Throughout the course of history, the ancient civilization of Rome has been widely discussed, praised, and emulated by writers, statesmen, and philosophers alike. Rome has no shortage of admirers, and arguably some of its most enthusiastic supporters were the American Founding Fathers who were enamoured of the Roman past largely because of Rome’s unique form of government,which had supposedly preserved liberty for hundreds of years. The Founders lavished praise upon the Roman republican heroes who defended their government from tyranny in the turbulent final days of the Republic.

Rome’s history can be split into three broad thematic periods. First, there was the founding of Rome, when kings of Rome reigned supreme. Following the removal of the tyrant king Tarquin from his lofty position, Rome became a Republic. During this Republican period, Rome rose to prominence. After conquering Italy and overcoming the Carthaginians, the Romans became the dominant power of the ancient world. Roman historians were captivated by the virtuous and selfless men who populated the rustic pastures of Republican Rome. Once the Republic fell apart as a result of civil war, the Imperial era began. During this final period, Rome was ruled by the emperors until its eventual collapse.

How Did Rome Reach America?

It may seem odd that many Americans of the eighteenth century felt any affinity towards ancient Rome, but there are many parallels between the two societies. Akin to the Republican Romans, eighteenth-century Americans were mainly rural farmers. Roman poets such as Horace and Virgil praised an agrarian lifestyle, and their writings struck a chord with the self-sufficient, hardy farmers of early America.[1] The Romans praised the virtues of independence, patriotism, and moderation which were also cornerstones of American society. During the Enlightenment, the Western world as a whole was enchanted by ancient Rome. The famous French philosopher Montesquieu once stated that “it is impossible to be tired of so agreeable a subject as ancient Rome.”[2] For a time, every educated person in the Western world had a deep understanding of the ancient past, and America was no exception. It is therefore unsurprising that Plutarch’s Parallel Lives was a consistent bestseller in America in the early days of the Republic.[3] Ancient literature was devoured by the educated elite of early America. This resulted in the emergence of a common language of classical references in the writings of the founding generation.

The American Revolution further intensified interest in the Roman world. By anchoring those arguments for freedom to ancient precedent, Revolutionary American authors aimed to demonstrate that their arguments were timeless and firmly embedded in history. Historians such as Plutarch, Livy, and Tacitus successfully encapsulated in writing the eternal and unavoidable struggle between liberty and power.[4] Parallels between Rome and America were made frequently by Revolutionary writers and orators. Josiah Quincy compared the tyrant Caesar to King George, asking “is not Britain to America what Caesar was to Rome?”[5] One of the most dramatic and obvious examples of reference to Rome was Joseph Warren’s oration on the Boston Massacre in 1775, during which he wore a Roman toga.[6] It would be difficult to find any public figure of the Revolutionary period who did not quote a classical author in their pamphlets, orations or letters.[7]

Many of the educated American Revolutionaries not only read about the Romans as a scholarly pursuit, some actively tried to emulate their behaviour and virtues. Above all else, Plutarch’s Parallel Lives and Livy’s History of Rome provided many models of virtuous and hardy Roman citizens and counter examples of licentious and indulgent tyrants.[8] Among the former were Cicero and Cato, two of the most famous paragons of Roman virtue. These men, who defended the ailing Republic until their deaths, became moral exemplars for the founding generation.

The Life of Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero was born in Arpinum outside Rome in 106 BC. In his lifetime Cicero was a lawyer, statesman and philosopher. Cicero was not typical of Roman elites. He did not come from a famous noble family and his career was not advanced through military victory. Instead, Cicero was what the Romans called a Novo Homo, or “New Man.” He earned praise through his own merit rather than by relying upon a family name. Foregoing the traditional path to success, namely military commands, Cicero made a name for himself in the courts of law through his oratory. After exposing and dismantling a conspiracy headed by a fellow Roman called Catiline, Cicero was praised as Pater Patriae, or “Father of our Fathers,” an aspirational title for an ancient society so centered on tradition.[9]

Throughout his life, Cicero had a passion for philosophy. He was eventually excluded from politics due to the tyranny of Caesar and so turned to writing philosophical treatises at a rapid pace. His philosophical works and court orations were of immense interest to the Founders, especially to those inclined towards legal studies.[10]

Cicero truly loved Rome and admired its republican form of government, which he believed was the greatest protector of liberty. He vigorously opposed Caesar’s rise to power. After Caesar’s assassination, Cicero gained a new enemy in Caesar’s former right-hand man, Marc Antony.

In opposition to Antony’s rise to power, Cicero became immortalized in history when he delivered a set of orations known as the Philippics. Condemning Antony, Cicero wrote: “Nevertheless, let us imagine that you could have killed me. That, Senators, is what a favour from gangsters amounts to. They refrain from murdering someone; then they boast that they have spared him!”[11] The Philippics remain one of the most damning condemnations of tyranny that has ever been written.

The Founders and Cicero

Cicero was praised for his selfless commitment to the common good, his towering intellect and, above all, his skill as an orator. John Adams applauded him, stating that “all ages of the world have not produced a greater statesman and philosopher united than Cicero.”[12]Adams was especially enamoured of Cicero because both men came from non-elite families, Adams being the son of a shoemaker and farmer. He saw Cicero as a model of personal merit, independent of the circumstances of his birth. Cicero’s works were frequently quoted by the Founders, as well as in various contemporary orations, pamphlets, and sermons. John Quincy Adams said that to be without Cicero “[it] seems to me as if it was a privation of one of my limbs.”[13] Thomas Jefferson listed Cicero as one of his major influences in relation to the drafting of the Declaration of Independence.[14]

The founding generation admired Cicero as a steadfast defender of liberty and a deeply philosophical thinker on the ways in which government can best preserve our naturally endowed rights and freedoms. He was referred to as a constant source of wisdom on the topic of political philosophy as well as a guide to civic virtue and was described by Josiah Quincy as “the best of men and the first of patriots.”[15] Cicero’s oratorical prowess was emulated by many early American lawyers and statesmen who wished to be as eloquent and impassioned as the man who defied tyrants.[16]

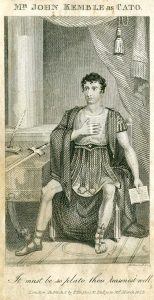

The Life of Cato the Younger

Marcus Porcius Cato Uticensis, more commonly known as Cato the Younger, was a Roman statesman born in 95 BC. He was well-known for his remarkably stoic attitude. He scorned luxury and frivolity and honored the frugal traditions of past Romans by “laboring with his own hands, eating a simple dinner, lighting no fire to cook his breakfast, wearing a plain dress, living in a mean house, and neither coveting superfluities nor courting their possessors.”[17] In keeping with this frugality, Cato walked everywhere on foot, a rarity for a wealthy Roman who could be transported by horse or carried on a litter.[18] In each post he held, he worked tirelessly to learn every relevant law and rule. Plutarch described the awe of his contemporaries, writing that “many were captivated by his persevering and wearied industry.”[19]

Cato was the quintessential republican man, selflessly dedicated to his country in his public life, and wholly committed to personal virtue. As a follower of the Stoic school of philosophy, Cato argued that the key to living a happy life was to pursue virtue above all else, which he believed comprised of right action in agreement with reason. On Cato’s personality, Plutarch wrote that he “was possessed, as it were, with a kind of inspiration for the pursuit of every virtue.”[20] His contemporary and ally Cicero praised him later in life, remarking that “Cato had been endowed by nature with an austerity beyond belief.”[21]

From a young age, Cato had a strong aversion to tyranny and a love for republican freedom. Unfortunately, he spent his formative years living under the reign of Sulla, one of the most ruthless tyrants Rome had ever seen. Sulla constantly drafted proscriptions, or lists of men who were to be slain for a hefty reward. Sulla used these proscriptions to kill men who had committed no crimes but were very wealthy, thus allowing him to expropriate their wealth. When these opportunistic expropriations became obvious in their intent, one man who had been proscribed quipped grimly: “woe is me, my Alban farm has informed against me.”[22]

Surprisingly, Cato’s father was friendly with Sulla. Because of this, Cato and his brother were often invited to visit and converse with Sulla while accompanied by their tutor Sarpedon. Sulla’s home resembled a dungeon more than an abode, with shrieks of the tortured echoing through the halls. Witnessing these horrors, the young Cato firmly asked his tutor why nobody had killed Sulla yet. Sarpedon replied that it was because people feared him more than they hated him. Enraged by the tyrant Sulla, Cato asked: “Why, then didst thou not give me a sword, that I might slay him and set my country free from slavery?”[23]

Alongside Cicero, Cato opposed the tyranny of Julius Caesar. Following the defeat of the pro-Republic faction, Caesar offered clemency to anyone who had opposed his reign. Caesar’s promise was genuine; by sparing his enemies he aimed to demonstrate his merciful character and further glorify his complete victory over the republican faction. Cato knew this, and reading Plato’s dialogue Phaedo on the immortality of the soul, killed himself in staunch defiance of Caesar’s “mercy.”[24] To Cato, the mercy of a tyrant was meaningless.

Cicero, in an attempt to explain Cato’s suicide, wrote that Cato would “die rather than to look upon the face of a tyrant.”[25] To a modern audience, Cato seems a radical figure. His unwavering dedication to his principles was so intense that he preferred to die rather than betray them. To the Founders, Cato was the last free man in Rome before the chains of imperial rule enslaved all Romans.

Cato in America

The character of Cato would reach the Revolutionary generation primarily through Joseph Addison’s play Cato, A Tragedy. In this drama, Cato is depicted as resolutely focused on his own personal virtue. At one point, Cato exclaims: “Content thyself to be obscurely good. . . . The post of honour is a private one.”[26] Cato, A Tragedy quickly became the most popular play of the eighteenth century. By 1777, it had been staged 236 times in England alone, and was the longest-running play in America until Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman, which premiered in 1949.[27]

When the Continental army was at their lowest point encamped in the miserable Valley Forge, the sick, hungry, and exhausted troops crowded into a small building to watch the play.[28] It is a true testament to Cato’s lasting appeal that his story was chosen to rouse the spirits of the desperate troops.

Cato was consistently elevated by the Founders as a model of public and private virtue.[29] Patrick Henry’s famous quote, “give me liberty or give me death,” was inspired by Addison’s Cato who exclaimed that “It is not now time to talk of aught/But chains or conquest, liberty or death.”[30]

The Importance of Role Models

For the Founders, personal virtue was essential to governance. James Madison wrote that “to suppose that any form of government will secure liberty or happiness without any virtue in the people, is a chimerical idea.”[31] Benjamin Franklin went so far as to say that “only a virtuous people are capable of freedom.”[32]

Historical figures such as Cicero and Cato were considered fitting role models not only due to their character, but because of the similarity between their predicament and that of the Founders. Cicero and Cato, faced a power far greater than themselves, but were steeled by the cause of liberty. Regardless of how history played out, the Founders viewed Cicero and Cato as heroes of freedom and enemies of tyranny.

[1]Carl J. Richard, “Vergil and the Early American Republic” in A Companion to Vergil’s Aeneid and its Tradition, ed. Joseph Farrell and Michael C. J. Putnam (New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010), 355-366.

[2]Gordon Wood, The Idea of America(New York: Penguin Press, 2011), 59.

[3]Carl J. Richard, “Plutarch and the Early American Republic” in A Companion to Plutarch, ed. Mark Beck, (New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell, 2014),598.

[4]Bernard Bailyn,The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution (London and Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2017), 25.

[5]Eran Shalev, Rome Reborn on Western Shores: Historical Imagination and the Creation of the American Republic (Virginia: University of Virginia Press, 2009), 61.

[6]Stephen Botein,“Cicero as Role Model for Early American Lawyers: A Case Study in Classical ‘Influence,’” The Classical Journal 73, no. 4 (April-May 1978): 314.

[7]Charles F. Mullett, “Classical Influences on the American Revolution”, The Classical Journal 35, no. 2 (November 1939): 93-94.

[8]Bailyn, Ideological Origins, 25.

[9]Jon Hall, “Saviour of the Republic and Father of the Fatherland: Cicero and Political Crisis” in The Cambridge Companion to Cicero, ed. Catherine Steel (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 216.

[10]Botein,“Cicero as Role Model,” 318.

[11]Cicero, Philippics II.5-6.

[12]John Adams, A Defence of the Constitutions of Government of the United States of America, I:xix-xx, xxi.

[13]Charles Francis Adams, Memoirs of John Quincy Adams: Comprising Portions of His Diary from 1795 to 1848, Vol. 4 (New York: J. B. Lippincott & Company, 1875), 361.

[14]Jeremy Bailey, Thomas Jefferson and Executive Power (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 106.

[15]Mullett, “Classical Influences,” 96.

[16]Botein,“Cicero as Role Model,”313-321.

[18]Plutarch, CatoV; A‘litter’ was a bed/chair on which wealthy Romans were carried.

[26]Fredric M. Litto, “Addison’s Cato in the Colonies,” The William and Mary Quarterly 23, no. 3 (July 1966): 445.

[27]Litto, “Addison’s Cato,” 442; Rob Goodman and Jimmy Soni, Rome’s Last Citizen: The Life and Legacy of Cato, Mortal Enemy of Caesar (New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2012), 352.

[28]Goodman and Soni, Rome’s Last Citizen,8-12.

[29]Nathaniel Wolloch,“Cato the Younger in the Enlightenment,”Modern Philology 106, no. 1 (August 2008): 60-62.

[30]Wood, The Idea of America, 73.

[31]Thomas L. Pangle, The Spirit of Modern Republicanism: The Moral Vision of the American Founders and the Philosophy of Locke (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990), 45.

[32]Gary C. Bryner and Noel B. Reynolds, eds., Constitutionalism and Rights (Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University, 1987), 16.

4 Comments

The colonists had to do a bit of reaching to equate the likes of Cicero and Cato to the North American experience. Eighteenth century England hardly posed the kind of threat that those ancients were addressing, but they certainly served as an attractive vehicle to colonists on which to legitimize their rebellion. Who can successfully argue otherwise with those who wrap themselves in the aura that classical Rome and Greece had to offer?

We need to be careful in assigning any thoughts of so-called “tyranny” to England. That was hardly the case as the Americans were not suffering from onerous English rule, but, rather, a legal system that had worked for centuries and was then in need of refinement (such as representation) in a declining, post-feudal time period. England was, in fact, solicitous of colonists’ needs and taxes were not harming them. However, a vociferous, mean-spirited cadre of alarmists (think Otis and Adams) liked to make it seem so. It was a stalking horse they were leading and the population ate it up.

Not that they even come close to Cicero or Cato, do you recognize any current day politicians trying to do the same thing to the masses? As they say, the more things change, the more they stay the same.

Gary,

I think you hit the nail on the head when it comes to objectively comparing the situation in Rome and the colonies. I also suspect that Otis and Sam Adams purposely drew the parallels to legitimize, and even ennoble, their mobilization of the mobs. I imagine it’s easier to tar and feather someone representing British authority if you can justify it in the defense of some ancient principle.

But, for now, I see differences between the use of ancient imagery and concepts for political mobilization in MA and the private references to them among Virginia’s elites, even as they feted the royal governor for promoting VA’s interests. With that in mind, the Virginians strike me as more sincere than some of their MA colleagues when it comes to employing the parallels. To be sure, I have some more study to do in that area.

In both cases, though, references to the ancients seemed to serve as common cultural and philosophical touch-points/memes that didn’t require a lot of explanation, much in the same way boomers today can refer to Kennedy’s “bear any burden” speech or King’s “I have a dream” speech and then immediately establish a common connection with an idea.

For the last 40 years, we’ve been stuck with “I am not a crook,” “Read my lips, no new taxes,” “I did not have sexual relations with that woman,” “If you like your doctor or healthcare provider, you can keep them,” etc. as common political reference points. I’d much prefer Cato and Cicero!

Nice piece Paul!

You failed to include Henry Knox’s Society of the Cinncinnatti, inspired by the twice appointed dictator, Lucius Quinticus Cinncinnatus, who, after saving Rome, both times, put down his sword and returned to his farm ! Knox felt the officers of the army were about to do the same thing. No take over of the country by the military.

I admire Cicero and Cato as much as the next guy, but this article seems to present a largely romanticized view of them. They share as much of the responsibility for the downfall of the Republic as any of the others. Cicero’s quarrels with Caesar were primarily over policy differences rather than over Caesar’s alleged tyranny, regardless of what he said to justify himself. And Cicero’s unconstitutional actions during the Catiline conspiracy, which are whitewashed here, had as much to do in setting the stage for the civil wars that finally destroyed the Republic as did anything else. The downfall of the Roman Republic was a very complicated matter, that played itself out over several generations. It’s a disservice to simplistically reduce it to the heroes Cicero and Cato vs the villain Caesar. All of these (and others as well) were great men, who are still talked about after thousands of years. They all had positive and negative aspects, and they all saw themselves as trying to salvage Rome’s doomed Republic. Rome has much to teach us, but to learn properly from it we really need an honest portrayal of its history. The richly complex reality is also much more interesting and compelling than the cartoon version.