempt failing, Gridley remained in captivity until he was paroled with the other Quebec prisoners that September into New York.[5]

Gridley and his fellow soldiers were immediately recognized for their suffering upon their return to Medfield. By early 1776, the selectmen of that town had already welcomed returning soldiers and voted to reward them with exemption from “poll and highway taxes.” Moreover, Medfield granted and additional six pounds to those soldiers “listed to go to Cannady.” After being honored with such a reception, it was not clear how long Gridley remained in Medfield. Indeed, by the time he wrote his statement in 1818, he was living in New York. However, we know that he continued long enough to submit a prayer bill of thanksgiving to his church community. [6]

These details of Gridley’s military service afford necessary context for analyzing the piety expressed in his otherwise puzzling prayer bill. Conventional in many ways, the most prominent theme in Girdley’s prayer note was his thanksgiving. His “desires to Bless god for his goodness” following his precarious military service illustrated a consistent thread of revolutionary soldiers’ devotional practices. Such pious expressions were particularly common after deliverance from a distressing trial. A similar eulogy ended Pvt. Abner Stocking’s journey home from Quebec: “Never did my thanks to my creator and preserver arise with more sincerity than at this moment. How kind has been that Providence, which has preserved me.” It was his perception of God’s goodness in giving protection during imprisonment that sparked Gridley to submit the prayer bill for thanksgiving.[7]

Girdley’s prayer note was not strictly personal, but was given in and directed for a community, a church. His terminology evidenced the communal emphasis of his request. Gridley did not use theologically fraught language in his prayer bill like “deliverance” from captivity or God having “set me free” after being a prisoner of war, common expressions of other soldiers. Instead, Gridley’s distress was alleviated by his “returning . . . to his friends again.” Who precisely these friends were is unclear, but they presumably were among the members of the church to which he submitted this prayer note. Such emphasis indicated the important communal element in this soldier’s piety. Gridley viewed himself as part of a church that had sent him out and welcomed him again. The solidarity between soldiers and their church community, through mutual petitions and thanksgivings, meant much to Gridley and to those to whom he was returned.[8]

Churches reciprocated the spiritual connection that Gridley and other soldiers felt with them. Other Revolutionary War prayer bills showed that churches often prayed for soldiers in distress. Indeed, a prayer bill submitted by Edward Dorr for his son, William Dorr, who was “in Captivity in Quebec” demonstrated this spiritual concern. Soldiers coveted these prayers from their churches, which gave them comfort during times of service. Indeed, soldiers even prayed for one another, forming a spiritual community within the army itself. When private Samuel Haws heard of the Quebec capture, he was sure to “pray to God thy news may prove falce.” These associations not only comforted soldiers during battle but gave them a context within which to celebrate their return and facilitated their relations with their home communities. Clearly significant for these troops, these spiritual attachments between soldiers and their churches remain underexplored.[9]

John Gridley’s seemingly insignificant prayer bill was all but forgotten about, even by his wife, Anna. Had she known of it, she could have submitted it in his pension application as further evidence of his time of military service. Nevertheless, this small prayer note, placed in the context of Gridley’s harrowing return from Quebec, illustrates important themes of a soldier’s devotional life, one marked by thanksgiving to God for temporal relief, given in the context of a church community.

[1]For background and analysis on the practice of creating and submitting prayer bills, see: Douglas L. Winiarski, “The Newbury Prayer Bill Hoax: Devotion and Deception in New England’s Era of Great Awakenings,” Massachusetts Historical Review 14 (2012), 55-61. I borrow the phrase “prayer of thanksgiving” to describe Girdley’s prayer note from Winiarski. John Gridley, Prayer Bill, n.d. [ca. 1776], Miscellaneous Church Records Collection, Medfield Historical Society (Gridley, Prayer Bill).

[2]Anna Gridley, widow’s pension application #W23137, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files (National Archives Microfilm Publication M804, roll 1130), Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs, Record Group 15, National Archives at Washington, D.C., www.fold3.com/image/1/21464033(Anna Gridley, RWPA); For surviving Massachusetts State House muster rolls, see: William Smith Tilden, History of the Town of Medfield, Massachusetts(Boston: G.H. Ellis, 1887), 165, archive.org/details/historyoftownofm00tild/page/n6.

[5]For complementary accounts of soldiers’ imprisonments and escapes from Quebec, see Caleb Haskell, Caleb Haskell’s Diary (Newburyport: W.H. Huse & Company, 1881), 16; Abner Stocking, An Interesting Journal of Abner Stocking (Tarrytown: Reprinted, W. Abbatt, 1921), 33; Anna Gridley, RWPA.

Recent Articles

Teaching About the Black Experience through Chains and The Astonishing Life of Octavian Nothing

Review: Philadelphia, The Revolutionary City at the American Philosophical Society

Joseph Warren, Sally Edwards, and Mercy Scollay: What is the True Story?

Recent Comments

"The 1779 Invasion of..."

Sorry I am not familiar with it 2 things I neglected to...

"“Good and Sufficient Testimony:”..."

I was wondering, was an analyzable database ever created? I have been...

"Joseph Warren, Sally Edwards,..."

Thank you for bringing real people, places and event to life through...