In the aftermath of General Burgoyne’s defeat at Saratoga, many Loyalists in the New York and Hampshire Grant regions chose to flee to the safety of Canada rather than face the prospects of poor treatment, forfeiture of property and imprisonment at the hands of local rebels. When loyalists left their communities and traveled north to Canada, they usually followed one of two routes. Loyalists from New York typically followed an overland route through Native American territory to Lake Ontario. Because much of the travel was along forest trails, Indian guides were essential.[1] Unfortunately for many refugees, the route included passage through territory held by the Oneidas, allies of the Americans. Likewise, refugees had to avoid Continental and militia detachments that actively patrolled the region. Once clear of enemy territory, refugees crossed Lake Ontario at Oswego or followed the southern shore of the lake to the Niagara River.[2] The trip along the Niagara was often difficult, especially in time of spring floods.

Those refugees from the Hampshire Grants usually followed a combined land and water route along Lake Champlain and the Richelieu River to Montreal.[3] The roads followed were often muddy and in poor condition. Refugees could only use pack horses, ponies, or hand and horse carts for their belongings and provisions. Securing water transportation was critical to the flight north.[4] While travelling on water, refugees were often forced to seek shelter on insect infested or low lying islands in the middle of Lake Champlain. Because of the difficulties of this combined land-water passage, loyalists were forced to travel in groups whose members could share the burden of carrying boats and provisions.

Some loyalists might be lucky enough to make the trip in thirteen days, but most took much longer. An expedition of women and children that had to move slowly, was not lucky enough to make good connections with boats, and experienced bad weather could take from two to three months to reach the Quebec Province.[5] The delay in travel combined with the rugged country took its toll on the clothing of loyalist women and children.[6] Likewise, it was not uncommon for refugees to exhaust their supplies and be forced to survive on nuts, roots and leaves.[7]

The experience of loyalist Mary Munro highlights the hardships loyalist women encountered during the Revolutionary War. Mary Munro had been forced to flee from her home in Shaftsbury to Canada following the defeat of Burgoyne. As they traveled towards Lake George to join others en route to Canada, they lightened their load by discarding food and “most of their wearing Apparel. . . After much difficulty, [they] arrived at Lake George and . . .lay in the woods Six days almost perished with Cold and Hunger . . . until three other families arrived… [afterwards they] prevailed on the commanding officer at Fort Edward to give them a boat and a flag, they set off across Lake George.”[8] Unfortunately for Mary, they were “discovered by a party of Indians from Canada – which pursued them. . . as a result of the excessive hardships they underwent,” Mary and her children were “very sickly the whole Winter” after arriving in Canada. The toll the journey took on Mary was sadly announced by her husband when he declared “the children recovered but Mrs. Munro never will.”[9]

The British government controlling Canada was ill prepared for the arrival of thousands of men, women and children who Governor Frederick Haldimand fittingly described as “loyalists in great distress.”[10] As a result, the Crown adopted a policy similar to governmental treatment of the poor in England. Incoming loyalists were questioned to determine what trade or profession they possessed and then were dispatched to specific locations to seek employment. Destitute loyalists, including the sick, infirm, children, women with infants, and cripples, were assigned to refugee camps and placed on public assistance. However, “public assistance” in the 18th century differed greatly from modern practices. Under 18th century British policies, those on public assistance received only bare necessities at minimal costs. More importantly, those on assistance were expected to work in exchange for aid. At many refugee camps, women and children were expected to make “blanket coats, leggings at cheaper rates than the Canadians.”[11] To keep expenses low, loyalist women and children were mustered once a month so they could be inspected to determine whether or not they still qualified for public assistance.[12]

Unfortunately, the efforts of the British government to provide asylum for the loyalists were often in vain and as the years progressed, existing difficulties were compounded with an ever greater influx of refugees. Housing was the greatest problem. On September 14, 1778, Haldimand’s secretary, Conrad Gugy, complained about the lack of pine wood to construct necessary housing for the refugees.[13] By December and the onset of the Canadian winter, loyalist housing was not complete.[14] On January 7, 1779, Haldimand demanded to know why officials assigned to Machiche had not yet built a saw mill necessary for the construction of housing and military barracks.[15] British authorities even experienced difficulties establishing a schoolhouse for refugee children.[16]

Living quarters for loyalist refugees were cramped at best. In December 1778 one hundred and ninety six refugees at Machiche were distributed among twelve buildings. The following year, over four hundred refugees were placed in a mere twenty-one buildings. Records suggest that these structures were only eighteen by forty feet in size.[17]

Throughout the fall months of 1778, British officials likewise struggled to supply the loyalists with rations, candles and blankets.[18] By 1783, over three thousand loyalists were in need of basic clothing, including over three thousand pairs of stockings and shoes and sixteen thousand yards of linen and wool.[19] The following year, British officials warned that several refugees had died “owing as they think for the want of provisions and clothing.”[20]

Food supplies and cooking equipment were exceedingly difficult to procure as more loyalists arrived in Canada. Fresh meat was continuously scarce[21] and full rations often withheld.[22] Conrad Gugy complained to Haldimand that the children at Machiche were severely malnourished and many mothers were depriving themselves of their own food in an effort to keep their children alive.[23] To complicate matters, in 1778, the refugees at Machiche were only issued twenty-four kettles and eight frying pans.[24] To alleviate this problem, loyalists were encouraged to grow or secure their own food. To assist in this venture, Mr. Gugy established a pasture for fifty cows and a garden for growing vegetables at Machiche.[25] Unfortunately, the efforts to establish self-sufficiency among the loyalists failed miserably. By 1780, over two hundred and sixty-two men, three hundred and eight women and seven hundred and ninety eight children at various refugee camps outside of Montreal alone were receiving public assistance in the form of food supplies from the government.[26]

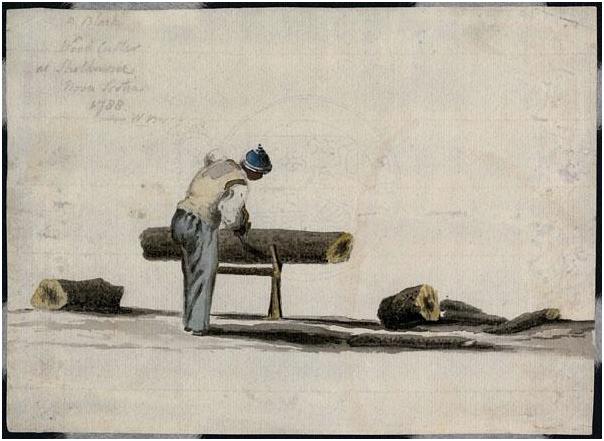

The treatment of African-American loyalists during the American Revolution, including those in Canada, was especially problematic. British authorities encouraged slaves to profess their loyalty to the Crown in exchange for freedom. However, once escaped slaves reached British lines, African-Americans found that the promises were not always fulfilled. Some were taken prisoner and either claimed as property by their captors or sold for profit. Likewise, British officials consistently maintained that former slaves of loyalists had to be returned to their masters. Only a few were allowed to serve as soldiers. Many loyalist officers protested the treatment of African-American loyalists. One officer, Daniel Claus, asserted that African-American soldiers were often of great help to scouting and raiding parties. He then noted sadly that sixteen blacks he had brought in as recruits “for their loyalty … now are rendered Slaves in Montreal.”[27]

From the refugee perspective, most were horrified at their living conditions and lack of provisions. As one group of loyalists opined, “we shall not be able to overcome the Seveir and approaching hard winter … [in] a Strange and Disolate place where [we] can get nothing to Work to earne a Penney for the Support of Each Other . . . much more the Bigger part of us Without one shilling in our pockets and not a Shew on our feet.”[28] Another loyalist complained that his refugee camp was a “drowned bog without water.”[29] Many refugees accused Gershom French, a loyalist in charge of supplies at Machiche, of abusing loyalists and diverting basic materials to himself.[30]

To contain the impact of refugees on the Quebec Province, British authorities restricted loyalists and refused to let them travel outside of their respective camps. As a result, refugees quickly discovered that they could not supplement their meager supplies with trips to neighboring towns and villages. Services, including laundry, were subject to price fixing under the threat of being removed from public assistance.[31] Likewise, requests to sell goods, including alcohol, to complement their meager living conditions were summarily denied.[32]

An even greater concern amongst refugees was the presence of camp fever which was quickly spreading through the refugee sites. Other deadly diseases present at the camps included malaria, small pox and pneumonia.[33] Loyalists chaffed at the government’s downplay of the camp conditions and the assertion that their complaints were “frivolous”.[34] According to a letter from Gugy to Stephen DeLancy, inspector of the loyalist camps, he was “well aware of the uniform discontent of the Loyalists at Machiche . . . the discontent . . . is excited by a few ill-disposed persons. . . . the sickness they complain of has been common throughout the province, and should have lessened rather than increased the consumption of provisions.”[35]

As years passed and loyalists continued to be confined inside refugee camps, families and individuals collapsed under the psychological burden. Long term absences of loyalist men on military missions only exacerbated the situation. There was one recorded incident of infanticide at Carleton Island where a mother killed her newborn.[36] Marriages crumbled, alcoholism rose, suicides increased and emotional breakdowns became commonplace.[37] In short, death and tragedy surrounded the loyalists in Canada.

From the British perspective, Haldimand became exasperated with the refugees in his colony and described them as “a number of useless Consumers of Provisions.”[38] He summarized the distaste British authorities had for the grievances from unappreciative loyalists when he told a prominent refugee “His Excellency is anxious to do everything in his power for the Loyalists, but if what he can do does not come up to the expectation of him and those he represents, His Excellency gives the fullest permission to them to seek redress in such manner as they shall think best.”[39] In short, Haldimand utilized loyalist dependency to maintain government control over the refugees. The loyalists were forced to choose between accepting their camp conditions or fend for themselves.

[1] Janice Potter MacKinnon, While the Women only Wept, (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1993), 89.

[2] Ibid, 87.

[3] Ibid, 88.

[4] Those loyalists who failed to secure boats often found themselves trapped in the Hampshire Grants.

[5] Ibid, 89.

[6] Henry Watson Powell to Governor Frederick Haldimand, July 10, 1779, Haldimand Papers, Add Mss 21,793, British Library (hereinafter HP). One traveler wrote, “the wet Weather, the Badness of the Roads, and the various Difficulties of so long a Journey, at this late season of the Year which seemed at once to encounter me, were sufficient to discourage one who had scarce ever been from Home before. But the Prospect before me of pursuing my original Plan of Life, and enjoying Peace with all its attendant Blessings made me look upon the Fatigues of the Way as Trifles. When travelling through the Wet and Dirt, I would say to myself by way of comfort this will make a fair Day and good Roads the more agreeable. And indeed we should not know the Value of good Things did we not sometimes experience their contrary Evils.” Richard Cartwright Jr. “A Journey to Canada, c. 1777,” http://www.62ndregiment.org/A_Journey_to_Canada_by_Cartwright.pdf

[7] MacKinnon, While the Women only Wept¸89-90.

[8] Memorial of Captain John Munro, August 17, 1784, AO 13/56, National Archives of Great Britain. MacKinnon, While the Women only Wept, 92.

[9] Memorial of Captain John Munro, AO 13/56.

[10] Haldimand to Lord George Germain, October 14, 1778, HP 21,718. Estimates place the number of non-military loyalists in Canada following the defeat of Burgoyne at over one thousand men, women and children. By 1780, the number of loyalist refugees in Canada had grown to five thousand. By 1784, the number would increase to seven thousand.

[11] Regulations as to the Lodgings and Allowances for Loyalists, March 6, 1782, HP 21,825.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Conrad Gugy to Haldimand, September 14, 1778, HP 21,824. Construction of the first set of barracks was not completed until November 8, 1778. Gugy to Haldimand, November 8, 1778, HP 21,824.

[14] Gugy to Haldimand, December 20, 1778, HP 21,824.

[15] Haldimand to Gugy, January 7, 1779, HP 21,824.

[16] Gugy to Haldimand, March 6, 1779, HP 21,824; Gugy to Haldimand, March 14, 1779, HP 21,824.

[17] List of Loyalists and Their Families lodged at Machicheat This Date, December 2, 1778, HP 21,825; Gugy to Haldimand, November 16, 1778, HP 21,824.

[18] Gugy to Haldimand, October 30, 1778, HP 21,824; Gugy to Haldimand, November 8, 1778, HP 21,824; Gugy to Haldimand, November 16, 1778, HP 21,824.

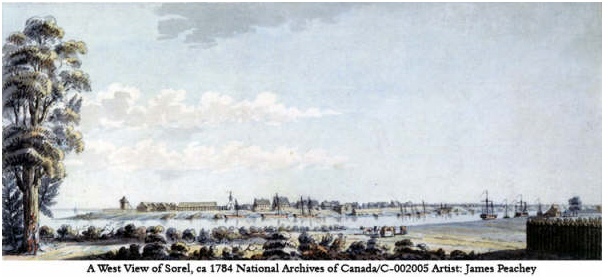

[19] Estimate of Clothing Required to Clothe the Above Numbered of Refugees, Agreeable to the Proportions Heretofore Granted, 1783, HP 21826. That same year loyalists at Sorel were supplied with “360 yards of linen cloth, 149 yards of wollen cloth, 73 blankets, 110 pairs of stockings, 106 pairs of shoes and 10 pairs of short leggings and mitts.” Haldimand to (?), December, 1783, HP 21,826.r 600 loyalists in and around Sorel at the time of this issuance ion by 1785. es. These loya It should be noted there were over 600 loyalists in and around Sorel at the time of this issuance.

[20] Stephen Delancey to Robert Matthews, April 26 and May 4, 1784, HP 21,825.

[21] Gugy made no less than two requests in November, 1778 for provisions of fresh beef for the loyalists at Machiche. Gugy to Haldimand November 8, 1778 and November 16, 1778, HP 21,824.

[22] Matthews to Abraham Cuyler, November 18, 1782, HP 21,824.

[23] Major John Ross to Sir John Johnson, September 11, 1780, HP 21,824. Daniel McAlpin would also complain about the state of loyalist children and families under his care. “All are in a state of distress . . . and are in urgent need of help.” Daniel McAlpin to Haldimand, July 1, 1779, HP 21,819.

[24] Gugy to Haldimand, November 16, 1778, HP 21,824.

[25] Haldimand to Germain, October 15, 1778, HP 21,819.

[26] MacKinnon, While the Women only Wept, 107-110.

[27] Daniel Claus to Haldimand, December 9, 1779, HP 21,774, MacKinnon, While the Women only Wept, 102.

[28] Petition by His Majesty’s Faithful Subjects Emigrated Under the Conduct of Captain Michael Grass from New York to This Place, Sorel, September 29, 1783, HP 21,825.

[29] Gugy to Haldimand, October 2, 1778, HP 21,819; Petition to Mr. Gugy, November 12, 1778, HP 21,819.

[30] Complaint by John Peters, January 20, 1780, HP 21,827.

[31] “The loyalist women receiving rations are to wash for the non-commissioned officers and men of the volunteers at four coppers a shirt and in proportion for other things.” Haldimand to Lieutenant French, July 14, 1780. HP 21,821.

[32] Claus to Haldimand, November 19, 1778, HP 21,774.

[33] Ross to Haldimand, November 25, 1782, HP B125, 85. MacKinnon, While the Women only Wept, 118.

[34] Gugy to Haldimand, October 2, 1778, HP 21,824.

[35] Gugy to DeLancy, April 29, 1780, HP 21,723.

[36] Ibid.

[37] W. Stewart Wallace, The United Empire Loyalists: A Chronicle of the Great Migration, Volume 13. (EBook, 2004), http://www.gutenberg.org/files/11977/11977.txt. See also Tuttle to Matthews, July 11, 1781, HP 21,819; MacLean to Matthews, November 24, 1779, HP 21,789; St. Leger to Haldimand, November 16, 1782, HP 21,789; Claus to Haldimand, June 14, 1784, HP 21,774. There are period accounts of several “insane loyalists” being sent from refugee camps to hospitals in Quebec.

[38] Haldimand to Johnson 23 May 1780, HP 21,819; Haldimand to Powell, 15 March 1780, HP 21,734.

[39] http://www.canadiangenealogy.net/chronicles/loyalists_quebec.htm

9 Comments

Well done, Mr. Cain. I see on Amazon J. M. Le Moine recently wrote a biography of Frederick Haldimand in French, I wonder if there is a good and available bio in English.

Oops. It appears the Le Moyne biography is 22 pages long, and a reprint. So the qyuestion still remains: are there any good biographies of Haldimand?

Hi Will,

Thanks for the kind words! Unfortunately outside an unpublished doctoral thesis from John Dendy and an early 20th century work by Jean McIlwraith, there really isn’t much out there for biographies on Haldimand. Surprising since he left so many writings behind!

Sorry!

Alex Cain

An excellent article!

In addition to the loyalists experiences you cite, there were some Vermont loyalists who were really “loyal to potential of a Vermont” separate from New York and the other colonies. They joined the British cause as the best way to obtain formal recognition of Vermont.

For a description of how these loyalists were treated by Haldimand and the British authorities, see Jennifer and Wilson Brown’s book “Colonel William Marsh – Vermont Patriot & Loyalist”. Marsh and his sons helped gather intelligence after Burgoyne’s defeat on the political and military situation in Vermont and participated in activities to peacefully return Vermont back to the Crown.

In recognition for their war time service, Marsh, his family and other Vermont loyalists were awarded Canadian land grants. However, Marsh and one son returned to live in Vermont. In the reverse, many “Vermonters” emigrated to Canada to live with their neighbors who obtained land grants for their military service.

I just came across this article, and I’m fascinated by it. Mr. Cain paints a wonderful canvas in my mind of the events following the Revolution. My ancestors were some of the Loyalists who fled to Canada, and I’ve never come across any information of what they endured. Thank you for writing this. I’m saving a copy for my personal records.

Heather,

Thank you very much! The plight of the Loyalist refugees in Canada was absolutely heartbreaking. What struck me the most during my research was the number of children who occupied refugee camps and the lack of some supplies available to them. If you need any additional material please don’t hesitate to contact me!

Alex

Mr. Cain,

Is there a list of names of wives and children that were sent to Machiche in 1783?

Thank you for any help you can provide.

Thanks so much for writing this! My father’s side of the family from Michigan, found out some time ago that they are descendants of royalist refugees. I’ll be glad to add this to the family archives. 🙂

This article painted a brilliant picture of what life was like for some of my ancestors. Growing up in eastern Ontario I live around many historical sites of famous battles. It never occurred to me that there were refugee camps until my mother mentioned my 6th great-grandparents dying of starvation in Machiche. I came here looking for more information to broaden my understanding. Really glad I came across this in the search engine.