In the summer of 1774 when the 38th Regiment of Foot arrived in Boston harbor, amongst the 450 officers and men who disembarked were two trained artists – Joseph Dunkerley and Richard Brunton. While miniature painter Dunkerley’s history and accomplishments have been well documented, new details concerning engraver Brunton’s life and times and his artistic legacy are only now coming to light.

Although Brunton later claimed he was born in Birmingham, England in 1749,[1] no record of his birth or parents has yet been found. In 1766, he is listed as an apprentice to Joseph Troughton, a diesinker and engraver.[2] Birmingham at that time was a leading exporter of jewelry, plate, hardware, buckles, watches and chains to the colonies. At Troughton’s workshop, Brunton would have been taught how to do engravings, how to make metal dies (moulds) for stamping, and how to create raised impressions on coins, medals, and buttons. To be accepted as an apprentice in this craft required a high degree of eye and hand coordination as well as some innate artistic abilities. As it turned out, Brunton’s experience with this work was excellent preparation for making counterfeit paper currency and coinage from scratch.

On the first available muster rolls for his regiment, dated May 7 through December 1774, Brunton is listed as a private soldier in the grenadier company.[3] Because a year of experience in the army was required before assignment to this company, he must have enlisted no later than the early part of 1773. He would soon serve at the forefront of some of the bloodiest battles of the Revolutionary War, including the expedition to Concord, Massachusetts on April 19, 1775, the Battle of Bunker Hill in June of that year, the fierce campaigns in New York and New Jersey in 1776 and 1777, the campaign to Philadelphia in 1777 and the retreat from that city in 1778. Shortly after the British advance up the Hudson River in June 1779, however, he deserted from Verplanck’s Point, New York.[4]

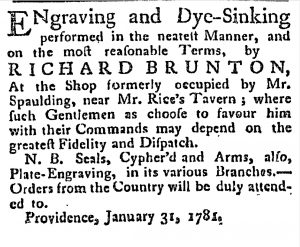

How he spent his time after he deserted until his marriage to Polly (aka Mary) Fullerton in Boston in October of 1779 is not known. Once in Boston, he advertised his services as an engraver and diesinker at a shop on Quaker Lane in the heart of the city.[5] Alas, the operation soon folded and he and his wife moved to Providence, Rhode Island. Despite advertising, and the presence of a French garrison bolstering the local economy (Fig. 1), once again he failed to make a living from his craft.

The next mention of him is in the town records of Groton, Massachusetts, of January 1783, when he and his wife “last of Providence” were warned out of town.[6] The couple then settled briefly in nearby Pepperell where the death of their infant son is recorded two months later. After that he and his wife seemed to have parted ways or she, too, passed.

![Richard Brunton, Angus Nickelson Family Register, circa 1790 (Charles McKew Parr Collection in the Archives of the Magnus Wahlstrom Library, University of Bridgeport, Bridgeport, Connecticut).[12]](https://allthingsliberty.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/An-Artist-Fig.-2-226x300.jpg)

Like Brunton, Earl was an itinerant who led a life on the fringe. After preparing his famous drawings of the Battle of Lexington to be engraved by Amos Doolittle in 1775, Earl declared his loyalty to the king and passed intelligence to the British. In 1777, he escaped to England disguised as a servant to a British officer. The rest of the war years in England he spent perfecting his craft of portrait painting. In 1785, he returned to America, where long-standing money problems caught up with him. In 1786, he was imprisoned in a New York City jail, where he painted portraits until 1788, when he was finally able to pay his debts and secure his freedom. By the time the two men were working in New Milford, Earl’s career was again on the rise.[7]

In contrast, Brunton’s opportunities for making an honest living from his craft were dwindling. Owing to an influx of printed matter from Europe, along with the arrival of more skilled engravers offering a greater variety of engraving techniques, Brunton’s somewhat archaic style of line engraving rapidly lost its appeal. Moreover, his life as an itinerant craftsman, traveling on country roads by horseback or stage, may well have been taking its toll. Not only was he lame, as reports indicate, he was getting older.

![Attributed to Richard Brunton, A Perspective View of Old Newgate, Connecticut’s State Prison, Granby, Connecticut, circa 1799 (Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford).[13]](https://allthingsliberty.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/An-Artist-Fig.3-295x300.jpg)

After his release, he returned to Massachusetts and once again was operating on the wrong side of the law. In 1807, he was captured in Boston with the tools of his trade and samples of counterfeit bills he had made. For this, he was given a life sentence to Massachusetts state prison in Charlestown.[10] While there he occupied himself again with legitimate work, engraving family registers, silver tokens and plates for advertisements such as his stagecoach broadside – one of the earliest graphic images depicting transportation in the New Republic.

In 1811, Brunton petitioned the Massachusetts governor for his freedom claiming he was lame and not long for this world, and that he would return to his native country.[11] Instead he returned to his old stomping ground of Groton, Massachusetts where he would spend the rest of years until his death in the poorhouse there in 1832.

As Don N. Hagist has observed, “the story of this British engraver-turned-soldier who then became an itinerant American engraver, artist and criminal is a startling example of a deleterious life that left a beautiful legacy.”[14]

[1] Commitment registers, Massachusetts State Prison, 1805–1824, HS9.01/.Series 289X, at Massachusetts State Archives, Dorchester, Mass. December 7, 1807 entry cites his age as 58, his place of birth as Birmingham, Warwickshire, England.

[2] Richard Brunton, apprentice engraver, Birmingham, Warwickshire, England, 1766, Apprenticed to Joseph Troughton, £30/00/00. Board of Stamps Apprenticeship Books at National Archives of the UK, Series IR 1: 56, folio 65.

[3] Muster rolls, 38th Regiment of Foot, WO/5171/2, British National Archives. Thanks to Michael Gandy of the Association of Genealogists and Researchers in Archives, agra.org.uk, for locating Brunton in these muster rolls.

[4] Muster rolls, 38th Regiment of Foot, WO/5172, British National Archives; Brunton’s desertion is recorded as occurring on June 6, 1779.

[5] “Engraving, Jewellary [sic], and Silver-smith’s Work performed in the neatest Manner, by Brunton, Gordon and Quirk, from Europe” New England Chronicle (Boston), March 20 – May 4, 1780.

[6] Groton Town Records and Meetings with Births, Marriages, and Deaths. Ancestry.com, image 24/293.

[7] For an in-depth study of this artist’s work and career, see Elizabeth Mankin Kornhauser, Ralph Earl: The Face of the Young Republic (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1991).

[8] State of Connecticut v. Richard Brunton, trial record dated December 12, 1795, record group 3, Judicial Dept., Hartford County Superior Court, Drawer 23, Connecticut State Library, State Archives, Hartford.

[9] State of Connecticut v. Richard Brunton, trial record dated March 25, 1799, record group 3, Judicial Dept., Windham County Superior Court. Drawer 190, Connecticut State Library, State Archives. Hartford

[10] Suffolk, Supreme Judicial Court, Indictment v. Richard Brunton counterfeiting, Nov. term 1807, Judicial Archives, Mass. Archives, Boston. File accessed courtesy of Elizabeth Bouvier.

[11] Council pardon files, 1811, Richard Brunton, Massachusetts State Archives, GC3/series 328. Reference courtesy archivist Jennifer Fauxsmith.

[12] Richard Brunton, Angus Nickelson Family Register, circa 1790 (brass, 14 ½ x 11 ¼ inches). Charles McKew Parr Collection in the Archives of the Magnus Wahlstrom Library, University of Bridgeport, Bridgeport, Connecticut. This plate is the largest and most ambitious of his family registers known. It is also the only example found where he inscribed his name “R. Brunton, sculp.” and the only one known that is not reversed for printing. As such, it must have been designed to be displayed as a plaque on a wall or table.

[13] Attributed to Richard Brunton, A Perspective View of Old Newgate, Connecticut’s State Prison, Granby, Connecticut, circa 1799 (line engraving, 20 ½ x 20 ¼ inches). Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford. This is Brunton’s most elaborate and largest engraving extant. Primitive as the perspective may be, it clearly shows the wooden palisade fence with spikes which surrounded the prison prior to the erection of a steep stone wall and gate in 1802. Only two other original impressions are known. In 1870, another six to eight impressions were taken before the actual plate was moved to Boston and cut up.

[14] The author would like to acknowledge Don N. Hagist for his generous sharing of source material and scholarship which gave me a much-needed context for understanding Brunton’s military career.

The above article is based on my book Soldier, Engraver, Forger-Richard Brunton’s Life on the Fringe in America’s New Republic, published by New England Historic Genealogical Society, Boston, Massachusetts.

One thought on “Richard Brunton: An Artist of No Ordinary Character”

Deborah,

Nicely done! Since we last communicated, I am still unable to find any connection between Brunton and his notorious contemporary, New Hampshire native counterfeiter Stephen Burroughs (1765-1840).

However, I have no doubt that he was not known in some fashion as Burroughs and his gang spread incredible discord here in Vermont, as well as in New York and Quebec. While Brunton worked to the south as you describe, this other group’s counterfeiting activity was so devastating to Vermont’s nascent banking industry (circa 1806) that it practically undermined the financial underpinnings of the state.

In fact, the counterfeiting was so prevalent here that it resulted in the legislature creating the state prison in Windsor in 1808 (opening the next year); and the first six prisoners admitted to that institution were counterfeiters, only to be followed by three murderers in the following days. That shows you the priorities of the day!

Regardless, both Brunton and Burroughs were wonderful artists!