Arlington National Cemetery’s founding story is well known. During the American Civil War, Union forces occupied Robert E. Lee’s 1000-acre estate on the Potomac River directly across from Washington, DC and, as a form of retribution for Lee joining the Rebel cause, turned it into a cemetery. What is lesser known is the link between the resulting modern day national shrine and the American Revolution.

In 1778, John Park Custis, son of Martha Washington and stepson of George Washington purchased land on the Virginia side of the Potomac. Custis passed the land to his son George Washington Parke Custis who built a mansion on the property and named it Arlington after the Earl of Arlington, the source of the family’s original land grant. Custis had only one child, Mary, who brought the estate to her marriage with Robert E. Lee in 1831. The Civil War ended the Custis-Lee family ownership and Arlington Cemetery has become America’s most venerated national memorial honoring its valiant military heroes.

The 640-acre Arlington Cemetery is a sea of grave markers and memorials with only eleven out of the over 400,000 graves containing the remains of Revolutionary War veterans. While these eleven veterans are not household names today, they made significant contributions and sacrifices for independence. Over half served more than five years, which is a combat duration only exceeded by today’s veterans of the twenty-first century wars in the Middle East and Afghanistan. Five of the eleven were taken prisoner and three were wounded. None of them died in battle and after the war, all created enough social standing to be to be remembered with marked gravesites. The following step-by-step guide will aid visitors in finding these grave locations and learning more about the Revolutionary War veterans interred within the cemetery.

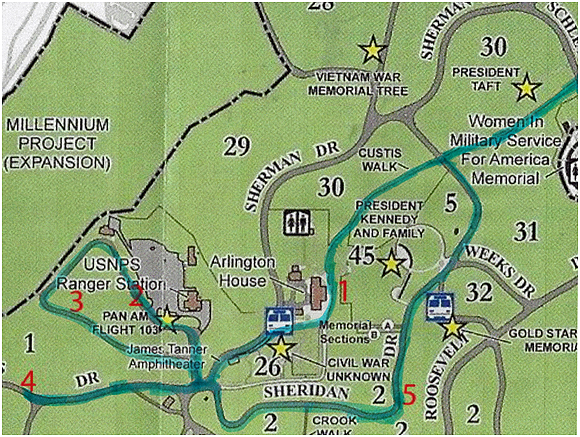

All of Revolutionary War veterans are buried in two of the seventy burial sections within the gently rolling hillocks of Arlington Cemetery. Making for easy access, all of the eleven graves are located within four rows of a street or path. The tour is divided into five stops, each of which is described below along with information to aid in locating the Revolutionary War sites. Start from the Visitors’ Center and walk to Arlington House (the Custis-Lee Mansion). My favorite route to the mansion is the scenic and more secluded Custis Walk, which is accessed out of the north end of the Women in Military Service Memorial.

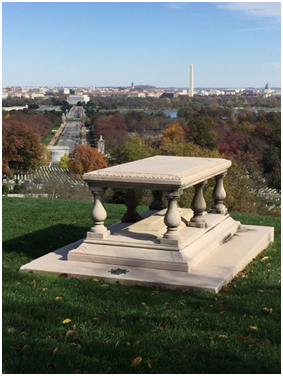

Stop 1 – In front of Arlington House overlooking Washington, DC

Pierre Charles L’Enfant, the initial Washington, DC city planner, is buried in a prominent place outside the front door of Arlington House overlooking the city he helped to develop. What is lesser known about L’Enfant is that during the Revolution, he came to the United States from France and had a notable military record. In 1777, the Continental Congress commissioned L’Enfant a lieutenant in the Corps of Engineers. While at Valley Forge, L’Enfant illustrated Baron von Steuben’s famous drill manual. In April 1779, L’Enfant received a promotion to Captain of Engineers and served on Steuben’s staff including a stint at West Point.[1]

To support an emerging need for engineering expertise, L’Enfant transferred to the Southern Department. On October 9, 1779, while operating as an infantry officer under the command of John Laurens, L’Enfant led a daring attempt to ignite the abatis in front of British defenses at Savannah, Georgia. Severely wounded and presumed dead, he lay at the site of the failed assault. In the battle‘s aftermath, Patriot forces discovered that he was alive and transported him to Charleston to recover. While convalescing, he became a British prisoner when Gen. Benjamin Lincoln surrendered the city. Later exchanged, he served in Philadelphia and received a brevet promotion to major near the end of the war. As a reward for his military service in the Revolution, L’Enfant was granted 300 bounty acres.

L’Enfant gained the confidence of Washington as a competent artist and designer. In 1778, L’Enfant drew a likeness of Washington, which unfortunately does not survive today. As the Revolution ended, L’Enfant designed the insignia for the Society of the Cincinnati and traveled to France in late 1783 to enroll French officers in the Society.[2] When Washington sought an architect to design the new capital city, he turned to L’Enfant for the job. However, L’Enfant created controversy and the commission was not completed. He stayed on in America, but was unsuccessful as a commercial architect. He died in poverty and was buried in a non-descript grave on a Maryland farm.

In the early twentieth century, L’Enfant’s reputation as the innovative city planner of Washington, DC was rehabilitated. As a result, by order of Congress in 1909, his remains were disinterred and brought to the United States capitol where they lay in state before reburial at Arlington.[3] During the interment ceremony, Senator Augustus Octavius Bacon placed his own Society of the Cincinnati gold medal in the grave, recognizing L’Enfant’s membership in the Society and his design of its medal.[4]

Stop 2 – Lexington Minuteman Memorial and Seven Revolutionary War burial sites in the Officers Section (Section 1-297 to 314)

A ten-minute walk westerly from the mansion leads visitors to Officers Section, the site of the Lexington Minuteman Memorial and the burial plots of seven of the eleven Revolutionary War veterans. On the left side of Humphrey’s Drive, John Follin’s large gravestone is a prominent marker to guide you to this stop. The other six graves are a few paces from Follin’s grave marker and the Lexington Minuteman Memorial is directly across Humphrey’s drive in front of an eastern hemlock memorial tree.

In 1911, the remains of John Follin were moved from Falls Church, Virginia to Arlington Cemetery. Follin is the only Continental Navy sailor to be honored with burial at Arlington. After a three-day chase, a British man-of-war captured the seventeen-year-old Follin. He was held captive in Plymouth, England and Gibraltar for three years.[5] At the war’s end Follin made his way back to Virginia where he spent the rest of his life farming.[6]

The grave of the most accomplished warrior among the Revolutionary veterans in Arlington, the last soldier re-interred in Arlington, is the only government-issue grave marker at this stop. Commissioned a colonel in 1776 and later brevetted to brigadier general, William Russell served with distinction until the end of the war. He commanded regiments at the battles of Brandywine, Germantown and Monmouth. His proficient leadership in the battle of Germantown earned high acclaim. Maj. Gen. Adam Stephens wrote Washington, “Col. Lewis and Col. Russell of Gen. Greene’s division … behaved gallantly during the action.”[7] After that battle, Washington entrusted Russell with sensitive command positions such as a leadership position at Fort Mifflin, a role in the storming of Stony Point and a mission to the Virginia frontier to provide troops for the Continental Army even in the face of attacks from Native Americans. After witnessing the British surrender at Yorktown, Russell returned home and his neighbors rewarded his service by naming Russell County, Virginia in his honor.[8] He is the oldest (in terms of birth year) person buried at Arlington.

The remaining five soldiers at this stop were reinterred from a degenerating, noxious Presbyterian cemetery in the Georgetown neighborhood of Washington, DC during the period 1892 to 1907. Two of these five Revolutionary veterans, James House and Thomas Meason, have “general” inscribed on their grave markers but neither served as a battlefield general in the Revolutionary War. In fact, they served much lower in the ranks.

James House is remembered with an obelisk-shaped white grave marker. A Virginian, he served as a matross (an artillery soldier who ranked below gunner) in the 1st Artillery Regiment.[9] He received a brevet brigadier-general’s rank in the peacetime army after the War of 1812.[10]

The grave markers for Thomas Meason, William Ward Burrows, Caleb Swan and Joseph Carleton are all well-worn, flat slab stones flush with the ground. Thomas Meason (or Mason in some sources) served as a sergeant in Darr’s Detachment of Pennsylvania troops.[11]

The Revolutionary War veteran with the most respected post-Revolution military role is William Ward Burrows who likely served during the Revolution in the South Carolina militia. The specifics of his Revolutionary War service including rank and military unit are uncertain. The most authoritative source suggests that his duties were of a secretive nature.[12] However opaque Burrows’s military record, his war service was sufficient to be accepted into the Society of the Cincinnati.[13] In the eyes of United States military history, Burrows became prominent when in 1798 the administration of John Adams appointed him the first commandant of the reconstituted Marine Corps. Burrows’ grave marker, however, is a cracked flat stone slab with fading remnants of a popular epitaph scripted to comfort those he left behind.[14]

Caleb Swan served as a corporal in the 9th Massachusetts Regiment and an ensign in the 3rd and 8th Massachusetts Regiments from 1777 to the end of the war. He suffered the harsh winter at Valley Forge and posted at both White Plains and West Point. Swan must have been a good soldier and enjoyed military life as he stayed on to serve in Jackson’s Continental Regiment after the rest of the Continental Army was disbanded. In 1792, he was named a paymaster in the army and served until 1808.

Born in Belvedere, England, Joseph Carleton served as a paymaster in Pulaski’s Legion during 1778 and 1779. The Continental Congress recognized Carleton’s administrative talents, electing him Secretary to the Board of Ordnance and Paymaster to the Board of War and Ordnance on October 27, 1779. Reorganizing, Congress elected Carleton to Secretary to the Board of War on February 17, 1781, a capacity in which he served through March 24, 1785.[15]

Before leaving this stop, walk across Humphrey Drive to the Lexington Minuteman commemorative plaque and memorial eastern hemlock tree. Dedicated in June 2000, the Lexington memorial is a small, rectangular plaque with the names of the eight minutemen who died on Lexington Green in the opening shots of the Revolutionary War. The Lexington Minute Men, a modern day reenactment organization, contributed this memorial plaque and tree.

Stop 3 – John Green’s Grave Site (Section 1-503)

Continue west on Humphrey’s Drive and arrive at the gravesite of John Green, a colonel in the 1st Virginia Regiment. Green fought at the battles of Mamaroneck, NY (where he was wounded), Brandywine and Monmouth. Given his effective battlefield leadership, Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Greene ordered Green’s unit held in reserve to cover an anticipated retreat at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse. Green chaffed at this assignment, but it demonstrated the confidence Maj. Gen. Greene had in John Green’s military leadership and fighting prowess.[16]

In 1935, Green’s remains were transported from his home at Liberty Hall in Culpeper County, VA, to Arlington.

Stop 4 – James McCubbin Lingan’s Grave Site (Section 1-89A)

Continuing on Humphrey’s Drive to the end, turn right on Meigs Drive and walk a few minutes to the grave site of the next Revolutionary soldier to be re-interred at Arlington. Commissioned as 2nd lieutenant in the Maryland and Virginia Rifle Regiment in July 1776, Lingan fought in the Battle of Long Island. Wounded and taken prisoner at the November 16, 1776 surrender of Fort Washington, he spent three and one half years on the infamous prison hulk Jersey and on parole on Long Island.[17] Upon exchange Lingan received a promotion to captain in Rawling’s Additional Continental Regiment. He retired on January 1, 1781.

After the Revolution, he garnered the honorific title of general. Lingan is notable for defending the freedom of speech and freedom of the press during the War of 1812. A Baltimore mob incensed by anti-war editorials attacked the offices of the Federal Republican and Commercial Gazette. To protect free speech and the right of dissent, Lingan openly defied the mob, which beat him to death. Initially buried in a private cemetery in Washington, DC, Lingan’s remains were moved to Arlington Cemetery on November 5, 1908.

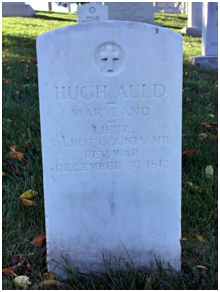

Stop 5 – Hugh Auld’s Grave Site (Section 2- 4801)

Re-trace your steps back on Meigs Drive and turn right on Sheridan Drive (at the Tanner Amphitheater). At the first bend in the path is the last stop at the grave of Hugh Auld who in 1935 was re-interred in Arlington from a family plot in Claybourne, Maryland. Unremarkably, Auld served as lieutenant in the Maryland Talbot County militia under the command of Capt. Thomas Hopkins. He may not have even received a formal commission.[18] However, the most interesting facet of Auld’s life is that his brother owned Frederick Douglass and lent him to Hugh Auld as a house slave. Eventually, Hugh Auld assisted Douglass in gaining employment in a Baltimore shipyard and aided his to escape to the north and freedom.[19]

On your way back to the visitors’ center, contemplate the contributions of other Revolutionary War veterans groups not represented at Arlington Cemetery. In 2009, a special Arlington ceremony bestowed military honors on Oscar Marion, an African American Patriot. Marion, the personal slave of the famous “Swamp Fox” Francis Marion, fought in the Revolution alongside his master. The character Occam in the movie The Patriot is fashioned after Oscar. Oscar’s remains are likely buried on a South Carolina plantation; the Arlington ceremony partially recognizes the contributions of African Americans in gaining the nation’s independence.[20]

Even though these eleven veterans represent a small fraction of those who participated in the fight for independence, they epitomize the range of experiences of Revolutionary War soldiers. There are accomplished warriors such as William Russell, and those such as James House of whose contributions we know little. There are notable people such as Pierre L’Enfant and those who are lost to history such as John Follin. There are those that continued in their military career after the Revolution such as William Ward Burrows and those that went onto successful business careers such as Thomas Meason. And finally there are those such as James McCubbin Lingan who continued to fight and die for our rights and freedoms.

Next time you are at Arlington Cemetery, visit the gravesites of these eleven Revolutionary War veterans to recognize their military service and reflect upon the contributions of the other 250,000 soldiers who fought for our independence.[21]

[1] L’Enfant’s captain’s commission was backdated to February 18, 1779 for seniority purposes.

[2] Lafayette to Comte de Vergennes, December 16, 1783, in Stanley J. Idzerda and Robert Rhodes Crout, ed. Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution, Selected Letters and Papers, 1776-1790 (Ithaca, NY and London: Cornell University Press, 1983), 5:176-8.

[3] http://www.arlingtoncemetery.mil/Explore/Notable-Graves/Prominent-Military-Figures/Pierre-Charles-LEnfant, accessed October 25, 2016.

[4] Robert M. Poole, On Hallowed Ground: The Story of Arlington National Cemetery (New York: Walker & Company, 2009), 123.

[5] Sheldon Marvin Ely, The District of Columbia in the American Revolution and the Patriots of the Revolutionary Period who are interred in the District or Arlington Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Volume 21 (Lancaster, PA, New Era Publishing Company, 1918), 135.

[6] Cynthia Parzych, Historical Tours Arlington National Cemetery (Guilford, CT: Rowman & Littlefield, 2015), 42-3.

[7] Philander D. Chase and Edward G. Lengel, eds., The Papers of George Washington: Revolutionary War Series, Volume 11 (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2001), 468.

[8] Anna Russell Des Cognets, William Russell and His Descendants (Lexington, Kentucky: Printed for the family by Samuel F. Wilson, 1884), 14.

[9] Sheldon Marvin Ely, The District of Columbia in the American Revolution, 134.

[10] John Ball Osborne, The Story of Arlington: A History and Description of the Estate and National Cemetery (Washington, DC: published by the author, 1899), 33.

[11] Sheldon Marvin Ely, The District of Columbia in the American Revolution, 134.

[12] Rosa Baylor Hall, Revolutionary War Patriots and Soldiers: Thomas Bond, 1713-1784; William Ward Burrows, 1758-1805; Roger Nelson, 1759-1815; a genealogical history with biographical sketches (Compiled and Self-published, 2003), 131.

[13] Bryce Metcalfe, Original Members and Other Officers Eligible to the Society of Cincinnati, 1783-1938 (Shenandoah Publishing House, 1938), 350.

[14] “His death (and such, Oh reader wish thy own)

Was free from terrors and with a grown

His spirit to himself the almighty drew

Mild as his sun exhales the ascending dew”

[15] Thomas H. S. Hamersley, Complete Army Register of the United States for 100 Years (Washington, DC: Thomas H. S. Hamersley, 1881), 233.

[16] http://www.arlingtoncemetery.net/j-green.htm , accessed October 25, 2016 and John Buchanan, The Road to Guilford Courthouse: The American Revolution in the Carolinas (New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1997).

[17] Revolutionary War Service Records, accessed via www. Fold3.com, https://www.fold3.com/image/11926824/?terms=James%20McCubbin%20Lingan, accessed November 11, 2015.

[18] S. Eugene Clements and Edward F. Wright, The Maryland Militia in the Revolutionary War (Silver Springs, MD: Family Line Publications, 1987), 233.

[19] : http://soldiers.dodlive.mil/2014/06/theres-a-lot-you-dont-know-about-arlington-national-cemetery/#sthash.SkGZSHsL.dpuf, accessed October 25, 2015

[20] James Hohmann, “A Patriot History Almost Forgot,” Washington Post, October 11, 2009.

[21] A listing of marker locations for those interesting in visiting the Revolutionary Soldiers gravesites:

| Stop | Name | State | Internment Date | Section |

| 1 | Pierre Charles L’Enfant | FR | April 28, 1909 | 2-S 3 |

| 2 | William Russell | VA | July 17, 1943 | 1-314 A |

| 2 | Thomas Meason | PA | May 12, 1892 | 1-297 B |

| 2 | John Follin | May 23, 1911 | 1-295 1/2 | |

| 2 | William Ward Burrows | SC | May 12, 1892 | 1-301 B |

| 2 | Esq. Caleb Swan | MA | May 12, 1892 | 1-301 C |

| 2 | Joseph Carleton | November 13, 1907 | 1-299 | |

| 2 | James House | VA | May 12, 1892 | 1-297 A |

| 3 | John Green | VA | April 23, 1931 | 1-503 |

| 4 | James McCubbin Lingan | MD | November 5, 1908 | 1-89 A |

| 5 | Hugh Auld | MD | April 11, 1935 | 2-4801 |

13 Comments

Gene – thank you for your beautiful article and photos. I hope it becomes the premiere guide for any Revolutionary War enthusiasts visiting this most sacred of our national cemeteries. I never knew the story about Oscar Marion either, so thank you; and I’m glad he and other brave African-Americans were certainly recognized in the ceremony.

My father, John L. Smith, a three-time decorated Korean War veteran is buried at Arlington as well. Your article is a wonderful guide for all Patriots.

John, it is clear why Arlington Cemetery is a special place for you. As a nation, it is great that we have a place to remember those on whose shoulders we stand. Thank you for your comments.

Gene, thanks for this informative (and informed) piece. Nicely done. I’ll make sure and consult it the next time I get to DC and Arlington National Cemetery. I did not know this history; actually surprised me to learn some Revolutionary era soldiers were buried there.

This is an excellent article. I am impressed that there are some revolutionary soldiers buried at Arlington Cemetary. This is amazing original research to uncover this. Are there any loyalists buried in England?

Thank you Carol for your comments. When the British army left, they also, evacuated many American Loyalists who were taken to Canada, Florida, the Caribbean and to Britian. So there are American Loyalists buried in Britain and throughout the world.

Just to add for those who don’t know the history… Robert E. Lee’s father and the great Revolutionary War hero, Light Horse Harry Lee, was injured in the Baltimore mob riot that killed Lingan. Light Horse Harry tried to defend him, and was injured in the effort. Given the circumstances of the appropriation of the Custis-Lee property, I find Lingan’s reinterment both lovely and ironic. Thanks for the information!

I think your article is very good and helps to point to Arlington Cemetery’s importance. I did my own research on this group of soldiers (and one sailor) last summer and developed a two hour walking tour which I have led several times. I call it “The Legacy of George Washington and the Revolutionary War at Arlington National Cemetery” My investigation points to the exact same conclusions that you presented here except on one account.

I found three generations of Hugh Aulds connected to each other which I think leads to the confusion. The Revolutionary War Talbot County militiaman died in 1813, 5 years before Frederick Douglass was born. His nephew, Hugh Auld was who is buried right next to him at Arlington was in the Maryland Militia in the war of 1812 and died in 1820. He was the father of Hugh and Thomas Auld who I think were the actual owners of Douglass. That third-generation Hugh Auld (not buried at Arlington) accepted 150 pounds sterling from Douglass’s British supporters in 1846 for his freedom. I think that the Revolutionary War militiaman was the great uncle of the owners of Douglass. So besides my one small quibble, I think an excellent explanation on a much overlooked aspect of the cemetery.

Thank you Harry for your feedback and for correcting the Auld-Douglass relationships by untangling the three generations of Hugh Auld. Arlington is a special place with many mysteries and interesting facts yet to be discovered. Your interpretive walk sounds interesting and I bet you will find many willing participants among the JAR readers!

Can you help with a little curiousity? Why or whom Is Humphreys Drive named after?

Thanks!

My best guess for who Humphreys Drive was named after was General David Humphreys, a close revolutionary brother-in-arms to General George Washington.

Andrew A. Humphreys was a Civil War General whom Ft. Belvoir, VA was originally named.

This is a good question. I’ve looked at lots of websites and books, but I can’t find an authoritative answer. I think it must be named for Andrew A. Humphreys who was made a Union Maj. Gen. during the Civil War. His leadership as a corps commander for the Union Army at Gettysburg is considered significant and he is honored with a statue on the battlefield. Before the war he had worked for ten years on a scientific analysis of the Mississippi River Delta trying to understand the flooding and water depths. He was the Chief Engineer of the Army after the war. Humphreys Peak (the tallest in Arizona) is also named for him. His grandfather, Joshua Humphreys was a naval architect who designed six frigates for the US Navy in the 1790’s, including the USS Constitution.

Well done article.

I am a SAR and just visited Arlington.

I did not have your info.

Of interest to me is that there are 1000s of Revolutionary War soldiers and sailors interred in various cemeteries in the US and elsewhere.

Is there any momentum to re allocate these heroes to Arlington?

John Auld

Thanks John. I don’t believe there are any efforts underway to move Revolutionary veterans to Arlington. National cemeteries were not in existence during or after the Revolution. Many Revolutionary War soldiers are buried in unmarked graves where they fell on the field of battle or died in a cantonment. Others that passed after the war are buried in town or church cemeteries. These eleven Revolutionary War vets are buried at Arlington due to luck of the draw and not for any premeditated reason.

Are you related to Hugh Auld who was reinterred in 1935 at Arlington?