For many Americans, their only knowledge of galleys and the men who rowed them comes from movies such as Ben-Hur. Suffice it to say, movies’ depictions of galleys and their crews are often historically inaccurate. But there is a more significant historiographical gap regarding galleys than movies having presented a false depiction of galley crews: the noticeable paucity of scholarship on Royal Navy galleys during the American Revolution.[1] Given that galleys were small, typically having crews of thirty to forty men, rarely played central roles in important naval battles, and were either sold or broken up by 1786, this lack of academic interest is not unexpected. An analysis of the role of Blacks on British naval galleys during the American Revolution shows that the Royal Navy was “brutally pragmatic” in how it employed men of African ancestry and demonstrates that, in their treatment of Blacks, officers of galleys generally adhered to customs of the regions in which they served.[2]

Use of Galleys

At the start of the American Revolution American Rebels lacked a standing navy. Although they were ultimately successful in building a small fleet of frigates, Rebel naval forces were predominately shallow-draft vessels such as whaling boats, barges and galleys.[3]The American galleys had considerable success in shallow waters with commanders using knowledge of local waters to capture larger British ships, as did Capt. Ebenzeer Dayton, when in April 1778 his three armed galleys captured the British sloops Fanny and Endeavour in New York’s Great South Bay. More impressively, in October 1776, Benedict Arnold’s deft employment of row galleys in his small flotilla of vessels on Lake Champlain was critical in his ability to fight Gen. Guy Carelton’s far larger fleet of twenty-five armed ships, four hundred batteaux and numerous Native American canoes.[4]

Although British men-of-war ships enabled the movement of tens of thousands of troops and the capture of major cities, vessels that could maneuver in North America’s coastal waters were needed to compete with American shallow-draft vessels. Whaleboats, barges and galleys were regularly used by British forces in North American waters to conduct raids and attack American positions.[5] Even in major campaigns, such as the 1778 capture of Philadelphia, galleys and barges played a critical role in clearing inland waters, in this case the Delaware River, to permit the movement of larger men of war.

Particularly during its campaigns in the Carolinas and Georgia (1776 – 1783), the Royal Navy relied upon galleys. Ironically, Royal Navy galleys were captured from American forces or purchased from private sellers, not built at the Royal dockyard in New York. Obtaining galleys was critical for the Royal Navy as American forces were said to have “very considerable Armed Naval Forces” built expressly for the purpose of “protecting and defending” southern lakes, rivers and inlets.[6] To counter Americans’ local knowledge of shallow coastal waters the Royal Navy recruited Blacks, enslaved and free, to maintain, crew and pilot the galleys. In doing so, the navy understood that in the Americas prior to the Revolution, enslaved Blacks regularly rowed barges and galleys, and could do so for the King. The four Negroes whom Rhode Islander John Brown hired for “8 days rowing the Barge” were unremarkable in that it was common for Blacks to do such work in the Western Atlantic.[7]

Nature of Galley Crews

Black maritime workers were crucial in order for galleys to operate. Enslaved maritime artisans worked regularly to keep Royal Navy galleys in waters off the Carolinas, Georgia and Florida in working condition. For example, in October 1780 Paul Pritchard hired fourteen Negro Carpenters and Caulkers to the Royal Navy to refit HM Galley Adder at Hobcaw, South Carolina. Similarly, the Navy relied upon enslaved maritime artificers, men like Punch and Lewis, to keep HM Gally Arbuthnot and their other galleys in the southern North American waters sea-worthy.[8] Earlier in 1780 twenty-seven enslaved caulkers and shipwrights, including Tom, Dennison Sambo, Punch, Cork and twenty-four other black artisans, entered onto HM Galley Scourge at Hobcaw to repair the vessel. The Royal Navy utilized enslaved carpenters, caulkers and shipwrights not only in the Carolinas and Georgia, but in St. Augustine as well. In its considerable use of enslaved artisans to maintain its galleys the Royal Navy was, as it had been in the Caribbean throughout the eighteenth century, reliant upon Black labor to keep its vessels afloat.[9]

Black pilots were also critical to Royal Navy galleys’ operations. Pilots occupied a singular place in maritime hierarchy by controlling ships despite not being officers. By doing so, they inverted the usual American white-black social hierarchy and were threatening to white naval officers. Despite this threatening inversion of social conventions, black pilots operated throughout the western Atlantic, steering valuable merchant ships, boats, and Royal Navy men-of-war through dangerous shallow waters. Naval officials and other whites accepted this inversion of established racial hierarchy because pilots of African ancestry had particular knowledge of American waters and navigational skills that made them, in the words of one British official, “capable of Conducting the Fleet safe.” Their service in the Royal Navy included directing its galleys in North American waters. For example, between 1779 and 1788 there were not less than five black pilots – Webster, Jermmy, Johannes, Dublin and Boomery – aboard HM Galley Scourge as it operated along the southeast coast of North America. Similarly, in 1781 a “Negro Man named Trap” was hired onto HM Galley Fire Fly to serve as its pilot in Georgian waters. Black pilots directing the operation of the King’s galleys was an exception to the usual circumstance in the Royal Navy, i.e., that Blacks rarely obtained officer status or positions of authority.[10]

Other European navies often employed slaves, seamen who failed to appear for compulsory naval duty, religious dissenters and captured enemy seamen to row their galleys. Enslaved men, such as Pedro, Francisco and Domingo, could be regularly found working on French, Spanish or Portuguese galleys. Maritime historians traditionally associate service on galleys with marginalized peoples, not something most think of when considering the lives of seamen of the Georgian Royal Navy. Instead, as N.A.M. Rodger noted about the medieval Royal Navy, most historians have believed Royal Navy oarsmen were “not slaves but free men.” But in fact, slaves did work on Royal Navy galleys during the American Revolution. Fewer than five percent of all Royal Navy crewmen on the North American coast during the American Revolution were black, but there were more than twice as many Blacks on Royal Navy galleys in the waters off Georgia, the Carolinas and Florida – 12.3% of such crews.[11]

Why did Blacks work on Royal Navy galleys during the American Revolution at twice the rate they worked on other Royal Navy vessels? A review of galley musters and related documents indicates three reasons for this: the hiring out of slaves to the Royal Navy by Loyalists; impressment of free black seamen by galley commanders; and fugitive slaves seeking freedom.

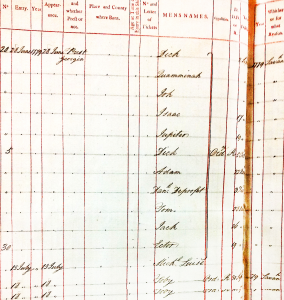

With the turbulence of war disrupting the slave economies of Georgia and the Carolinas and large numbers of slaves running away to take advantage of freedom offered them pursuant to Dunmore’s Proclamation, Loyalist slave owners sought certainty and profit by hiring out bondsmen to the Royal Navy. Admittedly, doing so meant risking losing their investment in their slaves should the bondsmen die, be captured or desert. But many of these Loyalists would have been familiar with such risks; hiring slaves onto privateers, patroons and merchant ships was a common practice in North American colonies prior to the American Revolution. This would have made some Loyalist slave owners, in a world of increasing chaos in which both British and American forces regularly took slaves from plantations, predisposed to the reasonable risk of having the King pay a regular wage for bondsmen.[12] To cite but one example, when HM Galley Cornwallis was captured in 1780 by the American privateer brig Ariel, seven enslaved oarsmen were found on board. Dick, Joe, Andrew, Ceaser, Thomas Carey, Perter and Hamden were hired out to the Royal Navy by six different Virginian slave masters. These Loyalist Virginians hoped to benefit from their slaves rowing for the King. Due to the Cornwallis being captured these six slave masters instead lost their bondsmen. The unfortunate Black sailors were, however, the real losers in this circumstance, as they were sold as prize goods in Porto Rico, returning them into enslavement in an unfamiliar environment far from family or friends. Thus, it was Black seamen who bore the greatest risk of service on galleys, not their slave owners.[13]

The unattractiveness of service on galleys is evident from the extraordinarily high desertion rates from these vessels. During the wars of the long eighteenth century the Navy’s overall desertion rate “hovered around 7 percent,” although during the American Revolution there was a spike above ten percent.[14] Thus, when Lieutenant James Every commanded HM Galley Adder from 1780 to 1783, during which time over nineteen percent of the galley’s crew deserted, he may have felt unlucky as he suffered almost twice the Navy’s usual rate of runaways. Yet among galleys in North America during the Revolution, the Adder had the lowest desertion rate. Andrew Law, during his difficult year commanding HM Galley Comet, saw seventy-eight percent of his crew flee, while the unfortunate Tylston Woolam, commander of HM Galley Vindictive, lost ninety percent of his crew. Woolam was only able to keep the Vindictive operating by impressing almost his entire crew in southern ports.[15]

Among the sixteen Royal Navy galleys on the North American station for which musters could be located, the average desertion rate was 51.8%, with the eight galleys operating in southern waters averaging 53.7%.[16] These high desertion rates undoubtedly reflect seamen’s dissatisfaction with work on galleys. Unlike on a man-of-war, where “the whip of the lash contributed little to” the often “intricate tasks on a sailing vessel,” brute force was more often the rule on galleys.[17]

Despite galleys’ critical role in supporting troops along inland and coastal waterways, the need for precise sequencing of rowing resulting in disciplining of crew, the physical demands of galley service, the infrequent obtaining of prize monies by galley crews, and the lack of shelter for most seamen on galleys, made assignment on these vessels unattractive to many seamen. The lack of appeal of service on naval galleys can be seen by the not insignificant number of elderly mariners who served on such vessels. The presence of elderly seamen in a particular maritime job, be it cook or galley oarsman, was a “mark of exceptional poverty,” as older men who normally would have shifted to less physically demanding land-based jobs were compelled to continue to go to sea and work at jobs other mariners avoided.[18]

On some Royal Navy galleys, it appears that old men were employed as a last measure when commanders were unable to maintain full complements. For example, during 1782 HM Galley Arbuthnot had experienced a greater than eighty percent desertion rate. In December alone, eighteen sailors, or over one-half of the galley’s crew, deserted. In January 1783 Lt. Tylston Woollam became the galley’s commander. With desertion rates remaining extremely high in April 1783 Woollam took on board the Arbuthnot seven elderly sailors: forty-year-old Hugh Sherrard, forty-six-year-old William Gianes, forty-seven-year-old John Shabar, forty-year-old Thomas Black, forty-five-year-old John Close, forty-year-old Francis Roberts and forty-one-year-old John Bevan. They joined forty-year-old Thomas Arbuthnot, forty-two-year-old John Rusdale, forty-eight-year-old Dennis McCarty, forty-four-year-old Peter Farleigh and forty-eight-year-old John Ball. Such older men were hardly ideal galley crew members. And as they comprised thirty percent of the galley’s forty-man complement, Lieutenant Woollam’s choice in having these elderly men come aboard the galley evidences his rather desperate attempts to complete the manning of his vessel. The galley Adder similarly relied upon elderly men to fill its complement. While operating off of South Carolina in 1780 and 1781, eight men fifty years of age or older served on the galley, the oldest being William Lynch, a seventy-four year old seaman. The Adder’s reliance upon old salts became even more extreme in 1782 when eighty-three-year-old Joseph George became a member of the galley’s crew.[19]

It is against this background of most seamen not wanting to work on galleys and slaves being hired onto these vessels that one needs to consider the impressment of free Black seamen onto Royal Navy galleys during the American Revolution. Leading maritime historians have asserted “impressment was a step up for many Black seamen.” This “step up” was in large part because, within the Anglo-American Atlantic, captured black sailors were assumed to be slaves, whether they were or not, making them vulnerable to being treated as prizes and sold into slavery. As Gov. Robert Hunter of New York observed in 1712, when black seamen were captured by British ships the men were sold into slavery as prize goods “by reason of their colour.” This presumption would be applied by British Admiralty Court officials throughout the Atlantic and some officials would continue to utilize this standard at the end of the eighteenth century.[20] When impressed onto naval vessels Blacks were provided with equal wages and protected from enslavement and the anxiety that possible enslavement caused for seamen of African ancestry. And yet while it was undoubtedly true that coerced naval service could be an improvement for Blacks, particularly for enslaved seamen, stressing this overlooks that impressment could, and in fact did, act to worsen conditions for many free Black seamen on galleys during the American Revolution.

White sailors were often protected against press gangs by local residents willing to engage in violent confrontation with the gangs. There were hundreds of such affrays in the second half of the eighteenth century.[21] The fear of becoming “Impressment Widows” lead women to take to the streets to protect their husbands and lovers. However, when Blacks were impressed, few whites were willing to confront press gangs on their behalf. And their family and kin doing so would have been dangerous, particularly in slave colonies such as Georgia, the Carolinas or East Florida.

Impressment was often described by white seamen as a form of “galley slavery” common to that in Turkey or Algiers.[22] In Tory Georgia impressment of slaves was seen as a necessary measure to deal with the threat of Rebel forces. By 1780 Loyalists were required to furnish, as needed, slaves to the royal government. Most worked on building and maintaining fortifications, but others, as did one group of 134 slaves, dragged row-boats over land, while others rowed on galleys.[23]

Impressed free black seamen could be found on many of the navy’s galleys. Scipio Cornelius, Prince William, Neptune Chance and America Shipjack on HM Galley Delaware, Prince Vaughan on HM Galley Vaughan, Polydore, Dublin, James Dick and Thomas Arbuthnot on HM Galley Arbuthnot, Hercules Romney on HM Galley Comet and Thomas Prince on HM Galley Scourge all found themselves compelled by press gangs to serve the King. It was, however, the experience of impressed free black sailors on the galley Vindictive that best illustrates the scale of impressment of free Blacks onto naval galleys and how men of African ancestry resisted coerced labor at sea. In 1779, while in waters off Georgia, the Vindictive twice impressed groups of free black seamen. First on June 28 and then again on September 10, the galley’s commander, Lt. Tylston Woollam, had free Blacks impressed at Savannah onto the galley. These press sweeps resulted in a vessel in which the entire crew was black and its officers were white. Of the thirty free Blacks impressed onto the Vindictive, all but Michael Luise, Illasure and Harry deserted the galley when the vessel returned to Savannah, many doing so within two days of the galley docking. It is likely that the twenty-seven seamen of African ancestry who fled the galley shared John Marrant’s view that being impressed caused a “lamentable stupor” that left them “cold and dead.”[24] The deserting black seamen undoubtedly were tired of being forced to work in what they must have considered to be slave-like conditions. But they also probably were weary of Lieutenant Woollam’s command, which they likely experienced as inept. Unlike other galley commanders in North American waters, such as John Brown and Sidney Smith, who went on to distinguished naval careers as admirals, Lieutenant Woollam never rose above commanding a galley, never passed the lieutenant’s exam and after the Revolution never again served in the Navy.[25]

Not compelled to row:

There was one group of Blacks serving on Royal Navy galleys who were not “compelled to row”: runaway slaves. For fugitives, service on a Royal Navy vessel, even a galley, could result in permanent freedom.[26] In less than two weeks in July 1782 Quash, Ned, Billy, Harry, Sam, Ceasar, Joco, Jacob, Snow, London, George, Jack and Bristol all “deserted from the Rebels,” i.e. fled their South Carolinian masters, and made their way onto HM Galley Adder.[27] Given that the Adder at this time only had between eighteen and twenty men, without the thirteen runaways the galley could not have operated against American forces. Some of these men deserted from the Adder, finding, like the impressed free Blacks on the Vindictive, that service on a galley was not to their liking. But others, such as Quash, Ned, Billy and Harry, subsequently found themselves discharged at St. Augustine as free men. For these former bondsmen, as for hundreds of Black Loyalists, the Royal Navy served as taxi cab to freedom.

Unfortunately, runaways who served on galleys could also find themselves “returned to [their] owner[s].” A number of former slaves, having found freedom on naval galleys, lost their freedom when the vessels returned to ports from which they had fled. Thus, in November 1779 when HM Galley Scourge returned to Port Royal, South Carolina, Prince, Coffee and seven other blacks on the galley were returned to enslavement when their former masters came to the wharves to reclaim them. The Scourge was hardly the only naval galley which returned runaways to their masters. In 1783 HM Galley Arbuthnot impressed many of its crew while in Savannah and St. Augustine. Two years later, James Dick, an African-born able-bodied seaman, Nicholas March and Thomas Black, St. Augustine-born seamen, were all discharged at St. Augustine for “being a Slave.” Dublin and Polydore were similarly discharged from the Arbuthnot at St. Augustine. As were other black Royal Navy seamen who were discharged “for being a slave,” these Black sailors were returned to their slave masters despite having served in the Royal Navy for more than two years. In returning runaways to their Loyalist owners the navy reinforced Georgian and Carolinian slave culture. Thus, while fugitives from “Rebels” might have found service on galleys an avenue to freedom, many runaways from Loyalists achieved only temporary freedom from enslavement by their time on navy galleys.[28]

Conclusion

If there was a clear glass ceiling for Blacks in the Georgian Royal Navy such that obtaining the post of captain was achieved by only by one exceptional Black sailor in the eighteenth century, a similar but reverse dynamic worked when it came to avoiding one of the most difficult naval assignments – rowing a naval galley. As the musters of the Scourge, Vindictive and other Royal Navy galleys operating in North American waters indicate, whites did all they could to avoid working on galleys while Blacks found themselves impressed or hired out for such back-breaking work, and runaway slaves who entered navy galleys often found themselves re-enslaved. In this, as in many other avenues of life in the British Atlantic, Black seamen were often disadvantaged solely due to their dark skin.[29]

[1] For example, there is no discussion of British eighteenth century naval galleys in N.A.M. Rodgers’ The Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain, 1649-1815 (New York: W.W. Norton, 2005).

[2] Simon Schama, Rough Crossings: Britain, the Slaves and the Atlantic Revolution (New York: HarperCollins, 2006), 13 and 168; Charles R. Foy, “The Royal Navy’s Employment of Black Mariners and Maritime Workers, 1754-1783,” International Maritime History Journal, 28, no. 1 (Feb. 2016), 6-35.

[3] The Continental navy only had thirteen ships, all of which were by 1778 out of commission.

[4] Naval Documents of the American Revolution (“NDAR”) (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1962-), 5:1 and 6:1237.

[5] George E. Buker and Richard Apley Martin, “Governor Tonyn’s Brown-Water Navy: East Florida during the American Revolution, 1775-1778,” The Florida Historical Quarterly 58, No. 1 (Jul. 1979), 58-71.

[6] Prescott to Lord Cornwallis, Nov. 22, 1779, Cornwallis Papers, PRO 30/55/20/41, The National Archives, Kew, England (TNA); Georgia Executive Council, Apr. 3, 1778, NDAR 12:28-29.

[7] John Brown Papers, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, AM 8180, p. 12.

[8] HM Galley Adder Muster, 1780-1782, ADM 36/10384, TNA. When and where the Royal Navy employed enslaved maritime artisans was largely a function of local customs, environmental conditions and whether white artisans were available. Foy, “The Royal Navy’s Employment of Black Mariners and Maritime Workers, 1754-1783,” 6-35.

[9] HM Galley Scourge Muster, 1779-1780, ADM 36/10427, TNA; HM Galley Arburthnot Muster, 1783, ADM 36/10426, TNA; Foy, “The Royal Navy’s Employment of Black Mariners and Maritime Workers, 1754-1783,” 24-25.

[10] Kevin Dawson, “Enslaved Ship Pilots in the Age of Revolutions: Challenging notions of race and slavery between the boundaries of land and sea,” Journal of Social History, 47, no. 1 (Fall 2013), 71-72; HM Galley Scourge Muster, 1779-1780, ADM 36/10427, TNA; John Gambier to Sir George Pocock, March 30, 1762, ADM 1/237, f. 51, TNA; Douglas Hamilton, “‘A most active, enterprising officer’: Captain John Perkins, the Royal Navy and the boundaries of slavery and liberty in the Caribbean,” Slavery & Abolition, (May 2017), 2; Foy, “The Royal Navy’s Employment of Black Mariners and Maritime Workers, 1754-1783,” 15-16.

[11] Jean Martielhe, The Huguenot Galley Slaves (New York, 1867), Chap. 6; London Evening Post, Oct. 7, 1741; Carla Rahn Phillips, “The Life Blood of the Navy’: Recruiting Sailors in Eighteenth Century Spain,” Mariner’s Mirror, 87 no. 4 (2001), 421; Mariana Candido, “Different Slave Journeys: Enslaved African Seamen on Board of Portuguese Ships, c. 1760 1820s,” Slavery & Abolition, 31, no. 3 (Sept. 2010), 399; N.A.M. Rodger, The Safeguard of the Sea: A Naval History of Britain, 660-1649 (New York: W. W. Norton, 1999).

[12] Charles R. Foy, “Seeking Freedom in the Atlantic World, 1713-1783,” Early American Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 4:1 (Spring 2006), 53, 60, 65; Philip D. Morgan, Slave Counterpoint: Black Culture in the Eighteenth-Century Chesapeake & Lowcountry (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998), 238.

[13] Virginia Gazette (Dixon & Nicolson), March 3, 1781.

[14] Denver Brunsman, “Men of War: British Sailors and the Impressment Paradox,” Journal of Early Modern History 14 (2014), 19.

[15] HM Galley Comet, Muster, 1780-81, ADM 36/10258, TNA; and HM Galley Vindictive, Muster, 1779, ADM 36/10429, TNA.

[16] HM Galley Arbuthnot, Muster, 1780-81, ADM 36/10213, TNA; HM Galley Clinton, Muster, 1779, ADM 36/9965, TNA; HM Galley Comet, Muster, 1780-81, ADM 36/10258, TNA; HM Galley Cornwallis, Muster, 1777-80, ADM 36/10259, TNA; HM Galley Delaware, Muster, 1777-79, ADM 36/10139, TNA; HM Galley Dependence, Muster, 1777-79, ADM 36/8508, TNA; HM Galley Hamond, Muster, 1780-82, ADM 36/9972, TNA; HM Galley Philadelphia, Muster, 1778-81, ADM 36/9932, TNA; HM Galley Scourge, Muster, 1779-80, ADM 36/10427, TNA; HM Galley Vaughan, Muster, 1779-81, ADM 36/10395, TNA; HM Galley Vindictive, Muster, 1779, ADM 36/10429, TNA; HM Galley Viper, Muster, 1780-83, ADM 36/10390, TNA; and HM Galley Vixen, Muster, 1779-83, ADM 36/10389, TNA.

[17] Brunsman, “Men of War: British Sailors and the Impressment Paradox,” 34.

[18] Daniel Vickers with Vince Walsh, Young Men and the Sea: Yankee Seafarers in the Age of Sail (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005), 119. See also Cheryl A. Fury, ed., The Social History of English Seamen, 1485-1649 (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2012), 269.

[19] HM Galley Arbuthnot, Muster, 1783-1786, 36/10426, TNA; HM Galley Adder, Muster, 1782, ADM 36/10384, TNA.

[20] Brunsman, Evil Necessity, 122; Bolster, Black Jacks, 30-323, 71-72; Charles R. Foy, “Eighteenth-Century Prize Negroes: From Britain to America,” Slavery and Abolition 31:3 (Sept. 2010): 381; Opinion of John Straker of the Vice-Admiralty Court, 1795, Papers of Adm. Sir Benjamin Caldwell, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, UK, CAL 127.

[21] Nicholas Rogers, The Press Gang: Naval Impressment and its opponents in Georgian Britain (New York: Continuum, 2007), 39.

[22] Leon Fink, Sweatshops at Sea: Merchant Seamen in the World’s First Globalized Industry (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011), 13.

[23] Benjamin Quarles, The Negro in the American Revolution (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996), 137; Michael Lee Lanning, African Americans in the Revolutionary War (New York: Citadel Press, 2005), 210.

[24] HM Galley Vindictive, Muster, 1779, ADM 36/10429, TNA; John Marrant, Narrative of the Lord’s Wonderful Dealings (London, 1785), 94. Historians dispute whether Marrant served in the Royal Navy. Vincent Carretta, “Black Seamen and Soldiers,” 18th Century Studies 36, No. 3 (Fall 2014), 1500-153. However, his characterization of how a free black might have felt about being impressed is still a useful tool in contextualizing the experiences of black seamen.

[25] Bruno Pappalardo, Royal Navy Lieutenant’s Passing Certificates, 1691-1902 (Kew, UK: List and Index Society, 2002). The vast majority of galley commanders on the North American coast did not pass the Lieutenant’s Exam, a clear indication that galley commanders, Brown and Smith, notwithstanding, were not the best of the navy’s officers.

[26] Charles R. Foy, “Possibilities & Limits for Freedom: Maritime Fugitives in British North America, ca. 1713-1783,” in Gender, Race, Ethnicity, and Power in Maritime America (Mystic, CT, 2008), 43-54.

[27] HM Galley Adder, Muster 1782, ADM 36/10384, TNA.

[28] HM Galley Scourge, Muster 1779-1780, ADM 36/10427, TNA; HM Galley Arbuthnot Muster, 1783-86, ADM 36/10426, TNA. The return of former slaves by navy officers was hardly limited to those serving on Royal Navy galleys. Foy, “The Royal Navy’s Employment of Black Mariners and Maritime Workers, 1754-1783,” 14.

[29] Enslavement of captured free black seamen was not uncommon in the eighteenth century. Foy, “Eighteenth-Century Prize Negroes,” 379-393.

One thought on “Compelled to Row: Blacks on Royal Navy Galleys During the American Revolution”

Thanks very much for this. I’m looking at the prospects of Black mariners after the war. This was very helpful.