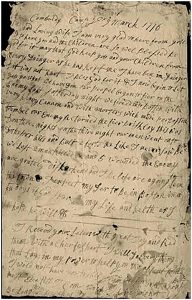

There isn’t a doubt that Oliver Reed was just like any other soldier who had gone away to fight in the American Revolution, writing home to his wife and four young children in Pomfret, Connecticut as he was stationed many miles away in New York during April 1776. “I want to se you very much But Cant at present But my hert is With you al tho we are at [gre]at Distence from one a nother But the time I hope will Com when we shall se one another faces again in pece and safety so no more my Der at this time But will Rite to you again as soon as possabel”[1]. In 2014, a descendent of Oliver Reed came to the David Library in Washington Crossing, Pennsylvania, with a stack of letters that had been a part of his family for several generations. Written between 1776 and 1779, the letters began to piece together a story of an everyday soldier who had been off fighting in the War of Independence just as his wife was facing great difficulties at home.

Born on April 11, 1746 at Attleborough, Massachusetts, to Ichabod Read and Elizabeth Chaffe, Oliver married Betty Force of nearby Wrentham. By 1771, the couple had moved to the small town of Pomfret, Connecticut, where they soon had their four children.[2] Oliver’s military career began in 1775 when he served for twelve days at Lexington before the formation of Gen. Israel Putnam’s Third Regiment in May 1775. By 1776, the regiment was reorganized as the 20th Continental under Col. Benedict Arnold and eventually Col. John Durkee, under which Oliver became Sergeant Reed.[3] It’s during this time when the first letters of the collection were written in Cambridge, Massachusetts, just as General Washington gave the commands for the first regiments to march to New York.[4] “we are agoing to march from this place in a fu days But whare We no not yet sum say to new yourk”[5]

General Washington was readily prepared when it was suspected that the British were planning to move towards New York, not willing to take any chances of a British occupation. When Gen. Charles Lee passed the warning to Congress that an invasion was imminent, preparations were made along the Hudson. Lookout was prepared to give the warning of British fleet in Long Island Sound and numerous regiments were sent to secure the area.[6] Battery sites were built along the Hudson River and New York harbor, with a prominent location being Paulus Hook, New Jersey. For a few months, Oliver remained in New York before heading to Paulus Hook during the Battle of Long Island.

Never failing to write home to his family, Oliver began to face some hardships whilst away. Illness was constant and Oliver fell ill numerous times, but kept a lighthearted spirit about it when he wrote on May 5, “I must tel you sumthing that I Beleve will make you Lafe I have Drank sum tee sence I have Ben sik and it so good that I Could not help By sum for you and I have sent you a half a pound of good tee and hope it will do you a grate del of good.”[7] Dreaming of his wife’s pickles and cold meats, there was unsurprisingly a great desire to return home to his family and constant planning to return home soon.

Before long, Oliver was writing from Paulus Hook as the 20th Continental was stationed along the New Jersey shore. Now a neighborhood in Jersey City, Paulus Hook had been a prominent landing place in connection to New York. Established as one of several battery sites along the Hudson with the intention of preventing the British fleet from sailing into New York, Paulus Hook was relentlessly defended and saw action twice in July 1776.[8] Despite being ill for the duration, Oliver was able to relate back to his wife the failures and details of the Battle of Long Island.

and as to News I have But Littel to Right But will give you a short account of the Battel on Long Island the Enemy Landed on the Island on the 24 of August on the 27 Day at 2 a Clock in the morning the Battel begun and Lasted till the 29 day at night and then our peopel Left the Island and Came over to york and now our army is to gather wich is much Better then it was when it was Devideed the Loss on our side is not yet none But By what I Can Lern it tis not Les then one thoushand Killed and taken prisoners the Enemys Los By the Best accounts that the Genrel Can get is 3 to one killed and not so maney taken the 27 and 28 days was the hottes of the Fight our men stood thair ground Like men and fet Like herose I was not on the Island my self But I se them that ware in the acshon and thay told me the Enemy Came up to the Lines 3 times and our men made them Retreet Back for the grape that cut lanes through them.[9]

Oliver’s letters come to a long gap, and while it is uncertain where he was until his next letter placed him in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, the 20th Continental Regiment continued to have an active role. After the loss at Long Island forced Washington’s troops into New Jersey, Colonel Durkee’s regiment was present on the banks of the Delaware in 1776[10] and at the battles of Trenton and Princeton as part of Brig. Gen. Hugh Mercer’s Brigade. Colonel Durkee himself was been injured at the Battle of Princeton.[11] The 20th Continental Regiment was once again reorganized in January 1777 as the 4th Connecticut Regiment, and two companies under Colonel Durkee were sent to harass the British along the Raritan River in Bound Brook and Raritan, New Jersey.[12] By March, Colonel Durkee’s regiment was part of the first two brigades sent to Peekskill, New York, to help reinforce General Putnam who had taken over command in there. While no letters survive from Oliver there, service cards show that he was present at the location between July and September 1777.[13]

Up until this point, Betty was alone raising their four children, Nabby, Oliver, Chester and Betsey. The family had little and required help from neighbors, especially during the winter months. At one point, Betty had to move the children to a new home for reasons unknown. Money was certainly an issue the family faced and Oliver made it clear how much he wished he had enough to send home to the family. In her only surviving letter to Oliver in August 1777, Betty wrote that tragedy struck home. Two of their children, Nabby (born October 14, 1771) and Chester (born November 16, 1774) died. Their youngest daughter Betsey, who would die shortly after her first birthday in September, was described as being ill when her siblings passed away.[14]

Chester was Extrem Bad with the camp ale and the putred fever Set in pore litel Creatre he was very Bad in Deed But pacent as a Lam he made no complant only mome I am tired I am tired But pore Child I hope he is gon to Rest in the armes of Jisus

On the 18 Day a bought Sun Rise he semed to Be Struck with Deth But he Lived til the 19 jest sun down I never See no Body dy in such Destress as he Did he had his Sences till the Last and the Last words he Said was I am a Coming I am a Coming I am a Coming and Reached his Litel hands as hi as he Could oh how hard it was to part with my child But I hop he is gone to Rest

“altho neighbours ware kind around me yet there was no father to help and pity them.” Betty continued, expressing the pain she felt at the death of her children without Oliver to be there: “My Dr I hope you will Do your utmost to come home soon for my troubel and Destress is so great that I would give all the world for my nerest frind to comfort me.”[15] Unfortunately for Oliver, he had been ill at the time in Peekskill,[16] too far away to be able to return home to comfort his wife in such horrific times.

Without her husband at home to support her, Betty had up to this point relied on help from her neighbors and friends in Pomfret. As winter approached, she was left alone with only one surviving child while her husband was in Valley Forge. Betty had nothing else to do but move to her hometown of Wrentham to live with Oliver’s parents, as he expressed in a letter written home in January 1778: “I Desier to Return you my Herty thanks For your Ciness to my wife & son in takeing them hom With you this winter I hope that I shall be a bel to pay all [cut off] trobel you are at & am willing to Do it if I Live to Return as it hath Plesed the Almity God in the womb of his Devine Provadense to take From us our Children Let us not murmer nor Complayn.”

Oliver felt guilty about having to burden his parents, but his family had little and he was far away being exposed to small pox and watching his fellow men go off to live in caves as the winter progressed. Just the previous month, he had witnessed the death of his captain, Stephan Brown: “he was Wounded in Mud Fort with a musquete Ball From the ship he was Shot into one side of the neck the Ball Lodg in his Body he Lived 24 ours and died.” Oliver almost seemed envious of Brown, stating he was now free from all trouble, no longer hearing the sound of soldiers or seeing the “garments rolled up in blood” while Oliver was requesting more shirts from his family. Up until this point it’s uncertain just how much religion had an impact in Oliver’s life, but as he had done in previous letters he spoke of the afterlife as being free from such troubles as he had been witnessing and the deaths of his children. Unsure whether he would see his parents and family, he said, “God grant that we may Live to mett again in this World: if not tis my Desier and Prayers to god that we may met in the Heavenly World whare thare is no more Deth: neither sound of the woryer nor garments Rold in Blood.”[17]

In the upcoming months, Oliver would go on furlough while his regiment eventually made its way to White Plains, New York. We see no more letters from Oliver, who according to service cards was sick at Norwalk, Connecticut, from July to September 1778.[18] Previously, a hospital had been on location in Norwalk under William Eustis housing 700 patients from fall 1776 until March 1777.[19]

Oliver Reed died on October 21, 1778[20] after his long stay at Norwalk and was officially “supposed dead” by the military in November.[21] In the final letter in the collection, Betty wrote to his family to express her grief after losing her husband: “your Brother who was a part of you Bone of your bone and flesh of your flesh is gon and is no more among the Living but is Congregated with the Dead Sufer me your unworthy Sister to Speak a word in your Ear be ye all so Ready Becawse there is wrath beware Lest he take you away with a strock for the feet of him that Caried away your Brother that is the mesanger Death.”[22] Just a year before, Betty lost three of her children and was now a widow with a five-year-old son to take care of. She would soon remarry in November 1784 to Samuel Bugbee;[23] they had a son named Chester as mentioned by the young Oliver Reed Jr. in a letter written in 1788 from New London, Connecticut.[24] The marriage ended in divorce in 1788. Betty Reed died in 1821.[25]

Oliver Reed was just one of thousands who served in the American Revolution. While his life was tragically cut short at thirty-three, he is remembered through his letters that have survived in his family for nearly two hundred and fifty years. They allow us to take a further look into the life of a soldier not unlike many others, as he got sick, fought in battles and constantly thought about his family back home. Betty left only one letter, but the correspondence with her husband gave a look at just how much she went through as she tried to take care of her children and home singlehandedly.

[1] Oliver Reed (OR) to Betty Reed (BR), New York, April 30, 1776. Oliver Reed Letters, David Library Digital Archives, David Library of the American Revolution, Washington Crossing, PA.

[2] Connecticut Town Birth Records, pre-1780 (Barbour Collection). Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com, Operations Inc, 2006.

[3] Connecticut. Adjutant-General’s Office. The Record of Connecticut Men of the Military and Naval Service During the War of the Revolution 1775-1783 (Baltimore, MD.: Clearfield Company, Inc., 1997), 53-54.

[4] W. W. Abbot and Dorothy Twohig, The Papers of George Washington Confederation Series (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1992-1997), 3:516-517.

[5] OR to BR, Cambridge, MA, March 20, 1776.

[6] Eric Manders, The Battle of Long Island (Monmouth Beach, N.J.: Philip Freneau Press, 1978), 10–13.

[7] OR to BR, New York, May 5, 1776.

[8] Barnet Schecter, The Battle for New York: The City at the Heart of the American Revolution (New York: Walker & Co., 2002), 85-87, 182.

[9] OR to BR, Paulus Hook, NJ, September 4, 1776

[10] Charles H. Lesser, The Sinews of Independence: Monthly Strength Reports of the Continental Army (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1976), 43.

[11] William S. Stryker, The Battles of Trenton and Princeton (Spartanburg, SC: Reprint Co., 1967), 379.

[12] Abbot and Twohig. The Papers of George Washington Confederation Series. 8:268.

[13] Compiled Service Records of Soldiers Who Served in the American Army During the Revolutionary War. National Archives Trust Fund Board: Washington, 1976. David Library of the American Revolution Film 46.

[14] Barbour Collection.

[15] BR to OR, Pomfret, August 31, 1777.

[16] Compiled Service Records. David Library of the American Revolution Film 46.

[17] OR to BR, Valley Forge, January 8, 1777.

[18] Compiled Service Records. David Library of the American Revolution Film 46.

[19] M. C. Gillett, The Army Medical Department, 1775-1818 (Washington, DC: Center of Military History, United States Army, 1981), 72-76.

[20] Barbour Collection.

[21] Compiled Service Records. David Library of the American Revolution Film 46.

[22] BR to family, Wrentham, October 27, 1778

[23] Barbour Collection.

[24] OR [Jr.] to BR, New London, 1788.

[25] Thomas W. Baldwin, Vital Records of Wrentham Massachusetts, To The Year 1850. Volume 3- Death Records. (Boston, MA: New England Historic and Genealogical Society, 1901), 418.

One thought on “Oliver Reed: Letters of an American Soldier”

What a heart wrenching story! Distance, travel mode and limited communication made long separations from loved ones extraordinarily difficult for 18th c. people. It is hard to imagine their suffering given modern life with all of it`s travel and communication conveniences. Your article excellently conveys the sense of hardship and despair evident in the lives of the Reed family. I would think that these tragic circumstances were experienced by many other families during The American Revolution. Thanks for a very interesting article.

John Pearson