Gen. George Washington, from the point of view of Americans being trapped at “York,”[1] wrote these prophetic words-

These by being upon a narrow neck of land, would be in danger of being cut off. The enemy might very easily throw up a few ships into York and James’ river, as far as Queens Creek; and land a body of men there, who throwg up a few Redoubts, would intercept their retreat and oblige them to surrender at discretion.[2]

But this wasn’t in connection to the famous Siege of Yorktown that we know. The words were written in 1777, four years before Yorktown. Washington was advising Brig. Gen. Thomas Nelson Jr. that he foresaw a natural trap in the plans Nelson had to base American troops at Yorktown as a way to observe British naval convoys. Washington had foreseen the situation that set itself up on the Yorktown peninsula in the spring of 1781. But in 1781, the British “would be in danger of being cut off” and the Americans could “intercept their retreat and oblige them to surrender.”

Washington, camped at Dobb’s Ferry, New York, east of the Hudson River, had spent the spring and summer of 1781 concentrating on plans to attack Clinton’s fully-entrenched British forces within New York City. Retaking New York had been pretty much an obsession with Washington since he and the Continental Army had been badly defeated and driven out of the city in 1776. By mid-July, 1781 Washington and Maj. Gen. Comte Jean de Rochambeau were sizing up the British defenses “on the North end of York Island”[3] in preparation for the assault.

Washington was also aware that the French fleet of Admiral François de Grasse had set sail northward from Cape Francois bound for the American coast. The exact destination of the fleet, however, was still a mystery. It could be New York Harbor; it could be the Chesapeake Bay. To avoid a misunderstanding, Washington left no doubt in Admiral de Grasse’s mind about a New York destination: “… that City and its dependencies are our primary objects.”[4] In the same letter, Washington mentioned that the “relief of Virginia” could – perhaps – be a “second object” if New York somehow became impossible; but that,

I flatter myself the glory of destroying the British Squadron at New York is reserved for the King’s Fleet under your command, and that of the land Force at the same place for the allied arms.[5]

Now jump ahead to August 14 and everything had changed radically! Washington received word from Newport, Rhode Island that Admiral de Grasse would, indeed, sail into the Chesapeake Bay, Virginia within a few weeks, complete with “between 25 & 29 Sail of the line & 3200 land Troops.”[6] To Washington’s credit, he wrote in his personal journal, “Matters having now come to a crisis and a decisive plan to be determined on – I was obliged … to give up all idea of attacking New York.”[7] But things would have to happen fast. De Grasse said his fleet could only stay for two months, and then they would have to head back south to avoid hurricane season on the American east coast.

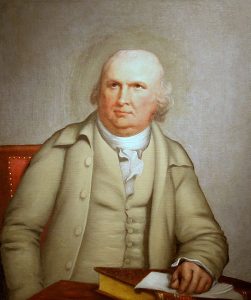

For Robert Morris, a monumental sense of panic replaced any good feelings others had of successful Yorktown plans falling into place. Just three days before, on August 11, Washington had met with “Robt. Morris Esqr. Superintendent of Finance … to make the consequent arrangements for [the Continental Army’s] establishment and support”[8] of the New York campaign. Even with those plans, Morris had been scrambling to find the funds, materials and supplies to finance the joint American-French assault upon New York.

New York’s Out, Yorktown’s In

News of the radical (and expensive) change of strategies left Morris completely rattled as to how to pay for the very long march of the armies southward to Virginia, let alone pay for any action happening once they arrived. Washington asked Morris for an estimate of the new plan’s expenses. On August 21, Morris stalled on the request, saying that he needed time “to consider, to calculate.”[9] At least one good thing came out of the change of objectives: the British were now so sure that New York was the object of the Franco-American attack that Cornwallis had been ordered to entrench in a Virginian seacoast port (Yorktown) and to ready half of his army to ship to New York for needed reinforcements. Cornwallis had inserted himself directly into the Patriot trap.

On August 22, Robert Morris replied to General Washington, telling him the truth. “I am sorry to inform you that I find Money Matters in as bad a Situation as possible.”[10] He added that the states, which had promised to pay their fair share of expenses, had very rarely come through with those payments. All Morris could offer in this next crisis was the value of his personal credit, which even Morris himself was secretly beginning to doubt. Washington told Morris to do what he could since the American and French forces were already secretly moving down from New York to Philadelphia. A small diversionary force was left in New York so as not to tip off the British of their movements.

From Philadelphia, the initial plan was to transport the troops from Chester, Pennsylvania (ten miles to the southwest of Philadelphia) down to Virginia. Washington strongly reiterated that this movement of combined forces to Yorktown was so important, it had to happen. Morris assured Washington that he’d find a way to pay for it. But privately he didn’t know how. The country was absolutely, completely broke.

The same day, August 22, 1781, Morris sent letters to the thirteen states – both trying to shame them and warn them:

We are on the Eve of the most Active Operations, and should they be in anywise retarded by the want of necessary Supplies, the most unhappy Consequences may follow. Those who may be justly chargeable with Neglect, will have to Answer for it to their Country, to their Allies, to the present generation, and to all Posterity.[11]

The Army’s Near Strike for Pay

Now back in Philadelphia, Morris personally followed up his threat-letters to the states with Thomas McKeon, the president of Congress. Morris wanted to put the pressure on McKeon for the funds spelled out by The Articles of Confederation, Article VIII: “All charges of war, and all other expenses that shall be incurred for the common defense … shall be defrayed out of a common treasury, which shall be supplied by the several States …”[12] But because there was no Articles of Confederation enforcement clause, the states gave a pittance to the national treasury, sometimes, whenever they felt like it, and only once their own state needs were taken care of. So essentially McKeon told Morris that the treasury was empty and with state debt and inflation running wild, not to expect any money in the near future … if ever. The proposed Bank of North America, a potential new source of credit and funds, existed only on paper.

Morris had no time and had to act. To fund the Yorktown campaign, Morris was now clutching at desperate financial straws. Based upon his good word and credit alone, Morris printed and issued Office of Finance currency backed only by Robert Morris’s promise to pay. These bills, used as cash, became known as “Morris Notes” around Philadelphia. They paid a few very large and overdue Continental Army bills and kept some small immediate supplies flowing to the American and French armies on the road. (The Morris Notes that could be redeemed immediately were nicknamed “short Bobs,” and the ones with a longer length of time specified were called “long Bobs” – both referring to Morris’ first name of Robert).

But “Morris Notes” weren’t enough, by far, to pay for the Yorktown expedition, and were only stalling tactics by Morris to buy small amounts of time. The next crisis happened when the Yorktown-bound American soldiers arrived in Philadelphia on their way to Chester, the next staging area. The revised plan was that from Chester, the combined French and American forces would march to the Head of Elk, Maryland. At that point, some would sail down the Chesapeake, some would march to Virginia. It was a hot southern summer and the heat and humidity made the soldiers tired, cranky and edgy.

To help with morale, Washington arranged for a festive fife and drum parade through the Philadelphia streets. Although cheered on by residents, the tired, hot, hungry and dirty campaigners almost choked on the dust cloud that their marching feet stirred up. And that wasn’t all. The New England soldiers in particular decided they weren’t budging without getting some pay. They hadn’t been paid in a year and refusing to move from the capital city until they got paid seemed to make perfect sense.

George Washington – again – turned to Robert Morris for help. On August 27, Washington pleaded,

I must entreat you if possible to procure one months pay in specie for the detachment which I have under my command part of those troops have not been paid any thing for a very long time past, and have upon several occasions shewn marks of great discontent… If the whole sum cannot be obtained, a part of it will be better than none.[13]

Morris knew his own Morris Notes wouldn’t appease the belligerent troops. Only “specie” (hard coins) would do, as Washington had said in his letter. Morris was down to his last angle to get some cash – he went across town to have a heart-to-heart meeting with Rochambeau at the house of the Chevalier La Luzerne (Anne-César de La Luzerne), the French Minister to the United States. After listening, Rochambeau said he was hard up for cash, too. But he passed along the rumor that supposedly Admiral de Grasse was bringing with him on his flagship lots of Spanish silver! The bad news was that as far as Rochambeau knew, the coins were just for French use. However he added that the guy who would know more details was the treasurer of the French Special Expedition forces … and uh, unfortunately,- he was on the road to Chester. The whole military plan was in motion, money or not, and Rochambeau himself said he’d be leaving for Chester within hours.

The Two Morris’s Desperate Silver Hunt

Robert Morris rushed back and found one of his best friends (but no relation), Gouverneur Morris, and together the two Morris’s set out on horses to hunt down the French treasurer. They weren’t on the road long when they spotted another rider hurriedly riding toward them. By a fortunate twist of fate, it was a courier who’d been sent by General George Washington with an important packet of letters for “Superintendent of Finance – Robert Morris.” Morris quickly opened the correspondence and sure enough, one letter in particular gave incredible, almost miraculous news! Admiral de Grasse had indeed arrived at Chesapeake Bay and with him – confirmed – were the barrels of Spanish silver!

The Morris’s arrived in Chester and instead of locating the French treasurer, found Rochambeau already there. He had sailed down the Delaware River to save time and was as excited as Robert Morris was with the news of the hard coins having arrived. Morris thought a financial loan might now be authorized on the spot because of Rochambeau’s presence rather than Morris having to find him. The agreement was made. Morris staved off a soldier rebellion of sorts and bought more time for Washington at Yorktown. The deal was that the French would loan Morris twenty thousand dollars in specie coin on the terms that it be repaid by October 1. The next day back in Philadelphia, Morris sent Washington an update along with copies of letters sent to Rochambeau confirming the terms of the loan,

In Consequence of the Conversation I had the Honor to hold with your Excellency yesterday and of your Promise to supply to the United States the sum of twenty thousand Dollars for an immediate Purpose, to be replaced on the first day of October next, I have directed Mr Philip Audibert the bearer of this Letter to wait upon you. I shall be much obliged to your Excellency if you will be pleased to direct that the above Sum be paid to Mr Audibert … I will take Care that the money be replaced at the time agreed upon.[14]

Morris arrived back at the office only to find many other urgent requests for money. The governors of New Jersey and New York lacked the funds to get critically-needed herds of cattle down to the Continental Army. The garrison at West Point needed flour desperately and the state government said it could not help. The field army of Nathanael Greene was close to running out of food. The Virginia troops under the Marquis de Lafayette had chased Cornwallis into Yorktown and were holding them there. But Lafayette said he expected to run out of provisions very soon unless reinforcements and food made it there in time. Robert Morris privately complained within the pages of his diary, “It seems as if every person connected in Public Service entertain an opinion that I am full of money.”[15]

General Washington had departed already in advance of his army marching down to Yorktown leaving the disgruntled troops still sitting in Philadelphia insisting on being paid. Once again, luck smiled upon Morris and the French barrels of silver arrived at the Office of Finance just in time. Robert Morris instructed that John Pierce, Paymaster-General of the Continental Army, should make a spectacle showing of the specie coin when paying the sullen soldiers. So Pierce cracked open the top of one of the barrels and for grand effect, dumped the barrel on its side, letting the silver coins spill out. Crisis averted, and Morris knew word would travel quickly that soldiers were being paid in coins, not Continental dollars, certificates or vouchers.

But the crisis wasn’t averted and Morris would get no letup.

Soon afterwards Gen. Benjamin Lincoln reported to Morris that the coins had run out prematurely and that everyone hadn’t gotten paid!

The total was a little over six thousand dollars short. Lincoln warned Morris, “It will be difficult if not impossible to keep the men quiet who did not receive their pay.”[16] Once again, Morris begged, borrowed and promised, based on no collateral but his good name and credit, and somehow got the money needed. He wrote to Lincoln, “I supplied the Pay Master General with Six thousand two hundred Dollars in preference of the many other demands that came on me.”[17]

Although Yorktown was now financed to happen, fate told Morris the outcome of Yorktown just had to be an allied victory. Money was gone, inflation fears made dollars near useless, and Robert Morris was at the end of his financial ropes. A Yorktown victory would mean new excitement in the international monetary arena and new offers of loans and lines of credit would likely come pouring in from foreign governments. But without a victory, well, Morris told the unvarnished truth to Joseph Reed on September 20, 1781: “The late Movements of the Army have so entirely drained me of Money, that I have been Obliged to pledge my personal Credit very deeply, in a variety of instances, besides borrowing Money from my Friends; and … every Shilling of my own.”[18]

Yorktown had to be a victory. It was “game over” otherwise.

[1] Meaning York-Town, Virginia.

[2] From George Washington to Brigadier General Thomas Nelson, Jr., 2 September 1777, The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 11, 19 August 1777 – 25 October 1777, ed. Philander D. Chase and Edward G. Lengel. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2001, pp. 128–130.

[3] John Rhodehamel, ed., George Washington – Writings, “Journal of the Yorktown Campaign”, (New York, The Library of America, 1997), 440.

[4] From George Washington to François-Joseph-Paul, comte de Grasse-Tilly, 21 July 1781, Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016, (accessed July 27, 2016); http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-06471.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Rhodehamel, George Washington – Writings, “Journal of the Yorktown Campaign”, 451.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid, 450.

[9] Charles Rappleye, Robert Morris, Financier of the American Revolution (New York, Simon & Shuster, 2010), 256.

[10] To George Washington from Robert Morris, 22 August 1781, Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016,(accessed July 28, 2016); http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-06758.

[11] From Robert Morris to The States, 22 August 1781, Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016, (accessed July 28, 2016); http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-06759.

[12] Barbara Silberdick Feinberg, The Articles of Confederation, the First Constitution of the United States (Brookfield, CT., Twenty-First Century Books, 2002), 80.

[13] From George Washington to Robert Morris, 27 August 1781, Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016,(accessed August 1, 2016); http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-06802.

[14] To George Washington from Robert Morris, 6 September 1781, Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016, (accessed August 7, 2016); http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-06904. Philip Audibert, Esq. at this time was assistant paymaster general of the Continental Army.

[15] Robert Morris diary entry, 11 September 1781, The Papers of Robert Morris II, 1781-1784: August-September 1781 (Pittsburgh, PA., University of Pittsburg Press, 1975), 244.

[16] Benjamin Lincoln to Robert Morris, 8 September 1781, The Papers of Robert Morris II, 1781-1784: August-September 1781 (Pittsburgh, PA., University of Pittsburg Press, 1975), 220.

[17] Robert Morris to Benjamin Lincoln, 11 September 1781, ibid, 252.

[18] Robert Morris to Joseph Reed, 20 September 1781, ibid, 309. Joseph Reed at the time of Yorktown was president of the Pennsylvania Supreme Executive Council. Pennsylvania had gone bankrupt the year before and it was Robert Morris who also brought it back into solvency.

12 Comments

Fantastic read! Thank you very much for this wonderfully in depth look at the finances behind what I personally consider to be the make or break moment of the entire War.

Thank you, Kyle. I agree that the siege of Yorktown was crucial and until I looked into this story, I had no idea how very close the whole thing came to never happening because the country was flat broke. (That was a close one!)

It was also flat broke when it again declared war on Britain in 1812. Some things never change….

Gary, a great rule of thumb would be that a country can’t declare war until it can afford it.

John, an excellent, captivating read in which the readers feel the Continental Army’s desperation! Also of note, Rochambeau was also out of funds and needed de Grasse’s silver.

The citizens of Havana provided the funds to de Grasse as part of the Franco-Spanish Caribbean strategy. I wonder if they and the French were repaid?

Thank you, Gene. Yes, even the French were waiting for the French to deliver some hard currency!

Good question about Havana ever being repaid. Maybe it was like some French funds which were considered “gifts” by Americans. Some of that monetary labeling was disputed after the war… for obvious reasons!

Actually, a good portion of the monies collected in Havana to aid in DeGrasse’s northern expedition were ultimately deemed a ‘donation’ made by the city’s population.

There enters that legend of the ‘damas de La Habana’- whom gifted their jewels and wares to aid the patriotic cause of the colonies. But even though Francisco de Saavedra -the regent commissary and coordinator for the Spanish effort at that time- referred to this episode lightly in his journals, the likelihood is that the majority of the monies were raised by Saavedra’s authorization to repay the donors quickly and in specie (and at a premium, kind of like war bonds). Some citizens took advantage of this offer but a great majority wound up looking at the contribution through philosophical eyes.

Thank you for your comments and you raise very good points and a question about any aid (be they “gifts”, “donations”, or “loans”) this young country received from Cuba and its people as well.

This is great it shows how close we were to victory while being at that same distance to defeat it’s something that is almost never taught and I feel like Robert Morris should be considered a hero for it.

Brendan – I completely agree with your feelings about Robert Morris. Always behind the scenes it seems, he made all the difference between success and failure of the Revolution. I’m glad you enjoyed this particular story!

John,

Great read.

There is more to the Yorktown Campaign finance story as outlined by French Commissary Officer Claude Blanchard. The French received two different shipments of hard currency just as the troops began the move south in August of 1781, delivered from France to Boston via French frigates. One of these ships was La Resolute that also carried John Laurens on his return from France. These two shipments were in addition to the hard currency brought north by de Grasse, 800,000 livers in Spanish piastres (silver pieces of eight). Without this influx of hard currency the French Army was also broke (Blanchard, 1876, pp. 128, 133, 140, 143 & 145). This influx of cash likely exceeded 3 million livres. The exchange rate in 1726 was fixed at 8 ounces of gold equal to 740 livres, 9 soles. One livre equaled 18 sols. The livre was discontinued with the introduction of the franc in 1795. If my math is correct and based on the current value of gold, 3 million livres in 1781 would equal $410 million today. On 7 February 1782 the French frigate Sibille delivered another 2 million livres to the French forces in Virginia (Blanchard, 1876, p. 156). Sustaining the French Army in North America was expensive. The French Army officers complained that all prices in war-torn America were highly inflated.

Thank you, Patrick. Some very good additional facts regarding the multiple French hard currency shipments and exchange rates. It’s no doubt that French officers quickly realized that the livres they were receiving just didn’t go that far in America, especially around the inflationary time of the Yorktown siege.