George Washington understood the importance of naval power. He recognized the futility of trying to defend New York City, surrounded as it was by water that the British Navy could use to maneuver around his flanks. “The amazing advantage the Enemy derive from their Ships and command of the Water keeps us in a State of constant perplexity.”[1]

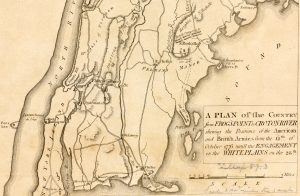

British General William Howe used the ships of his brother Richard Howe’s fleet to move their troops to Staten Island and then on to Long Island, resulting in a flanking maneuver that forced the evacuation of the island. Howe used the fleet again to land at Kip’s Bay northeast of New York City, easily dispersing the Connecticut militia assigned to protect that area and forcing Washington to evacuate the city. A few days later, the British made another landing on the American’s northeastern flank on the peninsula at Throg’s Point. Washington brought part of his army into a position to stall the British move but also began moving the remainder of his forces from the island of Manhattan. The British fleet sat at anchor off the shore. Would they outflank him again?

Washington placed part of the army on the West Chester Heights overlooking the British on Throg’s Point, and rushed the main body over King’s Bridge to leave Manhattan Island. Col. John Glover and his brigade were posted to the north at East Chester. Forty-three year old Glover was a successful businessman who used the seafaring trades to make his living in Marblehead, Massachusetts. On the morning of October 18, 1776, from the heights that his position afforded him, Glover saw a small fleet of British ships landing large numbers of soldiers at Pell’s Point a couple of miles northeast of Throg’s Point. Using the cover of darkness, Gen. William Howe had made his move.

First, Howe made a diversionary move to the west toward Morrisiana but Glover was unaware of that; all he knew was that the British were landing at Pell’s Point in front of him. He sent one of his staff officers, William Lee, to inform his division commander, Maj. Gen. Charles Lee, and also to ask for orders. Keeping his eye on the British, Glover spotted their advance guard of thirty men. He quickly ordered a group of about forty men to reconnoiter and possibly delay the enemy. He knew it would be some time before General Lee could send instructions, so he acted on his own. “I did the best I could, and I disposed of my little party to the best of my judgment.”[2]

Glover’s brigade was composed of four regiments and three cannon. One of the regiments was Glover’s own, the so-called “Marbleheaders.” It was designated the 14th Continental Regiment. Consisting of 179 men, they had already attained fame for their part in helping evacuate Washington’s army from Long Island. His second regiment, the 3rd Continental Regiment, was composed of 204 men and commanded by French and Indian War veteran William Shephard. Joseph Read of Uxbridge, Massachusetts, commanded the 13th Continental Regiment mustering about 226 men. The last regiment in the brigade, the 26th Continental, was led by Loammi Baldwin, of Woburn, Massachusetts and contained about 234 men.[3]Baldwin had been sick in bed but roused himself just in time to join the regiment as it moved forward.

Sizing up the situation, Glover placed Read to the left of the approach road behind a wall out of sight of the British. He placed the regiments of Shephard and Baldwin in echelon to the right rear of Read, also under cover of stone walls. Glover’s own regiment was placed in reserve with the three pieces of artillery. Glover took up a position with Read’s men but doubted his dispositions in the face of the enemy: “I would have given a thousand worlds to have had General Lee, or some other experienced officer present to direct, or at least approve of what I had done.”[4]

The British force numbered about 4,000: three blue clad Hessian regiments with red clad British grenadiers, light infantry, and dismounted dragoons. Glover had no more than 750, with only about 625 immediately facing the enemy. Glover accompanied the first group of forty Americans who gave the British advance guard a blast of fire and then hustled back toward their main body, as did the British advance party. Halted briefly by the short engagement, it took over an hour for the British to organize themselves and advance down the road.

Read’s men waited until the British were within one hundred feet and opened fire. The Continentals, many of whom had never been under fire before, quickly reloaded. They fired again and again as the surprised British light infantry and German jägers advanced. After seven rounds, Glover ordered Read’s outnumbered men to retreat. The British pushed on but found themselves confronted by more Americans.

Atop the slight rise called Prospect Hill, Shephard’s men were positioned behind a double stone wall. Blasted by this new line of Americans, the British halted and began a firefight that involved infantrymen’s muskets and seven cannon. The Americans held on for nearly an hour, firing about seventeen rounds apiece, before the enemy fire drove them from their position. Shephard was wounded in the neck.

British troops moved to outflank the Continentals as they found more room to maneuver. Baldwin’s regiment fired only one volley before it was ordered to retreat with the other two regiments and join Glover’s own regiment across the Hutchinson River. The British refused to follow any further and satisfied themselves with an artillery duel that lasted until dark.

Glover’s small battle, in which neither side lost more than thirty or forty men, allowed Washington to extract his men from Throg’s Neck and Manhattan Island. They took up positions near White Plains. Glover’s brigade rejoined the main army and participated in the rest of the New York campaign. The division commander sent his congratulations to Glover’s men:

General Lee returns his warmest thanks to Colonel Glover and the brigade under his command, not only for their gallant behavior yesterday, but for their prudent, cool, orderly and soldierlike conduct in all respects. He assures these brave men that he shall omit no opportunity of showing his gratitude.[5]

General Washington included his approbation in the General Orders on October 21, 1776:

The hurried situation of the Gen. the last two days having prevented him from paying the attention to Colonel Glover and the officers and soldiers who were with him in the skirmish on Friday last that their merit and good behavior deserved, he flatters himself that his thanks, though delayed will nevertheless be acceptable to them.[6]

Glover’s men retreated with the army from New York and through New Jersey. They performed yeoman service in transporting Washington’s army across the Delaware River on Christmas night, 1776. Although Washington lamented British mobility using their fleet, Glover’s men had provided a maritime force that provided the Continental Army with a similar mobility on water.

Washington valued Glover’s service. He was disappointed when Glover left the army at the beginning of 1777 and refused to accept a promotion to brigadier general. The commander in chief wrote him:

Sir,

After the conversations, I had with you, before you left the army, last Winter, I was not a little surprised … As I had not the least doubt, but you would accept of the commission of Brigadier, if conferred on you by Congress, I put your name down in the list of those, whom I thought proper for the command, and whom I wished to see preferred.

Diffidence in an officer is a good mark, because he will always endeavour to bring himself up to what he conceives to be the full line of his duty; but I think … without flattery, that I know of no man better qualified than you to conduct a Brigade, You have activity and industry, and as you very well know the duty of a colonel, you know how to exact that duty from others.[7]

Glover accepted the promotion and returned to the army, serving until the end of the war.

[1]George Washington to John Hancock, July 25, 1775, in Frank E. Grizzard, ed.,The Papers of George Washington, Vol. 10, 11 June 1777-18 August 1777(Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia, 2000), 410.

[2]William P. Upham, Memoir of General John Glover, of Marblehead(Salem, MA: Charles W. Swasey, 1863), 18.

[3]Nathan P. Sanborn, Gen. John Glover and his Marblehead Regiment in the Revolutionary War: a paper read before the Marblehead Historical Society, May 14, 1903(Marblehead, MA: Marblehead Historical Society, 1903), 25.

[5]General Orders, October 19, 1776, in Ibid., 28.

[7]Washington to John Glover, April 26, 1777, in Philander D. Chase, ed.,The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 9, 28 March 1777-10 June 1777(Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia), 274.

7 Comments

“The British force numbered about 4,000: three blue clad Hessian regiments with red clad British grenadiers, light infantry, and dismounted dragoons.”

Unfortunately, this (considerable) over-estimate of the Crown forces is entirely due to early 20th Century American historians getting a little too “enthusiastic” about the battle and mis-understanding the basic organisation of British/Hessian units, counting each individual company of a grenadier unit as indicating the entire parent regiment was present (including one – the Garde – that never left Germany!). Numbers engaged were almost identical, with a 400-strong British Light Battalion (the 1st under Musgrave, later of Chew House fame) supported by two 3-pdr guns, about 100 jaeger, and the von Linsing grenadier battalion (companies of the 2nd and 3rd battalions of the Garde and one each from the regiments Leib and von Mirbach – 400-450 men), Musgrave deploying to the east of the road and Linsing to the west, respectively. To Musgrave’s right, a flanking force of another Hessian and one, possibly two British, grenadier battalions – just over 1,000 men – plus some guns, took a circuitous route heading north, and only arrived opposite Glover’s camp at the end of the day. This outflanking move could be clearly seen by Glover (and his retreat timed accordingly), but his principal position itself was secure, being flanked on the right by a combination of the tidal waters of Pelham Bay/Long Island Sound, water meadows and farmland covered in orchards; and on the left by a steep-sided (and probably also heavily wooded) ravine that required a long detour to circumvent. Glover also had at his disposal about 120+ Connecticut militia, who guarded the area to the west of the road, giving him around 900 men in total against about 1,000 British and Hessians able to assault him directly.

Estimates of British casualties are also wildly over-stated (unsurprisingly, as they came primarily from deserters), but also because the British light infantry had developed a tactic of “going to ground” on observing enemy troops about to fire.

The bulk of this information was obtained, either directly from, or via avenues of research suggested by, Lt Col Frank Licomelli (US Army), a former West Point lecturer.

Could you provide me with contact info for Lt Col Frank Licomelli? I would like to see his source information for this claim. It sounds valid, but I need an archival or published source.

Thanks for the information.I assume those historians thought it makes a better story with 750 against 4,000! I did not include any estimates of British casualties for the reason you stated, they all seemed highly inflated.

Few Revolutionary generals deserve new biographical treatment more than John Glover. His orderly book survives (with a couple missing pages) in the Library of Congress, a national treasure if there ever was one. Thanks to Jeff for this article and to Brendan for his clarifications. I look forward to reading more about Glover.

We watched “The Crossing” the other night. I had never heard of Glover before. Another hero whose song deserves some singing.

Go to Saint Paul’s Cemetery in Mt Vernon, NY; on the left side way in the back is a mass grave of Hessians.

As well we live in Pelham Manor. Our house on Peace street is on top of Prospect hill. A neighbor found a cannanball in there back yard when an addation Was being installed. The look out point up the now Hutchison river then Eastchester river was and still is split rock off the exit from the hutch to 95 top of the hill, walk my Boy Scouts there every year. If you follow the old paths and wolfs lane where we got the brits leads to Pells House right by Memorial field where much of the raged!!