Upon our arrival, I did behold a most curious Sight, which gave me further Cause to wonder about the true Safety we might here enjoy. Above the entrance to the Harbor of this town there stands upon the Gibbet a most piteous set of remains, being the last mortal pieces of a most heinous Criminal, lately caught in these parts. He was known as Jack the Painter, and upon declaring his attachment to the Violent Cause of Rebellion in America that we have just escaped, he did undertake to commit Acts of destruction upon these shores. He succeeded only in firing the rope-house at the Royal Navy’s great Shipyards here, but even that caused a great Disruption and Upset in these parts. It comes as small Comfort to my distressed Mind that he was captured in due course, and brought to a Swift and certain End, his corpse left to Dangle here as a visible Warning to all who might Conceive of a mis-placed Notion to follow his example.

The Break, Tales From a Revolution: Nova-Scotia

The mizzenmast of HMS Arethusa rose over sixty-four feet high into the spring morning, forming a gallows the likes of which had never before been seen on England’s fair shores. It had been unbolted from the ship where she lay at anchor in Portsmouth harbor, and raised for this purpose both to enable the unprecedented throngs to witness the fate of the condemned, and also because his crimes were felt to have been a particular assault upon the Royal Navy.[1]

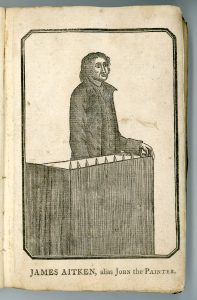

James Aitken, a disheveled-looking, redheaded Scotsman, was drawn in chains on a wagon toward the site of his impending execution, and his date with infamy. Most of the residents of Portsmouth, and more from the surrounding towns crowded into the public square, amounting to as many as 20,000 witnesses to this moment in history.

As Aitken neared the gallows, his wagon was directed to pass by the burnt-out ruins of an immense structure within the walls of the naval storeyard. The prior fall, it had bustled with activity, as scores of workers labored within its walls, winding and twisting mile upon mile of hempen rope for His Majesty’s ships’ rigging and anchors. The lines that had issued forth from the now-ruined building had helped the Royal Navy impose a cordon around the ports of rebellious cities in the American colonies, and the loss of this facility was but one stroke in a series of attacks to further impede the ability of the navy to impose the King’s will upon his unruly subjects across the sea.

What thoughts must have passed through Aitken’s mind as he looked one last time upon the culmination of many months’ planning? A sense of satisfaction, perhaps, that he had been able to succeed at the plot? Or disappointment that he had been foiled in accomplishing more that he had planned, by chance and by the spreading terror that he had, in fact, sought to cause? Or, perhaps, a sense that he had at last risen above the difficult years of his childhood and the habits of petty crime into which he’d fallen, to commit acts which had inflamed the sentiments of the British public against the American cause, and had, in some measurable way, changed history?

Alternatively, were his thoughts no more orderly than those of any other madman, filled with self-important aggrandizement of his role in sowing terror across England, from her shipyards to the seat of power? It is impossible to know with complete certainty, but he left behind an uncharacteristically rich record of how he wanted posterity to think of him.

James Aitken (variously known as “John,” “Jack the Painter,” “John the Painter,” and a variety of aliases that he adopted throughout his career including James Hill, James Boswell, and James Hinde) was born in Edinburgh in 1752, the eighth of twelve children in a large Scottish family. When he was still just a boy, his father died, and John was admitted to a charity school set up by George Heriot for the benefit of fatherless children. Intended to give such unfortunates the advantages of a top-notch education, it was a relatively strict, if effective, institution.

Aitken spent his days in regimented studies and devotions, lasting from seven in the morning until eight at night. Time was provided for “innocent diversions” and “visiting with friends,” but these privileges could be revoked for bad behavior. [2]

However, his apprenticeship with a painter was unfortunate. The market for house painters was both saturated and shrinking in 1767, when he started his career.[3]Although he clearly absorbed the practical aspects of his craft, John just as clearly found it difficult to support himself.

To supplement his income as an itinerant worker, he turned to crime, stealing from shops, travelers, and homes. Worse, he later admitted to having raped a woman who was alone with her sheep in the countryside.[4]During this period of his life, he clearly developed the habit of taking what he wanted, without regard for anything resembling what his peers might have considered moral or right.

As did many who had a criminal background for which they wished to escape prosecution, he decided to leave behind known hardships of home for the unknown opportunities of the colonies, signing on as an indentured servant. He failed to find the riches and ease he sought on these shores, and though the historical record is silent on his exact activities in America, he later claimed to have traveled fairly extensively through the colonies.[5]

This was the mid-1770s, and revolutionary fervor was rising among the restive colonials. Many of the newspapers and pamphlets that he would have encountered on the streets and in the shops rang with denunciations of the King and Parliament, as well as lurid tales of the depredations of British troops who were sent to quell their rowdy subjects.

By the time Aitken returned to England, open rebellion was at hand in the colonies, and he began to devise a plan to make his mark on history, while striking a blow against the society that he blamed for his own hardships.

He had pretty clearly lost his fear of capture, either because enough time had passed since his youthful misdeeds that he did not expect anyone to be looking for him anymore, or because his appearance had changed with a few years’ maturity.

In any event, he apparently traveled throughout Britain, and even went so far as to visit Paris; what means of support he found for these activities is unrecorded, but his earlier career leaves us with little doubt that he continued to pursue a variety of criminal activities.

In Paris, he sought and received an audience with the American mission there. He met with Silas Deane – who was there primarily to convince the French to enter the war fully in support of the United States – and the American apparently listened with a mixture of disbelief and interest to the young Scotsman’s wild scheme.

Aitken laid out an elaborate plan of attacks, starting with a campaign of arson against British naval bases up and down the coast, throwing in attacks elsewhere as necessary to sow terror and confusion throughout the nation.

His background as a painter’s apprentice taught him the many opportunities for flaming disaster attendant to that line of work, and his preparations reflected that. However, he would take additional, fiendishly inventive steps to ensure the success of his plans.

Building on the painters’ techniques of grinding pigments into fine powders, he would produce readily-ignited charcoal powder, which he would use to spread the flames. However, to solve the problem of starting a fire and still escaping the hoped-for conflagration, he had assembled a device that featured a candle in a box to serve as a sort of timed fuse, with a base filled with turpentine; the theory was that as the flame burned down to the level of the highly flammable fluid, an explosion would result, spreading fire to all that surrounded the device.

He is thought to have shown this infernal device to Deane, as he made the case for official (even if clandestine) American support for his plan. Deane appears to have taken the young man’s measure, and concluded that his scheme had little chance of success, but that if Aitken did pull it off, he would, indeed, significantly affect the progress of the war.

While he did not give the Scotsman everything he asked, Deane did offer American support to the plan in the form of a few pounds in cash, but he also gave Aitken a passport in the name of the King of France, executed by the Comte de Vergennes, assuring his safe passage back to England.[6]

Aitken returned across the English Channel and hired a couple of tinsmiths to build a number of the devices he’d designed; only a single shop came through for him, though, and he had to content himself with just one incendiary device.

The events after this point are related in Aitken’s own jailhouse confession. On the 5th of December 1776, Aitken arrived in Portsmouth and began his reconnaissance. He snuck into the dockyard there, and first set up his device in storehouse, having soaked a bale of hemp with turpentine and gunpowder. He did not ignite it, however, as he wanted to see whether he could arrange for an even larger conflagration elsewhere in the sprawling facility.

He found a likely-looking spot in the ropehouse, an immense structure over 1,000 feet long, where rope was braided from individual threads of hemp into the monstrous lines used to work the Royal Navy’s warships. Here was a target worth investing some time in, and Aitken later said that he set a careful tinder pile, again adding turpentine and powder.

When he attempted to light it, however, the tinder was too damp, and he spent so long trying to start the fire that he found himself locked into the structure. He abandoned the attempt for the night, and had to pound on the door until he could convince someone to let him out. His credulous rescuer believed his story of innocent curiosity, and Aitken was able to return to his lodgings for the night.

After attempting (and failing) to set fire to his boarding house, Aitken was able to again gain access to the warehouse and ropehouse. This time, he was able to light his device (though the hemp around it prevented it from working) and the tinder he’d set up the prior day – it was a complete success, from his point of view.

As he hurried out of the dockyard before the fire could be detected, he bumped into an acquaintance, and was so worried that he’d been recognized that he decided to flee the city entirely. He was able to see the dockyards ablaze as he departed, and it was with some self-satisfaction that he reported to the contact that Deane had given him.

There, he met with another great disappointment, however, as the shocked Dr. Bancroft – a double agent[7]in London – not only said that he had heard nothing of the plot from Deane, but was, in fact, a faithful subject of the British Crown. Bancroft turned him out, for fear of being exposed as an American spy, and Aitken drafted a warning to Deane that the Bancroft could not be trusted.

Despite not having been rewarded with the riches he hoped for, Aitken moved on to Plymouth, where he hoped to expand upon his reign of terror. There, he found security tightened in response to the fire at Portsmouth, and after an abortive incursion into the dockyard there, he fled to Bristol.

There, he set several incendiary devices in one night, all of which failed, but the townspeople were now on edge. When another device did succeed in burning down several warehouses, the resulting uproar spawned arrests and copycats, continuing long after Aitken was far from town. Fear rose that Bristol had been targeted by a coordinated conspiracy of Whigs favorable to the American cause.

The panic spread when Aitken’s original failed incendiary was discovered buried in the hemp at Portsmouth, and a rash of what might have been ordinarily dismissed as normal misfortunes were conflated into a French or Spanish plot – or an American one.

Alarms were raised at ports all over Britain, and huge rewards of £500, and then £1,000 were posted. The response in Liverpool was typical:

… it was resolved that a strong and efficient watch be set every night from five o’clock in the evening, till seven o’clock in the morning, to patrol round the docks and through the town. Owners, masters, and others interested, were recommended to have their ships carefully watched, the persons in charge not to be allowed any candle-light or fires aboard during their watch … A strict lookout was kept on all loitering persons being in or coming into the town, and the inhabitants who had lodgers whom they eyed with suspicion, were invited to impart those suspicions to the authorities – an excellent opportunity to settle old scores.[8]

By the time Aitken’s luck ran out, in the aftermath of yet another bungled burglary, the reward for his capture had risen to well over £2,000 in all, and he was finally taken in by a jailer who had recognized him since he had been casing the last shop he burgled.[9]The jailer was unjustly cheated out of his reward by a strategic prosecution who relied on charges related to the crimes committed beforethe rewards were posted.[10]

Between Aitken’s arsonist tools – which were found on him – and the testimony of an acquaintance who had seen him in Portsmouth in the wake of the fire there, Aitken’s fate was little in doubt, and his conviction and sentence were a foregone conclusion by the time the court met for his trial.

In the days before the trial, Aitken was at first wildly uncooperative, even refusing to give his correct name. Once he became convinced that he was bound for the gallows, he was persuaded by a publisher to dictate his entire confession in exchange for money to improve his conditions of imprisonment.

This confession was not only a means of answering the many questions raised by his deranged actions (and putting some money in the pocket of the publisher), but also doubtless served to allay the fears of the British people that they were under attack on their own soil.

His unlikely “last words” were published along with this confession:

Good people, I am now going to suffer for a crime, the heinousness of which deserves a more severe punishment than what is going to be inflicted. My life has been long forfeited by the innumerable felonies I have formerly committed, but I hope God, in his great mercy, will forgive me; and l hope the public, whom I have much injured, will carry their resentment no further, but forgive me, as I forgive all the world, and pray for me that I may have forgiveness above. I have made a faithful confession of every transaction of my life from my infancy to the present time, particularly the malicious intention I had of destroying all the dock yards in this kingdom, which I have delivered to Mr. White, and desired him to have printed for the satisfaction of the public. I die with no enmity in my heart to his majesty and government, but wish the ministry success in all their undertakings; and I hope my untimely end will be warning to all persons, not to commit the like atrocious offence.

James Aitken’s actions likely helped to inflame the passions of the British people against their American cousins, and rather than helping the movement toward American independence, his violence gave the Colonies’ enemies in Parliament the support they needed to prosecute the war with even more vigor.

In the end, just as in more recent history, Aitken’s terrorism failed to convince anyone of the justice of the cause in whose name it was undertaken. It did, however, serve to increase the perception among the British people that the cause of American independence was a mortal threat to their personal safety and security. For all his claims to have been striking against Britain on behalf of America, Aitken likely did us far more harm than good.

[1]”Dockyard Timeline: 1776 – Jack the Painter,” Portsmouth Royal Dockyard, 2015, accessed January 16, 2016, portsmouthdockyard.org.uk/timeline/details/1776-jack-the-painter.

[2]Regulations for George Heriot’s Hospital(Edinburgh, 1795), 25-27, books.google.com/books?id=oSJeAAAAcAAJ, accessed April 2, 2018.

[3]Jessica Warner, John the Painter: Terrorist of the American Revolution: A Brief Account of His Short Life, from His Birth in Edinburgh, Anno 1752, to His Death, by Hanging, in Portsmouth, Anno 1777: To Which Was Once Appended a Meditation on the Eternal Foolishness of Young Men(New York: Thunders Mouth Press, 2004), 32.

[4]James Aitken, The Life of James Aitken, Commonly Called John the Painter, An Incendiary Who Was Tried at the Castle of Winchester on Thursday the 7th Day of March 1777 and Convicted of Setting Fire to His Majesty’s Dockyard at Portsmouth, Exhibiting a Detail of Facts of the Utmost Importance to Great Britain(London: J. Wilkes, 1777), 32, books.google.com/books?id=-BNlAAAAcAAJ, accessed April 2, 2018

[7]Thomas J. Schaeper, Edward Bancroft: Scientist, Author, Spy. (New Haven:: Yale University Press, 2011), 54.

[8]Gomer Williams, “Privateers of the American War of Independence.,History of the Liverpool Privateers and Letter of Marque: With an Account of the Liverpool Slave Trade(New York: Routledge, 2013), 8.

Recent Articles

That Audacious Paper: Jonathan Lind and Thomas Hutchinson Answer the Declaration of Independence

Supplying the Means: The Role of Robert Morris in the Yorktown Campaign

Revolution Road! JAR and Trucking Radio Legend Dave Nemo

Recent Comments

"Texas and the American..."

Mr. Villarreal I would like to talk to you about Tejanos who...

"Trojan Horse on the..."

Thank you Eric! I should say that I have enjoyed your work...

"Trojan Horse on the..."

Great article. Love those events that mattered mightily to participants but often...