As November 1780 begins, we find Cornwallis continuing to wait at Winnsborough, South Carolina, in the hope of being joined by Major Gen. Alexander Leslie, a junction on which the winter campaign to the northward depended.

Bound for the Chesapeake and placed under the orders of Cornwallis, Leslie had sailed from New York on October 16 with a medley of some 1,900 troops and entered Hampton Road six days later. The principal objects of his expedition were to cooperate with Cornwallis, make a diversion in his favor, and establish a post on Elizabeth River. Complying with Cornwallis’s tentative summons to join him, he did not quit the Chesapeake before November 22 and it was not till December 13 that he arrived off Charlestown[1] bar. His reinforcement, which was inadequately composed, required some remodelling on landing.

Born in 1731, Leslie was a younger son of the Earl of Leven and Melville. Entering the army in 1753 as an ensign in the 3rd Regiment of Foot Guards (the Scots Guards), he had risen by 1768 to the lieutenant colonelcy of the 64th Regiment stationed at Boston. In 1776 he played a prominent part as a brigadier general in the New York campaign and in 1780 had come south with Sir Henry Clinton, having been promoted to the local rank of major general. On conclusion of the Charlestown campaign he returned with Clinton to New York.

After taking part in the winter campaign and the march to Virginia, he was—in late July 1781—appointed by Cornwallis to command at Charlestown and was notified at the same time of his promotion to the local rank of lt. general. He did not sail for Charlestown directly but called first at New York, where he participated in the councils of war convened in response to the developing crisis in Virginia. He did not reach Charlestown till November. With the fate of the war then decided, he proceeded to evacuate the town and Savannah in 1782, a year in which he was promoted to the regular rank of major general.

Leslie’s end came at Beechwood House about three miles west of Edinburgh. As second in command in Scotland, he had been involved in suppressing a mutiny among fencible troops at Glasgow, where he was knocked down by a missile thrown by a riotous mob. On his way back to headquarters he became dangerously ill and died on December 27, 1794. His remains are interred in Jedburgh Abbey. A portrait of him by Gainsborough is in a private collection surveyed by the Scottish National Portrait Gallery in 1964.

Now arriving in Charlestown, shortly before Leslie, was Brig. Gen. Charles O’Hara (c.1737-1802), who was to command the Brigade of Guards forming part of Leslie’s reinforcement. Comprising 750 men, it consisted of three detachments from the Grenadier, Coldstream, and Scots Guards.

An illegitimate son of Lord Tyrawley, O’Hara was educated at Westminster School before being appointed a cornet in the 3rd King’s Own Regiment of Dragoons in December 1752. Some three years later he was promoted to a lieutenancy in the Coldstream Guards, seeing service in Portugal and Germany during the Seven Years’ War. He went on to become lieutenant colonel of the Africa Corps of Foot and Governor at Senegal, where he remained till dismissed from the Governorship in 1776. Meanwhile he had been promoted to captain in the Coldstream Regiment, a rank which carried with it a lieutenant colonelcy in the rest of the army. Coming out to North America at the beginning of 1777, he was eventually promoted by Clinton to the local rank of brigadier general but played a relatively inconsequential part in the war. Returning home on leave in February 1779, he had arrived back at New York in October 1780. He would now go on to distinguish himself for courage and leadership in the winter campaign, being severely wounded at the Battle of Guilford.

O’Hara was a friendly, larger-than-life character with immense charisma and charm, described by his contemporaries as handsome with a dark and ruddy complexion, a facile tongue, and a ready grin. It would fall to his lot to deliver up the troops at Yorktown after Cornwallis feigned a temporary indisposition. Wounded and captured in 1793 by the French at Toulon, he would die a full general while Governor of Gibraltar, beset in his final months by illness and constant pain from old war wounds. “Few men,” according to The Gentleman’s Magazine, “possessed so happy a combination of rare talents. He was a brave and enterprising soldier, a strict disciplinarian, and a polite accomplished gentleman.”

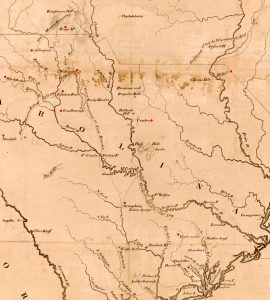

While Leslie was awaited at Charlestown, all possible means were employed to put South Carolina into a better state of defense, but it was an uphill, largely unrewarding struggle. Yes, the navigation of the Santee was secured, enabling the safe conveyance of supplies to Camden and Winnsborough, yet despite the quiescent effect of Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton’s brief incursion in early November, the vast territory east of the Wateree and Santee remained almost totally outside British control. Admittedly, a small garrison occupied Georgetown, the 64th and other troops operated between Nelson’s Ferry and Camden, and Col. James Cassells’ militia regiment was advanced to Black River, but neither they nor Tarleton, outside their immediate areas of operation, had a material effect on this virulently disaffected region, the hunting ground of Lt. Col. Francis Marion.

A principled man of short, unprepossessing appearance, Marion, unlike Brig. Gen. Thomas Sumter, was opposed to plunder and wanton cruelty, impressing on his men to forgo such activities. Yet as volunteers they could come and go as they pleased. Once away from camp they “found it difficult to stifle the strong urge for vengeance and often satisfied their blood lust on those loyalists who were so unfortunate as to meet up with them.” These poor creatures were “chased from their homes, hunted thro’ the woods, and shot with as much indifference as you would a buck.” Their possessions were rifled.

By the start of November 1780 the situation in the Low Country to the west of the Santee had also begun to deteriorate. So many small parties of revolutionary irregulars were entering the territory from the east, crossing the river above and below Nelson’s Ferry, that Lt. Col. Nisbet Balfour, the Commandant of Charlestown, was obliged to detach fifty men to Monck’s Corner with orders to move on to Nelson’s if necessary, despite there being already very strong posts at both locations. The ferry at Manigault’s he directed to be secured by Col. John Fisher’s Orangeburg militia, and those on the lower parts of the Santee by the militia of Cols Elias Ball Sr and John Wigfall, but no assistance was forthcoming from the militia of Cols Nicholas Lechmere and Robert Ballingall, who were totally disaffected and refused to turn out to a man. Together with the move of the 64th and other troops to the eastern side of the river and the posting of an additional 120 Hessians and convalescents at Monck’s Corner, these measures appear to have stabilised the situation, though the threat of incursions remained.

In the Back Country the post at Camden was initially in much need of improvement. When Col. Francis Lord Rawdon arrived on November 13 to supersede Lt. Col. George Turnbull, he found matters in so backward a state that he anticipated some difficulty in making the post tolerably convenient and pretty secure before the bad weather set in. As the village was by no means capable of holding the number of men who required quarters in it, he promptly sent for a quantity of planks and boards so that barns, stables etc. might be speedily converted into some kind of barracks for the troops and huts erected for the officers. By the close of November the redoubts, though defensible, were by no means completed, while arrangements were in train for constructing a strong log house to defend the mill and for putting up a stockade around the body of the village, which would secure the stores. By the close of December Rawdon had laid up a sufficient stock of provisions to support the garrison for many days in case he was reduced to keeping close within the works, and was continually adding to the hoard by collecting more than was necessary for the garrison’s immediate consumption.

In a dispatch to Cornwallis of November 25 Rawdon goes some way towards amplifying what he would many years later assert were the extraordinary disadvantages which attended Camden as an individual position: “Should the enemy approach in such force as to make me confine myself to the works, the village and stores might be burned without my being able to prevent it. The principal redoubts are so far asunder that resolute troops would pass between them at any time without hesitation and the most timorous might penetrate by night without apprehension. The works likewise, tho’ defensible, are by no means complete. In short, the post (which was always an infamous one) is not much mended by the entrenchments in their present state, but I will venture to promise that, should the foe attack us, your Lordship shall be satisfied with our behaviour.”

Garrisoning the village on Rawdon’s arrival were the 7th Regiment (Royal Fusiliers), New York Volunteers, the Royal North Carolina Regiment, the South Carolina Royalist Regiment, and the Volunteers of Ireland. If we allow for the sickness prevalent among them, the rank and file present for duty amounted in all to approximately 1,050 men, to whom should be added Major John Harrison’s irregulars and 150 convalescents fit for the defense of the redoubts. On November 25 the 7th Regiment was dispatched to reinforce Cornwallis and one day later Rawdon assured him, “Should the enemy attempt this post, I hope they will find neither want of vigilance nor of firmness in the garrison.” On December 5 the 63rd arrived to replace the 7th.[2]

As the enemy nearly always kept at a distance in his front, Rawdon was able to push frequent detachments through the districts around him, which greatly checked any growing combinations. At the close of December he was confident, that, by fitting out a part of the New York Volunteers as cavalry, he would enable his force to acquire a more active quality.

Some 30 miles west-north-west of Camden lay Winnsborough, the post occupied by Cornwallis. With him at first were 600 men composed of the 23rd, 33rd, and 2nd Battalion, 71st Regiments, to whom, as previously related, were soon added the remnants of the 7th, which had been much depleted by illness. Major Archibald McArthur with the 1st Battalion, 71st, had earlier been detached to the eastern bank of Brierly’s Ferry, where he arrived on November 12. It was situated low down on Broad River some sixteen miles west-south-west of Winnsborough. With orders to watch the motions of the enemy and secure the communication with the mills he remained in its vicinity till early January, apart from a brief excursion to join Tarleton after the action at Blackstocks. From the beginning of December the British Legion lay close by.

Together, the posts at Brierly’s, Camden, and Winnsborough effectually secured the lower part of the territory between the Broad and Catawba or Wateree Rivers, but no control was exercised over the mid to northern part, where the enemy was free to operate.

West of the Broad River the situation remained precarious. By the beginning of November the whole of the country to the north of the Enoree was in the enemy’s possession, and despite the actions at Fishdam Ford and Blackstocks it remained preponderantly so. Between the river and the Saluda was only one post, Williams’s stockaded house, which was occupied first by Lt. Col. Moses Kirkland with 100 of his militia, and then by Brig. Gen. Robert Cunningham with 200 or so of his. On December 30 Cunningham evacuated the house after the enemy routed a party of militia seven miles above. As a result control of the remaining territory between the Enoree and Saluda was lost.

From the Enoree to Long Cane few of the royal militia had been willing to turn out, and of those that did, many were ill equipped and short of arms and ammunition. Almost all were dispirited and could not be relied on. Yet, exceptionally, a party of some 210 had performed well when they participated with Lt. Col. Isaac Allen and 150 rank and file of the Ninety Six garrison in routing Lt. Cols Elijah Clark and James McCall near White Hall on December 12.

Continuing to occupy the village of Ninety Six were the 1st Battalion, DeLancey’s Brigade, and the 3rd Battalion, New Jersey Volunteers, under the overall command of Lt. Col. John Harris Cruger. Near 300 men were fit for duty. By December 9 the extensive fortifications were well nigh complete, at which time Lt. Henry Haldane, an engineer, reported to Cornwallis, “I arrived at this place on Wednesday morning and found the works in a much better state than I expected. Tho’ they are not so entirely conformable to rule, yet they may answer the present purpose as well as the best executed work.” He recommended that an abatis be constructed, which was promptly begun. The artillery to be kept by the garrison was for a time uncertain, but on January 4 Haldane confirmed that its two field pieces were to remain and that an iron 6-pounder had been ordered up. The problem, if the post was besieged, would be the want of water.

Although Allen—Cruger’s second—took part in two brief excursions, the post was fit for little more than a bare defensive. To detach troops in force that could keep the field a reinforcement was necessary, a fact recognized by Cornwallis when he assigned the 7th to Cruger’s command at the beginning of January. It comprised 167 rank and file. In addition Major James Dunlap was busy at Ninety Six in forming two or three troops of 40 loyalist dragoons each. Unfortunately, while the 7th were on their march to join the garrison, they were temporarily placed under Tarleton and captured at the Battle of Cowpens. They were not replaced.

Having obtained leave of absence from Cornwallis, Cruger departed on December 17 or 18 for Charlestown, where he arrived on the 21st. It was not until January 9 that he set out on his way back.

Immediately south of the Congaree was the post which became known as Fort Granby. It appeared to Balfour of great importance. Writing to Cornwallis on December 26, he remarked, “. . . if I receive no orders to the contrary [and he received none], shall immediately send up Mr [Andrew] Maxwell there and give him sixty of Brown’s corps[3] and one hundred of the Orangeburgh militia, which are forming upon the new plan and in which I have confidence. A redoubt round Hampton’s house with this garrison will not be forced except by cannon and can act offensively against small partys. The ferrys over the Congarres and Saluda will be covred by this post, as also the communication betwixt Camden and Ninety Six and the District of Orangeburgh, which induces me to wish it as strong as possible.”

On December 17 Balfour set out for Winnsborough, where he arrived late on the 20th. While there, he settled with Cornwallis a mass of business too extensive to be dealt with in correspondence. He arrived back in Charlestown on the 28th.

Busy in the Back Country on the enemy side were a number of actors. Sumter, who on October 6 had been formally commissioned a brigadier general of militia, now returned to the fray. At the beginning of November he advanced to the east side of Broad River with several hundred men and, while posted at Fishdam Ford, was surprised in the early hours of the 9th by Major James Wemyss[4] and a party of the 63rd and British Legion. It was an inconclusive engagement, but due to the inexperience of a junior officer Wemyss, who was wounded in the initial attack, was captured and paroled together with a number of his wounded men. Crossing to the west side of the river, Sumter claimed a victory, was widely believed, and many flocked to his standard, increasing his command to reputedly 1,000 men. Among field officers in the vicinity were Thomas Brandon, James McCall, William Candler, Elijah Clark, John Thomas Jr and John Twiggs, who united under Sumter in repulsing Tarleton on November 20 in the action at Blackstocks. Of Tarleton’s men some 50 were killed or wounded, while the enemy’s casualties came to only seven. If it had not been that Sumter was severely wounded, the affair would have been rightly classed as an enemy victory.

Besides the actions at Fishdam and Blackstocks, the behavior of the revolutionaries toward the loyalists and uncommitted was equally important in their retaining control of most of the territory beyond Broad River. Not to put too fine a point on it, a reign of terror was instigated. On November 23 Cornwallis, who had no reason for lying to a subordinate, advised Cruger that Sumter’s men “have been guilty of the most horrid outrages.” Not only was Sumter responsible but also Brandon, Clark and others, who, as Cornwallis explained on December 3 to Clinton, “had different corps plundering the houses and putting to death the well affected inhabitants between Tyger River and Pacolet.” Next day he observed to Clinton, “I will not hurt your Excellency’s feelings by attempting to describe the shocking tortures and inhuman murders which are every day committed by the enemy, not only on those who have taken part with us, but on many who refuse to join them . . . I am very sure that unless some steps are taken [by the enemy] to check it, the war in this quarter will become truly savage.” The upshot was of course inevitable, as Cornwallis stated on November 17 to Balfour: “our friends terrified beyond expression, either flying down the country or submitting tamely to the insults and cruelties of the enemy, all the disaffected and many who had been neutral and some pretended friends flocking to the enemy’s standard.”

The developing barbarity was graphically described in a letter of January 6 from O’Hara to the Duke of Grafton: “The violence and the passions of these people are beyond every curb of religion and humanity. They are unbounded, and every hour exhibits dreadful wanton mischiefs, murders, and violences of every kind, unheard of before. We find the country in great measure abandoned, and the few who venture to remain at home in hourly expectation of being murdered or stripped of all their property.” Needless to say, it was the revolutionary irregulars who were preponderantly the guilty party. Until King’s Mountain Major Patrick Ferguson, the Inspector of Militia, had used his best endeavors to suppress the irregularities of the Back Country loyalists, quite a few of whom had begun to plunder the opposing party. From King’s Mountain onwards the situation radically changed. Now, over much of the Back Country, there was an open door for the revolutionaries to do with the loyalists as they wished—and many did.

Towards the end of December the enemy in the Back Country received a welcome accession of strength when Col. Andrew Pickens broke his parole and went off with some 100 men from the Long Cane settlement. Assiduously courted until then by the British, he was a man of influence whose militia regiment, according to Allen, “was always esteemed the best in the rebel service.” He would soon take part in the Battle of Cowpens.

In the Ceded Lands above Augusta matters had taken a turn for the better by November. Of the inhabitants there, 255 loyalists had been formed into a militia under Thomas Waters, whereas there remained in the settlement 57 persons whose characters were unknown and 159 for whom 21 hostages had been carried to Savannah. Of the rest, 42 prisoners had been sent to Charlestown, 49 notorious and active revolutionaries were lying out, and 140 had gone off with Clark after his failed assault on Augusta in September.

Between Augusta and Savannah the developing situation was not so rosy. Nominally a revolutionary but more bent on plunder, a freebooter named James McKay[5] began to haunt the swamps along the Savannah River, capturing supplies bound for Augusta and eventually cutting the communication. In mid January Lt. Col. Thomas Brown, commanding at Augusta, detached Lt. John Camp and ten rangers to see that the militia provided proper escorts, but they were captured by McKay and all but one given a Georgia parole, that is to say, stripped, tortured, and put to death. Brown responded by detaching Capt. Alexander Wylly with 40 rangers to Matthews’ Bluff on the Savannah, but learning there that the whole of Beaufort District had revolted under William Harden to the tune of 500 men, Wylly prudently retreated. Fearing a general insurrection, Brown joined Wylly by forced marches with a further 40 rangers, about the same number of native Americans, and a body of royal militia. Encamped at Wiggan’s plantation some 30 miles from Black Swamp, he was attacked by Harden and McKay, who were routed, notwithstanding that all but ten of the royal militia fled or defected.

Brown hanged twelve men who had been involved in the torture and murder of Camp and his detachment, handed over to the native Americans another who had been traitorously complicit, and destroyed any settlement where he found plundered goods concealed. Harden would soon return to the fray, while McKay would continue to infest the Savannah.

In November Sir James Wright, the Governor of Georgia, pressed Cornwallis to equip and bear the expense of a troop of 50 horse which would otherwise be raised on the Georgia establishment. Its purpose would have been to patrol the vast territory between Savannah and Augusta, which—Brown’s excursion apart—was bereft of troops. Despite the risks, the request seems in retrospect to have been eminently reasonable, but in January Cornwallis turned it down on the grounds that cavalry was very expensive and useless if not well commanded. So, as Cornwallis began the winter campaign, Georgia was left with only 211 troops fit for duty at Savannah and the remains of 250 King’s Rangers at Augusta.

Across the northern border of South Carolina Major Gen. Horatio Gates, the Continental commander-in-chief in the south, had been keeping his men well out of harm’s way. By late November the Continentals, who had been reinforced with recruits from the north, numbered 1,450, of whom 400 had been formed into a light corps under Brig. Gen. Daniel Morgan. Gates had also been joined by Lt. Col. William Washington and 70 dragoons, besides having at his disposal 1,150 militia. He had advanced to Charlotte, to the south of which were posted Morgan, Washington and the militia, their front guarded by Lt. Col. William Richardson Davie and other irregular corps, who, according to Cornwallis, “have committed the most shocking cruelties and the most horrid murders on those suspected of being our friends that I ever heard of.”

The situation south of Virginia began markedly to change in favor of the revolutionaries after Major Gen. Nathanael Greene superseded Gates on December 4. Born in 1742 and a native of Rhode Island, Greene had been brought up a Quaker but was expelled from the Society of Friends in 1773 for attending a military parade. Commissioned a brigadier general in the Continental Army in June 1775, he served through the siege of Boston and in August 1776 was promoted to major general. He went on to play a prominent part in central operations, notably in the action at Trenton and the Battles of Brandywine, Germantown, and Monmouth. Having displayed a talent at Boston for not only gathering and conserving military supplies but also working tactfully amid intercolonial jealousies, he reluctantly became Quartermaster General in February 1778 and served till the beginning of August 1780. During this period his arrangements for supplying the army were a great improvement and much increased its mobility. Yet it is on his campaigns in the Carolinas that his reputation firmly stands. In them he would display patience, resolution, profound common sense, and a keen insight into Cornwallis’s mistakes, “qualities which go far towards making a great commander.” Admittedly he would never be victorious in battle, but in each case the strategic effect turned out decidedly to his advantage. Fortescue, who was singularly qualified to assess the merit of an officer, concluded, “Greene, who was a very noble character, seems to me to stand little if at all lower than Washington as a general in the field.” Greene would not long survive the war, dying on June 19, 1786 of sunstroke at his plantation in Georgia.

The troops found by Greene at Charlotte were in a wretched, disorderly state, almost bereft of provisions in an area that had been stripped clean. An immediate change of location was necessary. He therefore moved with the bulk of his troops to Hick’s Creek, nearly opposite to Cheraw Hill, on the Pee Dee. Arriving there on December 26, he established a “camp of repose” to refit and discipline his men, expecting to be provided with an abundance of provisions by the zealous revolutionaries in the neighborhood. As to the rest of his troops, he had come to a risky decision that was to have a profound effect on the war.

Conscious that his move to the south might dishearten the Back Country revolutionaries in South Carolina, Greene had detached Morgan to the area beyond Broad River under their control, the object being “to give protection to that part of the country and spirit up the people, to annoy the enemy in that quarter.” Morgan’s command comprised 320 Continental light infantry, 200 Virginia militia, and about 80 dragoons under William Washington. Quitting Charlotte on December 21, Morgan encamped four days later on the north bank of the Pacolet at Grindal’s Shoals, where he remained for much of the time till pressed by Tarleton. According to Graham, by January 17 Morgan had been joined by about 380 Georgia, North Carolina, and South Carolina militia, but if allowance is made for sickness and detachments, the total force he brought to the field on that momentous day did not exceed 850 men.

As evinced by the defeat of Major Patrick Ferguson, the war had shown that distant detachments beyond the reach of support were fraught with danger. In Morgan’s case, the risk would pay off.

Two or three days after Morgan had taken post on Pacolet a spy reported that Thomas Waters and some 250 Georgia loyalist militia had penetrated and were laying waste the habitations of revolutionaries on Fair Forest Creek. What occurred next is perhaps best summarised in Morgan’s own words: “On the 29th I dispatched Lt. Colonel Washington with his own regiment and two hundred militia horse, who had just joined me, to attack them. Before the colonel could overtake them, they had retreated upwards of twenty miles. He came up with them next day about 12 o’clock at Hammond’s Store House about 40 miles from our camp. They were alarmed and flew to their horses. Washington extended his mounted riflemen on the wings and charged them in front with his own regiment. They fled with the greatest precipitation without making any resistance. 150 were killed and wounded and about 40 taken prisoners. What makes this success more valuable, it was attained without the loss of a man.” Morgan omits to say that many of the unresisting loyalists were given no quarter, being quite simply butchered. This affair, the burning of Williams’ stockaded house, and the threat in general posed by Morgan set in motion the train of events that culminated in the disaster at the Cowpens. So much has been written about the battle there and the events leading up to it that it is unnecessary to elaborate, save to state the basic facts.

Reacting promptly to Morgan’s presence, Cornwallis ordered Tarleton on January 2 “to push him to the utmost.” Crossing to the west side of Broad River at Brierly’s Ferry, Tarleton proceeded to do so, advancing with the British Legion (451 rank and file), the 1st Battalion, 71st (249), the light company, 71st (69), the 7th (Royal Fusiliers) (167), and the 3rd company, 16th (attached to the guns, 41). In all, the rank and file numbered 977.[6] When allowance is made for officers, non-commissioned officers, and drummers, the total force came to some 1,150 men.[7]

On the 17th Tarleton came up with Morgan at the Cowpens and was comprehensively defeated in the ensuing battle. All his men were killed or captured apart from some 200 officers and men of the British Legion cavalry who fled. The day was lost due partly to the impetuosity of Tarleton but pre-eminently to the superlative generalship of Morgan, who, despite fewer numbers, inferior troops and unpromising terrain, disposed and led his men in a masterly way.

Cornwallis had by now commenced the winter campaign, having left Rawdon to command in the country from Georgetown to Augusta. Marching from Winnsborough on January 8, he received news of Cowpens on the 18th, the day on which he was joined by Leslie at Turkey Creek. “The late affair,” he confessed to Rawdon, “has almost broke my heart.” His situation was indeed critical, yet despite seeing infinite danger in proceeding, he saw certain ruin in retreating and was therefore determined to press ahead in pursuit of Morgan. Finding it impossible to take on wagons, he would soon burn all except those laden with rum, salt, spare ammunition, and hospital stores.

With the loss of so many of Tarleton’s detachment Cornwallis’s remaining troops fit and present for the winter campaign were the Brigade of Guards (690 rank and file), the 23rd (Royal Welch Fusiliers) (286), the 33rd (328), the 2nd Battalion, 71st (237), the Regiment of Bose (347), the Jägers (103), the Royal North Carolina Regiment (256), and the remains of the British Legion (174), making in all 2,421 rank and file. If we allow for officers, non-commissioned officers and drummers, the total for all ranks came to some 2,850 men.

Cowpens was a turning point in the war. It would lead, by an unbroken chain of consequences, not only to British defeat in the Carolinas and Georgia but also to the catastrophe at Yorktown.

Bibliography

Baskin, Margaret, “Charles O’Hara (1740?-1802)” and “Alexander Leslie (1731-1794)” (www.banastretarleton.org, June 30, 2005)

Boatner III, Mark Mayo, Encyclopedia of the American Revolution (D. McKay Co., 1966)

Cashin, Edward J., The King’s Ranger: Thomas Brown and the American Revolution on the Southern Frontier (Fordham University Press, 1999)

Fortescue, Sir John, A History of the British Army,vol III (Macmillan & Co. Ltd, 1902)

The Gentleman’s Magazine, lxxii (1802), 278

Graham, James, The Life of Daniel Morgan (New York, 1856)

Gregorie, Anne King, Thomas Sumter (The R L Bryan Co., 1931)

Higginbotham, Don, Daniel Morgan: Revolutionary Rifleman (University of North Carolina Press, 1961)

Kay, John, A series of Portraits and Caricature Etchings . . . With Biographical Sketches and Illustrative Anecdotes (Edinburgh, 1838)

Nelson, Paul David, General Horatio Gates(Louisiana State University Press, 1976)

Rankin, Hugh F, Francis Marion: The Swamp Fox (Thomas Y. Crowell Co., 1973)

Ian Saberton ed., The Cornwallis Papers: The Campaigns of 1780 and 1781 in the Southern Theatre of the American Revolutionary War, 6 vols (Uckfield: The Naval & Military Press Ltd, 2010) (referred to as “CP” in the footnotes to this article)

Tarleton, Banastre, A History of the Campaigns of 1780 and 1781 in the Southern Provinces of North America (London, 1787)

Ward, Christopher, The War of the Revolution (The Macmillan Co., New York, 1952)

Wickwire, Franklin and Mary, Cornwallis: The American Adventure (Houghton Mifflin Co., 1970)

Williams, Otho Holland, “A Narrative of the Campaign of 1780” in vol I of William Johnson, Sketches of the Life and Correspondence of Nathanael Greene (Charleston, 1822)

[1]Today’s Charleston, South Carolina.

[2]In January 1781 the troops under Rawdon’s command were set out in two returns appearing in The Cornwallis Papers: CP 3: 242-245 & 255-264.

[3]The Prince of Wales’s American Regiment.

[4]Wemyss: pronounced “Weems”.

[6]These and subsequent figures for rank and file are taken from those present fit for duty as stated in the return at CP 4: 61-2.

[7]The total for all ranks is extrapolated from the totals for rank and file by using a factor of 17.5%, being the consistent proportion of men other than rank and file in British and British American regiments.

2 Comments

Will the author kindly supply full references for all direct quotations.

Bruce

Thank you for your message. The answers, in relation to the pages of the article as printed, are:

P 5, para beginning “A principled man …”: Hugh F Rankin, “The Swamp Fox”;

P 7, para beginning “In a dispatch …”: Ian Saberton ed, “The Cornwallis Papers” (CP), 3: 173;

P7, para beginning “Garrisoning the village …”: CP 3: 176;

Pp 9-10, para beginning “Continuing to occupy …”: CP 3: 281;

P 10, para beginning “Immediately south …”: CP 3: 116;

Pp 11-12, para beginning “Besides the actions …”: CP 3: 273, 25, 28, 75;

P 12, para beginning “The developing barbarity …”: O’Hara’s correspondence with the Duke of Grafton was published in “The SC Historical Magazine” in 1942-3 if I recall correctly;

P 14, para beginning “Across the northern border …”: CP 3: 26;

Pp 14-15, para beginning “The situation south of Virginia …”: Sir John Fortescue, “A History of the British Army,” vol III;

P 15, para beginning “Conscious that his move …”: “The Papers of General Nathanael Greene, (University of NC Press), 6: 589;

P 16, para beginning “Two or three days after …”: James Graham, “The Life of Daniel Morgan”;

P 16, para beginning “Reacting promptly …”: Robert D Bass, “The Green Dragoon” (Henry Holt & Co, 1957), 143:

P 17, para beginning “Cornwallis had by now …:”: CP 3: 251.