A single day of gory trauma defined the life of Brook Watson. As a teenager, he had gone swimming in Havana harbor, where a shark attacked him. The shark first peeled off the skin of his calf with its thrashing bite. With its second turn, Watson’s foot was wrenched away at the ankle. His own blood swirling around him, Watson must have contemplated his impending death. At the final moment, a boatload of sailors rowed to his rescue. They fended off the beast with a boathook and hoisted the critically injured boy aboard.[1] Watson suffered an amputation and spent the rest of his life on a wooden leg.

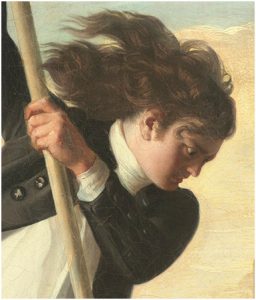

This event so affected Watson that he later incorporated his lost leg, complete with torn flesh at the top, in his coat of arms.[2] In 1777, Watson commissioned the artist John Singleton Copley to commemorate the event on canvas. Copley’s towering painting proved to be his most enduring masterpiece. Watson, naked and bleeding, reaches up from the water toward the outstretched hands of sailors. Rounding the stern, the shark opens its maw for a final, fatal bite. A single sailor, his foot on the bow, holds a boathook like a spear to deliver a blow of his own that would smite the creature.

It is a moving image even to modern eyes. When it was displayed in the Royal Academy in 1778, it carried an even greater weight. The American Revolutionary War was raging, and had taken a turn that distressed the once confident British empire. Burgoyne had been defeated at Saratoga with the shocking loss of his entire army. The French had just signed a treaty with the Americans, ensuring that the arch-rival of the British would mobilize on the continent and afloat.

In this atmosphere of national distress, Copley gave his London audience what they needed: heroes at a supernatural level. With Watson and the Shark, at one of the most troubling stages of the American Revolutionary War, John Singleton Copley elevated the image of the common sailor from mere participant in history to active savior of the British nation as embodied by Brook Watson.

With Watson and the Shark, Copley was tapping into a new trend in historical art. In 1770, this trend began with Benjamin West’s Death of General Wolfe. Rather than depict an event of a bygone era, West chose to represent an event in living memory. General Wolfe died from wounds sustained at the Plains of Abraham in 1759, just when he defeated the Marquis de Montcalm and secured Canada for the British empire. Only a decade had passed since the event. With the obvious exception of Wolfe, nearly all the figures depicted were still living. West also chose to clothe the figures in the uniforms and clothing of the day, not classical garb. As Dr. Bryan Zygmont writes, “West reinterprets the rules of what a history painting could be—both in regard to period depicted and the attire the figures wore—and at the same time followed a visual language that would have been familiar to its eighteenth-century audience. This composition set the stage for the many ‘contemporary’ history paintings that John Singleton Copley and John Trumbull painted throughout the rest of the eighteenth century.”[3]

Copley himself was impressed with The Death of General Wolfe, proclaiming it “sufficient of itself to Immortalize the Author of it.”[4] West’s use of classical composition and posture in a contemporary setting and with contemporary costume undoubtedly influenced Copley’s later Watson and the Shark.

Copley was adopting a new trend, and he was innovating. Benjamin West, in The Death of General Wolfe, relied on officers and gentlemen, with a sprinkling of common men here and there. The central and most important characters were men of social standing and power. A few sailors can be seen over the shoulders and between the central figures, indistinct by comparison. They give depth to the piece and add motion to the background, but this role is in service to the foreground and not important on its own. Until Copley’s Watson and the Shark, contemporary historical works were confined to the upper classes, with the more common people merely adding flavor or serving to balance a composition.

Even most marine art, a tradition that was a century old in Britain by the time of Copley and focused exclusively on the profession of common sailors, was confined to seascapes and harbor scenes often with ships at such a distance that if the artist chose to include sailors at all they were confined to specks in the rigging or on deck. By way of example, John Cleveley the Elder, a shipwright and carpenter by trade who turned to marine art, was exceptional in his willingness to populate his scenes with common people.[5] Even so, they were minute on the scale of three decker men of war.

The exclusion of common sailors from high art is not surprising. Jack Tar, as sailors were known, occupied a relatively low position in the social hierarchy in the British Atlantic world. The eighteenth-century wit Edward Ward, in his book The Wooden World Dissected, defined a ship as “old Nick’s academy, where the seven liberal sciences of Swearing, Drinking, Thieving, Whoreing, Killing, Cozening and Back-biting, are taught to full perfection.”[6] When the Hessian Private Johann Conrad Döhla crossed the Atlantic in 1777 aboard a British transport, he wrote that “the seamen are a thieving happy, whoring, drunken lot and much inclined to swearing and cursing people. They can hardly say three words without their curses ‘God damn my soul, God damn me.’”[7] These are behaviors that would be abhorrent in the upper classes, and only tolerated because of sailors’ position further down the social ladder. Sailors were all well and good aboard a ship and serving their purpose, but had no place being lionized on canvas.

Given the relative exclusion of common sailors from high art, what motivated John Singleton Copley to elevate them to such a prominent position in Watson and the Shark?

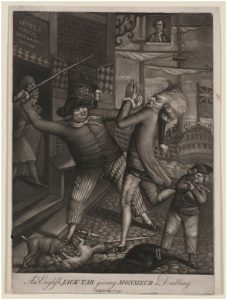

There was a trend in which sailors filled a central role that was unacknowledged in the world of high art, but ever-present in eighteenth century Britain: that of caricature. Increasingly throughout the century, and particularly with the American Revolutionary War, the character of Jack Tar took on the role of personifying the nation. There exists an entire tradition in caricature of Jack Tar fighting caricatures of France, Spain, the Netherlands, and America. Punching, whipping, and staring down the enemies of the nation, the common British sailor occupied the role of the empire itself: manful, violent, and strong.[8]

The caricature tradition of making Jack Tar a central figure in place of the nation was an understandable one. By the time Copley began work on Watson and the Shark, the Royal Navy had secured its place as protector of the nation. Common sailors had proven themselves adept mariners and strong fighters. They were celebrated in song with the rousing Heart of Oak.[9] Working the guns and sails of their massive warships, common sailors ensured victory in the Seven Years War, and were in large part responsible for the Annus Mirabilis of 1759, the “year of miracles,” when the Royal Navy broke the back of the French at the Battles of Lagos and Quiberon Bay. The navy served as savior of the nation, and the navy was composed of laboring class men.

The joy felt in the wake of 1759 had more than dissipated by 1778. General Burgoyne suffered a shocking defeat at Saratoga late in the previous year, and two months before Watson and the Shark was exhibited at the Royal Academy, the French signed an alliance with the United States. French involvement widened the war from a distant colonial rebellion to a very real threat of local invasion. This feeling of vulnerability was coincidentally underlined within the week that Watson and the Shark went on display at the Royal Academy.[10] John Paul Jones, commanding the Ranger, landed sailors in a raid at Whitehaven. Though largely unsuccessful, the Ranger’s action proved that the English coast could be invaded. Indeed, it could be invaded by a relatively inept provincial force that was decidedly less skilled than the British navy, ill-equipped, and borderline mutinous. What would happen when the much more adept French navy took to sea?[11]

Living in London but born in Boston, Copley was in an awkward position. “I am desireous of avoideing every imputation of party spir[it],” Copley wrote in 1770 from Boston, “Political contests being neighther pleasing to an artist or advantageous to the Art itself.”[12] Despite this avowal of neutrality, it would have been difficult for Copley to maintain that middle of the road spirit as an American in London at the height of the violent rebellion. At that, it is unlikely that Brook Watson would have commissioned him for a strictly factual and unadorned interpretation of his childhood trauma.

Briefly held by Brook Watson after the siege of Montreal in 1775, the American officer Ethan Allen decried “Brook Watson: a man of malicious and cruel disposition, and who was probably excited, in the exercise of his malevolence, by a junto of tories, who sailed with him to England” and accused him of “a conduct so derogatory to every sentiment of honor and humanity.”[13] A later American critic decried Copley’s working with Watson, who he decried as memorable as “arrayed with our enemies in opposition to our independence.”[14]

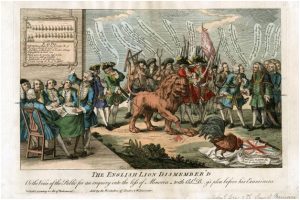

Paid by a well-known and vociferous Tory politician, and painting in the heart of an empire in turmoil, Copley addressed the national trauma by way of Watson’s personal trauma. Watson’s lost leg provided a perfect metaphor for the nation on the verge of a great loss. Again, there is precedent in caricature. When Admiral Byng abandoned Minorca to the French at the outset of the Seven Years War, an anonymous caricature artist commemorated the loss with The English Lion Dismember’d. The image of the English lion losing its paw is repeated in Thomas Colley’s 1780 print, also entitled The English Lion Dismembered, though recast as the loss of the American colonies rather than the island of Minorca.[15] A more directly parallel metaphor was already apparent in caricature. A Dutch artist depicted Britannia herself made a quadriplegic with each severed limb marked for a North American colony or city.[16] About the same time, an English artist used the exact same image of Britannia dismembered.[17]

Copley made Watson the stand-in for Britain. His bleeding stump represents the loss the empire was about to suffer. Such a loss was devastating to be sure, but the shark was still bearing down on Watson. France and her navy were a narrow channel away from the English, and could possibly maul them. Watson is naked and vulnerable, barely keeping his head above water.

Notably, Copley has placed Watson in opposition to the common sailor. Where Watson, representing to some degree the ruling class and gentry, is helpless, the sailors are powerful. They are placed both literally and figuratively above Watson in their boat. They are clothed and strong. It is these men who will save Britain.

The posture of the figures underlines their almost metaphysical importance. Though common men, the sailors are given poses inspired by religious works. The sailor in the bow, with his boathook and flowing hair, is intentionally modeled after St. Michael, the archangel most often depicted as thrusting a spear into a demon underfoot. The two mariners reaching for Watson’s outstretched hand are based on the Renaissance artist Raphael’s Miraculous Draught of Fishes. Where the sailors are inspired by Christian tradition, Watson is depicted in a pagan one. His body is contorted after the marble Borghese Gladiator, and his face may well be based on one of the figures being ensnared by a monstrous snake in the sculpture Laocoön.[18] The use of mythological and religious imagery in a secular context is significant enough, but Copley split his painting along a line between the righteous Christian-inspired sailors, the pagan-inspired Watson below, and the demonic fish.

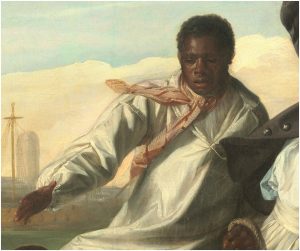

Clothed in common sailors’ slop clothes and surprisingly diverse in age and origin, Copley emphasizes the meanness of Britain’s saviors. An early study composed by Copley in preparation for Watson and the Shark shows little change in their posture, but their appearance varies dramatically. In one study at the Detroit Institute of Art, Copley’s figures were all young and white. The sailor in the bow lacked his petticoat trousers and wore only breeches. While breeches were worn by all classes of society, petticoat trousers were almost unique to common sailors, and certainly unheard of higher in the social hierarchy. Another sailor is aged, heavier set, and given a receding hairline. Still another, in fact the apex figure of the piece, is of African descent in the finished painting.[19]

By changing his boat crew from younger, exclusively white men to a more diverse set of sailors, Copley was better representing the actual makeup of Britain’s maritime manpower. Placing the black man at the top of the piece was a radical stroke. While this figure occupied the physical peak of Copley’s composition, his person was relegated to the nadir of British social hierarchy. The inversion of rank is figuratively and literally central to Watson and the Shark. These men would not prevent the loss of the colonies, but they would slay their enemies afloat and save the nation from a more severe fate. Further, the sailors would save them by force.

The sailor in the bow, that powerful looking man in the posture of a saint, bears a face inspired by the seventeenth century artist Charles Le Brun’s 1698 book Conférence de M. Le Brun sur l’expression générale et particulière: a collection of facial expressions intended to help artists convey specific emotions. The specific emotion chosen for the sailor in the bow is Figure 9, Le Mépris, “the contempt.”[20] Thrusting his boathook as a lance only demonstrates the method by which the sailors will defeat Britain’s enemies. It is the look of contempt on the face of this sailor that reveals how they feel about their foes.

Copley’s sailors represent an idealized, borderline supernatural laboring class that will rescue the nation from their moment of peril in a departure from the tradition of contemporary historical works. Watson and the Shark was roundly praised when it was exhibited at the Royal Academy. “John Singleton Copley,” wrote the critic of the General Advertiser and Morning Intelligencer, “deserved particularly to be praised.”[21] Another writing for the Public Advertiser proclaimed “Mr. Copley has succeeded beyond the most sanguine Expectations: this picture is extremely well conceived in all its parts, and appears to be the Result of mature Reflection. In short, it is a perfect picture of its kind.”[22] It was the beginning of trend that would enshrine sailors as national paragons for generations to come.

In the wake of the American Revolution, the artist James Northcote painted a similar epic historical painting (now lost) that also placed sailors at the forefront and cast them as saviors. The Sinking of the Centaur, exhibited in 1784, was heralded by its author as “the grandest and most original thing I ever did.”[23]

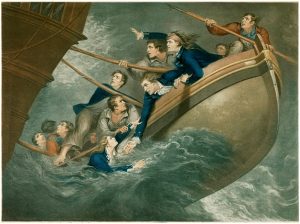

Inherently political, Northcote’s piece depicts the escape of sailors and officers from the sinking 74-gun ship of the line Centaur, lost in a hurricane in 1782. It had been escorting a huge convoy, and accompanying ships seized from the French at the victorious Battle of the Saintes. Cap. John Inglefield later wrote the wind was “exceeding in violence every thing of the kind I had ever seen, or had any conception of.” The crew of the Centaur, excepting the men in this boat alone, were among thousands who drowned in the Atlantic tempest.[24]

The hurricane of 1782 spoiled England’s single great naval victory of the Revolutionary War. Northcote’s sailors still wield boathooks, but only to extricate themselves from the sinking vessel. The Centaur slipping under the waves stands in for the lost American colonies, threatening to drag the empire down with them. Another boy is in the water, this one a Midshipman Baylis, but his distress is eclipsed by that of the men. Their eyes are not turned to Baylis, they are fixed on the Centaur. The disastrous sinking, as with the disastrous loss of America, is more important than the immediate state of a gentleman.

Northcote may have called the Sinking of the Centaur “original,” but the inspiration of Watson and the Shark is obvious in both its composition and meaning. In each a long-haired youth reaches toward the sailors for rescue, and they answer by stretching as far as they can. In both there is an imminent threat, be it the sinking Centaur or the ravenous shark. And in both are determined sailors utilizing boat hooks as instruments of rescue. Both Northcote and Copley eschew the gentry, politicians, and officers as central figures in their contemporary historical pieces.

Despite these similarities, with The Sinking of the Centaur, Northcote took a different approach to sailors in high art. They are rescuing themselves, and Baylis only by extension. Where Watson and the Shark is triumphant in overcoming adversity, the sailors of the Centaur are desperate. Copley would not dictate precisely how sailors would be portrayed in the future of high art, nor is there any indication that he wished to.

Copley’s real accomplishment was bringing the common sailor to the forefront. He elevated common sailors from the broadside ballad and cartoon to worthy subjects of refined paintings. Future generations would elaborate on Copley’s innovation, with Northcote being only the first to explore this new subject. The French artist Théodore Géricault painted the famous Raft of the Medusa in 1818, further mingling classical themes with common sailors.[25]

John Singleton Copley’s painting still impresses today. Standing in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, looking up at the six-foot tall, seven-and-a-half-foot wide canvas is daunting. The figures are almost life size. Even though these men occupied a spot near the bottom of the social ladder, they are depicted here as angelic figures descending from on high to save the distressed, naked mortal in the waters below. Copley, in this masterful work, has taken the sort of seaborne rescue that occurred daily in the British Atlantic world and transformed it into an act of metaphysical significance. In the tumult of the American Revolution, the common sailor was no longer a mere participant. Jack Tar is Britain’s savior.

[1] London Evening Post, April 28-30, 1778, 3.

[2] L. F. S. Upton, “Watson, Sir Brook,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5, University of Toronto/Université Laval, accessed March 13, 2017, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/watson_brook_5E.html.

[3] Dr. Bryan Zygmont, “Benjamin West, The Death of General Wolfe,” Khan Academy, accessed March 6, 2017, https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/art-americas/british-colonies/colonial-period/a/benjamin-wests-the-death-of-general-wolfe.

[4] Letters & Papers of John Singleton Copley and Henry Pelham, 1739-1776 (Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society, 1914), 226.

[5] David Cordingly, Ships and Seascapes: an Introduction to Maritime Prints, Drawings and Watercolours (London: Philip Wilson Publishers, 1998), 151.

[6] Edward Ward, The Wooden World Dissected, Seventh Edition (London: Booksellers of London and Westminster, 1760), 2.

[7] Johann Conrad Döhla, A Hessian Diary of the American Revolution, Bruce E. Burgoyne trans. (University of Oklahoma Press, 1990), 15

[8] See also: British Resentment or the French fairly Coopt at Louisbourg, Louis Pierre Boitard, 1755, Colonial Williamsburg; The Times, artist unknown, 1762, Yale University Lewis Walpole Library; The roasted exciseman, or, The Jack Boots exit, E. Sumpter, 1763, Yale University Lewis Walpole Library; Monsieur Sneaking Gallantly into Brest’s Skulking Hole after receiving a preliminary Salutation of British Jack Tar the 27 of July 1778, W. Richardson, 1778, John Carter Brown Library; Don Barcello, Van Trump, & Monsieur de Crickey Combin’d together, Thomas Cowley, 1780, British Museum; The Dutchman in the Dumps, William Humphrey, 1781, John Carter Brown Library; The Dutch in the Dumps, Hannah Humphrey, 1781, British Museum; Jack England Fighting the Four Confederates, John Smith, 1781, Yale University Lewis Walpole Library; Oh! Lord Howe – they Run, or Jack English Clearing the Gangway before Gibraltar, Thomas Colley, 1782, British Museum; The British Tar’s Triumph, Thomas Colley, 1783, British Museum.

[9] “A New Song,” The Royal Magazine, March, 1760, 43.

[10] “Royal Academy Exhibition” Public Ledger, April 28, 1778, 2.

[11] Evan Thomas, John Paul Jones: Sailor, Hero, Father of the American Navy (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2003), 113-128.

[12] Letters & Papers of John Singleton Copley, 98.

[13] Ethan Allen, A Narrative of Col. Ethan Allen’s Captivity (Walpole, New Hampshire: Charter & Hale: 1807), 48-50.

[14] William Dunlap, History of the Rise and Progress of the Arts of Design in the United States, (New York: George P. Scott and Printers, 1834), 1:117.

[15] Thomas Colley, “The English Lion Dismember’d,” 1780, British Museum, accessed March 8, 2017, http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?objectId=1449654&partId=1.

[16] “La Grande Bretagne motile; Das verstunelte Britanien,” The European Political Print Collection, American Antiquarian Society, 1767-1768, Box 1, Folder 2, BM 4183a, accessed March 7, 2017, http://www.americanantiquarian.org/Inventories/Europeanprints/b1f2.htm.

[17] “The Colonies Reduced,” The European Political Print Collection, American Antiquarian Society, 1767, Box 1, Folder 2, BM 4183, Accessed March 7, 2017, http://www.americanantiquarian.org/Inventories/Europeanprints/b1f2.htm.

[18] Donna Mann, “Watson and the Shark by John Singleton Copley,” National Gallery of Art, accessed March 7, 2017, http://www.nga.gov/feature/watson/story1.shtm.

[19] John Singleton Copley, “Rescue Group, 1777/1778,” Detroit Institute of Art, accessed March 8, 2017, http://www.dia.org/object-info/06800f7e-a860-4c9e-b752-4889589d9a8b.aspx?position=6.

[20] Donna Mann, “Watson and the Shark by John Singleton Copley,” National Gallery of Art, accessed March 7, 2017, http://www.nga.gov/feature/watson/history13.shtm.

[21] General Advertiser and Morning Intelligencer, April 27, 1778, 4.

[22] Public Advertiser, April 28, 1778, 2.

[23] Henry Colburn, “Table Talk: On the Old Age of Artists,” Colburn’s New Monthly Magazine, Volume 8, (London: S. and R. Bentley, 1823), 213.

[24] John Nicholson Inglefield, Captain Inglefield’s Narrative, Concerning The Loss His Majesty’s Ship The Centaur, of Seventy-four Guns (London: J. Murray: 1783), 6-28.

[25] Laveissiere S., Michel R., Chenique B., Géricault, exhibit catalog, (Paris: Grand Palais, 1991-1992), accessed March 13, 2017 http://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/raft-medusa.

One thought on “Hearts of Oak on Canvas: Watson and the Shark”

Terrific! Watson and the Shark is an amazing work, and your analysis truly does it justice. I hadn’t consciously noticed the St. Michael reference, but it seems obvious, now. I HAD, however, recognized it’s similarity to depictions of Britain’s Patron, St. George. Incidentally, this painting is the best period illustration I have yet found, depicting the wearing of shoes in “sailor fashion”, as mentioned by Cuthbertson, in 1768.