Documents that contain the original signatures of more than one Continental Army general are rare. During the eight years of the Revolutionary War, generals penned thousands of pages of military orders, official correspondence, and private letters. The vast preponderance of these signed documents are in archives and museums, but some are cherished and preserved in private collections. Almost exclusively, however, each document contains the signature of only one general.

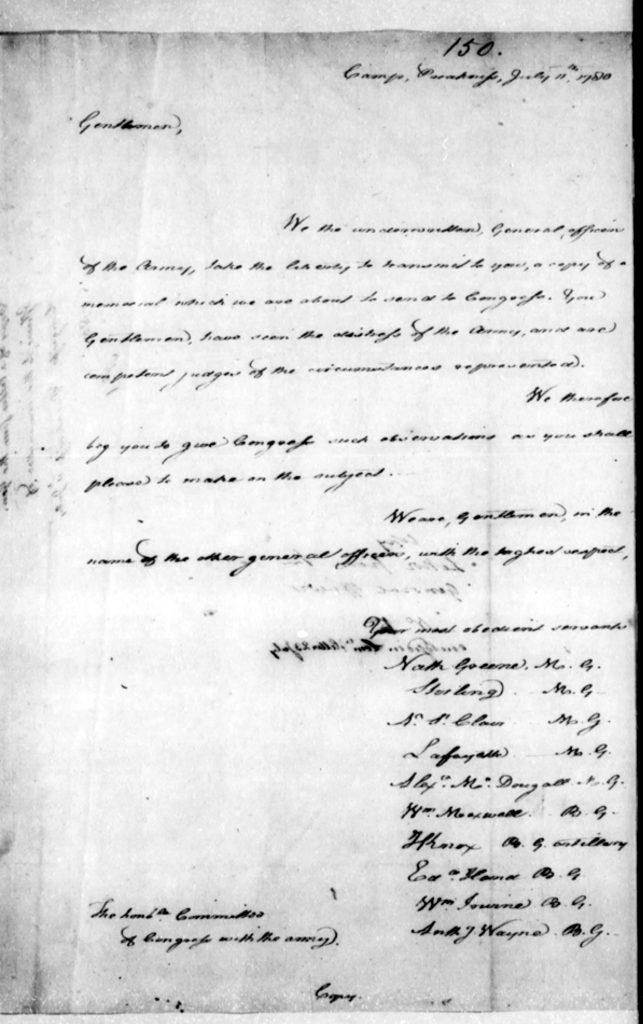

Remarkably, a single page containing ten signatures of Revolutionary generals was recently brought to the attention of the Journal of the American Revolution by a private collector (Figure 1, above). How they signed and their full ranks and names are:

“Nath Greene M. G” — Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene

“Stirling, MG” — Maj. Gen. William Alexander, Lord Stirling

“Ar. St. Clair MGl.” — Maj. Gen. Arthur St. Clair

“Lafayette M. G.” — Maj. Gen. Marquis de Lafayette

“Alexr. McDougall M General” — Maj. Gen. Alexander McDougall

“Wm. Maxwell B. G.” — Brig. Gen. William Maxwell

“HKnox Brig Genl Artillery” — Brig. Gen. Henry Knox

“Edwd. Hand B. G.” — Brig. Gen. Edward Hand

“Wm. Irvine B. Genl.” — Brig. Gen. William Irvine

“Anty. Wayne B G” — Brig. Gen. Anthony Wayne

The salutation “Your most obedient servants” indicates that the signatures at one time were attached to a letter or petition that is missing.

Ten standalone signatures on a single page raises two intriguing questions: to which document were they originally attached, and what was so important as to engender the normally-fractious general officer corps to band together as signatories?

Finding the Missing Document

Analyzing the signatures and the associated major general and brigadier general ranks bounds the time period and provides an indication of the formality of the document. Given the service dates for these ranks, the signatures and the missing associated document were prepared between October 20, 1777 and July 25, 1780.[1] Consistent with the generals’ extreme concern with hierarchy, the signatures are in military rank order except for Brig. Gen. Anthony Wayne’s at the bottom, which should be placed ahead of Brig. Gen. Edward Hand.

The second clue to the missing document is the notation at the bottom left of the signature page, “The honorable Committee of Congress with the Army,” the intended recipient of the letter. With Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene’s name at the top of the signatures, the next step was to search his meticulously edited papers for communications to Congress during this period. A search of the Greene papers yielded a citation noting the signatures of ten generals on a July 11, 1780 transmittal letter to a three-person Congressional delegation visiting the army camp providing them with an advance copy of a memorial and grievances to Congress.[2] The next task was to find the letter itself.

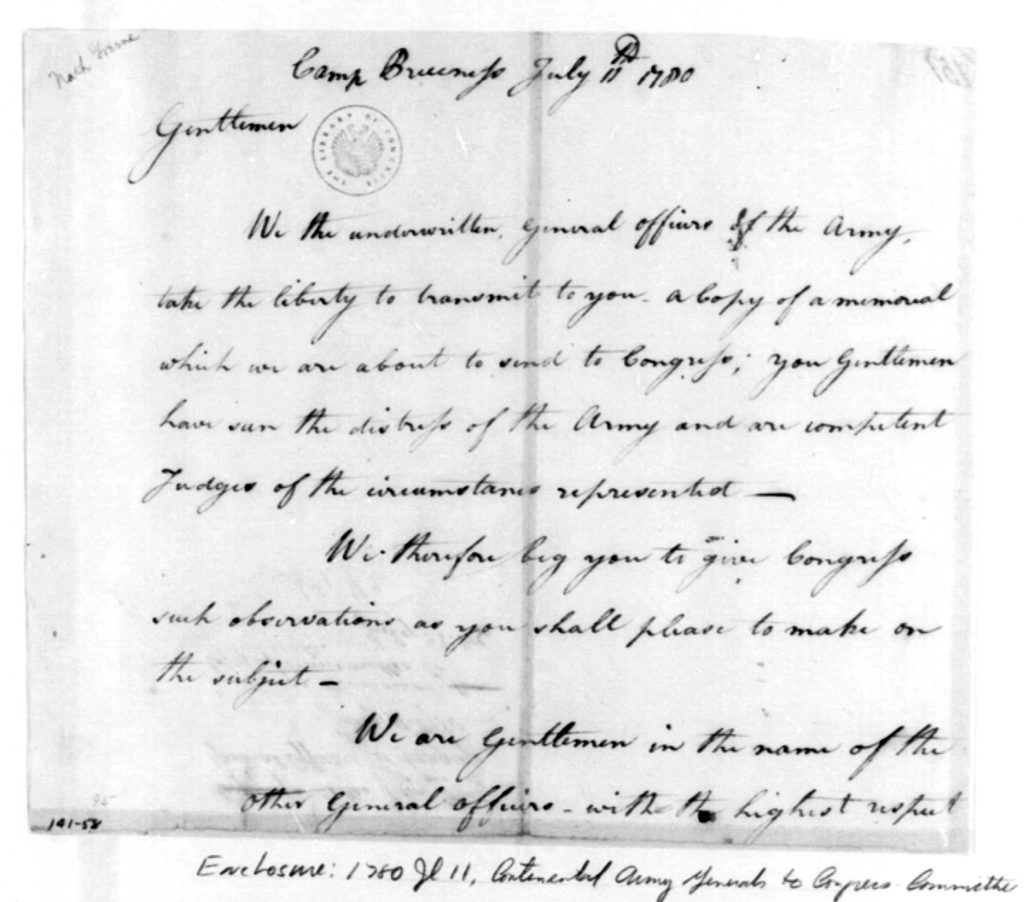

An electronic search of the Papers of the Continental Congress archived at the Library of Congress located an electronic copy of the July 11, 1780 transmittal letter to the congressional delegation (Figure 2). Interestingly, this document is labeled “Copy” at the bottom of the page and the signatures are in the same order but all in one scribe’s handwriting, denoting a secretarial copy.[3]With confirmation of a copy, now the challenge was locating the original letter.

Searching records of George Washington’s correspondence provided the final piece to the puzzle. A 1906 reference book cites this July 11, 1780 letter, with a notation that the “Signatures are missing.”[4] Using this lead, an electronic copy of the original letter was found on the Library of Congress web site, indexed as July 11, 1780 transmittal letter (Figure 3). This picture of the original letter clearly shows that the signatures are missing and the document has tear lines at the bottom.

By this archival research, the mystery of what the generals were attesting to is solved; the standalone signatures in Figure 1 were originally attached to the transmittal letter in Figure 3. At some point before 1906, the signatures were separated from the July 11, 1780 transmittal letter. Unfortunately, there is no paper trail documenting the detachment; how and why there were separated remains a mystery.

Why did ten generals band together to sign one document?

However mysterious the separation of the signatures from the letter, the underlying issue of the generals’ memorial to the Continental Congress that accompanied the letter is historically important. As the Revolutionary conflict dragged on, the generals increasingly clamored for higher pay and relief from unreimbursed expenses such as a need to own and personally support a team of horses. Depreciation of the Continental dollar was rife and most generals dipped into their own pockets to pay living and other campaigning expenses. Perhaps a bit galling for the generals, Congress provided relief to subordinate field grade officers by allotting them, but not the generals, an additional subsistence allowance of $500 per month on August 18, 1779.[5]

On November 15, 1779, twenty-eight of the forty-four generals (substantially all of the active duty generals in the north) sent an initial letter to Congress seeking what they believed was just compensation.[6] In effusively flowery language, the generals pointed out that depreciating currency had left them with less purchasing power than subordinate soldiers and, in many cases, common laborers hired by Congressional commissaries. Further, believing they should be treated similarly to British officers who received half-pay for life in retirement, the American generals requested pension compensation after the war. Although George Washington did not sign or endorse the generals’ 1779 letter, he tacitly approved.[7] Congress debated the matter, but did not act.

Increasingly frustrated as winter turned to summer, the generals conceived a three-part plan to again express dissatisfaction with pay and expenses to Congress while congregated at the Continental Army Camp in Preakness[8] in northern New Jersey. First, they drafted a less solicitous, more stridently written memorial to Congress dated July 11, 1780 stating their pay, expense and other grievances and proposed remedies.[9] Signees included all six active duty major generals located in the north, ten of the eighteen northern brigadier generals, and General Lafayette, who in an addendum indicated his support but requested no compensation.[10] While there were fewer signees to the 1780 memorial (primarily due to redeployments to the southern theater, capture, dismissal and retirements), this was a second broad signal to Congress that the general officer corps was not happy and that Congress should enact remedies. Mostly ominously, the 1780 memorial contained an open threat that the generals would resign in mass and concluded with “any ill consequences should arise their Country, they leave to the World to determine who ought to be responsible for them.”[11]

As the next step, the generals appointed Maj. Gen. Alexander McDougall to personally carry the memorial to Philadelphia, to meet with Congress in person and to seek redress for the stated grievances and economic plight of the generals. He was instructed to stay in Philadelphia until he obtained a formal Congressional response. Lastly, a three person Congressional delegation was in Preakness camp observing the army, so the officers thought best to provide them with a copy of the memorial and the July 11, 1780 transmittal letter (Figure 3, with Figure 1) seeking the committee’s support for the generals’ grievances. Noting that the Congressional delegation had seen the distress of the army, the letter stated, “We therefore beg you to give Congress such observations as you shall please to make on the subject.” This advance outreach to the Congressional delegation was helpful, as the delegates sent a recommendation to Congress to “act quickly on the demands.”[12] In a separate August 20, 1780 correspondence, Washington warned Congress the army could dissolve at the end of the summer campaign unless Congress acted quickly. He added personal support with “I have often said, and I beg leave to repeat it, the half pay provision is, in my opinion the most politic and effectual that can be adopted.”[13]

Congress did not immediately react, but took this second request more seriously. After several weeks, it provided a few low-cost items of relief such as pensions for widows and orphans of officers who died during the war, and provided an increase in rations subject to Washington’s approval. In addition, Congress pledged land grants at the end of the war of 1100 acres for a major general and 850 acres for a brigadier general.[14] However, Congress skirted the central, costly issue of officer compensation. Even with the generals’ strong language and Congress’s lack of substantive compensation changes, there were no mass resignations and not even one general left the army over pay during the next several months.[15]

Maj. Gen. Benedict Arnold’s defection in October, however, changed the views of many in Congress. Arnold had not signed any of the memorial letters to Congress but was widely known to have believed that Congress had not properly recognized his personal contributions and financial obligations that resulted from his commands. Further, a recent court martial deemed Arnold personally responsible for unsubstantiated payments incurred while in command during the 1775 Quebec campaign. As a result of heightened fears of further defections or revolt among the general officers, Congress voted to offer half-pay for life for the generals on October 21, 1780.[16]

Again, near the end of the war, compensation issues arose and became a chief issue during the notorious “Newburgh Conspiracy.” Several months before the infamous and anonymous letter calling the officers to a meeting in March 1783, Alexander McDougall delivered to Congress another memorial requesting additional compensation, this time on behalf of all the generals and field grade officers and not individually signed.[17] Dated December, 1782, this memorial included the most comprehensive demands including commutation of half pay for life to full pay for a certain period, back pay, additional funds for rations, and increased forage and clothing allowances. The memorial ended with a less-than-veiled threat of a growing insurgency within the army. As in 1780, Alexander McDougall acted as the generals’ on-site agent in Philadelphia. Similar to 1780, McDougall found a less-than-sympathetic Congress. In the end, Washington diffused the military insurgency during the famous officers’ meeting in Newburgh and there was no military takeover from civilian leadership. However, Washington’s reports to Congress on the officers’ meeting spurred action and on March 22, 1783, the legislative body commuted half pay for life to five years of full pay including six percent per annum interest.[18]

Even with this promised lump sum payment and a grant of land, the vast majority of generals died with few assets. Often, officers sold the promissory pay and land grant certificates for a steep discount. Moreover, the war devastated the productive assets of many generals and almost all were not financially successful after the war. A good example is Maj. Gen. Robert Howe, who had reservations with the mass resignation threat which “does not altogether Quadrate with my feelings.”[19] His North Carolina plantation never returned to profitability after the war, and despite a grant of special post-war Congressional financial support, he barely escaped debtors’ prison before death.[20] Many others found themselves in the same situation as Howe. Even extraordinary grants of large confiscated loyalist plantations to Nathanael Greene and Anthony Wayne by State governments did not lead to financial security for these generals, as they could not make these lands productive. Having devoted eight years to the Revolution and neglected their pre-war commercial ventures and professions, the general officers had difficulty transitioning into peacetime occupations.

At three critical points during the war, large groups of general officers sent memorials to Congress requesting pay increases, payment of unreimbursed expenses and retirement pensions. Having visions of the generals angling to become an American noble class, some members of Congress perceived these demands as inordinate, undeserved compensation. With Washington’s deft leadership and the recognition by a majority in Congress that additional compensation was warranted, the fledgling republic avoided a Cromwellian military takeover at the end of the American Revolution.

Even though self-serving, the letters and memorials are exceptional because they contain the collective thoughts and the signatures of most of the available general officers given geographical constraints. While groups of generals signed court martial verdicts (along with field officers), there are few other instances of Revolutionary generals banding together to express a point of view or to raise issues. The July 11, 1780 detached document with ten Continental Army generals’ signatures is particularly interesting when directly connected to the historically significant issue of the loyalty of the army’s senior officers to civilian oversight and control.

[1]For ranks and dates of service see, Francis B. Heitman, Historical Register of Officers of the Continental Army During the War of the Revolution (Baltimore, MD: Clearfield, 1932).

[2]Nathanael Greene, The Papers of General Nathanael Greene (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1976), 6: 84.

[3]Nathanael Greene et al., “Papers of the Continental Congress – M247 – Letters of Committee to Headquarters, 1: 150, www.fold3.com/image/438836?terms=irvine, accessed June 25, 2018.

[4]John Clement Fitzpatrick,, ed., Calendar of the Correspondence of George Washington, Commander in Chief of the Continental Army, with the Continental Congress (Library of Congress. Manuscript Division, 1906), 438.

[5]Roger J. Champagne, Alexander McDougall and the American Revolution in New York (Schenectady, NY: Union College Press, 1975), 157.

[6]“Memorial of the General Officers of the Army of the United States to the Continental Congress – Papers,” November 15, 1779, www.fold3.com/image/181780.

[7]Washington to Robert Howe, September 27, 1779, The Papers of George Washington. Revolutionary War Series (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1985), 22: 517.

[8]“Wayne, New Jersey Revolutionary War Sites | Wayne Historic Sites,” www.revolutionarywarnewjersey.com/new_jersey_revolutionary_war_sites/towns/wayne_nj_revolutionary_war_sites.htm, accessed June 26, 2018.

[9]“Continental Congress – Papers,” p259, www.fold3.com/image/184741, accessed July 9, 2018. For an easier to read transcription, see The Papers of General Nathanael Greene, 6: 80.

[10]For a listing of signatories of the November 15, 1779 and July 11, 1780 memorials, see researchingtheamericanrevolution.com/major-generals/

[11]The Papers of General Nathanael Greene, 6: 82.

[12]Champagne, Alexander McDougall, 161.

[13]“From George Washington to Samuel Huntington, 20 August 1780,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified June 13, 2018, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-02978. [This is an Early Access document from The Papers of George Washington. It is not an authoritative final version.]

[14]United States and W.S. Franklin, Resolutions, Laws, and Ordinances, Relating to the Pay, Half Pay, Commutation of Half Pay, Bounty Lands, and Other Promises Made by Congress to the Officers and Soldiers of the Revolution: To the Settlement of the Accounts Between the United States and the Several States; and to Funding the Revolutionary Debt, Online Access: HeinOnLine HeinOnline Legal Classics Library (T. Allen, 1838), 20, https://books.google.com/books?id=X9JKAAAAYAAJ.

[15]During the subsequent months, only Brigadier Generals John Nixon, William Maxwell and Enoch Poor left the Continental Army for reasons unrelated to compensation.

[16]“Journals of the Continental Congress</A> –SATURDAY, OCTOBER 21, 1780,” Library of Congress, October 21, 1780, https://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?ammem/hlaw:@field(DOCID+@lit(jc01840)):

[17]For a transcribed version of the December 1782 memorial to Congress see, Stephen H. Browne, The Ides of War: George Washington and the Newburgh Crisis, Studies in Rhetoric/Communication (Columbia, South Carolina: The University of South Carolina Press, 2016), 105.

[18]United States and Franklin, Resolutions, Laws, and Ordinances, Relating to the Pay, Half Pay, Commutation of Half Pay, Bounty Lands, and Other Promises Made by Congress to the Officers and Soldiers of the Revolution: To the Settlement of the Accounts Between the United States and the Several States; and to Funding the Revolutionary Debt.

[19]From Robert Howe to Nathanael Greene, July 14, 1780. Nathanael Greene et al., The Papers of General Nathanael Greene, Volume VI, 101.

[20]Charles E Bennett and Donald R Lennon, Quest for Glory: Major General Robert Howe and the American Revolution (Chapel Hill, NC: Univ. of North Carolina Press, 1991), 155.

11 Comments

Good research work Gene. More of this type of hard research needs to be done and presented on this site. Only those who have done research like this will understand its true value and the effort that it takes. Thanks for your contributions.

Great research! I see that Lafayette, who was supported by his king, joined in with this group. I wonder what Generals were compensated? Maj. Gen. Mordecai Gist purchased a large plantation in Charleston, SC after the War. Laffayette eventually received a substantial amount of compensation. Officers like Lieutenant Colonel Tench Tilghman made it a point to fight the entire war without a want for compensation. It would seem to show some cultural differences between the north with their soldiers who departed early from the fight into the war and the leadership of soldiers from the south that fought throughout the north and south from the very beginning to its very end.

Excellent research on an interesting topic

John Cummings…interestingly Lafayette signed the transmittal letter requesting support from the Committee of the Congress with the Army, but not the Memorial itself as he did not have the same standing to make claims for compensation. Rather he signed an attached note or addendum to the Memorial noting the difference in his standing but expressing support for the grievances and requests made by the generals in the Memorial

A debt of gratitude is forwarded to Mr. Procknow for his provocative and thorough research…..and, too, the private collector’s willingness to share an extraordinary, and valuable historic puzzle piece.

Noted, “Although George Washington did not sign or endorse the generals’ 1779 letter, he tacitly approved.[7] Congress debated the matter, but did not act.”

Legislative malaise continues unchanged, 239 years later, or so it seems.

Love this unusual piece of history, as a member of the SAR it is that more important to me. Thank you.

Congratulations on an absolutely fascinating article that provides highly instructive insights into the conduct and process of diligent research and developing persuasive conclusions. I wonder – was Arnold offered the opportunity to sign the July 1780 letter, given his well-known grievances and did he decline (he was of course knee-deep in his plotting by the summer of 1780), or was his backing perhaps seen as potentially counterproductive given his virulent enemies in Congress? Howe, Maxwell, and Knox had previously served on the Arnold court martial panel in 1779-80, which sentenced him to a reprimand for his various activities in Philadelphia, but I’m not sure how that would necessarily play into any possible decision by them to invite him or exclude him.

Thank you, Rand!

You raise a substantial question as to the absence of Benedict Arnold from the signatories. For the first memorial in November 1779, Arnold was in the process of defending himself from a court martial and would have not had the authority to sign as a general officer until the conclusion of the judicial proceedings (which happened in December 1779).

However, it was a different matter with the second memorial. During its drafting in July of 1780, Arnold resided in Philadelphia carrying on secret negotiations with the British and not in Camp Preakness with the rest of the army. The fact that he did not lend his proxy like General Parson is telling after the fact. However, I have not found anything in the historical record which raises any suspicions before his defection. At the time, It was well known that Arnold had complained directly to Congress about the lack of general officer pay and his unheeded complaints with expense reimbursement. Clearly, with hindsight, Arnold’s lack of participation could have raised some concerns. However, many of the other officers did not like Arnold, so they may not have cared to have his name on the memorial, especially with Arnold’s poor standing with Congress.

As Arnold began his correspondence offering his services to the British in May 1779, it would make sense that he no longer had an interest in the efforts of the other generals regarding compensation. He had his own plan.

His actions from that time on should have drawn attention if the Army had any counterintelligence capability – it didn’t really.

I would like to ditto Steve Darley’s comments about this article. Really nice job, Gene.

What’s interesting is a comparison of that time vs. today. My father, a Lt. Col. in the Army, told me that he remembered a time in which Congress threatened to reduce the retirement benefits of officers during the 1960’s (maybe it was late 50’s my memory is a bit faded) and according to him, the officer corps countered and threatened to form a class action suit against the Government, violation of contract. According to him Congress backed down. Don’t know all the details (he’s dead now) but that is what he told me about 20 years ago.