The American Revolution was fought from Maine to Illinois, hundreds of military encounters occurring in what eventually became the United States of America. Among those events were two skirmishes on Prudence Island, a large island in Narragansett Bay in Rhode Island, on January 12 and January 13, 1776. Although small events that did not alter the course of the war, the battles showed the mettle of the Rhode Island Militia and challenged British strategy in the Rhode Island theatre of operations.

The smallest colony, Rhode Island, with a population of 60,000, quickly responded to the events of Lexington and Concord, sending a brigade of three regiments and some artillery under Nathanael Greene to Boston that were eventually incorporated into the Continental Line.[1] From the beginning of the war, however, Rhode Island’s leaders were worried about the unique geography and the problems it posed to defending such a vast amount of coastline:

Unfortunately for the inhabitants, this colony is scarcely any thing but a line of sea coast. From Providence to Point Judith; and from thence, to the Pawcatuck river is nearly eighty miles; on the east side of the bay, from Providence to Seaconnet Point, and including the east side of Seaconnet, until it meets the Massachusetts line is about fifty miles; besides which are the navigable rivers of Pawcatuck and Warren. On the west side of the colony doth not extend twenty miles; and on the east side, not more than eight miles from the sea coast above described. In the colony are also included several islands, all which are cultivated and fertile, and contribute largely to the public expense; the greater part of the above mentioned shores, are accessible to ships of war.[2]

Little did Rhode Island’s political leaders know, but their colony would soon become a battle ground, and the islands in the Narragansett Bay would play an important role in the Revolution.

With many of Rhode Island’s men serving in the army besieging the British in Boston, an active call out went out to the various militia companies throughout the state to begin garrisoning strategic points along Narragansett Bay. Tasked with erecting batteries and other fortifications, the militia also erected a series of alert beacons that could be seen for miles to alert other companies to respond. Volunteering for varying terms of service, the militia provided invaluable service monitoring Narragansett Bay to ensure that British raiding parties did not attack settlements along the shore. This service would continue throughout the Revolution.[3]

Among the many Rhode Islanders suddenly caught up in the Revolution was thirty-five year old Capt. Joseph Knight of Scituate. A well-off farmer who owned large tracts of land, Knight was also involved in the Hope Furnace Company, managed by the Brown family of Providence, that cast cannon for the Patriot cause. “He seems to have had a taste early for military life,” and received his first commission as an ensign in 1766. Knight had steadily risen in rank to captain in 1774, taking command of the First Company of the Third Battalion of the Providence County Regiment. Throughout the winter of 1774-1775, Knight, like many, knew that war was coming and trained his men frequently. Scituate, a large, rural farming town some distance from Narragansett Bay in western Rhode Island, was thoroughly on the side of the American rebels.

Upon hearing of the Lexington Alarm on April 19, 1775, Knight called his men together and mustered the following morning. With fifty-two men he began his march to Boston, among the first Rhode Islanders to answer the call. After crossing into Massachusetts, the Scituate company received word that the British had returned to Boston, and Knight and his men returned to Scituate. With the American Revolution now underway, Captain Knight left his five children and wife Elizabeth at home in Scituate and proceeded to Warwick Neck on the western shores of Narragansett Bay, just below Providence. Situated mid-way up the bay, the Neck would be garrisoned by Knight and his Scituate men for most of the Revolution.[4]

With the British garrison besieged in Boston by thousands of Americans under George Washington, supplies for the Crown forces became a focal point. Enjoying free access to the sea, without an effective American naval presence, Vice Admiral Richard Graves began to send ships of his fleet out of Boston to forage for supplies and raid coastal settlements. One squadron under Capt. James Wallace was dispatched to Narragansett Bay. Wallace, the commander of HMS Rose, had been in Rhode Island waters before, patrolling the entrance to Narragansett Bay since late 1774 to prevent smuggling operations.[5]

Captain Wallace became the scourge of Narragansett Bay as he kept most shipping in port, demanded supplies from Newport and neighboring communities, and threatened to bombard Newport if his demands were not met. Also operating in Narragansett Bay was HMS Glasgow and HMS Swan. While Newport, a Loyalist stronghold, provided Wallace with many supplies such as beef, rum, and dried peas that he sent on to Boston, there were not enough supplies to feed the British army there as well as to prevent the people of Newport from starving. With his supply line in Newport beginning to falter, Wallace began to look elsewhere in the bay for supplies. The Rhode Island General Assembly knew Wallace could strike anywhere along the shore and ordered out additional militia companies to guard the coast. Captain Wallace’s attention soon turned to another large island, further up the bay. Up to this point, Rhode Islanders had freely given in to Wallace’s demands for supplies. This time, they would respond with blood.[6]

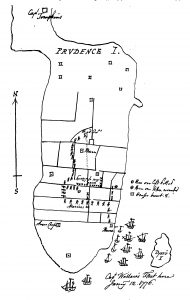

Situated at the midpoint of Narragansett Bay, Prudence Island is the bay’s third largest island. Part of the town of Portsmouth, Prudence is roughly six miles long, and one mile wide at it’s widest. The island is situated one and a half miles south of Bristol, and the same distance from Warwick Neck. A farming community, largely raising potatoes and sheep, Prudence was home to 33 families and 228 people according to the 1774 Rhode Island census. With Captain Wallace and his squadron a continued threat to the people of Rhode Island, the General Assembly, not wanting Wallace to gain more supplies, ordered all livestock that could be moved off of Prudence, Patience, and Conanicut Islands to be moved onto the mainland to prevent it from falling into British hands. Unlike the majority of Newport residents, the people of Prudence were eager to join the “patriotic opposition to that system of tyranny and despotism designed for enslaving the American colonies.” Likewise, the men of Prudence were “ready to contribute all reasonable assistance, towards prosecuting the present war, justly undertaken in defence of the United American colonies.”[7]

Wallace and his men had visited Prudence briefly twice previously, the first time on August 24, 1775. Landing about 100 men on the island, they “plundered” the farm of John Allin, seizing some twenty sheep, thirty turkeys, bushels of corn, as well as a ton of hay. The supplies were taken onboard HMS Swan and later sent to Boston. On November 17, 1775 Wallace’s men pillaged two houses, taking, among other items, numerous articles of clothing, kettles, geese, and for unknown reasons “one large mahogany desk.” While largely unopposed previously, Rhode Island had begun sending privateers out of Providence with an aim to attacking British shipping; occasionally these ships engaged in long range cannon duels with Wallace, with little damage to either side. For the most part, Wallace’s mission in Narragansett Bay was largely successful. He purchased the majority of his supplies, resorting to raiding only when necessary.

Throughout 1775, these raids had largely been bloodless; several men were wounded on a raid near Stonington, Connecticut, while on December 10, 1775 a party of British Marines engaged in a brief skirmish on Conanicut Island, opposite Newport. The Rhode Island militiamen “had been enlisted but a few days, and arrived there but the evening before, in miserable condition.” Despite the harsh New England winter weather, the militia stood up to the Marines in a brief skirmish, wounding nine of Wallace’s men for one American casualty. Captain Wallace did not learn from these events and instead decided to launch another raid on Prudence Island.[8]

Although he had been stripped of power by the General Assembly, Gov. Joseph Wanton, a fervent Loyalist, continued to officially serve as the governor of Rhode Island, although he was soon to be deposed and replaced by Nicholas Cooke. On January 11, 1776, Wanton sent a letter to Capt. Samuel Pearce, the commander of the Second Portsmouth Company composed of men from Prudence Island, that Captain Wallace would stop at Prudence on January 12 to purchase supplies. Wanton advised Pearce to comply with Wallace’s demands and sell whatever livestock and provisions that remained on the island. The governor’s letter sent Pearce into a rage. He immediately sent a reply letter back to Newport, telling Wanton “that whatever Wallace took off this island, would be taken off at the point of the bayonet.” The die was now cast.[9]

It was clear to the inhabitants of Prudence that their island would soon become a battle ground. As the captain of the local militia company, Pearce ordered all women and children off the island. Bidding farewell to their wives and children, many of Pearce’s men gave up their blankets to protect them from the winter cold as they rowed away to the safety of Bristol and Warwick. Taking with them many household valuables and much of the livestock that remained, it was a tearful scene, as the women realized that their husbands, fathers, brothers, and sons were about to engage in battle. Described as a “bitter cold winter day,” January 11, 1776 would be the last time that many would ever set foot on Prudence, settling instead on the mainland of Rhode Island.[10]

With the women and children off the island, all that remained were the men of Captain Pearce’s Second Company composed of thirty-two men, among them eleven African-American slaves who had been given weapons and instruction on how to use them. As was typical of a small island community, most of these men were related to each other; indeed, half of Pearce’s company was composed of men from the Allin family. Dressed in their working clothes and armed with a variety of firearms, these citizen-soldiers prepared to fight to the most powerful nation on earth. Few had cartridge boxes, even fewer had bayonets. Captain Pearce knew that his thirty-two men could not make a determined stand against the British. Not knowing when or where the British would land, Pearce sent off hasty dispatches to Bristol and Warwick pleading for reinforcements.[11]

Col. John Waterman commanded at Warwick Neck. His forces were comprised of several militia companies from neighboring towns, manning an earthwork containing two eighteen pound cannon. Brig. Gen. William West, commander of the Providence County Brigade, was the overall commander of Patriot forces on the shores of Narragansett Bay and commanded from a post in Newport. In the early morning hours of January 12, 1776, General West sent out orders to a trusted subordinate, Captain Knight, to take ten of his men and report immediately to Prudence on “fatigue duty.” From their vantage point on Warwick Neck, Knight and his men had seen Wallace sailing along Narragansett Bay. It was clear to Knight and his twelve men as they boarded the scow to take them the short distance across the bay that, with the civilians now off Prudence, a fight was about to ensue.[12]

Also dispatched from Waterman’s command was the Kentish Guards. A pre-war “independent company,” composed of many of the elite from the West Bay towns of Coventry, Warwick, and East Greenwich, among the members previously carried on the rolls was Nathanael Greene, James Mitchell Varnum, and Christopher Greene, now all serving in high office in the Continental Line. A cradle of colonial leadership, the Kentish Guards provided many of the officers who served in Rhode Island’s Continental regiments. With new recruits and men who remained behind in East Greenwich, the Kentish Guards erected a fort to defend their town and like many of their neighbors spent their days manning it. The Guards would not make it into the fighting on January 12.[13]

From Bristol, Col. William Richmond dispatched Ens. James Miller with a few men from Richmond’s State Regiment. This was a large regiment of twelve companies that had been raised in November 1775 for full time state service to serve for one year. While the terms of service of the militia varied from several days to a few months, the men of Richmond’s Regiment and their brothers in Lippitt’s Regiment were constantly on watch duty on the eastern shores of Narragansett Bay where most of the population and trade of Rhode Island occurred.[14]

At four o’clock in the afternoon of Friday, January 12, 1776 Captain Wallace anchored a half-mile off the south-east tip of Prudence Island, immediately opposite Dyer Island. Wallace landed about 250 British Marines and sailors on Prudence. The weather was freezing, daylight was fading, and there was a large amount of snow on the ground. Instantly, Wallace ordered six houses near his landing point put to the torch. Dr. Ezra Stiles, a Congregational minister and the librarian at the Redwood Library in Newport, wrote, “I saw the flames from the Top of my house due North. He [Wallace] is now inhumanly spreading Barbarity, Desolation & Revenge there.” As Stiles watched the flames on Prudence, he saw Patriot militia companies from Newport muster in the town and advance to garrison the fortifications around the harbor.[15]

At four o’clock in the afternoon of Friday, January 12, 1776 Captain Wallace anchored a half-mile off the south-east tip of Prudence Island, immediately opposite Dyer Island. Wallace landed about 250 British Marines and sailors on Prudence. The weather was freezing, daylight was fading, and there was a large amount of snow on the ground. Instantly, Wallace ordered six houses near his landing point put to the torch. Dr. Ezra Stiles, a Congregational minister and the librarian at the Redwood Library in Newport, wrote, “I saw the flames from the Top of my house due North. He [Wallace] is now inhumanly spreading Barbarity, Desolation & Revenge there.” As Stiles watched the flames on Prudence, he saw Patriot militia companies from Newport muster in the town and advance to garrison the fortifications around the harbor.[15]

The small force of militia and state troops, some fifty men all under the command of Captain Pearce, moved up to engage the enemy. Ensign Miller ordered some men to set fire to a large quantity of hay that he believed the British wanted to capture. Although out of range, Pearce ordered his men to open fire. The American volley provoked a return in which a Private Williams of Richmond’s Regiment was “shot through the breast, the ball passing directly under the breast bone, went in one side and came out the other.” Williams was left where he fell and taken prisoner by the British; he was later released. The Americans returned fire “with much spirit.”

It soon became clear to Knight and Pearce that the British force was much larger than they had expected. In the fighting one of Pearce’s men went down instantly killed. After firing three volleys at the British, and determined to live to fight another day, the two captains ordered their men to retreat, and they engaged in a running gun battle with the British up the island. In his official report, Captain Wallace wrote, “We landed beat them from fence to fence, for four miles into their country, firing and wasting the country as we advanced.” In this engagement, another Prudence Island soldier was lost, captured by the British. Crown forces finally gained the upper hand and surrounded the Americans on three sides as they were pushed to the northern tip of Prudence. Finally, with night falling, the Scituate and Portsmouth men, together with Ensign Miller “were obliged to make a precipitate retreat, and were taken off by their boats to Warwick Neck, the only thing which could have prevented their being hemmed in and cut to pieces.” Captain Wallace acknowledged the loss of three men “slightly wounded.” [16]

With American forces off the island, the British commenced burning homes, barns, and other structures. The blaze lit up the night sky, being seen “for many a mile around.” In Newport fear abounded that Wallace would return to destroy the town. Dr. Stiles called it, “A melancholly destressing prospect!” At 8:00 that night, “the People were fatigued with Cold, and fearing they might be Frost Bit.” Wallace ordered his men back to their ships for the night. Many local militiamen saw the fire and flocked to Warwick Neck and Bristol, eager to exact revenge against the British. Unfortunately there were few boats available to transport men to the island. As night combat was all but unknown in the eighteenth century, General West ordered his men to wait until morning to cross and engage the British again.[17]

After missing the fighting on January 12, Col. Richard Fry, in the tradition of the New England Militia, “proposed” to his men that they row out to Prudence and “prevent their landing.” Fry’s proposal was accepted, and a party of some eighty men from the Kentish Guards rowed the six miles from East Greenwich to Prudence. Fry’s men landed early in the morning and immediately began cooking breakfast at their camp on the northern tip of the island. Pvt. Wanton Casey, only fifteen and a member of the Guards, recalled, “While eating breakfast, we received news by a man who ran very fast, that the enemy were landing three or four miles below us. Our resource was to brave the danger as well as we could.” Fry immediately ordered his men into line and with “drums beating and colors flying,” marched to engage the British.[18]

Responding to the alarm from General West, fifty men rowed to Prudence from Warren, while a force of eighty men in whaleboats landed at day break on the island. The main force of men from Bristol was led by Capt. William Barton of Richmond’s Regiment, a pre-war hatter from Warren who had seen service at Bunker Hill and worked his way to company command. After the burning the night before, the British had returned to their ships. At nine o’clock on the morning of January 13, they returned to continue foraging for supplies and to continue the destruction of the island. From his post on HMS Rose, Captain Wallace observed “large bodies of armed Rebels stood behind stone fences to oppose us.”[19]

Among those who returned to the fighting on January 13 were Ensign Miller and his men from Richmond’s Regiment. Due to a lack of boats at Warwick Neck, few men responded from Colonel Waterman’s forces. Perhaps because Wallace’s ultimate intentions were unknown, the majority of Rhode Island forces remained on the mainland, ready to defend Providence, which was believed to be Wallace’s next objective. Captain Barton deployed his men and waited for the British approach. A British patrol that “strayed too far from the Main Body, fell into an Ambush,” as the Marines and sailors attacked a picket post manned by Lt. John Carr. Soon a “smart engagement ensued” that resulted in the deaths of three British.[20]

The fighting raged for nearly three hours on Prudence as Captain Barton led the American forces near Farnham’s Farm. Capt. Tyringham Howe, the master of HMS Glasgow, “Observ’d an irregular fire between the Rebels & our people.” The Providence Gazette reported, “The enemy several times sent out flanking parties, which were as often drove back to their main body.” In the fighting, Capt. Billings Throop, commanding a company in Richmond’s Regiment, was mortally wounded; he died on January 25, 1776. Another of Billings’s men, Pvt. Job Greenman, took a bullet to the left leg. In all, Barton lost one officer and one private mortally wounded, three men wounded, and one man captured. Although outnumbered, these Americans were literally fighting on their own soil and put up a vigorous effort to drive the British back to their ships. From Newport, Dr. Stiles heard “fireing all the afternoon.” After talking to several Newport men who were in the engagement, he wrote in his diary. “Our men fought bravely, repulsed & routed the whole Body tho’ they had nearly surrounded them on each flank.”

After three hours of heavy skirmishing, British forces retreated back to their ships. After the fighting, the Rhode Islanders discovered two British Marines dead on the field, and another wounded who was taken prisoner; “they likewise carried off a number of killed and wounded, particularly an officer, that appeared to be badly wounded.” The Providence Gazette reported, “Our officers and men behaved with the greatest gallantry, and had there been boats at Warwick to carry over the reinforcements from thence, it is thought the enemy’s whole party would have been killed or taken.”[21]

Ens. James Miller, who had been in the action both days, recalled nearly sixty years later, “It was never ascertained how many were killed or wounded, but from the traces of blood it was supposed the enemy suffered some loss in their retreat, pursued as they were by an incessant fire to their ships.” Besides losing several men, all that Wallace’s squadron found on Prudence were 100 sheep and several bushels of potatoes. After the battle, from his headquarters in Newport, General West received intelligence from a man named Slocum who was released by the British that “Capt Wallace is very sick of his Voyage to Prudence, having lost fourteen Men kill’d & a number Wounded – They Buried Several on Hope Island. I’m informed Nine were found buried there in one Grave. Two of the wounded are since dead & buried on Rose Island.” Captain Wallace, the Royal Navy, and British Marines paid a heavy price for their expedition to Prudence Island. As is typical of many Revolutionary War engagements, the total number of casualties sustained by both sides will never fully be known. Wallace wrote, “Our loss would have been less, had our people have had less spirit.”[22]

On January 15, the British returned to Prudence. In the two days since the action of January 13, Wallace anchored off Hope Island where he obtained wood and other supplies. On the fifteenth, Wallace completed his destruction of the island, burning a windmill, six houses, and a number of out buildings. Despite having a large presence in the area, no Rhode Island Militia troops rowed out to the island to engage Wallace. For the rest of the Revolution, Prudence would remain a deserted island. After the occupation of Newport in December 1776, occasional British parties would visit the island to forage for supplies. On December 4, 1777 another skirmish on the island resulted in the deaths of three British Marines.[23]

Even after receiving a blooding at Prudence Island, Wallace remained in Narragansett Bay for several days. He continued to press for supplies, which were given by Loyalists in the town. After receiving news of the American defeat at Quebec, a number of “Friends to the Ministerial Forces in Newport, appear more open & Bold than heretofore, by endeavoring to inflame the Minds of the Inhabitants of the Town.” General West did his best to stamp out these Loyalist feelings as he tried to persuade the General Assembly to let him remove “Obnoxious Inhabitants” from the island. West complained, “Those persons give us more Trouble than Wallaces whole Fleet & as much Danger is to be expected of them.” Eventually a number of Loyalists were removed from Newport and sent to Glocester in rural western Rhode Island under General West’s personal observation.[24]

After having his forces bloodied at Prudence, and with the siege of Boston continuing, Wallace’s squadron was recalled to Boston for refitting and eventual service elsewhere in the American theatre. For nearly two years, Captain Wallace had “kept the Inhabitants of that Province in so much Awe.” He had performed valuable service gathering supplies largely from the populace of Newport loyal to the British cause, while attempting to keep Narragansett Bay closed to American privateers. When he decided to attempt to gather supplies from Prudence, however, Wallace and his men ran headlong into a determined band of Rhode Island Militia who would not give in to his demands. Adm. Molyneux Shuldham praised his subordinate’s service in Rhode Island. “Captain Wallace’s services deserve every reward can be confer’d on him, I humbly recommend sending him out in a Larger and better ship.”[25]

Capt. James Wallace utterly destroyed Prudence Island. Once a vibrant farming community, his forces “agriculturally left the island a wreck.” Nearly every dwelling on the island was destroyed, with only “a mass of blackened ruins” remaining, while all the livestock had either been carried off or taken by the British. Many families never returned to the island. The Rhode Island General Assembly heard the pleas of the islanders and repaid twenty families for the loss of crops and livestock, as well as home goods such as tools and other items taken by the British. In addition, claims were filed for the homes destroyed on the island. While this money repaid them for some of the items lost during the burning, it was little compensation for the lives shattered by the destruction of the island. It was only by 1870 as Prudence Island developed into a popular summer retreat that the island regained the population lost during the Revolution.[26]

The Battle of Prudence Island had a profound impact on the lives of the participants. Capt. William Barton was promoted to major for his actions on January 13. On July 10, 1777 he again distinguished himself leading a raid in Newport that resulted in the capture of British commander Gen. Richard Prescott. Severely wounded in a skirmish in Bristol in 1778, he would end the war as a colonel. The town of Barton, Vermont was named in his honor.[27]

Captain Knight was also promoted to major for his actions at Prudence Island. He remained in the field throughout the Revolution and saw service at the Battle of Rhode Island in 1778. He attained command of the Third Providence County Regiment and later was actively involved in town politics, serving many years on the town council, while also running a tavern. When Lt. Col. Knight died in 1825 at the age of eighty-five, he was still remembered as “Scituate’s bravest son.”[28]

The two engagements on Prudence Island on January 12 and January 13, 1776 were decisive for the Patriot cause. Although the British would invade Newport in December 1776 and remained for three years, they were never able to use it as a base to conduct further raids into the interior of New England. The engagement at Prudence gave the British knowledge of the fighting prowess of the Rhode Island Militia, proving that they would violently defend their state against incursions. The few times that British forces did leave Rhode Island, for raids on Bristol, Warren, and elsewhere, militia forces always turned out in force, with little damage done by Crown troops. Furthermore, the British were never fully able to seal off Narragansett Bay to American privateers who used Providence as a base throughout the war.

For the Rhode Island Militia, Prudence Island was the first engagement for many of these men. For the remainder of the Revolution, they would remain constantly on alert, guarding the shores of Narragansett Bay. Thousands of militiamen responded and some were engaged in the Battle of Rhode Island on August 29, 1778. Furthermore, the events at Prudence showed the value of the alarm and beacon system that was common throughout much of New England that led to the overwhelming militia response. Although Prudence Island was thoroughly ravaged by the war, displacing many families and leaving the island a shell of its former self, the men of the Rhode Island Militia were able to give the British yet another defeat on the long road to independence.[29]

[1] Anthony Walker, So Few the Brave: Rhode Island Continentals, 1775-1783 (Newport: Seafield Press, 1981), 1-5.

[2] John Russell Bartlett, ed. Records of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations: Volume VII (Providence: A. Crawford Greene, 1862), 424-426.

[3] For the most comprehensive view of this service refer to Edward Field, Revolutionary Defenses in Rhode Island (Providence: Preston and Rounds, 1896).

[4] C. C. Beaman, An History Address, delivered in Scituate, R.I. July 4, 1876 (Phenix, RI: Capron and Campbell, 1877), 41-43. John Russell Bartlett, Census of the Inhabitants of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, 1774 (Providence: Knowles, Anthony, & Co., 1858), 120. Joel A. Cohen, “Lexington and Concord: Rhode Island Reacts,” Rhode Island History, Vol. 26, No. 4 (October 1967), 97-102. Joseph Knight Papers, Robert Grandchamp collection.

[5] W.G. Roelker, “The Patrol of Narragansett Bay (1774-76) by H.M.S. Rose, Captain James Wallace,” Rhode Island History, Vol. 7, No. 1 (January 1948), 12-19.

[6] Roelker, “The Patrol of Narragansett Bay,” 11-22. William Bell Clark, ed. Naval Documents of the American Revolution: Volume 4 (Washington, D.C.: United States Navy, 1969), 48-51.

[7] Charles G. Maytum, “Early Prudence Island,” 2: 68-73, typescript at East Greenwich Public Library, East Greenwich, Rhode Island. Roelker, “The Patrol of Narragansett Bay,” 52-58.

[8] Maytum, “Early Prudence,” 72. Roelker, “Patrol of Narragansett Bay,” 52-53. James Wallace to “Inhabitants of Newport,” January 19, 1776, Rhode Island State Archives, Providence, Rhode Island. Newport Mercury, November 27, 1775.

[9] Cohen, “Lexington and Concord: Rhode Island Responds,” 101-102. Maytum, “Early Prudence,” 76-77.

[10] Maytum, “Early Prudence,” 73-77. Ezra Stiles, The Literary Diary of Ezra Stiles: Volume I, January 1, 1769-March 13, 1776, Franklin James Dexter, ed. (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1901), 653.

[11] Maytum, “Prudence Island,” 77. Field, Revolutionary Defenses, 24-26. Beaman, Scituate, 45.

[12] Field, Revolutionary Defenses, 82-84. Beaman, Scituate, 42. William West to Newport Town Council, January 30, 1776, Rhode Island State Archives. Rhode Island Militia Pay Receipts, Rhode Island State Archives.

[13] Daniel H. Greene, History of the Town of East Greenwich and Adjacent Territory from 1677 to 1877 (Providence: J.A. & R.A. Reid, 1877), 181-184.

[14] Walker, So Few the Brave, 11-22: 122-123. Catherine Williams, Biography of Revolutionary Heroes (Providence: The Author, 1839), 303-305.

[15] Stiles, Literary Diary, 653-654. William Bell Clark, ed. Naval Documents of the American Revolution: Volume 3 (Washington, D.C.: United States Navy, 1969), 800-801.

[16] Clark, Naval Documents: Volume 3, 767-768: 784. Providence Gazette, January 20, 1776. Maytum, “Early Prudence,” 79-81. Beaman, Scituate, 42. Williams, Biography of Revolutionary Heroes, 30-32: 303-305.

[17] Clark, Naval Documents: Volume 3, 784-785. Williams, Biography of Revolutionary Heroes, 303-305. Stiles, Literary Journal, 654. Providence Gazette, January 20, 1776.

[18] Greene, East Greenwich, 183-184.

[19] Williams, Biography of Revolutionary Heroes, 1-32. Field, Revolutionary Defenses, 16-18. Clark, Naval Documents: Volume 3, 784-785.

[20] Ibid. Providence Gazette, January 20, 1776. Field, Revolutionary Defenses, 60-63. Williams, Biography of Revolutionary Heroes, 30-32: 303-305. Walker, So Few the Brave, 11-22: 122-123.

[21] Stiles, Literary Journal, 654-657. Providence Gazette, January 20, 1776. Williams, Biography of Revolutionary Heroes, 30-32: 303-305.

[22] Williams, Biography of Revolutionary Heroes, 303-305. Providence Gazette, January 20, 1776. Clark, Naval Documents: Volume 3, 767-768: 954-955.

[23] Maytum, “Early Prudence,” 79-80.

[24] Clark, Naval Documents: Volume 3, 954-955. Sidney S. Rider, ed. The Diary of Thomas Vernon: A Loyalist, Banished from Newport by the Rhode Island General Assembly in 1776 (Providence: S.S. Rider, 1881), 1-18.

[25] Roelker, “Patrol of Narragansett Bay,” 56-58.

[26] Maytum, “Early Prudence,” 83-85. Revolutionary War Claims, Prudence Island, Rhode Island State Archives.

[27] William West to Rhode Island General Assembly, January 28, 1776, Rhode Island State Archives. For the best sketch on the life of Colonel Barton, refer to Christian M. McBurney, Kidnapping the Enemy: The Special Operations to Capture Generals Charles Lee & Richard Prescott (Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2014).

[28] Beaman, Scituate, 41-45. Providence Gazette, March 9, 1825.

[29] While many books have been written on Rhode Island’s role in the American Revolution, the most pertinent for this study in Christian M. McBurney, The Rhode Island Campaign (Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2011). For an excellent British perspective of operations in Rhode Island refer to Frederick Mackenzie, The Diary of Frederick Mackenzie (New York: New York Times, 1968).

One thought on “From Fence to Fence: The Battles of Prudence Island”

Robert: Congratulations on your fine essay on the Battles of Prudence Island. As I read it I found myself reflecting on the strong feelings of nationhood that began to develop during the Revolution. My distant grandfather, Sgt. Simon Giffin of Connecticut fought with Rhode Islanders (plus soldiers from MA, NJ, NH, VA, Oneida, and many others) during the War. He learned the geography of Narraganset Bay in 1778, surviving the hurricane of August 12-13, 1778 and the fighting before Newport and on Turkey Hill. After six years of witnessing the suffering and commitment of Rhode Islanders and so many others he came home a changed man, an American. My best, Phil Giffin