When one thinks of the American Revolution, the places that most quickly come to mind are Lexington, Concord, Bunker Hill, Valley Forge, Yorktown. Yet during the War for Independence, Eastchester, New York, located only a few miles north of Manhattan, experienced with few exceptions calamitous depredations more constant and severe than any other area of the United States.

Pre-Revolutionary Eastchester

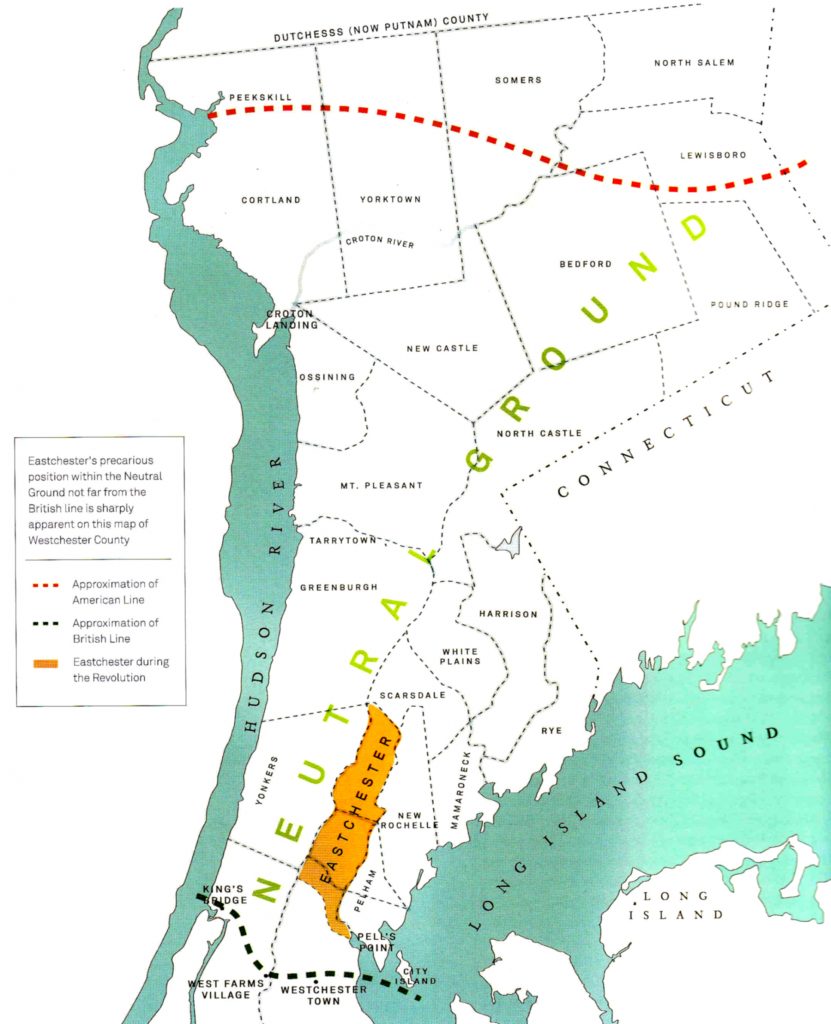

At the time of the American Revolution, Eastchester’s borders were the Bronx River on the west, New Rochelle and Pelham on the east, Scarsdale on the north, and what is today the northeast Bronx on the south.[1] The Bronx did not exist as a borough of New York City; it was part of Westchester County. In fact, Westchester County at the beginning of the Revolution covered all the territory north of the Harlem and East rivers, which formed its southern boundary, to what is now Putnam County to the north. The county was bordered by the Hudson River on the west and Long Island Sound on the east.

Eastchester, in the southernmost part of Westchester County, as well as the rest of the county, was largely a farm-based economy.[2] The terrain was especially suited for grazing, so that many farmers engaged in livestock and dairy husbandry, while the rich soil and temperate climate allowed others to raise abundant produce. About two-thirds of the county was manor land where tenant farmers enjoyed long leases at moderate rates. Farmers had ready and ever-growing markets in not-too-distant New York City for meat, dairy products, and vegetables.

Westchester County consisted of a few villages with a small number of inhabitants and farms scattered over large tracts of land. Other than gristmills and sawmills, there was no manufacturing.[3] There were few merchants and services, and those individuals—blacksmiths, masons and carpenters, tailors and shoemakers, and storekeepers and tavern owners—mainly supplied the needs of the local farmers and usually farmed on a small scale as well. Eastchester, along with the rest of the county, was affluent and there was little crime.

Most pre-Revolution residents of Eastchester were apolitical and remained indifferent to early rumblings of discontent from the Sons of Liberty and other more rebellious factions in New England.[4] The early controversies between Great Britain and America, which began in 1763, did not especially affect the farmers in Westchester as they did merchants in more urban areas. Residents of the county had worked hard to achieve their life of comfort, and they resisted any change that a war would represent. Isaac Wilkins, a prominent Westchester resident, implored the New York Assembly in 1775, “The necessity of a speedy reconciliation between us and our mother country must be obvious to everyone who is not totally destitute of sense and feeling.”[5]

Reluctant Farmers Take Sides

Westchester was finally pushed over the edge into full-fledged involvement in the war by the convergence of the American and British military forcesin the county in the fall of 1776. Strategists from both countries had calculated that the Hudson River Valley was key to control of communications between the New England and southern colonies. They further determined that the region, especially Westchester County and Long Island, with abundant supplies of livestock and foodstuffs, was essential to adequately feed their armies. George Washington reinforced this point the following year in a letter to Maj. Gen. Israel Putnam when he urged him to use his whole force and every effort to defend the river, “The importance of the North [i.e., Hudson] River in the present contest and the necessity of defending it . . . are so well understood that it is unnecessary to enlarge upon them.”[6] Accordingly, in July 1776, the British began a campaign to control Staten Island, Long Island, New York City, Westchester County, and New Jersey, and Gen. George Washington strategically deployed his army and state militias to prevent the British from achieving their objective of a quick end to the war.[7] With these actions, the die was cast, thus commencing seven years of constant terror from which the inhabitants of Eastchester and the rest of the county emerged changed. In the midst of all this turmoil and despite the hopes of most Eastchester and Westchester County farmers to avoid war, the Continental Congress in Philadelphia adopted the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, thus severing ties with Great Britain forever.

The War Begins in Earnest in Westchester

General Washington had arrived in New York on April 13, 1776, to find a poorly equipped army of 10,235 men of which only about 8,000 were fit for duty.[8] British Gen. William Howe’s force accumulated on Staten Island over the summer, numbered by August, 31,600 fully armed and equipped men. The British began their attempt to capture New York that month and soon took control of western Long Island, and by September 16, they were in control of New York City.

Washington spread the bulk of his troops over the northern end of Manhattan. Howe’s strategy was to land a British force of 4,000 men in today’s southeast Bronx, a narrow peninsula that separates the passage between the East River and Long Island Sound and projects about two miles into the sound. His goal was to have his troops establish a line across what is now the Bronx to the Hudson River, thereby encircling the Continental forces and preventing their escape from Harlem Heights.[9] American Gen. William Heath and Col. Edward Hand posted twenty to twenty-five riflemen on the westerly side of the causeway from Throgg’s Neck across the Hutchinson River to the Westchester mainland with orders to protect the causeway and, if necessary, to take up the planks of the bridge over it.[10] On October 12, 1776, when British troops began their march along the causeway, the Americans ripped up the bridge planks and as the British troops approached fired on them with great accuracy. This unexpected attack confused the British who immediately retreated. Washington praised the bravery of this small group of riflemen: “A brave and gallant behavior for a few days, and patience under some little hardships, may save our country and enable us to go into winter quarters with safety and honor.”[11] Howe apparently decided rather than pursue the American troops at this point, to engage them at Pell’s Point, about three miles north of Throgg’s Neck. Thus, six days after Howe’s retreat, the scene was set for the first full-scale battle in Westchester.

Pell’s Point—The Battle That Prevented America’s Defeat

The landing of such a large British force at Throgg’s Neck had convinced Washington of the need to evacuate Manhattan Island. Learning from British army deserters that Howe next planned to land on Pell’s Point, Washington placed a small force under the command of Col. John Glover in the area, after which he began the laborious exit from Manhattan through the hills west of the Bronx River.[12] The Americans were just beginning to leave Kingsbridge on October 18, 1776, when Howe landed 4,000 British and Hessian troops on Pell’s Point in today’s Pelham Bay Park.[13]

On the morning of October 18, Colonel Glover through his spyglass clearly saw British troops landing. Taking a force of about 750 men, he divided them into small units and positioned them at staggered intervals behind stone walls along Split Rock Road, the route the British would take.[14] The first of these units waited until the enemy came within thirty yards, rose from behind their wall and fired, and then retreated to the next cover. This stunned the Redcoats who withdrew in confusion before returning an hour and a half later. Again, when the enemy came within close range, the Americans rose and opened fire, then retreated. After the third unit repeated this tactic and the American position became difficult to defend, Glover’s troops pulled back. Against overwhelming odds, this small force of brave Americans had held off the enemy long enough for Washington to escape to White Plains. Three days later Washington expressed his appreciation to Glover and his men: “The hurried situation of the General for the last two days, having prevented him from paying that attention to Col. Glover, and the officers and soldiers who were with him this Friday last, that their merit and good behavior deserved—He flatters himself that his thanks, tho delayed, will nevertheless be acceptable to them, as they are offered with great sincerity and cordiality.”[15]

With the American loss at White Plains on October 28, the British retreated to lower Westchester and Manhattan, while American forces moved further north to North Castle and Peekskill. There were no other major battles in Westchester after White Plains, but the county was caught between opposing armies and, as a result, Eastchester residents, along with the rest of Westchester County, suffered mightily during the remainder of the war.

The Neutral Ground—Eastchester’s Quagmire

During the American Revolution probably the most crime-ridden and violent area in the thirteen colonies was a section of Westchester County known as the Neutral Ground, the area held hostage between the lines of the opposing armies—with American forces to its north and British forces to its south. Most authorities assert that Kingsbridge in the Bronx (then part of Westchester County), just across the Harlem River from Manhattan, marked the southern boundary and Peekskill the northern boundary of the Neutral Ground.[16]

Eastchester’s location very near the southern boundary put it closest to the largest camp of British troops in the New York colony. For most of the war, the Neutral Ground was subject not only to occasional skirmishes between American and British troops but also, and much worse, to frequent and devastating raids of the farmland by local militias, the “Skinners,” who rode for the Americans, and the “Cowboys,” who rode for the British. Probably the most reprehensible action recorded during this period was the willful participation of some American troops in the plunder of American families in the Neutral Ground.[17]

In 1777, after the main military conflict shifted to New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and other more northern parts of New York, British troops in the lower Hudson Valley focused on obtaining the livestock, lumber, sugar, wheat, flour, and other materials they needed for their headquarters and outpost camps from nearby Westchester County. They also set about punishing Whig leaders. While their troops participated in all these activities, the Cowboys,composed mainly of rough local farmhands (as were the Skinners), carried out the bulk of the atrocities inflicted on the inhabitants of the Neutral Ground.

A first-hand account vividly illustrates the suffering of one Eastchester family at the hands of these ruffians. As an adult, Timothy Hunt of Eastchester recounted that when he was only nine years old his family was “left between the lines, in a most equivocal and unpleasant situation.” The unpleasant situation included an incident around 1777 when British troops encamped in his family’s orchard. A British light-horseman bargained for one of his family’s pigs, telling Timothy to come with him to camp, where he would give him money for the pig. The boy did so, but when about half way there, the officer “drew his sword, and said, ‘Run you little _____, or I will cut off your head.’”[18]

When Timothy was fourteen another “tragical scene occurred after the declaration of peace,” which would have made it sometime after early 1783. Tory refugees, desperate at their last chance to rob local residents, seized Timothy while he was driving cows home. When they reached the farm, they bound his stepfather and demanded one thousand dollars of him. When his stepfather was either unable or unwilling to pay, they proceeded to torture him by applying a red-hot shovel to his naked flesh.[19]

In between these two incidents, his family experienced frequent raids and threats by both Cowboys and Skinners, which demonstrates that the cruelty inflicted on people in the Neutral Ground occurred over many years. The Hunt family’s experiences were not the exception, but were very common during this period. Although the Skinners in theory were supposed to be on the American side and the Cowboys on the British, both indiscriminately and frequently pillaged and destroyed property of the unfortunate farmers residing between the two armies. Washington Irving put it succinctly, “Neither of them stopped to ask the politics of horse or cow, which they drove into captivity, nor when they wrung the neck of a rooster did they trouble their heads to ascertain whether he had crowed for Congress or King George.”[20]

Soldiers Add to County’s Woes

In addition to the Cowboys and Skinners, British regular troops frequently scoured the Neutral Ground both in occasional skirmishes and on excursions to take livestock and grain or to destroy anything they could not use to prevent its use by American soldiers. British Col. Stephen Kemble, an aid to General Howe, admitted in his journal, “The Country all this time [was] unmercifully Pillaged by our Troops, Hessians in particular. No wonder if the Country People refuse to join us.”[21]

The American army also participated in these crimes. Commissioned officers and privates alike entered farmsteads, caring little whether they were owned by Whigs or Tories, and took whatever they wished. Washington, on hearing reports of these acts, was outraged and ordered that they be stopped: “It is with astonishment the General hears that some Officers have taken horses, between the enemy’s camp and ours, and sent them into the country for their private use. . . . He hopes every officer will set his face against it, in future; and does insist that the colonels and commanding officers of regiments immediately inquire into the matter and report to him who have been guilty of these practices.”[22]

Even though Washington publicly deplored the plundering of county residents by his army, he aggravated the distress of this same population by military impressments of inhabitants’ livestock and grain in return for certificates, which often proved worthless or of diminished value after the war.[23] Determined that the British obtain as little livestock and other provisions as possible from farms in the Neutral Ground, he ordered his military to take everything other than what was absolutely required by these families for survival.

Families Divided

As horrific as the constant fear for home and limb experienced by those living in the Neutral Ground was, the divided allegiances among neighbors and even family members also had heart-rending consequences. When the British settled in at the northernmost edge of Manhattan and the Americans retreated to the hills of northern Westchester, a battle of a different sort took place to win the hearts and minds of those residing between the lines. With Eastchester so close to the British line, it was especially susceptible to frequent encouragement by the British to join the Tory cause. Two prominent Eastchester families torn asunder by the war were the Fowlers and the Wards.

Jonathan Fowler, one of Eastchester’s most eminent citizens at the time, was a judge in Westchester County. He vehemently opposed the Patriots, which led to his arrest, with others, in Sear’s Raid of November 1775.[24] He must have been outraged when his son, Theodosius Fowler, joined the American army in March 1776 and recruited openly for more soldiers to enlist. The younger Fowler fought on the American side in the battles of Long Island, Saratoga, Monmouth, and Yorktown, rising to the rank of captain.[25] Jonathan Fowler died in 1787, his son Theodosius in 1841. Both are buried in the Fowler family plot at St. Paul’s Church in Mount Vernon, New York.[26]

The Ward family, an influential Eastchester family dating back to the late seventeenth century, had sorely divided loyalties. Two brothers, both of considerable economic and social stature prior to the war, cast their lots with opposing sides—Stephen with the Americans, Edmund with the British—thereby severing their ties for years to come.

Prior to the Revolution, Stephen Ward, an extremely dedicated Patriot, was a town assessor and, at the time of the Revolution, town supervisor. In May 1775 he was appointed to the first Provincial Congress and in 1776 to the Committee to Detect Conspiracies.

Town records show that before the Revolution Edmund Ward, one of Eastchester’s wealthiest landowners, was “Overseer of ye Roads” and a “viewer of fence and damiges.”[27] During the war, he remained inflexibly loyal to the British Crown and advocated resolving the conflicts provoked by British taxes and other restrictions with less aggressive measures than all-out war. In 1776, Ward was imprisoned in White Plains for his views. Stephen, as a member of the Committee to Detect Conspiracies, would have had a hand in the imprisonment of his brother. Edmund Ward escaped in March 1777 and fled to New York City, where he remained under British protection for the rest of the war.[28]

Edmund’s wife Phebe and their six sons[29] remained in Eastchester and worked their farm under the most difficult conditions through seven long years of war. Residing in the Neutral Ground, not only was she in danger from the Cowboys and Skinners and armies of both sides, but she probably also suffered the censure of many neighbors for what they considered the traitorous behavior of her husband.

Two years before the war ended, on November 10, 1780, Edmund Ward was indicted under the Confiscation Act, which resulted in his loss of 252 1/2 acres of land as well as two houses and lots in New York City.[30]

In 1783, Edmund, Phebe, and their children, along with many other Loyalists, sailed for Nova Scotia where they lived under British protection for about a decade.[31] On August 11, 1789, Phebe Ward petitioned New York governor George Clinton and the general assembly asking for relief from the continual hardship the loss of their property caused her family. This petition, now in the Library of Congress, was found in the papers of Alexander Hamilton in a wrapper marked “petition from Phebe Ward,” in Hamilton’s handwriting.[32] As far as is known, the petition was denied. There had to have been a reconciliation with Stephen Ward, for Edmund and Phebe Ward returned to Eastchester in the 1790s; they are buried along with Stephen Ward in the cemetery at St. Paul’s Church.

Post-Revolutionary Eastchester—A Changed People

For seven dreadful years of war, the people of Eastchester suffered. They, along with the residents of the rest of the county, were at the mercy of forces on all sides—British and American armies, Cowboys, Skinners and other renegades—from 1776 through 1782. After the war, farmers often had to mortgage their homes to pay the cost of replacing livestock, equipment, barns, fences, and other materials either taken from them or destroyed. When they could not repay these loans, which was often the case, they frequently lost their farms and faced years of poverty.[33]

As significant as were the economic and physical hardships suffered, the psychological toll of living in daily fear for their lives and homes for such a protracted period severely damaged the spirit of these once contented people. By 1782, the population was riddled with suspicion and despair.Timothy Dwight, a chaplain in the Continental army, recalled his observations of the war’s impact on Westchester inhabitants: “They feared everybody who they saw and loved nobody. . . . To every question they gave such an answer as would please the inquirer; or, if they despaired of pleasing, such a one as would not provoke him. Fear apparently was the only passion by which they were animated.”[34]

There is little statistical data to gauge the impact of the war on population growth or decline in Eastchester. It appears, however, that the population of Westchester County declined during the war years. Eastchester, so close to the British line, is likely to have experienced a decrease in population as well. Pre-History to 1783: Colonial Westchester and the Revolution reports that Westchester was the richest and most populous county in the colony of New York in 1775 and, conversely, “in 1783, after seven years of suffering, Westchester’s countryside was devastated and its population depleted.”[35]

Although limited, there is some statistical evidence of a population decline in the county. According to colonial enumerations in the decades before the Revolution and federal censuses after the war, the population of Westchester County in 1756 was 13,257; in 1771, 21,745; and in 1786, 20,554.[36] These numbers indicate that in just fifteen years, from 1756 to 1771, the population grew by 8,488 (or 64 percent), while in the fifteen years between 1771 and 1786, which included the prosperous pre-war years of 1771 through 1774 as well as the war years, the population actually declined by 1,191 persons (or -5.5 percent). This strongly suggests that the county experienced a decline in population during the war and the years that immediately followed. Shonnard and Spooner in their History of Westchester County concluded “the decline (in population) during the Revolution must have been considerable.”[37]

The federal censuses extend only as far back as 1790. At that time, seven years after the war ended, Eastchester’s population stood at 740 residents, in 1800 at 738, and in 1810 at 1,039.[38] Even though there are no pre-Revolution numbers for Eastchester alone, it is reasonable to infer that Eastchester’s population closely tracked the county’s. The flat growth rate from 1790 to 1800 suggests that Eastchester was still suffering from the war’s impact a decade and a half later, whereas the county as a whole had grown by more than fourteen percent during that same ten-year period (from 23,941 in 1790 to 27,423 in 1800). This comparison reinforces the supposition that Eastchester’s proximity to the British forces at Kingsbridge contributed greatly to the severity of its situation. From 1800 to 1810, however, there was a 41 percent growth in population in Eastchester, indicating the town was on the road to recovery.

Literary and anecdotal evidence also suggest that Eastchester suffered a decline in population during the war. Many British sympathizers left Eastchester during and right after the war because of Patriot animosity toward them. Many never returned. In addition, not only Loyalists, but some Patriots left Eastchester during the war. Even so committed a Patriot as Stephen Ward fled to Fishkill with his wife and children in August or September 1776 and did not return until 1783.[39] Dr. James Thacher, a surgeon in the Continental army, seemed to corroborate this point in his description of Westchester County in 1780: “The country is rich and fertile . . . but it now has the marks of a country in ruins. A large proportion of the proprietors having abandoned their farms, the few that remain find it impossible to harvest their produce.”[40]

From 1776 on, the debilitating effects of the war, physical, economic, political, and emotional, impacted the people in the Neutral Ground for many years to come. Eastchester shared this fate with the rest of those unfortunate enough to have resided between the British and American forces during the war. Peace, however, brought a gradual return to prosperity, putting Eastchester on the road to recovery as the population grew and communities rebuilt their homes, religious and political institutions and livelihoods.

[1]Map of Township of Eastchester containing 6,919 acres, surveyed and drawn by Christopher Coles, 1797, Westchester County Historical Society.

[2]Otto Hufeland, Westchester County During the American Revolution, 1775-1783 (Harrison, NY: Harbor Hill Books, 1982), 10.

[3]Alvah P. French, History of Westchester County New York (New York: Lewis Historical Publishing Company, Inc., 1905), 83.

[4]Sung Bok Kim, “The Limits of Politicization in the American Revolution: The Experience of Westchester County, New York,” The Journal of American History, 80, no. 3 (December 1993): 871.

[5]Isaac Wilkins, “Address to the New York Assembly, Debates, 23 February 1775,” 1, American Archives, at 1295.

[6]”George Washington to Maj. Gen. Israel Putnam, December 2, 1777,” in George Washington Papers, Series 3, Varick Transcripts, 1775-1785, Subseries 3B, Continental and State Military Personnel, 1775-1783, Letterbook 4: Aug. 1, 1775-Jan. 20, 1778, Library of Congress, 318.

[8]Hufeland, Westchester County, 100.

[9]Lloyd Ultan, The Northern Borough: A History of the Bronx (Bronx, NY: The Bronx County Historical Society, 2005, 2009), 91.

[10]Hufeland, Westchester County, 110.

[11]”General Orders, Head Quarters, Harlem Heights, October 13, 1776,” in George Washington Papers, Series 3, Varick Transcripts, 1775-1785, Subseries 3G, General Orders, 1775-1783, Letterbook 2: Oct. 1, 1776-Dec. 31, 1777, Library of Congress,18.

[12]Ultan, Northern Borough, 91.

[13]Hufeland, Westchester County, 115.

[15]”General Orders, Head Quarters, Harlem Heights, October 21, 1776,” in George Washington Papers, Series 3, Varick Transcripts, 1775-1785, Subseries 3G, General Orders, 1775-1783, Letterbook 2: Oct. 1, 1776-Dec. 31, 1777, Library of Congress, 24.

[16]Kim, “Limits,”880; Hufeland, Westchester County, 236; Richard Borkow, George Washington’s Westchester Gamble: The Encampment on the Hudson & the Trapping of Cornwallis (Charleston: The History Press, 2011),19; Frederic Shonnard and W. W. Spooner, History of Westchester County New York: From Its Earliest Settlement to the Year 1900 (New York: The New York Historical Society, 1900; reprinted Harrison, NY: Harbor Hill Books, 1974), 418.

[17]French, Westchester, 116-18.

[18]Timothy Hunt, “Personal Reminiscences of the Revolutionary War,” The National Magazine, ed. Abel Stevens, no. 2 (January to June 1853): 129.

[20]Washington Irving, “Wolfert’s Roost and Miscellanies: A Chronicle of Wolfert’s Roost,” The Works of Washington Irving, Fulton Edition (New York: The Century Company, 1909). Evidence that Irving wrote this quote in 1839 or 1840 is provided on page 22 of “Wolfert’s Roost and Miscellanies,” where Irving says that Jacob Van Tassel, a long-time owner of Wolfert’s Roost (later named Sunnyside), was in his ninety-fifth year. Van Tassel died on August 24, 1840, at the age of ninety-six.

[21]Stephen Kemble, “Journals of Lieut.-Col. Stephen Kemble, 1773-1789; and British Army Orders: Gen. Sir William Howe, 1975-1778; Gen. Sir Henry Clinton, 1778; and Gen. Daniel Jones, 1778,” in Collections (New York: New York Historical Society, 1883), 96.

[22]“General Orders, Head Quarters, Harlem Heights, October 31, 1776,” in George Washington Papers, Series 3, Varick Transcripts, 1775-1785, Subseries 3G, General Orders, 1775-1783, Letterbook 2: Oct. 1, 1776-Dec. 31, 1777, Library of Congress, 33.

[24]French, Westchester, 101-02.

[25]David Osborn, “Theodosius Fowler, Revolutionary War Soldier,” National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, July 2007, www.nps.gov/sapa/learn/historyculture/upload/Theodosiusfowlerforwebsite.pdf. According to Hufeland, Westchester County, 87, three of Jonathan Fowler’s sons, Jesse, Joseph, and Theodosius, joined the American Army.

[26]At the time of the Revolution, Mount Vernon was part of Eastchester. It incorporated as a city on March 22, 1892. St. Paul’s Church in Mount Vernon was begun in 1763. Construction was halted during the war, at which time it served as a hospital, first for the Americans and, after the Battle of Pell’s Point, for the British. It was completed in 1788. The exterior of St. Paul’s Church appears today much as it did at the time of the Revolution. It and its adjacent cemetery, where Stephen, Phebe and Edmund Ward and members of the Fowler family are buried, are open to the public.

[27]John V. Hinshaw, “The Wards of Eastchester,” The Westchester Historian, 52, no. 3 (Summer 1976): 53.

[28]Robert Bolton, The History of Several Towns, Manors, and Patents of the County of Westchester, from Its First Settlement to the Present Time, ed. C. W. Bolton (New York: Chas. F. Roper, 1881), 1:256.

[30]Julius Goebel, Jr., ed. The Law Practice of Alexander Hamilton: Documents & Commentary (New York: Columbia University Press, 1964), 1:261. On the indictment, see also copy of letter from Matthew Visscher to Hamilton, August 11, 1789, Hamilton Papers, Library of Congress.

[31]David Osborn, “The Ward Family and the American Revolution,” National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, n.d.

[32]“Petition from Phebe Ward,” August 11, 1789, Hamilton Papers, Library of Congress.

[33]Ultan, Northern Borough, 104.

[34]Timothy Dwight, S.T.D., “State of Westchester in 1777,” Travels in New England and New York (London: Charles Wood, 1823), 3:471.

[35]“Pre-History to 1783: Colonial Westchester and the Revolution,” www.westchestergov.com/history/1783.htm.

[36]Provincial censuses (1756-1786), Franklin B. Hough, Census of the State of New-York for 1855 (Albany: Charles Van Benthuysen, 1857), vi-viii.

[37]Shonnard and Spooner, Westchester, 418. The authors relied on a slightly higher 1790 census number (24,003) that resulted from a mathematical error and subsequently has been corrected.

[38]Federal Censuses, United States 1st, 2nd, 3rd Censuses, 1790, 1800, 1810.

[40]James Thacher, A Military Journal During the American Revolutionary War, From 1775 to 1783 (Boston: Cottons & Barnard, 1827), 232.

5 Comments

This is a fascinating piece on an obscure part of the civil conflict which plagued various parts of the colonies during the Revolutionary War. The Neutral Ground was torn asunder and took a long while to recover after the war was over. A very enjoyable read!

This is an interesting addition that expands upon the area’s history. I have been to the reenactment of the battle of Pell’s Point and nighttime graveyard walk held annually at Saint Paul’s church several times. NPS site manager David Osborne is a wealth of information and the event is worth attending.

Jim,

Thanks for your comment. I completely agree with your assessment of David Osborn’s encyclopedic knowledge of the Revolutionary period. I’ve attended many lectures at St. Paul’s Church as well as the tour of the Pell’s Point battleground. An especially wonderful event at St Paul’s happens on July 4 each year. In addition to David giving one of his interesting off-the-cuffs talks, the Declaration of Independence is read by a member of the same family who has been doing this for over 100 years. While he reads, the tower bell, which was buried for safety reasons during the Revolution, is rung 13 times to represent the 13 colonies. It’s very moving and well worth a visit if you or other Journal readers are in the area.

Hello Edna,

You have written a excellent story of the neutral zone in New York. I personally like to hear about local revolutionary history.

There was also a “neutral zone” in Pennsylvania after the British took Philadelphia. I am sure there are similar stories to be shared in that area.

Keep producing stories like this, I love them.

Denny Ness

I’m always fascinated by the effects the war had on everyday life for so many people. Wonderful job getting into the harsh realities of living in the neutral ground!