The lives of the Revolutionary era’s extraordinary women have long been celebrated. At historic sites throughout our country, visitors can learn the stories of Margaret Corbin, Phyllis Wheatley, Abigail Adams, and others. But the experiences of women who did not fight in battle, write poetry, or dabble in politics are not as often interpreted. Nostalgia for battlefield heroics or political dramas has long brought men to center stage, as well as a handful female characters who performed those same gendered roles. All the while, the experiences of ordinary women are frequently left in the wings.[1]

Abigail Hartman Rice was an ordinary woman of the Revolutionary Era. She lived with her family about thirty miles outside of Philadelphia in Chester County, Pennsylvania. She was an immigrant, who crossed the Atlantic a quarter century before the War for Independence began. She had personal encounters and connections with notable individuals: Anthony Wayne, Peter Muhlenberg, and according to family lore, George Washington. She was a Continental Army nurse, who served on the front lines fighting diseases for multiple years. And she delivered twenty-one children in her lifetime, seventeen of which lived to adulthood. And yet, despite all these experiences, there is no evidence to suggest that Abigail Hartman Rice was exceptional in her time. In fact, what makes her extraordinary to Americans today is her very ordinariness.

But beyond these startling facts, her life demonstrates how the support of women was an important factor in determining the outcome of the American Revolution. Despite the limitations placed on them by their eighteenth century society, women found ways in the Revolutionary era to assert themselves. They made certain demands of their superiors. Abigail was not merely an observer of the American Revolution; she was a participant in it. And her life illustrates the complicated ways in which the politics and interests of women could have real, tangible effects on the course Revolutionary War.

Abigail Hartman sailed to Philadelphia with her parents, Johannes and Margaret Hartman, in the summer of 1750. Abigail was one of tens of thousands of German-speaking peoples who came to the thirteen colonies in the eighteenth century. Overpopulation in central Europe, resulting land scarcity, and the active recruitment campaign to coax individuals to immigrate to the New World encouraged families like the Hartmans to make the dangerous voyage across the Atlantic. In the spring of 1750, Abigail boarded a ship named Royal Union in Rotterdam, along with roughly five hundred other passengers. They sailed from the Netherlands, to Portsmouth, Cowes, and then to Philadelphia. One passenger, Gottlieb Mittelberger, described the voyage.

During the journey the ship is full of pitiful signs of distress—smells, fumes, horrors, vomiting, headaches, heat, constipation, boils, scurvy, cancer, and similar afflictions… add to all that shortage of food, hunger, thirst, frost, heat, dampness, fear, misery, vexation, and lamentation as well as other troubles. Thus, for example, there are so many lice, especially on the sick people, that they have to be scraped off the bodies.

Powerful thunderstorms rocked the seas and frightened passengers, who became “convinced that the ship with all aboard is bound to sink. In such misery all the people on board pray and cry pitifully together.”[2]

Royal Union made landfall in Philadelphia on August 15, along with ships from Portugal, Madeira, and the Caribbean. Young Abigail was not quite eight years old when she descended the gangplank alongside her family and set foot in North America. Luckily for Johannes Hartman and his family, they found opportunity in Pikeland, located in the upper part of Chester County, near the Schuylkill River. But not long after arrival, Abigail’s father found himself in the middle of bitter land dispute. The Hartmans and their fellow tenants were involved in pesky land ownership quarrels as the acres changed hands between speculators, including at one point a future Continental Congressman. But despite the contention, Abigail’s father was a diligent farmer of his designated tract.[3]

The Hartmans’ German-speaking neighbors also played significant roles in the American Revolution. The nearby Hench and Rice families would later contribute time, effort, and blood to the Revolutionary cause. Several Hench children fought in the War for Independence and married into the Hartman line. In the two decades prior to the Revolution, these families worshipped at St. Augustine’s Lutheran Church, in Trappe. They attended services regularly, despite a journey of about a dozen miles on bridle paths and across the Schuylkill. Their pastor was Henry Muhlenberg, the father of the North American Lutheran church and future Continental army Brigadier General John Peter Gabriel Muhlenberg. Henry Muhlenberg confirmed Abigail in his parish when she was fifteen years old.[4]

Abigail Hartman most likely met her future husband, Zachariah Rice, before her adolescence. By the time the Seven Years’ War started, Zachariah was a young man in his early twenties. In 1757, when Abigail was sixteen, they married in a ceremony performed by Muhlenberg. Two years later, at age eighteen, Abigail delivered their first child, a son named John. According to the Rice family bible, between 1760 and 1774, she delivered a baby each of those fourteen years except 1766. Her family lived on a farm along the Pickering Creek, where Zachariah built a clover mill in the 1760s. About that time, local Lutherans established a log church named St. Peter’s up the road from their home. There, Abigail, Zachariah, and their children could worship and evade the arduous journey to Trappe.[5]

As their family grew in the 1760s, so too did colonial resentment against the Crown. The German speaking community near Pikeland began to take sides. No doubt that Abigail and her extended family wrestled with these decisions. Her father, Johannes, had been a soldier in the British army during the Seven Years’ War, and fought at Fort Duquesne. Her older brother Peter Hartman accompanied his father west on this expedition as a drummer boy, and officially enlisted the British army in 1758. Abigail had watched her father and brother go off to fight in the Great War for Empire, and had some understanding of the geopolitical stakes of an American Revolution.[6]

Sure enough, when war did come, Abigail’s community looked to her family for political leadership. In 1774, Johannes Hartman, a staunch Whig, joined the local Committee of Safety. A year later Abigail’s brother Peter joined their father on the same committee. The men enforced the acts of the Continental Congress convening downriver in Philadelphia. But the war demanded even greater service. Peter Hartman became a captain in the Chester County Militia in September of 1776. He was later promoted to major, and commanded the 1st, 2nd, and 4th Pennsylvania Battalions at various points between 1777 and 1781. Abigail’s son-in-law, John Hench, served in her brother’s 4th Pennsylvania Battalion in 1777. Her family members were not ragtag farmers who threw down their plows and picked up their muskets in bursts of patriotism. Rather, they were respected and committed public figures, aware of the political and military crisis of the Revolution, and certainly cognizant of the war’s stakes.[7]

At times, the Revolution even called Abigail’s husband Zachariah to the battlefield. His name appears on the list of Chester County militia soldiers in 1777 and 1780. But unlike many of the soldiers in the regular army, Zachariah Rice had property, a living, and fifteen children. Despite his political leanings, he could not leave behind the clover mill and his children for years. The strains placed on him by his family prevented his enlistment in the Continental army. Abigail’s family would have to find other ways to fight for independence, even if her children’s father could not fight against the British.[8]

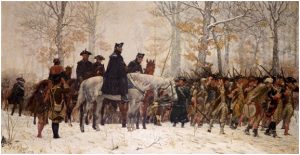

In 1777, the war came to Chester County. The Continental army and the Crown Forces fought the Philadelphia Campaign all over the countryside. They clashed for the first time along the Brandywine Creek on September 11. The defeated Continentals marched into Chester County a few days later. The armies maneuvered into position, but a heavy rain that fell on September 16 prevented any major engagement. Following the near clash known as the battle of the Clouds, General Washington maneuvered his water-logged army through Pikeland towards Yellow Springs. According to the family bible, as the commander-in-chief rode at the head of the column, he stopped at the Rice home. Abigail and her children provided the general and his staff something to drink. That night, Brig. Gen. “Mad” Anthony Wayne’s soldiers encamped on the Rice’s property as the rain continued to fall. Ten days after the battle of the Clouds, Philadelphia fell to the Crown Forces. On October 4, Washington’s attempt to take back the American capital failed at Germantown.[9]

The armies continued to engage with some strength until the winter set in. On December 19, Washington led his roughly 12,000-man army into their third winter encampment at Valley Forge. A host of problems awaited the Continentals in the southeastern Pennsylvania hills. One of the worst supply crises of the war meant soldiers were hungry, and malnourished. After a series of battlefield defeats there was a dire need for more organized training and discipline. But for the time being, the deadliest enemy the army had to contend with was not the British, but disease. Before army marched out of the encampment in June, between 1,800 and 2,000 men would die of illness, more men than were killed at any single battle of the war.[10]

In this struggle to keep the army alive, Abigail and her family played a significant role. On January 3, 1778, with disease rates in his army rising, Washington authorized the construction of a new military hospital at Yellow Springs, about ten miles from Valley Forge. Yellow Springs hospital was the Continental army’s first permanent military medical facility. Zachariah Rice helped construct the building known as Washington Hall. By the time the hospital was completed, the structure measured one hundred and six feet by thirty-six feet. On the first floor, a visitor could meet with doctors and nurses in the kitchen, dining room, or one of the utility rooms. Hospital administrators kept soldiers in one of two wards on the second floor, or in more private rooms on the third floor. And a nine-foot wraparound porch on the first two floors provided some breathing room to the men cramped indoors. 1,300 soldier patients were treated at Yellow Springs throughout the six-month encampment. [11]

The hospital was about a mile from Rice family farm along the Pickering Creek, and it is unclear when Abigail first visited Yellow Springs. Perhaps it was to see her husband as he labored to complete the building. At first, it appears that Abigail came to Yellow Springs not to treat the men, but to support them and possibly buoy their spirits. A descendant of hers wrote that Abigail “came on her errands of mercy, carrying foods and delicacies to the sick and wounded soldiers.” With over a dozen children to provide for, and more on the way, we can imagine that Abigail hoped to remain out of the war’s vortex. But the trips to Yellow Springs became more and more frequent, and soon she was tending to the soldiers.[12]

Conditions in the hospital are hard to imagine today. With relatively primitive knowledge of proper medical procedures, with no conception of germ theory, life inside was probably appalling. The illnesses themselves were unpleasant; typhus, typhoid fever, dysentery, pneumonia were common. Doctors with the help of the nurses frequently performed amputations, especially when frostbite set in during the winter months. Moreover, throughout the war Yellow Springs struggled to obtain necessary medical supplies. Requested items like blankets, clothing, soap, and liquor arrived at sporadic intervals. In May of 1780, Dr. Bodo Otto, the hospital’s director, wrote to the Continental Congress that “necessary stores for the sick are entirely exhausted.” He continued,

There is no money in the hands of the Commissary to purchase fresh provisions, so the sick have been obliged these several past days to eat salt provisions. There is but six days’ supply of bread on hand, and the gentlemen who have furnished us that article as well as meat for the two years past now refuse to supply us any longer. [13]

But for all the discussion of logistics and deplorable conditions, Yellow Springs was not merely a hospital; it was also a site where female nurses developed a modest political voice. In that same letter from May, Bodo Otto described how nurses “refuse serving any longer, as they have received no pay.” The Yellow Springs nurses, typically marginalized by society at large and often considered the physical property of their husbands, raised their voices to demand the money they had been promised. Moreover, Washington and Congress heeded their protests and resolved the issue. By the end of the war, some nurses earned greater pay than enlisted men.[14]

But the nurses’ political clout did not stop there. In January 1781, Bodo Otto sent a letter to the President of the Pennsylvania Assembly, requesting the assembly look into freeing three Chester County soldiers, “young men” who “by their willingness on every occasion, [have] shown their patriotism and fidelity to their country.” The British imprisoned the “boys” in New York City, where possibly some 30,000 Continentals were housed throughout the war. Two of the young men, Henry and John Hench, were the children of Abigail’s neighbors from Pikeland. The captives’ mother, Christina Hench, served as a nurse at the Yellow Springs hospital as well. By 1781, the people living around the hospital were calling on the military facility to assist them in other matters. And because Christina Hench served as a nurse at the hospital like her neighbor Abigail Rice, we can picture a scenario wherein the nurse asked her supervisor, Dr. Otto, to send a letter to the state government begging for their aid. Even if Christina Hench did not request the letter personally, her connections with the hospital certainly made such correspondence possible.[15]

By the early 1780s, the Continental Army and local governments had to reckon with the grievances and tribulations of the Yellow Springs nurses. Thanks to the work they performed and the people they knew, the women of the hospital (Abigail, Christina, and others) advocated for themselves and their family members. While denied many of the rights and protections afforded to their husbands and sons, the Yellow Springs nurses still managed to use their position to make demands of the authorities. They were successful in earning higher pay, but Otto’s letter to the Pennsylvania Assembly could not save lives of Christina Hench’s sons. They died on prison ships, and their remains were later interred in the graveyard at Trinity Church.[16]

Abigail Hartman Rice paid the ultimate price for her service at Yellow Springs. During her time at the hospital, she contracted typhoid fever from one of the soldiers. She had several complications from the illness, and was never able to fully recover. In 1789, she died at home still suffering from the disease she contracted years prior. At the time of her death, there are no records to indicate that anyone celebrated or honored her service at Yellow Springs. Nor for that matter did anyone see fit to remember how she traveled to North America and established a life in a foreign land with no connections. But those in her circle did understand the incredible legacy she left behind. When she was laid to rest in the cemetery near St. Peter’s Church in Pikeland, her first gravestone read, “Some have children, some have none, here lies the mother of twenty-one.”[17]

Two years before he lost his wife, Zachariah Rice was thrown into disputes over his property in Pikeland. Thanks for faulty mortgages and multiple owners, Rice stood to lose his mill and farm. One year after he buried Abigail, Zachariah lost his home and the clover mill farm to foreclosure. He moved most of his family further west, to Juniata County, where he lived until he died 1811. Their seventeen surviving children spread out throughout the growing country. Some settled in Virginia, the Ohio Territory, although many stayed around Juniata and Lancaster counties. Their youngest son Benjamin lived through the outbreak of the American Civil War in the spring of 1861.[18]

Since she died in 1789, the descendants of Abigail Rice have continued to honor her memory. Her own chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution has been established. A new headstone has been laid in St. Peter’s Cemetery in Pikeland, honoring her service as a nurse at Yellow Springs. And there is a memorial plaque dedicated in her memory in the bell tower of the Washington Memorial Chapel, at Valley Forge National Historical Park. And yet, while the memorials are patriotic and evocative, no memorial can or has captured the full experience of her life: her voyage to the New World, her family’s early struggles in Chester County, her role as an eyewitness to the Philadelphia Campaign, and her participation in the revolutionary cause.

Abigail Hartman Rice’s life was extraordinary in its scope. But arguably, what is more fascinating, or impressive, are the ways in which ordinary women made their voices heard in the revolution. Without battlefield heroics, published poems, or connections to politicians, women asserted themselves into the politics of their times. By their presence, and their children’s presence, women helped determine who could and could not enlist the Continental Army. That fundamental decision made by so many families like the Rice’s is often overlooked, but it was a way in which wives could assert themselves into the politics of the Revolution. When organized, women demanded what was rightly owed them, such as the Yellow Springs nurses’ ultimatum for their earned pay. And further still, the opportunities the war created for women in the Continental army provided them an avenue in which they could voice concerns. In this time of tremendous social and political upheaval, women found ways to advocate for their wants and interests.

Our history will continue to celebrate Revolutionary women who performed the roles typically performed by men. Stories of camp followers who seized a moment by stepping into battle tug at heartstrings and demonstrate that women have been successful no matter their circumstances. Often lost in these kinds of stories, however, are the everyday characters who did not receive wounds in battle, like Margaret Corbin did. And not all sacrifices in the American Revolution were on the battlefield. “Ordinary women” helped influence the course the war took in many ways. Abigail Hartman Rice helps us understand how that was possible in the Revolutionary Era.

[1] In a review of Hamilton: An American Musical, R.E. Fulton examined how women’s history is used throughout the musical, and “that even if women do not seem to act in history, they lived the very history they appear absent from.” See R.E. Fulton, “Back in the Narrative: Hamilton as a Model for Women’s History,” Nursing CLIO, May 24, 2016, https://nursingclio.org/2016/05/24/back-in-the-narrative-hamilton-as-a-model-for-womens-history/.

[2] Israel Daniel Rupp, A Collection of Upwards Thirty Thousand Names of German, Dutch, Swiss, French and other Immigrants in Pennsylvania from 1727 to 1776 (Philadelphia: IG. Kohler, 1876; Internet Archive), https://archive.org/details/collectionofupwa00rupp, 228; Aaron Spencer Fogleman, Hopeful Journeys: German Immigration, Settlement, and Political Culture in Colonial America, 1717-1775 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1992), 4-6; Peter Hartman in Pennsylvania Veterans Burial Cards, 1929-1990; Series No. 1, Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission; Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, Ancestry.com; Gottlieb Mittelberger, Journey to Pennsylvania, ed. and trans. Oscar Handlin and John Clive (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1960), 11-13.

[3] Fogleman, 74-77; 80; The Early History of St. Peter’s Pikeland United Church of Christ: Early Historical Background (1700-1812) Prepared in 2011 for our Bicentennial Celebration (Chester Springs, PA; Ebook), 6-7, 34; Rupp, Collection, 228; “Custom House, Philadelphia, Entered Inwards,” The Pennsylvania Gazette, August 23, 1750, The Pennsylvania Gazette Collection, Accessible Archives; Mittelberger, 16-17.

[4] Early History of St. Peter’s Pikeland, 42; James E. Gibson, Dr. Bodo Otto and the Medical Background of the American Revolution (Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas, 1937), 183; Lelia Dromgold Emig, Record of the Annual Hench and Dromgold Reunion Held in Perry County, Pa., from 1897 to 1912 (Harrisburg: United Evangelical Press, 1913; HathiTrust), http://catalog.hathitrust.org/api/volumes/oclc/14048083.html, 78.

[5] Early History of St. Peter’s Pikeland, 42-4; Emig, 78-80; Winthrop Randolph Endicott in U.S., Sons of the American Revolution Membership Applications, 1889-1970, Ancestry.com; Pennsylvania Archives, Series 3, Volume XI, Transcript of the Tenth Eighteenth Pence Rate, Fold3, Vol. XII, 88.

[6] Levi B. Beerbower of Elizabeth NJ, in U.S., Sons of the American Revolution Membership Applications, 1889-1970, Ancestry.com.

[7] “Lineage Book of the Charter Members of the DAR,” vol. 47, North America, Family Histories, 1500-2000 Ancestry.com, 5; Early History of St. Peter’s Pikeland, 44-45.

[8] “Zacaira Rice” in Pennsylvania, Veterans Burial Cards, 1777-2012, Ancestry.com; Early History of St. Peter’s Pikeland, 46.

[9] According to the family bible, Washington stopped at the Rice property after the battle of Brandywine. Which would have been almost impossible, as Washington’s retreat on September 11 was towards Philadelphia, not north to Pikeland. If this meeting with Washington happened at all, it would have happened sometime around the battle of the Clouds. See Emig, Record, 78-84; Early History of St. Peter’s Pikeland, 45.

[10] Abigail’s brother Peter assisted the army that winter by “scouring the country begging for provisions fodder,” which he then personally hauled to the encampment, see SOAR Application of Levi B. Beerbower, Ancestry.com.

[11] Richard L. Blanco, “American Army Hospitals in Pennsylvania during the Revolutionary War” in Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 48, no. 4 (1981): 364-65; Oscar Reiss, M.D., Medicine and the American Revolution: How Diseases and their Treatments Affected the Colonial Army (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 1998),196-97; Gibson, Dr. Bodo Otto, 152.

[12] 1912 Application to the District of Columbia Chapter of the Sons of the American Rev and Winthrop Randolph Endicott in U.S., Sons of the American Revolution Membership Applications, 1889-1970, Ancestry.com.

[13] Gibson, Dr. Bodo Otto, 154, 157, 181-2.

[15] Ibid., 183; Edwin G. Burrows, Forgotten Patriots: The Untold Story of American Prisoners during the Revolutionary War (New York: Basic Books, 2008), 200-01; Early History of St. Peter’s Pikeland, 44-45.

[16] Early History of St. Peter’s Pikeland, 44-45.

[17] Withrop Randolph Endicott SOAR Application, Ancestry.com; Maria Appolonia “Abigail” Hartman Rice, FindAGrave Database, http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=32238493.

[18] Conrad Rice in Kreide Family Tree, Ancestry.com; Emig, 82-84.

4 Comments

Interesting story of some behind the history books facts . The true grit of our Americana displayed by immigrants who formed the great nation in which we live in to this day ,as a free people .

She is my 7th Great Grandmother. Thank you so much for this amazing history of her life.

She is my 6th Great-grandmother. Her legacy of service has carried down through the generations.

A group of descendants have been doing research to reinstate Abigail as a Patriot of the Revolutionary War. There was a Daughters of the American Revolution chapter named for her based on her service, but the National Society of the DAR revoked it in the early 1990s because they said her service could not be proven. My email address is ly************@ya***.com if you would like to be on the distribution list to learn more about what we have discovered.