Among other communicable diseases, the itch was common in military installations of the eighteenth century. Unlike smallpox and typhus, the itch was not in itself fatal, but was stressful and debilitating to soldiers and sailors on both sides of the conflict in the American Revolution. Today the distressing malady is known as scabies, “a disease caused by an infestation by the itch mite, Sarcoptes scabiei, var. homini.”[1] The itch was thoroughly described by William Buchan as early as 1769.

[The] disease is commonIy communicated by infection, yet it seldom prevails where due regard is paid to cleanliness, fresh air, and wholesome diet. It generally appears in form of small watery pustules, first about the wrists, or between the fingers; afterwards it affects the arms, legs, thighs, &c. These pustules are attended with an intolerable itching, especially when the patient is warm a-bed, or sits by the fire. Sometimes indeed the skin is covered with large blotches or scabs, and at other times with a white scurf, or scaly eruption. This last is called the dry itch, and is the most difficult to cure.[2]

As described by Alexander Gordon before 1800, the itch “may affect any part of the body but principally the Interstices of the fingers, the insides of the Wrists, the hands, and the sides of the belly.”[3]

The itch was well-known to Continental army officers and soldiers alike. Citing Fitzpatrick[4] in general, the U. S. Army Medical Department, Office of Medical History relates that, within the papers of George Washington,

there are hundreds of references to military health precautions, cleanliness broadly conceived, sanitation, policing of camps, huts and quarters, food (diets, rations, and “the proper dressing” of provisions), clothing, hospitals and The Hospital, inoculation for smallpox, sulfur ointment for inunction for the itch (scabies), and a great variety of hygienic matters-all attesting to Washington’s personal interest in doing everything he knew how to do to preserve the health of the troops.[5]

While at Valley Forge, General Washington was well aware of the prevalence of the itch, and issued a general order on January 8, 1778: “Being also informed many men are rendered unfit for duty by the itch, He [the Commander -in-Chief] orders and directs the Regimental Surgeons to look attentively into this matter and as soon as the men who are affected with this disorder are properly disposed in Hutts to have them anointed for it.”[6]

Private soldier Joseph Plumb Martin, stationed at Peekskill in 1778, recounted his experience with the disease, and described the extent of debilitation brought about by that ailment.

When I was inoculated with the smallpox I took that delectable disease, the itch; it was given us, we supposed, in the infection. We had no opportunity, or, at least, we had nothing to cure ourselves with during the whole season. All who had the smallpox at Peekskill had it. We often applied to our officers for assistance to clear ourselves from it, but all we could get was, “Bear it as patiently as you can, when we get into winter quarters you will have leisure and means to rid yourselves of it.” I had it to such a degree that by the time I got into winter quarters I could scarcely lift my hands to my head.[7]

It may have been widely known that the application of sulfur concoctions to the flesh afflicted with the itch afforded relief, for Dr. Buchan had written “the best medicine yet known for the itch is sulphur, which ought to be used both externally and internally. The parts most affected may be rubbed with an ointment made of the flowers of sulphur, two ounces; crude sal ammoniac finely powdered two drachms; hog’s lard, or butter, four ounces.”[8] As mentioned, General Washington ordered the use of sulfur ointment for the itch. Powdered sulfur, or sulfur flowers, was in great demand for the manufacture of gunpowder, and may not have been freely available for the preparation of topical medicaments. Joseph Plumb Martin was fortunate to have comrades who had friends among the artillerymen of his regiment, and through that association was able to find precious sulfur: “Some of our foraging party had acquaintances in the artillery and by their means we procured sulphur enough to cure all that belonged to our detachment. Accordingly, we made preparations for a general attack upon it.”[9]

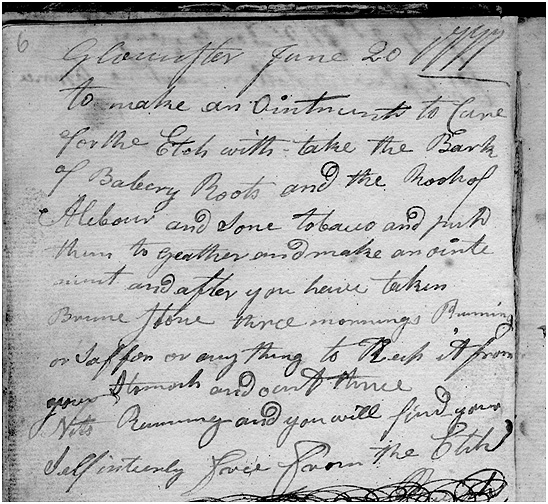

In 2013 a document was uncovered at The David Library of the American Revolution which signifies the particular importance relief from the itch had among American soldiers in 1777. The document, bound within an orderly book, is dated 1777 at “Gloucester” [Glocester], Rhode Island and relates a recipe “for to cure for the Etch.” This was deemed by the unknown author to be important enough to be recorded among the military orders which fill most all other pages of the book.

A formulation “For to Cure for the Etch.” Detail from a page from the Capt. Asa Kimball Orderly Book Collection.[10]

Glouster June 20 1777

to make an Ointmint to Cure for the Etch with take the Bark of Babery [bayberry] Roots and the Root of Hibocis [hibiscus] and Some tobacco and put them to geather and make an ointe mint and after you have taken Brime Stone three mornings Running or Saffon [saffron] or anything to Keep it from your Stomach and oint three Nits Running and you will find your Self intierly free from the Etch

For to Cure for the Etch

“The Cure” is an innovative combination of ingredients. Bayberry[11] was recognized early on as a source for medicines, and Nicholas Culpeper, quoting the ancient Greek physician Galen, related “that the leaves or bark do dry and heal very much,” and added that “The oil takes away the marks of the skin and flesh by bruises, falls, &c. and dissolveth the congealed blood in them: It helpeth also the itch, scabs, and weals in the skin.”[12]

The swamp rose mallow, Hibiscus moscheutos, grew wild in the wetlands of New England, and may have been the plant the author referred to. Although the 1777 author may not have been aware of the specific medicinal value of the components of hibiscus root, it may have been known as a natural emollient or as a treatment for dermatologic disorders in the folklore of the day.[13] Recent work suggests its incorporation into the medicament may have imparted a valuable therapeutic function.[14]

The addition of tobacco, while questionable by twenty-first century standards, may have been sensible to the author of “the Cure”, as the topical application tobacco has been shown to have been successfully used in treatment of “bites of poisonous reptiles and insects; hysteria; pain, neuralgia; laryngeal spasm; gout; growth of hair; tetanus; ringworm; rodent ulcer; ulcers; wounds; respiratory stimulant” in a modern survey of fifteenth- to nineteenth-century medicine.[15]

The author of “the Cure”, like many of his contemporaries, was clearly aware of the value of sulfur and saffron in combatting the itch. He instructs to apply “Brim Stone” or “Saffon” to retard the spread of infestation to the abdomen from the extremities (“or anything to Keep it from your Stomach”). Saffron had been known from antiquity for its medicinal value. Culpeper wrote:

It helps consumptions of the lungs, and difficulty of breathing. It is excellent in epidemical diseases, as pestilence, small-pox, and measles. It is a notable expulsive medicine, and a notable remedy for the yellow jaundice. My opinion is, (but I have no author for it) that hermodactyls[16] are nothing else but the roots of Saffron dried; and my reason is, that the roots of all crocus, both white and yellow, purge phlegm as hermodactyls do; and if you please to dry the roots of any crocus, neither your eyes nor your taste shall distinguish them from hermodactyls.[17]

“The Cure” instructs to prepare for the application of the novel “ointe mint” by plying sulfur or saffron to affected areas three mornings in a row, presumably as ointment or paste. Only then should the concoction of bayberry, hibiscus, and tobacco be applied, explicitly “three Nits running.” This interesting combination therapy regimen with specific morning and evening schedules promises “you will find your Self intirely free from the Etch!”

Joseph Plumb Martin and his unit practiced their own combination therapy to combat the itch. Their cure also involved topical sulfur application, but included an assault on the “animalcule of the itch” from within: the oral administration of a whiskey-based formulation.

The first night one half of the party commenced the action by mixing a sufficient quantity of brimstone and tallow, which was the only grease we could get, at the same time not forgetting to mix a plenty of hot whiskey toddy, making up a hot blazing fire and laying down an oxhide upon the hearth. Thus prepared with arms and ammunition, we began the operation by plying each other’s outsides with brimstone and tallow and the inside with hot whiskey sling. Had the animalcule of the itch been endowed with reason they would have quit their entrenchments and taken care of themselves when we had made such a formidable attack upon them, but as it was we had to engage, arms in hand and we obtained a complete victory, though it had like to have cost some of us our lives. Two of the assailants were so overcome, not by the enemy, but by their too great exertions in the action, that they lay all night naked upon the field. The rest of us got to our berths somehow, as well as we could; but we killed the itch and we were satisfied, for it had almost killed us. This was a decisive victory, the only one we had achieved lately. The next night the other half of our men took their turn, but, taking warning by our mishaps, they conducted their part of the battle with comparatively little trouble or danger to what we had experienced on our part.[18]

[1] Robert H. Gates, Infectious Disease Secrets: Questions and Answers Reveal the Secrets to the Diagnosis and Management of Infectious Diseases, 2nd Ed. (Philadelphia: Hanley & Belfus, Inc., 2003), 355.

[2] William Buchan, Domestic Medicine, 1785 Edition. Chapter XXXIX, “THE ITCH.” eBook edition accessed at http://www.americanrevolution.org.

[3] Alexander Gordon, The Practice of Physick by Alexander Gordon: On Being a Physician – and a Patient – in the 18th Century, ed. Peter Bennett. Google eBook edition; 313.

[4] John C. Fitzpatrick, ed. The Writings of George Washington From the Original Manuscript Sources, 1745-1799. 39 vols.; 37 text and 2 index. (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1931-1944).

[5] From the U. S. Army Medical Department Website, http://history.amedd.army.mil. Page 33.

[6] George Weedon, Valley Forge Orderly Book of General George Weedon of the Continental Army Under Command of Genl George Washington, in the Campaign of 1777-1778, etc. (New York: Dodd, Mead and Co., 1902; reprinted 1971 by Arno Press): 186.

[7] Joseph Plumb Martin, Private Yankee Doodle; Being a Narrative of Some of the Adventures, Dangers and Sufferings of a Revolutionary Soldier. ed. George F. Scheer, (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1962), 110.

[8] Buchan, Domestic Medicine, “THE ITCH.”

[9] Martin, Private Yankee Doodle, 110.

[10] Source: The image is contained in the Capt Asa Kimball Orderly Book 1776 Collection in the David Library of the American Revolution Digital Archive (Washington Crossing, PA) and is used with permission. The provenance of the Asa Kimball Orderly Book is unknown. The bound volume (21 cm x 14 cm) was placed on temporary loan to the David Library in 2013 by a private collector. The digital collection was prepared by the David Library.

[11] Common name for the Myricaceae family, synonymous with Bay Tree.

[12] Nicholas Culpeper, The English Physician Enlarged, With Three Hundred Sixty-Nine Medicines Made of English Herbs, That were not in any Impression until This, etc. (London: Printed for P. McQueen, J. Laikington, et al, 1788), Google Books edition, 30-31.

[13] The utility of Hibiscus species in alternative medicine therapy is discussed in Katherine Y. Kim, “Hibiscus,” in The Gale Encyclopedia of Alternative Medicine, Second Edition. ed. Jacqueline L. Longe, (Detroit: Thompson-Gale, 2005), 960.

[14] Ali, Badreldin H. et al, “Phytochemical, Pharmacological, and Toxicological Aspects of Hibiscus sabdariffa L.: A Review,” Phytotherapy Research 2005; 19:5, 369-375. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1628.

[15] G. G. Stewart, “A History of the Medicinal Use of Tobacco 1492-1860.” Medical History 1967; 11: 228-68. PMCID: PMC1079499.

[16] Johnathan Pereria, The Elements of Materia Medica and Therapeutics. Third American Edition, Enlarged and Improved by the Author. Including Notices of Most of the Medicinal Substances in Use in the Civilized World, and Forming an Encyclopaedia of Materia Medica. ed. Joseph Carson. (Philadelphia: Blanchard and Lea, 1854), 2:181. A hermodactyl is Colchicum spp. such as Autumn crocus or meadow saffron.

[17] Culpeper, The English Physician, 259.

[18] Martin, Private Yankee Doodle, 110-111.

3 Comments

Excellent article. Several years ago I sought, in vain, for material on this irritating topic but only scratched the surface (sorry, I couldn’t resist). You however have covered the itch story completely. Thank you for filling in this knowledge gap.

As a pediatrician in my professional life I have dealt with scabies often enough to find this article fascinating. Give that the ‘Cure for the Etch’ was written in Gloucester I ponder whether the author might have been Dr. Solomon Drowne, a botonist-physician who served as a surgeon’s mate in RI regiments during the Revolution between 1776 and 1783, and on whom I have written a biography at: http://gaspee.org/SolomonDrowneJr.html . Gloucester, RI and Foster, RI are adjoining towns. Unfortunately I have no examples of his handwriting with which to compare other than his assumed signatures (which do not match) below the images available at: http://www.riheritagehalloffame.org/inductees_detail.cfm?iid=430 and http://www.geni.com/people/Dr-Solomon-Drowne/5162683630450048079

It sounded to me as though this might have been a transcription into the orderly book by someone other than the originator of the recipe, John, so a handwriting comparison may not be particularly useful.

This is a fascinating article, and it highlights some of the many ways in which medicine and daily life were different during the time of the Revolution.