“Of the forty or more battalions of Loyalists, which enlisted in the service of the Crown during the Revolutionary war, none has been so widely celebrated as the Queen’s Rangers.”—James Hannay.[1]

The Queen’s Rangers, named in honor of King George III’s wife Queen Charlotte, were mustered into service in August 1776 on Staten Island. It was the reincarnation of the French and Indian War unit known as Roger’s Rangers. Colonel Robert Rogers was given authorization by General William Howe to raise a regiment of American Loyalists recruited mainly from New York and Connecticut.[2]

In the summer of 1777, Howe’s army embarked in New York with the goal of capturing Philadelphia. Included in the invasion force was the Queen’s Rangers, consisting of 312 officers and men of whom only 267 were fit for service.[3] The troops boarded their transports on July 9, 1777, but the ships laid at anchor in New York Harbor in the stifling summer heat for two weeks before they sailed. The trip to Philadelphia that should have taken five to six days ended up taking five weeks. Finally on August 26, the Queen’s Rangers disembarked at the Head of the Elk (today Elkton, Maryland) and began their march toward Philadelphia.

Following skirmishes with the Patriot forces beginning on September 1, 1777, the Rangers were assigned to Lt. Gen. Wilhelm von Knyphausen’s column and saw heavy fighting in the Battle of the Brandywine.[4] They experienced significant casualties: twenty killed, ninety wounded and one missing.[5] For their actions at Brandywine, Generals Knyphausen and Howe cited the Queen’s Rangers for bravery.[6] Howe entered Philadelphia on September 26, 1777. The Queen’s Rangers were stationed in the Germantown area when on October 4, 1777, an American attack on this British outpost resulted in the Battle of Germantown.

Following the indecisive action at Germantown, Washington and the Continental Army remained north and west of the city, first at Whitemarsh and then in winter quarters at Valley Forge. The British occupied Philadelphia and stationed their army at eleven strategic redoubts outside the city. The Queen’s Rangers were assigned to the northeast in the village of Kensington, with the responsibility of patrolling up to Frankford Creek along the Bristol Road. Historian Robert I. Alotta described the situation: “though there were no battles fought while the British were ensconced in Philadelphia, there were a number of skirmishes. With all the strength they could muster, the American troops prevented the farmers and market people from coming down from Bucks county to sell their wares to the British. The closest they could get was Frankford.”[7] On October 15, 1777, Captain John Graves Simcoe was given command of the Queen’s Rangers (with the provisional rank of major) and the next day arrived at their at Kensington headquarters.[8]

Simcoe was born on February 25, 1752; his father was a captain in the Royal Navy and succumbed to pneumonia during the assault on Quebec in 1759. Simcoe attended Eton, and spent a year at Oxford before his mother purchased him a commission as an ensign with the 35th Regiment of Foot. In 1774, he purchased a lieutenancy, and in December 1775, he purchased a captaincy in the grenadier company of the 40th Regiment. He saw service during Howe’s New York and New Jersey Campaigns of 1776 and was wounded at the Battle of the Brandywine.[9] Simcoe was one of the young British officers in America (like Patrick Ferguson and Banastre Tarleton) who saw the value of unorthodox irregular military units like the Rangers for service in North America. He stated:

The command of a light corps, or as it is termed, the service of a partisan, is generally esteemed the best mode of instruction for those who aim at higher station, as it gives an opportunity of exemplying professional acquisition, fixes the habit of self-dependence for resources, and obliges to that prompt decision which in the common rotation of duty subordinate officers can seldom exhibit, yet without which none can be qualified for any trust of importance.[10]

During this period, the Queen’s Rangers underwent an overhaul of their organization, received intensive training in partisan warfare, and were involved in a number of skirmishes.

When Simcoe assumed command, the Queen’s Rangers was organized into eight infantry companies, a grenadier company, and a light company; one of the infantry companies was a Highland Company outfitted in full highland garb, including a bagpiper.[11] Simcoe added an eleventh company by assimilating another small Loyalist corps. While at Kensington, Simcoe was offered the services of the 16th Light Dragoons as needed, but instead requested a dozen horses and to mount his own troops. The request was granted and this was the beginning of the Queen’s Rangers Hussars; from this initial group of twelve mounted rangers, it eventually grew to a full company of thirty or more Hussars.[12] Finally, Simcoe was able to acquire a three pound artillery piece, making the Queen’s Rangers a self-sustained fighting force. Like other Loyalist regiments in 1777, the Rangers were outfitted in green coats.[13] In 1778 when it was ordered that all Provincial troops should be outfitted in red uniforms, Simcoe pleaded that the Queen’s Rangers should be allowed to keep their distinctive green uniforms, arguing that the green better served them in the type of operations they were involved. This request was granted and the Queen’s Rangers continued to wear their green uniforms for the remainder of the war.[14]

Also while they were garrisoned in Kensington, Simcoe increased and diversified the training of the Rangers. The Rangers underwent intensive training in the use of the bayonet and target practice to increase their accuracy with muskets.[15] One other change that Simcoe introduced was his emphasis on correct military behavior. He stressed that there was to be no assaulting or plundering of civilians while in camp, on patrol, or on the march. He ensured that guard detachments were always commanded by an officer, so that they were managed with vigilance.[16]

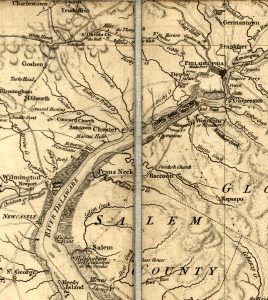

By February 1778, both the Americans at Valley Forge and the British in Philadelphia were seeking to increase their depleted stores of provisions and forage. To meet the needs of the Continental Army, General Washington issued orders for a foraging operation, one of several by both sides called the Grand Forage.[17] Washington appointed Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene as overall commander of the operation. After foraging in Pennsylvania, south and west of Valley Forge (mainly in Chester County), General Greene decided to continue the forage operation across the Delaware River into New Jersey. He ordered Brig. Gen. Anthony Wayne along with two hundred fifty to three hundred men to cross the Delaware, “into the Jerseys from Willmington to execute the design of destroying the Hay and driving in all the stock from the shores.”[18] On February 19, 1778, General Wayne’s force with the help of Capt. John Barry’s sailors crossed the Delaware River, entered New Jersey in Salem County, communicated with Col. Joseph Ellis, commander of the South Jersey Militia, for support and began scouring south Jersey for supplies, particularly cattle and horses.[19]

Wayne’s foraging expedition eventually collected around one hundred fifty head of cattle and thirty horses. Not having a sufficient number of wagons, his men burned the many stacks of hay in the region to keep it out of the hands of the British. On February 25, 1778, situated in Haddonfield, New Jersey, Wayne sent a message to Washington indicating that he was sending the cattle to Trenton and that he was advised that the British had sent around 2,000 troops to New Jersey to stop him and commence their own forage operation.[20]

Loyalists from New Jersey made General Howe aware of Wayne’s expedition. He decided to send two separate units to both trap Wayne and collect livestock and forage for Philadelphia. On February 24, one unit consisting of two battalions of light infantry commanded by Lt. Col. Robert Abercrombie landed at Billingsport, New Jersey (today Paulsboro), went to Salem and began to march north. On the evening of February 25, the second contingent, commanded by Lt. Col. Thomas Stirling (some times spelled Sterling), consisting of the 42nd Regiment, the Queen’s Rangers, and four pieces of artillery (approximately 1000 men) crossed from Philadelphia to Cooper’s Ferry (today Camden). Upon establishing a strong guard at Cooper’s Ferry, the bulk of the 42nd and Queen’s Rangers headed to Haddonfield (approximately nine miles away). An alert New Jersey militiaman spotted the British troops heading to Haddonfield and warned General Wayne who quickly abandoned the town, then marched off to Mount Holly (approximately twenty miles to the northeast).[21]

Upon reaching Haddonfield the Queen’s Rangers encamped along Cooper’s Creek (today called Cooper River) and the next morning received orders to scout to the south. Reaching the Timber Creek they located a number of boats that they intended to destroy, however within these boats were one hundred-fifty barrels of tar that could be used by the British Navy in Philadelphia. At this point, the Rangers came upon a group of Loyalist “refugees” who were willing to take the boats to Philadelphia.[22] On March 1, the Rangers were sent toward Egg Harbor seeking livestock; when about twenty miles from Haddonfield they came upon a building with a large cache of rum and tobacco. It was decided to burn the tobacco but to transport the rum back to camp along with some cattle that they gathered on the march.[23]

That evening, a Loyalist showed up reporting that General Wayne had received re-enforcements and was heading back to Haddonfield. Lieutenant Colonel Sterling, not knowing the size of Wayne’s force, decided it was time to return to Cooper’s Ferry. As they were leaving, a scouting force of Continental cavalry, led by Brig. Gen. Casimir Pulaski, attacked a Ranger outpost.[24] By this time, March 2, Wayne arrived with the rest of his troops, however the British were already returning to Cooper’s Ferry with the Queen’s Rangers providing rearguard protection. Once his entire command was at Cooper’s Ferry, Sterling began sending them back to Philadelphia, again with the rearguard provided by companies from both the Queen’s Rangers and the 42nd. The Patriots began an assault on the position held by the 42nd. While that action ensued, the Rangers noticed cavalry in front of their position and were ordered to advance. Seeing this, the enemy horsemen retreated into the woods except for an officer, perhaps Pulaski himself, who held his ground, waving his scimitar above his head. When the Rangers closed to within about fifty yards, Simcoe called out to the officer, “You are a brave fellow, but you must go away.” When he did not listen to the “suggestion,” Simcoe ordered that he be fired at, after which the rider withdrew.[25]Finally all of the British troops were returned to Philadelphia, with the Queen’s Rangers going back to their garrison in Kensington. Simcoe lamented that a number of Rangers had been wounded and that a sergeant died of his wounds during their time in New Jersey. However he further noted that Colonel Sterling made a very favorable report on their behavior to General Howe.[26]

As a final postscript to this “Continental foraging operation” the following appeared in the New Jersey Gazette: “About three weeks ago, a number of cattle having been sent from this state, intended for our camp, the enemy, getting intelligence thereof, and by the assistance of the Tories, way-laid and took them, with several of the guard, in Pennsylvania, about 16 miles from Philadelphia.”[27]

After only ten days back at their post in Kensington, the Queen’s Rangers were again on another foraging expedition in New Jersey which included another Loyalist regiment, the West Jersey Volunteers,[28] and three British infantry regiments, the 17th, 27th, and 46th. This force of about 1200 men was under the overall command of Lt. Col. Charles Mawhood.[29] The plan of the mission was to forage in Salem and Cumberland counties. Departing aboard transports on March 12, they arrived off of the mouth of Salem Creek on March 16.[30] Early in the morning of the March 17, the Queen’s Rangers force of two hundred seventy infantry and thirty Hussars disembarked with a mission to scour the countryside to secure horses. Simcoe reminded his troops there would be no plundering of the locals and to inform the citizens whose horses were taken they would be returned or paid for when they left, but only if they were not rebels.[31] Upon a successful completion of their mission, the Rangers rendezvoused with the main British force, which had occupied the town of Salem.

With Salem serving as the British base of operations, foraging began both north and south of the town. To the south of Salem the first natural barrier was Alloways Creek (at the time also spelled Aloes or Alewas). The tidal Alloways Creek extends approximately thirty miles inland, and was crossed by three bridges: Hancock’s (closest to the Delaware), Quinton’s (middle) and Thompson’s (furthest east). Patriot militia units from both Salem and Cumberland Counties took up defensive positions on the southern side of the bridges and dismantled them by removing planks. Particular attention was given to Quinton’s and Hancock’s Bridges. On March 18 three British foraging parties were sent out in search of cattle, one north toward Penn’s Neck (today Pennsville) and the other two headed for Quinton’s and Hancock’s Bridges. At Hancock’s Bridge, the American militiamen had successfully dismantled the deck of the bridge making crossing it almost impossible, so the British did not attempt to cross at this point. However at Quinton’s Bridge it was a different story.

About seventy men from the 17th Regiment got to Quinton’s Bridge, where they came upon a large contingent of militiamen in strong defensive positions along the creek. Calling for reinforcements, both Mawhood and Simcoe arrived on the scene to judge the situation. Accompanying them were the Queen’s Rangers, who took a circuitous route so that the militia would not know of their presence. The commanders devised a plan to entice the militia to leave their defensive lines and come across Alloways Creek. The 17th Regiment patrol feigned an attack on the bridge and then quickly retreated. Simcoe had a company of Rangers hide in a house near the bridge, with the bulk of the regiment taking up a position in nearby woods. At the instigation of a French officer, Lt. Francis Dulcos, the New Jersey Militiamen took the bait and charged across the bridge after the retreating British.[32]

Once the militia passed the house and neared the woods the trap was sprung, taking them by complete surprise. This led to panic, and the militiamen began running for their lives back to the bridge. In the ensuing fight anywhere from thirty to forty militiamen were believed to have been killed, with a number drowning in the creek trying to swim back to their lines.[33] Following this rout, more militia arrived on the scene. Mawhood decided no good would come from crossing the bridge and the entire British force returned to Salem.[34] For the next few days the British continued their foraging north of Alloways Creek with cattle and hay being sent back to Philadelphia. On March 20, 1778, Mawhood decided it was time to teach the militia another lesson and an attack on Hancock’s Bridge was planned.

The plan called for the Queen’s Rangers to row down Alloways Creek out of sight of the militia, cross to the southern bank and then head back to the bridge. At the same time, coming from Salem was a contingent of the 27th Regiment, who positioned themselves on the north side of the bridge to await the arrival of the Rangers. The main objective of the Rangers’ attack, aside from the bridge, was the Hancock House, located just to the southwest of the bridge. On the property were a number of storehouses and cottages. It was reported that there were up to 400 militiamen in the area and that the bulk of the defending force would be found on this property.[35] Simcoe believed that the success of the operation depended on taking the militia by surprise. So the plan called for a simultaneous attack at the house by two companies of Rangers coming through the front and back doors, using only bayonets, with the remainder of the regiment attacking the storehouses and cottages. Finally, one company was assigned the task of securing and laying down the dismantled bridge planks so that the waiting 27th Regiment could cross the creek.[36]

After crossing the Alloways near its mouth, the Rangers used a local Loyalist guide and then slogged through the marshlands back to the bridge and the Hancock House. They silently dispatched two sentinels and then stormed in the house, taking the sleeping militiamen by complete surprise. Inside the house were twenty or so men including the owner, Judge William Hancock, and his brother, whom Simcoe described as friends of the “Government.”[37]

Historian James Hannay described the action:

Capt. Dunlop’s and Stephenson’s companies attacked those in the house with such fury that every man in it was killed. This was a lamentable occurrence and has enabled American writers to assert that these men were massacred, but it must be remembered that it was a night attack and that Simcoe’s Rangers, instead of this insignificant detachment, expected to meet a force of at least 700 or 800 men, and, of course, a desperate resistance was expected.[38]

The result of the bayonet attack was that all inside the house were killed, wounded or taken captive. This became known in Revolutionary War history as the “Hancock House Massacre.”[39]

When the planks were laid down, the 27th crossed over, led by Lt. Col. Edward Mitchell who was in overall command. Simcoe urged that they proceed to Quinton’s Bridge and take the militia there by surprise. Mitchell initially did not want to take this action but was reconsidering when a militia patrol from Quinton’s Bridge came on the scene and raced back to give the alarm. For Mitchell, this development settled the question and the entire force returned to Salem. The British had only one casualty, the death of a Ranger Hussar. This was reported in the Loyalist Pennsylvania Ledger on March 25, 1778: “The King’s troops have lost only one man killed since their going into the Jerseys: He was of the Queen’s Rangers, and behaved gallantly in a skirmish with the militia, who have had twenty men killed on the spot, and ten prisoners taken, with a French Lieutenant on the recruiting service.”[40]

One result of the “massacre” was an exchange of letters between Lt. Col. Mawhood and Col. Elijah Hand of the Cumberland Militia. Mawhood called for the militia to lay down their arms and allow the British to continue with their foraging unmolested. If they did this there would be no further bloodshed and when they left they would pay for all that was taken. However, he warned that if there were continued resistance the “rebels” would pay a severe price for their actions and listed seventeen rebels leaders whose property would be destroyed.[41] Colonel Hand replied that they would never lay down their arms in face of such brutality, equating the British with Attila.[42] Between March 21 and 26, the British continued their foraging in the area, while the militia abandoned their positions along Alloways Creek, moved south, and set up a new defensive line on the south bank of Cohansey River, protecting the approach to Cumberland County and the town of Bridgeton.[43]

By March 26, all the collected forage, including 300 tons of hay, large quantities of corn, grain, and cattle, had been shipped back to Philadelphia. While this was taking place, Simcoe recommended that they should attack the rebel lines on the Cohansey, but Mawhood vetoed the idea, stating it would serve no purpose.[44] All the British forces left Salem, arriving back in Philadelphia on March 30, 1778, with the Queen’s Rangers returning to their base at Kensington, again resuming their patrols along the Bristol Road. Before the British evacuation of Philadelphia in June 1778, the Rangers were involved in another large raid, this time an attack on Pennsylvania Militia known as the Battle of Crooked Billet. Following the evacuation of Philadelphia, the Queen’s Rangers further left their mark in New Jersey from their actions in the Battle of Monmouth; then with a number of incursions into the state from their headquarters on Staten Island, before they were eventually sent to Virginia in 1780.

[1]James Hannay, “History of the Queen’s Rangers,” From: Transaction of the Royal Society of Canada, Third Series – 1908-1909, Vol. II, Section II, edited by John Chancellor Boylen, 124. (Found at archives.com) This regiment was also referred to as the Queen’s American Rangers. On May 2, 1779 they were designated the Queen’s Rangers, 1st American Regiment.

[2]While it is not in the purview of this article to present of the life of this interesting and controversial figure in American colonial and Revolutionary War history, the reader is encouraged to see: The Annotated and Illustrated Journals of Robert Rogers, Timothy J. Todish, annotator (Fleischmanns, NY: Purple Mountain Press, 2002); John F. Ross, War on the Run: The Epic Story of Robert Rogers and the Conquest of America’s First Frontier(New York: Bantam Books, 2009); Stephen Brumwell, White Devil: A True Story of War, Savagery, and Vengeance in Colonial America(Cambridge, MA: DaCapo Press, 2004).

[3]Donald J. Gara, The Queen’s American Rangers (Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, 2015), 60. For a review of Gara’s book see: Jim Piecuch, Journal of the American Revolution, September 15, 2015.

[4]For a good overview of the battle at Brandywine, see David G. Martin, The Philadelphia Campaign June 1777 – July 1778 (Conshohocken, PA: Combined Books, 1993.)

[5]Gara, Queen’s American Rangers, 76.

[6]James Hannay, “History of the Queen’s Rangers,” 128.

[7]Robert I. Alotta, Another Part of the Field: Philadelphia’s American Revolution, 1777-1778 (Shippensburg, PA: White Mane, 1991), xii.

[8]Following Rogers’ dismissal and before Simcoe, the Queen’s Rangers were commanded by Maj. Christopher French and Maj. James Wemys.

[9]For more information on John Graves Simcoe’s life before and after his service with the Queen’s Rangers see David Read, The Life and Times of General John Graves Simcoe(Toronto: G. Virtue, 1890); Mary B. Fryer and Christopher Dracott, John Graves Simcoe 1752 – 1806: A Biography(Toronto: Dundurn Press, 1998).

[10]John Graves Simcoe, Queen’s Rangers: John Simcoe and his Rangers During the Revolutionary War for America (United Kingdom: Leonaur Publishing, 2007 reprint), 1-2. It is interesting to note that Simcoe, like Julius Caesar, wrote his memoir in the third person singular.

[13]In some depictions of the Queen’s Rangers they are shown wearing tall black caps; these were adopted by their Hussar Company due being mistaken for Continental dragoons. See Brief History of the Queen’s Rangers 1776-83, www.queensrangers.co.uk.

[14]John Mollo, Uniforms of the American Revolution, Malcolm McGregor, illustrator (New York: Sterling Publishing, 1991, illustrations: 179 (Hussars), 183, 184, 185 (Infantry), descriptive text, 211- 213.

[15]Simcoe, Queen’s Rangers, 18.

[17]For an excellent article on this subject see: Ricardo A. Herrera, “Foraging and Combat Operations at Valley Forge,” Army History: The Professional Bulletin of Army History, Spring 2011, PB 20-11-2 (No, 79). Washington, DC, 6-29. It can be found online through academia.edu. Another “Grand Forage” took place in September 1778 around New York City; for details see Todd W. Braisted, Grand Forage 1778: The Battleground Around New York City (Yardley, PA:Westholme Publishing, 2016).

[18]Herrera, Foraging and Combat, 16.

[19]For an amusing description of this “Jersey Cattle Drive” see: Susan Kaufman, “America’s first cattle drive? Salem County’s Great Cow Chase,” Hidden New Jersey, July 8, 2015, found at hiddennj.com. This operation should not be confused with Major John Andre’s poem The Cow Chaceabout another cattle drive that General Wayne took part that occurred in North Jersey, July 1780. For an overview of this action see: Battle of Bull’sFerry, at revolutionarywar.us

[20]For a detailed description of General Wayne’s action on this expedition see: “To George Washington from Brigadier General Anthony Wayne, 25 February 1778, and 26 February 1778.” For Washington’s reply and orders to Wayne, see: “From George Washington to Brigadier General Anthony Wayne, 28 February 1778,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified June 13, 2018, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-13-02-0566. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 13, 26 December 1777 – 28 February 1778, ed. Edward G. Lengel. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2003, pp. 668–671.]

[21]Herrera, Foraging and Combat, 20. Also, Founders Online, “Letter Wayne to Washington, 25 February 1778,” fn. 5.

[22]Simcoe, Queen’s Rangers, 37.

[23]Gara, The Queen’s American Rangers, 104.

[24]For detailed description of the events at Cooper’s Ferry, see: Simcoe, Queen’s Rangers, 41-42. For details from the American version: “To George Washington from Brigadier General Anthony Wayne, 5 March 1778,” Founders Online, National Archives; also a translation of Pulaski’s French letter to Washington concerning the events at Haddonfield and Cooper’s Ferry, see: Martin J. Griffin, Catholics and the American Revolution (Philadelphia: Self Published, 1911), 3:50-51. Griffin’s Catholics can be found online at archives.org.

[25]Simcoe, Queen’s Rangers, 42.

[26]The West Jersey Volunteers did not participate in the actual foraging expedition; they were dropped off at Billingsport, NJ north of the area of operations to serve as a blocking force should the Patriots send troops from Burlington County.

[27]New Jersey Archives Newspaper Extracts – 1778, 2ndSeries, v. II Francis B. Lee, ed., Trenton: 1903, 117. Found on line at archives.org.

[28]Simcoe, Queen’s Rangers, 43.

[29]It took four days to travel the approximate forty miles between Philadelphia and Salem.

[30]For photographs and descriptions of Quinton and Hancock Bridges, see: www.revolutionarywarnewjersey.com/salem

[31]He was attached to Colonel Israel Shreves’ 2ndNew Jersey Continental Regiment.

[32]Gara, The Queen’s American Rangers, 112.

[33]Gara, The Queen’s American Rangers, 114.

[34]Simcoe, Queen’s Rangers, 46.

[36]Simcoe, Queen’s Rangers, 48.

[37]Simcoe noted that the information they had was that Judge Hancock didn’t live at the house since the “rebels” took possession of the bridge; that was partly true, he was not home in the daytime but spent the nights there. Simcoe, Queen’s Rangers, 48.

[38]Hannay, “History of the Queen’s Rangers,” 141.

[39]Simcoe, Queen’s Rangers, 48, stated, “twenty or thirty men, all of whom were killed.” The actual number of casualties is still unknown, but British Military Engineer, Archibald Robertson, who was on the expedition to Salem, recorded in his journal that the final tally was sixteen killed and eleven taken prisoner, see “The Making of a ‘Massacre’: Simcoe’s Surprise Attack at Hancock’s Bridge,” posted August 16, 2017, at 17thregiment.com.

[40]Francis B. Lee, ed. Archives of the State of New Jersey, Second Series, Vol. II, “Documents Relating to the Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey / Extracts from American Newspapers relating to New Jersey,” (Trenton: John L. Murphy Pub. Co. 1903), 133. Found online at archives.org. (Note: the “French Lieutenant taken,” was the previously mentioned Lieutenant Duclos. Also see Gara, The Queen’s American Rangers118.

[41]Francis B. Lee, ed. Extracts from American Newspapers relating to New Jersey Archives, 168.

[42]To see Colonel Hand’s complete reply, see: “Col. Elijah Hand to Col. Charles Mawhood,” Publication of New Jersey Historical Society, ser. 1 (1858), 8: 100-101. Found at www.njstatelib.org/…/NJ…Collections/NJInTheAmericanRevolution.

[43]Gara, The Queen’s American Rangers, 119-120.

[44]Simcoe, Queens Rangers, 50.

2 Comments

The commander of the 42nd Highlanders for most of the American Revolution was Lt. Col. Thomas STIRLING, Younger of Ardoch. The spelling Sterling is a common mistake of both the 18th and 21st centuries. His biography and a copy of his signature confirming the correct spelling can be found at my website: Kilts& Courage, The Story of the 42nd or Royal Highland Regiment in the American War for Independence, 1776-1783 on Vol. II, Biographies N-Z on page A-379 at : https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/3e08bf_0dd0e2384a5e4614b9ee1f59a22cb863.pdf

Account of Lt. Col. Thomas Stirling’s Raid by Capt. Lt. John Peebles, 1st Battalion, 42nd Regt., Haddonfield, New Jersey, Feb. 25 – Mar. 2, 1778

Wednesday 25th. Febry. the weather remarkably mild & soft – last night the two battalions of Light Infantry [including the 42nd Lt. Inf. Company] cross’d over to the Jersey – the 42d. & [Maj. John Graves] Simcoes Corps [Loyalist Queen’s Rangers] are to go tonight

Thursday 26th. Febry. the 42d. & the Queens Rangers cross’d the Delaware [River] last night about 12 oclock & landed at Coopers island above the ferry house we march’d immediately to the ferry Wharf where the Guns (4 three pors [pounders]) were to land, but they held off some time on accot. of a few shot fir’d at them by a guard of militia that were at the ferry house and who ran off on our coming up these things got ashore the Detachmt. proceeded with their Guns leaving a Field officers Guard [approx. 150 men] to come up with the Waggons, we march’d to the eastward thro’ dirty road & arrived at Haddonfield about sunrise, where it was expected we should have fallen in with [Rebel Brig.] Genls. [Anthony] Wayne [Pennsylvania Line] and [Col. Joseph] Ellis [Haddonfield Militia] who had a Detachmt collecting Cattle for the Rebel Army, but they had got previous notice of our coming as they left Haddonfield last night about 11 o’clock & entirely evacuated the Village of troops which had been occupied by the Militia all the Winter, to keep the people from supplying the Philada Market, which the states have made felony by their Laws, the Village contains about 40 families mostly Quakers who seem to be heartily tired of this Contest – On finding the rebels had gone so long before we came, 7 the day rainy Colol. Stirling order’d the men into barns & placed Guards about the Village. the offrs. went into the inhabitants houses, who seem’d well pleased at our coming –

Saturday 28 sharp frost last night …

Sunday 1st. March fine clear weather with gentle frost in the night…a Detachmt. of ours went out to the NW to bring in forage…The Light Infantry still in the jersey down below Billingsport or Salem…

Monday 2d. March yesterday evening the Coll. got some intelligence of a great Body of the Enemy coming towards us & some shots being fired at the rangers Pocket across the Creek at Keys Mill the Compys. order’d under arms, & soon after desir’d to go into the Barns & be ready to turn out at a moments warng. it then came on to snow; about an hour or two after we were turn’d out again & march’d off by the left to Coopers ferry where we arrived about two oclock in morng. exceeding cold, most of the men got under cover the rest made fires – the morng. was very storm & boats could not get over, about noon some of the Rebel light horse seen at the edge of the wood which occasion’d us to turn out – but they went off – however a few hours after a Body of Horse & foot came down and attack’d our Picquets in which we immediately stood to our arms & moved up to them, a short skirmish ensued and they ran off – 3 men of ours & 3 or 4 of the Rangers wound’d we pursued them a mile or two & returned to the ferry where we Embarked, cross’d & got to Quarters about 8 oclock – the Light Infantry return’d yesterday without seeing the enemy

Source: NRS, Peebles Journal Entries for Feb. 25-Mar. 2, 1778 and published in John Peebles’ American War, Ed. Ira Gruber, Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania, 1998, pp. 165-166.