John Fisher hung from a tree. “Near the high road” from Fostertown to Mount Holly, New Jersey, he was in plain sight to the soldiers who marched past.[1] He hung there as an example of what deserters could expect, especially if they were caught bearing arms for the enemy. The impact Fisher’s dangling corpse had on the rank and file soldiers cannot be measured, but it made a strong enough impression on officers that several recorded the grizzly sight in their writings. Today the tree is gone, but a roadside marker commemorates the event that occurred on June 22, 1778, albeit with an error. Fisher’s story, however, has been overlooked.

When war broke out in America in 1775, Englishman John Fisher was a private soldier in the 36th Regiment of Foot serving in Cork, Ireland.[2] The 36th Regiment spent the entire war in Ireland, but not all of the regiment’s soldiers did. When the British army deployed regiments on overseas service, those regiments were brought up to strength using two methods: recruiting, of course, but also by drafting, or transferring, experienced men from other regiments into the deploying regiment. (The term draft, in this context, denoted pulling, as in draft horse or draft beer; the men were pulled from one regiment to another. The word did not refer to civilians pulled into military service, the way it is used today.) Drafting insured that the operational readiness of the deploying regiment was not compromised by having too many new recruits. The 36th Regiment provided over 225 drafts to other regiments in 1775 and 1776, and spent the next few years recruiting and training new men in Ireland. This method of training and deployment worked well for the British army throughout the era. Drafting orders usually directed officers to seek volunteers first, then select men to be transferred if there were not enough volunteers. The regiment receiving the drafts had the right to refuse men deemed unfit, which prevented the giving regiment from dumping unsuitable men.[3]

In early 1776, John Fisher and twenty-eight of his fellow soldiers were drafted from the 36th Regiment into the 28th Regiment of Foot. There, he met up with Irishman John Fisher, a soldier who had joined the 28th Regiment about three years before. One regiment, two John Fishers. This sort of thing wasn’t unusual.[4]

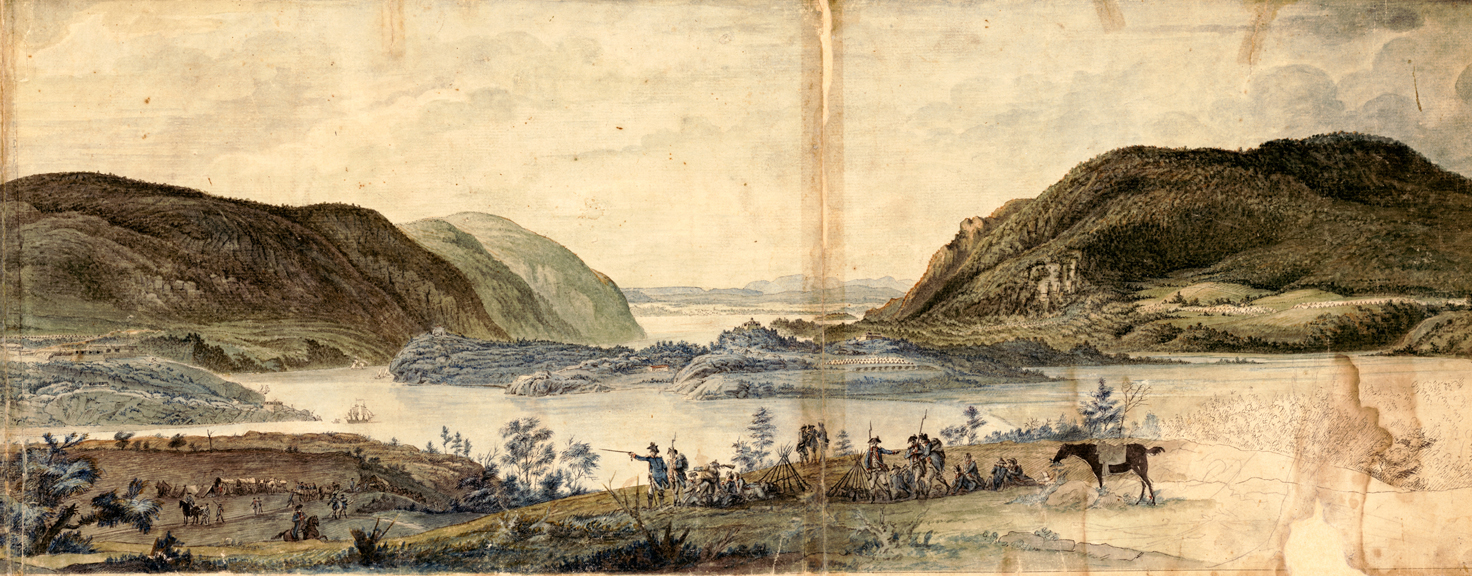

The 28th was one of six regiments on the abortive British expedition to the southern colonies in 1776. When the attempt to take Charleston, South Carolina failed, the troops sailed to New York where they joined General Howe’s army in the campaign that took New York City. Fisher was put into the regiment’s light infantry company and appointed drummer. This was an important assignment, particularly in the light infantry where drummers did not actually play drums, at least not on campaign. For the fast and fluid field maneuvers used by the British light infantry, the hunting horn was the signaling instrument of choice. Besides being easy to carry and having a sound that carried well, using the horn to sound the advance, retreat, and other commands stirred the spirits of British soldiers while humiliating their opponents. Through Manhattan, Westchester county, and into New Jersey, the hunting horn sounded the rout of American troops in the face of a British onslaught throughout the autumn of 1776.

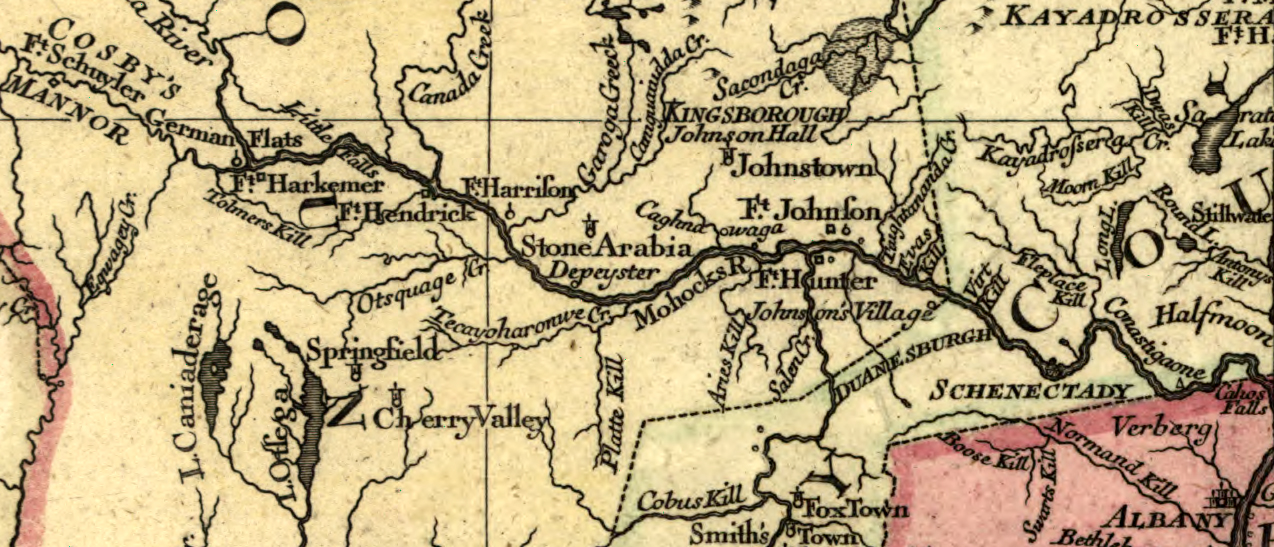

Winter was different. Having established a string of posts stretching from Staten Island to Trenton, New Jersey, the British army stopped campaigning for the months when roads became impassible because of snow and mud.[5] The light infantry battalion that John Fisher served in was quartered in Piscataway. They had crude accommodations in whatever buildings were available, scarcely enough clothing because most of their belongings remained in storage in New York City, and relied heavily on foraging to procure food and firewood. Fortunately, New Jersey was a bountiful place, so food and fuel could be found reasonably easily. It was, nonetheless, dangerous. American soldiers were quartered nearby, just over the Short Hills range to the west of the British posts. Patrols and parties from both sides frequently clashed, and straying far from quarters could be quite hazardous. On April 11, 1777, John Fisher disappeared.

Some months later the British withdrew from the interior of New Jersey, and instead went by sea to Head of Elk, Maryland and then by land to Philadelphia. The light infantry battalion containing the 28th’s company went on this campaign, as did the 28th Regiment itself. After a rigorous campaign that left Philadelphia in British hands but the surrounding countryside firmly in American control, another winter halted campaigning once more.

It was during this winter that an incident occurred which has confused John Fisher’s story. The other John Fisher, who served in a different company, had been appointed corporal. On February 25, 1778, he was tried by a general court martial for raping a nine-year-old girl. She was the daughter of a sergeant and his wife in the 28th Regiment; they’d asked another soldier to take care of her while they went out for the evening, and that soldier, wishing to sleep instead, asked Corporal Fisher to look after the girl. He took very inappropriate advantage of the situation, and in spite of offering an eloquent defense was found guilty by the court.[6]

Cpl. John Fisher, the Irishman who had enlisted in the 28th Regiment in 1772 or 1773, was sentenced to be “hanged by the neck until he is dead.” The execution was to take place on Monday, March 23, on the common in Philadelphia, “between the hours of ten and twelve in the forenoon.”[7] But when the fatal time came, a pardon was granted “in consideration of his youth, and the very good character given of him by the field officers of his regiment.”[8] Corporal Fisher was a free man, and by 1781 had advanced to sergeant in his regiment.

But this story is not about Cpl. John Fisher, it’s about Drummer John Fisher. Because the general orders concerning Corporal Fisher’s conviction and pardon have been published, many have assumed him to be the same man as Drummer Fisher even though the rank is clearly stated in the orders. They were two different men. While Cpl. John Fisher was on trial in Philadelphia in March of 1778, Drummer John Fisher, who had disappeared from the 28th Regiment’s light infantry company in April of 1777, was still nowhere to be found. Three months later, that changed.

The decision by France to join the American Revolution caused a dramatic change in British strategy. Instead of a war on the other side of an ocean, Great Britain was now faced with an age-old enemy just across the English Channel, an enemy with global interests similar to Britain’s. In addition to defending the shores of England and Ireland, the British navy and army had to protect key interests in the West Indies from French invasion. The closest troops were in America, and expanding their responsibilities to include the West Indies meant redistributing those forces. The decision was made to evacuate Philadelphia, a move that was accomplished in June 1778. Lacking sufficient shipping to move everything by sea, the British army set out over land. The bulk of the American army was in Pennsylvania, behind the British route of march, but New Jersey teemed with small bodies of soldiers poised to harass the huge British force that filled dusty roads in the early summer heat.

On June 19, a party of Hessian Jägers, expert riflemen who probed the front and flanks of the British line of march, were fired upon from a clump of woods. The Jägers lost a man, but rushed into the woods and scattered some skulking militia men, most of whom fled. They found one man lying on the ground wounded, wearing a bayonet and cartridge box but with no musket. They took him up and brought him to the British column.

The man they’d captured was John Fisher. He was quickly recognized as a deserter; his own regiment was, after all, part of the army moving across New Jersey. Less than forty-eight hours after his capture, when the army stopped in Mount Holly, Fisher sat before a hastily arranged general court martial, charged with the crime of “having deserted from the said Regiment and born Arms in the Rebel Service.”[9] As the court of thirteen officers (none from the 28th Regiment, to insure impartiality) listened, an officer and a sergeant of the 28th testified to Fisher’s service in the regiment, mentioning that he was a draft from the 36th Regiment and the date he went missing. They affirmed that he had “received Pay and Cloathing,” a critical point because it affirmed that the army had upheld its obligations of the enlistment contract. The sergeant testified that Fisher had taken away only the clothing he wore when he disappeared, differentiating him from men who carefully planned to desert and absconded with extra clothing and other possessions.

Three of the Jägers who captured Fisher were called before the court. These men needed a translator, so a bilingual German serving in the 10th Regiment of Foot was sworn in for that purpose. Through the interpreter, the Jägers related that Fisher was among the five or six rebels who fired on them, after which “the prisoner then threw himself upon the Ground and was wounded and taken.” All concurred that, although he had no musket, he wore the accoutrements of a soldier, a bayonet and a cartridge box.

British military justice was rigidly governed by law; discipline was harsh but not arbitrary. One of the privileges to which John Fisher was entitled was legal counsel from a deputy judge advocate, an officer well-versed in martial law who oversaw the court martial proceedings. By June 1778, many British prisoners of war had made their escape and returned to British service. Some even came in wearing American uniforms, claiming to have enlisted with the enemy in order get close to the front lines so that they could escape. Even if Fisher had not known about this, the judge advocate certainly did, and may have advised Fisher to use this defense.

Fisher claimed that he had not deserted, “but was cut off from his Quarters by a party which came between him and them” when he went to procure some spruce beer for a sick comrade. Unable to return to his quarters in Piscataway, he was “obliged to make his escape to Morris Town,” over fifteen miles to the north and well inside American territory. There, he claimed, he found work as a laborer and also found a woman to marry, in what must have been a quick courtship given that he was gone for a total of only fourteen months. In spite of this secure-sounding situation, he professed “always a desire of returning to the British Army.” He was unable to do so, however, because only soldiers were allowed to go more than a mile into the countryside without a pass. “He enlisted in order to get an opportunity of returning to his regiment,” he said, but refused to go with the party that fired on the Jägers until his captain threatened his life. He asserted that he had not fired on the Jägers, but instead threw down his gun and tried to surrender to them.

Other soldiers had told similar stories in the past, but usually they were men who had come in voluntarily; that is, they had clearly deserted from American service to rejoin the British. Fisher needed a stronger case, because he was with the party that fired on the Jägers. He had something that few others before him had had, though: a witness. While he was in Morristown, he’d come to know another British soldier, a man of the 17th Regiment of Foot named John Hatter who had deserted in New Jersey exactly two weeks after Fisher had disappeared.[10] Hatter rejoined the British army in Philadelphia on February 1, 1778, and was on the march across New Jersey and available to testify on Fisher’s behalf. Fisher told the court that, while in Morristown, he’d told Hatter of his desire to return to British service, and called Hatter before the court for questioning.

Fisher asked one question, hopeful of being exonerated by his old comrade: “Did he ever know the Prisoner to serve or do any thing against his Country?” Hatter, however, did not give the response that Fisher was hoping for; he said that Fisher had indeed served for a month in the militia, “as a Substitute for another Man.” The court then took over the questioning, and asked Hatter if he’d ever heard Fisher “say that he wished to get back to the British Army?” Hatter’s response: “He does not remember that he ever did.” We can only wonder how Fisher reacted to this.

The court, still giving Fisher the benefit of the doubt, pursued another angle: given that Fisher had served as a substitute (that is, he took the place of someone else who was required to serve in the militia), the court asked Hatter if Fisher was “forced into the Army, or put into Goal because he would not serve?” Again, Hatter’s response was incriminating: “No, they never force Deserters to enlist.”

This left one more avenue for the court to probe. Fisher had said that he didn’t desert, but fled to evade capture. What did Hatter know about this? The court asked him, “Did he ever hear him say how he had got away from his Regiment?” For the fourth time, Hatter gave a response that contradicted Fisher’s account: “He heard him acknowledge that he had Deserted.”

The court had heard enough. They found John Fisher guilty and sentenced him to death on June 21, 1778. The sentence was carried out the following morning, using a tree by the road on the army’s route of march, where any soldiers contemplating desertion could ponder his fate. Today a sign marking the spot gives his name as “Corporal John Fisher,” confusing the English drummer with the Irishman who was tried and pardoned four months earlier.[11]

[1] F. A. Whinyates, ed., The Services of Lieut.-Colonel Francis Downman (Woolwich, England: The Royal Artillery Institution, 1898), 66.

[2] Muster rolls, 36th Regiment of Foot, WO 12/5025/2, The National Archives of Great Britain (hereinafter cited as TNA).

[3] For more on drafting, see Don N. Hagist, British Soldiers, American War (Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, 2012), 51-59.

[4] Muster rolls, 28th Regiment of Foot, WO 12/4416 and /4417, TNA. All subsequent information about the service records of these two men are from this source.

[5] “Bloody Footprints in the Snow? January 1777 at Brunswick, New Jersey” by Linnea M. Bass, Military Collector & Historian number 45 (Spring 1993), 9-10.

[6] Trial of Cpl. John Fisher, WO 71/85, 290-307, TNA.

[7] General Orders, March 16, 1778, in “The Kemble Papers,” Collections of the New York Historical Society for the Year 1883 (New York: New York Historical Society, 1884), 1:556.

[8] Ibid., 1:560.

[9] Trial of Drummer John Fisher, WO 71/87, 202-208, TNA. Subsequent information about Fisher’s trial is from this source unless otherwise cited.

[10] Muster rolls, 17th Regiment of Foot, WO 12/3406/2, TNA.

[11] The marker is on Burlington County Route 543, three-tenths of a mile east of the intersection with Petticoat Bridge Road, near Columbus, New Jersey (40° 4.33′ N, 74° 43.854′ W).

2 Comments

I am reading this story in Mount Holly itself, so I’ll add a few additions: In 1775 the Quakers built a meeting house which is still smack in the middle of town, and there is a bench inside with cleaver marks where the British or Hessians (allegedly) chopped meat. The meeting house is on a road that goes forty miles straight to Monmouth – site of the battle six days after the hanging – but that road did not exist in 1778, so the British took a roundabout route through farm country past once important towns which are now just overlooked villages. On the route is another Quaker Meeting House that is now a private home which (allegedly!!) has bloody hand prints from a skirmish a few days before Washington’s Crossing. And Petticoat Bridge Road is still there and goes through farmland, so it looks very much like it must have in 1778.

Shouldn’t the sign read “hanged’ and not “hung”? I believe this would be correct grammar…pictures are hung; people are hanged.