According to some local sources, “Long island was the Thermopylae of the Revolution and the Pennsylvania Germans were its Spartans.”[1] While laden with hyperbole and bias, this is the claim made about the Northampton County Flying Camp battalion under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Peter Kichline.[2] Kichline’s battalion, made up of four companies—two of which were severely understrength—had become attached to Lord Stirling’s forces just prior to the opening of the Battle of Long Island.[3] These four companies played an integral part in the engagement and yet are often barely mentioned in histories of the battle (far too often no mention is found about them at all).[4] This article hopes to remedy that.

What can’t be fixed—at least not apparently—is the limited information that exists about the Flying Camp as a whole. Due to the passage of time and poor record keeping, less than 12% of the names of the 4500 officers and men of the Pennsylvania Flying Camp are known.[5] Beyond those who participated at Long Island, even less survives. Normally this would be an annoyance, but locating the extant documents has been part of the fun of writing this paper.[6]

“What was the Flying Camp?” you might be asking. While this question deserves its own full treatment, I’ll give you the abbreviated version as it relates to Northampton County, Pennsylvania (partly due to space limitations and partly to give the editors a break from my normal, lengthy articles). At the onset of the summer of 1776, General Washington needed more troops. Congress, therefore, acted to supplement the army with volunteers. On 3 June 1776, Congress resolved:

“That a flying camp be immediately established in the middle colonies; and that it consist of 10000 men; to complete which number, Resolved, That the colony of Pennsylvania be requested to furnish of their militia… 6,000.[7]

Congress then resolved a day later that these men all be outfitted appropriately by the respective committees, “to take particular care that the militia come provided with arms, accoutrements and camp kettles.”[8]

At this point, Pennsylvania did not have a militia law on the books; instead, they had volunteers, known as Associators, usually supplied by their commanding officers; about 1500 Associators were under the pay of the province at the time of the request for the Flying Camp.[9] Therefore, the Provincial Assembly resolved, in conjunction with these men already fielded, “That this conference do recommend to the committees and associators of this province to embody 4,500 of the militia, which with the 1,500 men now in the pay of this province, will be the quota of this colony required by congress.”[10]

Local committees at the county level were simply too busy dealing with dissent from Tories and the disaffected within their communities to attempt recruitment, especially in Northampton County.[11] The authorities in Pennsylvania would not press the issue of raising troops for almost a month after Congress resolved to raise them.

While the Flying Camp was recruited from volunteer militia companies, the Flying Camp itself was not considered a militia organization. Unlike the Associators, which served at the county level, the Flying Camp was called up by Congress and therefore under Continental pay and in Continental service, meaning that these were Continental troops (even though they weren’t considered Regulars).[12]

When the Provincial Assembly published the resolves of Congress in The Pennsylvania Packet on 1 July 1776; the following was included:

“Resolved unanimously, That the 4500 Militia recommended to be raised, be formed into six battalions; each battalion to be commanded by one Colonel, one Lieutenant Colonel, one Major; the staff to consist of a Chaplain, a Surgeon, an Adjutant, a Quarter-Master, and a Surgeon’s Mate; and to have one Serjeant Major, one Quarter-Master Serjeant, a Drum-Major, and a Fife-Major; and to be composed of nine companies, viz. Eight battalion companies, to consist of a Captain, two Lieutenants, and one Ensign, four Serjeants, four Corporals, a Drummer, a Fifer, and 66 Privates each; and one Rifle Company, to consist of a Captain, three Lieutenants, four Serjeants, four Corporals, one Drummer, one Fifer, and 80 Privates.”

These were extremely idealized numbers. Only a handful of battalions outside of Philadelphia were able to meet or come close to these figures. It seems that the Chairman of the Assembly, Thomas McKean, was well aware of the unrealistic expectations and so he included a provisional resolution and published it just below the latter one in the same paper:

“That it be recommended to the Committees of Inspection and Observation…for each County to order the Militia aforesaid to be raised out of the Battalions associated within their respective limits, in such proportions as they shall judge most equal.”

On 3 July 1776, Congress passed a further resolution to rush recruitment:[13]

“Resolved, That a circular letter be written to the committees of inspection of the several counties in Pennsylvania, where troops are raised, or raising, to form the flying camp, requesting them to send the troops by battalions, or detachments of battalions, or companies, as fast as raised, to the city of Philadelphia, except those raised in the counties of Bucks, Berks, and Northampton, which are to be directed to repair, as aforesaid, to New Brunswick, in New Jersey.”

That same day, John Hancock would write to Washington of these resolves and ask him to choose a commanding officer to lead the Flying camp.[14]

Throughout midsummer, fears of an attack on New York prompted some panic; word spread to the communities in Northampton that refugees from the colony of New York were fleeing into Pennsylvania in order to escape what many viewed as the inevitable.[15] But Washington also feared that the British would target New Jersey while New York was fortified and reinforced. On 10 July, Thomas McKean published the following additional resolves to the Pennsylvania Associators:[16]

“Resolved, That it appears to the Conferees, that all the Associated Militia of Pennsylvania, excepting the Counties of Westmoreland, Bedford and Northumberland, who can be furnished with arms and accoutrements, should be forthwith requested to march with the utmost expedition to Trenton, (except the Militia for Northampton County, who are to march directly for New-Brunswick) in New-Jersey; and that the said militia continue in service until the flying camp of ten thousand men can be collected to relieve them, unless they shall be sooner discharged by Congress…. That the militia march by companies to the place of rendezvous.”

Despite the complexities of these concurrent resolves, there was a method to the madness. Congress was well aware that many Pennsylvania counties would be slow to comply given the circumstances within the state. Sending militia seemed to be the most expedient way to provide for a temporary defense of New Jersey while waiting for the Flying Camp to materialize. But sometimes strategies that look great on paper are terrible in their execution.

Understandably, the local county committees were perplexed with how to synchronously raise their Flying Camp battalions from the Associators while sending those same Associators (which were needed to, you know, fill the Flying Camp) to New Jersey. It was very nearly a spectacular disaster. It was so incredibly convoluted that Congress, as well as the command staff, had trouble deciding which unit was part of the flying camp and which units were Associators. To make matters more complicated, Congress then raised the quota from Pennsylvania by four additional flying camp battalions.[17] The requested augmentation taxed the ability of local committees to recruit their companies of men.

Northampton County was no exception. Although some battalions of the Flying Camp and Associators made it into New Jersey shortly after the resolutions were issued to the committees,[18] Northampton was slow to proceed. The minutes of the Committee of Observation in Northampton show that on 9 July, the county had only just begun discussing their quota and approved an added enlistment bounty of £3 per recruit for the flying camp.[19] That same session, they were also dealing with charges of corruption from the local disaffected. Colonel Kichline himself was accused by another member of the committee of taking a bribe or reward to use his influence to keep up support for the local patriot government in the County.[20]

As stated elsewhere, the county suffered from a shortage of firearms. A Moravian diarist notes that on 23 July, Colonel Kichline had come through Bethlehem and collected nearly all the guns in the village to supply the county troops; he left a few there for the Moravians to defend themselves should they have a need. While a magnanimous gesture, it was for naught; a few days later a former member of the local committee, George Taylor (at that time an elected member of Congress), gathered up the rest.[21]

Finally, by 30 July, the flying camp was on the move. According to the diarist, “One hundred and twenty recruits from Allentown and vicinity, passed through on their way to the Flying Camp in the Jerseys, to which our County has been called on to contribute 346 men.”[22] But the numbers never reached that requested total, despite the number of Associators.[23]

Out of Northampton’s four companies, only one was at full strength (Captain Henry Hagenbuch’s company from the vicinities of Allen and Lehigh Townships at 108 privates) with one other company at nearly full strength (Captain John Arndt’s company—designated as the rifle company—of the area around Easton and Forks Township, made up of 87 privates), and two companies at less than half strength (Captain Nicholas Kern, consisting of 44 privates from Towamensing and Moore Township, and Captain Timothy Jaynes of Lower Smithfield Township, Plainfield Township, and the Delaware Water Gap, with 33 privates).[24] All in all, the Northampton County battalion commanded by Kichline consisted of 268 privates and 55 officers, NCOs and additional staff, falling well short of the quota. Two casks of gun powder and “what Lead can be got” were distributed amongst them.[25]

Not all the companies marched out at once either. While Captain Hagenbuch’s company had sent off for New Brunswick at the end of July, Captain Arndt’s company apparently began their march towards New Brunswick shortly before 5 August, and apparently at least one company had not yet departed by this date.[26] According to recollections of soldiers, however, all of the Northampton County companies were at Amboy—to whence they marched after New Brunswick to form with the other half of the Battalion of Bucks—by the second week of August.[27] From Amboy, according to the same accounts, they were marched to Fort Lee and were appearing on General Mercer’s returns by 20 August and had crossed to Long Island by 26August attached to the command under Lord Stirling.[28]

At around 1AM on the 27th, the fighting began along the Narrows Road just south-west from Lord Stirling’s position.[29] According to Colonel Samuel Atlee’s (of the Pennsylvania Musketry Battalion) deposition of the events that morning:[30]

“This morning, before day, the camp was alarmed by an attack made upon that part of our picket guard upon the lower road leading to the Narrows, commanded by Major Burd, of the Pennsylvania Flying-Camp. About daylight a part of General Lord Stirling’ s Brigade then in camp, viz: the Battalion of Maryland, Colonel Smallwood; the Delaware, Colonel Haslett; about one hundred and twenty of my battalion, Pennsylvania Musketry; and part of Lutz and Kiechlein’s [Kichline’s] Battalions, Pennsylvania Militia; containing in the whole about two thousand three hundred men, under the command of Major-General Sullivan, and the Brigadiers Stirling and Parsons, were ordered to march out and support the picket attacked by the enemy.”

Stirling’s account also indicates that around 3AM, he began to organize and form his men to meet Grant’s advance; he coordinated with Colonel Atlee and “desired Colonel Atlee to place his Regiment on the left of the Road and to wait their Comeing up, while I went to form the two Regiments I had brought with me, along a Ridge from the Road up to a peice of wood on the Top of the Hill, this was done Instantly on very Advantageous ground.”[31] After exchanging a few volleys, Atlee pulled back to the top of the hill and reformed his line. Stirling goes on to write that after Atlee had found his new position on Battle Hill:

“Kichline’s Rifle Men arrived, part of them I placed along a hedge under the front of the Hill, and the rest in the front of the wood. The troops opposed to me were two Brigades of four Regiments Each under the Command of General Grant; who advanced their light Troops to within 150 yards of our Right front, and took possession of an Orchard there & some hedges which extended towards our left; this brought on an Exchange of fire between those troops and Our Rifle Men which Continued for about two hours and the[n] Ceased by those light troops retireing to their Main Body.”

This part is interesting. That Kichline’s men, green as can be, engaged with hundreds of British light infantry only 150 years away, is fairly impressive. According to letters written about the battle a few days later:[32]

“The enemy then advanced towards us, upon which Lord Sterling, who commanded, immediately drew us up in a line, and offered them battle in the true English taste. The British army then advanced within about three hundred yards of us, and began a very heavy fire from their cannon and mortars, for both the balls and shells flew very fast, now and then taking off a head. Our men stood it amazingly well; not even one of them showed a disposition to shrink.”

Yeah, shells from canon were decapitating soldiers. Once you imagine it, you can’t unimagine it; yet as horrific as that might be to think about, it must have been a thousand times more terrifying to live it. After two hours of fighting in these conditions, however, Kichline’s battalion was sent to assist Colonel Atlee’s men for a short time. Atlee writes that after repulsing a few more attacks from Grant:[33]

“I now sent my Adjutant, Mr. Mentgis, to his Lordship, with an account of the successive advantages I had gained, and to request a reinforcement, and such further orders as his Lordship should judge necessary. Two companies of Riflemen, from Keichlien’ s Flying-Camp, soon after joined me, but were very soon ordered to rejoin their regiment, the reason for which I could not imagine, as I stood in such need of them.”

Atlee didn’t know, nor could he at the time, that his Musketry Battalion was in danger of being completely overrun.

Lord Stirling and his command were under the false belief that they were holding back the full force of the British Army, unaware that they were about to be flanked by some 5,000 Hessians under General von Heister pushing back General Sullivan at the center of the army. Meanwhile, Colonel Miles was engaging a far superior force on the far left of the army; this force, commanded by Cornwallis, Howe, Percy, and Clinton—a combined total of 10,000 men— descended upon Miles’ 400-strong regiment. Atlee confirms this:

“I fully expected, as did most of my officers, that the strength of the British Army was advancing in this quarter to our lines. But how greatly were we deceived when intelligence was received by some scattering soldiers that the right wing and centre of the Army, amongst whom were the Hessians, were advancing to surround us. This we were soon convinced of by an exceeding heavy fire in our rear.”

Atlee discovered after the battle why Kichline’s men had been sent back to their regiment:

“No troops having been posted to oppose the march of this grand body of the enemy’s Army but Colonel Miles’s two battalions of Rifles, Colonel Willis’s battalion of Connecticut, and a part of Lutz and Keichlien’s battalions of the Pennsylvania Flying-Camp.”

It seems that at some point after Kichline’s men had returned to their command, they were redeployed in the rear to discourage this large force, that was clearly on its way to destroy Stirling’s command, from pressing on as best as they could. Atlee waited about 45 minutes for orders from Stirling; no troops pressed his front and, at about 11AM, Atlee determined that withdrawing to where the rest of the command was located would be most prudent. When he arrived with his men at the location where Stirling had once been:

“How great was my surprise I leave any one to judge, when, upon coming to the ground occupied by our troops, to find it evacuated and the troops gone off, without my receiving the least intelligence of the movement, or order what to do, although I had so shortly before sent my Adjutant to the General for that purpose. The General must have known, that by my continuing in my post at the hill, I must, with all my party, inevitably fall a sacrifice to the enemy. An opportunity yet afforded, with risking the lives of some of us, of getting off.”

The large force attacking from the left and the Hessians moving up the center had forced Stirling’s and Sullivan’s forces to retreat. Kichline’s battalion had scattered by this point. Various personal accounts indicate that Kichline and Lutz had both been captured, along with most of their command staff, and their men—leaderless and having already suffered heavy casualties fighting in the rear of Stirling’s and Atlee’s positions—withdrew in a panic with the rest.[34]

The aftermath for the whole army deployed that day is pretty terrible and Kichline’s battalion suffered just as poorly. Given the half-strength size of his battalion entering the battle, the amount of devastation it witnessed has been underreported. In his pension deposition years later, Henry Allhouse’s reported that “Colonel Kichline’s Battalion lost up-ward of 200 men & the Colonel & several other officers were taken prisoner—about 150 of our Battalion escaped, Captain Arndt and this declarant were among the number of those who escaped.” These numbers match what we learn from other depositions.

According to the one casualty list we have out of the four companies (the other three are missing or were just never taken), in Captain Arndt’s company 21 men were killed or captured at Long Island. Captain Arndt’s company largely managed to escape, but Captains Jayne and Hagenbuch were captured, along with Colonel Kichline.

On 4 September, Northampton County received some of the first news of the battle. According to the Moravian diarist, “Several deserters from the army passed through, and stated that in the battle of Long Island, one of the battalions from this county was badly cut up.”[35] An entry from another individual, from around the same date (between 2 and 6 September), relates similar whispers:[36]

“In these days, parties of militia on their return from New York, passed, bringing the intelligence that a battalion from the county has suffered severely at the engagement with the British, on Long Island, on the 27th of August last, having left most of its men either dead or wounded.”

The remnants of the Battalion were never again to have their own identity. Following the battle, General Washington ordered that:

“It is the Generals orders that the remainder of Lutz’s and Kachlein’s Battalions be joined to Hands Battalion; that Major Huys be also under the special command of Col. Hand; that then those Battalions, with Shee’s, Col. Magaw’s, Col. Huchinson’s, Col. Atlee’s, Col. Miles, Col. Wards Regiments be brigaded under General Mifflin, and those now here march, as soon as possible, to Kingsbridge.”[37]

To make matters worse for the Northampton County men, several of their officers who had survived capture or death were under suspicion of cowardice.

“A Court Martial, consisting of a Commandant of a brigade, two Colonels, two Lt Cols.—two Majors & six Captains to sit to morrow at Mrs Montagnie’s to try Major Post of Col. Kacklien’s Regt ‘For Cowardice, in running away from Long-Island when an Alarm was given of the approach of the enemy.[‘] The same Court Martial also to try John Spanzenberg Adjutant of the same regiment, for the same offence, and likewise Lieut. Peter Kacklein [Junior].”

To their credit, they were exonerated by their peers on the charge of cowardice:

“Major Popst of Col. Kackleins Battalion having been tried by a Court Martial whereof Col. Silliman was President on a charge of ‘Cowardice and shamefully abandoning his post on Long-Island the 28th of August’; is acquitted of Cowardice but convicted of Misbehaviour in the other instance—he is therefore sentenced to be dismissed [from] the Army as totally unqualified to hold a Military Commission.

“Adjutant Spangenburg and Lieut: Kacklein tried for the same Offence were acquitted. The General approves the sentence as to Spangenburg and Kacklein, and orders them to join their regiment: But as there is reason to believe farther Evidence can soon be obtained with respect to the Major—he is to continue under Arrest ’till they can attend.”

Major Pobst had to have been exonerated, as he later served as a Lieutenant Colonel of militia in Northampton County in 1777.

Captain Arndt, having returned following the engagement at Fort Washington, where he lost even more of his company (only 33 men rallied at Elizabethtown after the battle on 16 November, including Arndt),[38] faced accusations as well. Frederick Reager, who served under Arndt at Long Island and Fort Washington (who was himself wounded there), levied the accusation that Arndt hid behind a barn during the battle and had run away from his company at Fort Washington. Additional testimony from other members of Arndt’s command suggest he served admirably; according to Corporal Elijah Crawford, Arndt “by his good conduct saved about twenty of his Comp’y, who would have either been killed or taken prisoner.” The charges against Arndt were dropped by the Committee of Inspection and Reager was forced to sign a letter of apology for defaming him.[39]

The ripple effects of the Battle of Long Island on Northampton County are telling. While the second quota of the Flying Camp met with similar success (four companies of 278 men) in the fall and winter of 1776, the loss of so many active patriots was most assuredly a devastating blow to the committee at Easton and to the county as a whole. Northampton County soldiers saw additional service in 1776 and early 1777, but those who survived were constantly defending themselves against unbecoming charges of cowardice and desertion.

What is imperative to realize is that none of these accusations hold water. The depositions of the officers in command of the Battalion, Atlee and Stirling, are positive; the reports about the conduct of Kichline’s men—from their two-hour standoff with British Light Infantry, to the rear-guard defense of Atlee and Stirling from the flanking attacks in the late morning of the battle—are endearing, not dismissive or negative. In fact, Kichline and his Flying Camp battalion played a pivotal role in the fighting at different times during the day; the full effects of their actions may perhaps never be known (e.g., did they help prevent an all out attack on the hill?).

Their absence from accounts about the battle is bizarre, if not unsettling. For the American army, this was the first instance they would face the British on an open field of battle; they formed up in European style lines of battle and exchanged volleys with them, using an odd assortment of weapons—from muskets that were several decades old to modern rifles made in Northampton County by German gunsmiths—and they produced, during this engagement, one of the few successful actions of the day. The Northampton County Flying Camp battalion served quite admirably given their lack of experience and short time in the army. While suggesting they are akin to the Spartans at Thermopylae might be an overstatement, their deeds and sacrifice deserve a place in the light—as much as the Maryland and Delaware men also under Lord Stirling—rather than the obscurity they’ve been dealt.

/// Featured image at top: Lord Stirling at the Battle of Long Island, Virtue & Co. Publishers, 1859. Source: George Washington’s Mount Vernon

[1] F.C. Johnson, ed., The Historical Record: A Quarterly Publication Devoted Principally to the Early History of Wyoming Valley (Wilkes-Barre: Press of the Wilkes-Barre Record, 1897), 7:130.

[2] Along with the Northampton County Flying Camp battalion at Long Island was the Berks County battalion under Lieutenant Colonel Nicholas Lutz, a few companies from Lancaster County, and some from Chester County; this article primarily focuses on Northampton County’s contribution because of limited details of the role these other units played during the battle (also space requirements), though the sacrifices of all these men deserve to be remembered. It is my hope that another author or contributor will further outline the contributions of these additional Flying Camp forces at Long Island since it is clear they also saw heavy action.

[3] According to the Northampton County standing committee minutes, “Peter Kachline Esq. Lieut. Colonel of the first Battalion of Militia to be Lieut. Colonel of the said Flying Camp…to be composed partly from the County of Bucks and partly from this County;” Pennsylvania Archives (Harrisburg: The State Printer, 1907), Ser. 2, 14:609. Colonel Joseph Hart, from Bucks County, was given overall command of the Northampton and Bucks County battalions, however during the Battle of Long Island Colonel Hart was at Amboy with most of the companies from Bucks County. This is attested in pension files, like Michael Fackenthal’s of Bucks County, who was stationed with Colonel Hart; his file states: “In the year 1776 he enlisted, in Captain Valentine Opp’s company, in the said township of Springfield, was appointed Sergent of said company. It was one of the four companies from Bucks County that formed a regiment with four companies from Northampton County of the Flying Camp. Joseph Hart from said county of Bucks was appointed first Colonel, and Peter Kichline, from Northampton County, second Colonel. Colonel Kichline with four companies from Northampton county were in the engagement on Long Island, August 27, 1776, and was made prisoner with a number of his men. Colonel Hart was stationed at Amboy and the company I was with.” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 33 (Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1909), 255.

[4] For example, Barnet Schecter’s The Battle for New York: The City at the Heart of the American Revolution (Penguin Books, 2003) makes no mention of the Flying Camp under Stirling, despite the fact that every other unit deployed with Stirling gets a mention.

[5] As noted in the Pennsylvania Archives, Ser. 5, 7:17.

[6] This article was the result of several months’ work; it required examining actual manuscripts (which was just awesome, by the way), looking through a handful of pension files, scattered after-action reports and letters, in addition to the few notes found in the published Pennsylvania Archives. Special thanks to the research librarians at the Easton Public Library, Marx Room, for helping me find these manuscripts in the library archives. Also thanks to archivist Aaron McWilliams with the PHMC, Pennsylvania Archives for his diligence in locating additional, obscure Flying Camp manuscripts.

[7] Pennsylvania Archives, Ser. 2, Vol. 3:572.

[8] Pennsylvania Archives, Ser. 2, Vol. 3:572.

[9] See my article ‘Explaining Pennsylvania’s Militia’ for details about Pennsylvania’s complex militia system: https://allthingsliberty.com/2014/06/explaining-pennsylvanias-militia/

[10] Pennsylvania Archives, Ser. 2, Vol. 3:574.

[11] See primary source evidence of these local issues in my article ‘Disarming the Disaffected’: https://allthingsliberty.com/2014/08/disarming-the-disaffected/.

[12] This however didn’t sit entirely well with the Associator companies in Pennsylvania, many of whom knew this would deprive them of their numbers and would force them to march out of their own state; McKean had to address them directly. He noted that the council “presume only to recommend the plan we have formed [with the raising of men from the Associators] to you. Trusting that in case of so much consequence your love of virtue, and zeal for liberty will supply the want of authority delegated to use expressly for that purpose.” The Pennsylvania Packet,1 July 1776.

[13] Worthington Chauncey Ford, et al., eds. Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789 (Washington, D.C., 1904–37), 5:508.

[14] To George Washington from John Hancock, 4 July 1776, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-05-02-0136accessed 21 October 2014.

[15] As early as 13 June 1776, the diarist of the Moravians had recounted: “Intelligence came from Philadelphia that New York was expected to be attacked daily, and that the troops from the former city were moving thither.” John W. Jordan, Abraham Berlin, et al., ’Bethlehem During the Revolution: Extracts from the Diaries in the Moravian Archives at Bethlehem, Pennsylvania,’ The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 12, No. 4 (Jan., 1889), 389.

[16] These were published in The Pennsylvania Gazette, 10 July 1776.

[17] On 20 July, they resolved, “That the convention of Pennsylvania be requested to augment their quota for the flying camp, with four battalions of militia,…in addition to those formerly desires by Congress, and send the same, with all possible despatch, to the said flying camp.” Journals of the Continental Congress, 5:598.

[18] John Hancock wrote to the various committees, “I am directed by Congress most earnestly to request, you will supply the Flying Camp and Militia in the Jerseys, with as many Muskett Cartridges, with Balls therein, as you can possibly spare and send them forward with the greatest Dispatch. The State of our Affairs will not admit the least Delay, nor need I use Arguments to induce you to an immediate Compliance with this requisition.” The fact that he was already referring to militia and Flying Camp battalions located in New Jersey indicates pretty definitively that some gad already arrived. John Hancock to the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, 14 July 1776, http://web.archive.org/web/20110112181711/http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/etcbin/toccer-new2?id=DelVol04.xml&images=images/modeng&data=/texts/english/modeng/parsed&tag=public&part=369&division=div1accessed October 2014.

[19] Pennsylvania Archives Ser. 2, 14:607. On 17 July, the tax on Non-Associators and disaffected in the community was raised to “defray the expences of a Bounty of £3 to be given to those Men who are now raising to compose the Flying Camp…at 9d. pr. Pound, and that Single men pay at a rate of 6s. pr. Pound.” Pennsylvania Archives Ser. 2, 14:609.

[20] While these accusations were summarily ignored by the committee and the individual who raised them was brought before them and shamed into submission, the reader of the minutes (and of this article) is left to judge for themselves if such accusations hold any merit.

[21] Jordan, ‘Bethlehem During the Revolution’, 389.

[22] Jordan, ‘Bethlehem During the Revolution’, 390.

[23] Roughly 2,357 men from 26 townships had Associated; a fraction of the township, but far more than the few hundred men who joined the Flying Camp.

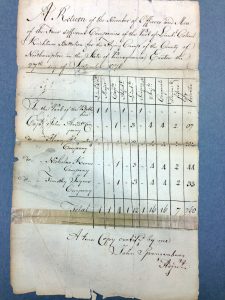

[24] These numbers are based upon a manuscript return, copied on 28 September 1776 on request from the Council of Safety, for means of paying the bounty money promised to the Flying Camp. The manuscript, made by the adjutant of Northampton County at the time, is located at the Easton Public Library. Jaynes’ company’s small size probably had a lot to do with the claims of Toryism in the region.

[25] Pennsylvania Archives,Ser. 2, 14:609.

[26] Pennsylvania Archives,Ser. 2, 14:612.

[27] Henry Allshouse, a fifer in Captain Arndt’s company, states the following course the Battalion took in his pension file (pages 1-2): “As soon as Captain Arndts company was organized it marched from Northampton County, Pennsylvania, where it was raised, first to Brunswick in New Jersey, from there to Amboy…in New Jersey, where it was joined by the rest of the Battalion—the whole Battalion then marched to New York, and encamped in sight of the North River about two miles above the city. We were ordered from there to Long Island, and encamped near East River.”

[28] As discussed in Francis E. Devine, ‘The Pennsylvania Flying Camp, July–November 1776’, Pennsylvania History, Vol. 46, No. 1 (January, 1979), 63-64. This is supported by Cornelius Brooks’ pension file, which notes: “That he enlisted in the year seventeen hundred and seventy six at the town of Lower Smithfield, County of Northampton, and state of Pennsylvania, as a fifer for six months into Captain Timothy Jaynes Company called the Flying Camp, that he marched immediately with the Company to Eastown [Easton], and joined the battalion, which was commanded by Colonel Kickline, that he then marched to Amboy in the state of New Jersey, and that while at Amboy the battalion to which he belonged at the request of General Washington, as he then was informed by his Captain, volunteered to go to New York. That he went with the Company and battalion to which he belonged to New York about the middle of August, that on the twenty-fifth or twenty-sixth of August he with the Company and battalion went over to Long Island…”

[29] Incidentally, it was the Pennsylvania Flying Camp, early in the morning at about 1AM on 27 August, which kicked off the fighting at Long Island. A detachment of riflemen from Colonel Lutz’s Berks County detachment, under Major Burd, on Long Island, deployed as pickets and advanced guards ahead of Stirling’s main body, encountered British troops under General Grant along the Narrows Road; being outnumbered 3-to-1, they worked to stall the advance of Grant’s men as long as they could while Stirling’s main force sought to organize itself along Gowanus Road and what became known as Battle Hill. Discussed at length in Devine, ‘The Pennsylvania Flying Camp’, 66; also mentioned in Atlee’s journal, above.

[30] Atlee’s account of the day’s events is found in Peter Force, American Archives (Washington, D.C., 1837–53), Ser. 5, V1:1251; but it is also available at http://lincoln.lib.niu.edu/cgi-bin/amarch/getdoc.pl?/var/lib/philologic/databases/amarch/.21526, accessed 21 October 2014.

[31] To George Washington from Lord Stirling, 29 August 1776, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-06-02-0135, accessed 21 October 2014.

[32] An unsigned letter dated 1 September 1776, http://lincoln.lib.niu.edu/cgi-bin/amarch/getdoc.pl?/var/lib/philologic/databases/amarch/.22414, accessed 21 October 2014.

[33] It was believed for a short time that Stirling’s men had actually killed General James Grant after an officer was slain and a hat was found with the name ‘Grant’ inside. It was later determined that the hat belonged to Lieutenant Colonel James Grant of the 40th Regiment; Atlee wrote in his journal: “The sentinels gave the alarm. Officers and men immediately flew to arms, and with remarkable coolness and resolution sustained and returned their fire for about fifteen minutes, when the enemy were obliged once more to a precipitate flight, leaving behind them killed Lieutenant-Colonel Grant, (a person, as I afterwards understood, much valued in the British Army,) besides a number of privates, and some wounded.” A letter dated 28 August, from the headquarters (unsigned) at Long Island, indicated, “This morning General Parsons came in with a few men; he brings an account that the enemy have lost five hundred men, and a hat, with two bullet holes, marked Colonel Grant, and his watch. I wish it was General Grant, but their great officers don’t like venturing.” American Archives, Ser. 5, 1:1195.

[34] American Archives, Ser. 5, 1:1195-1196; a letter (unsigned) from the battle indicates “Their retreat [Smallwood’s, Haslet’s, and Atlee’s battalions] was covered by the Second Battalion which had got into our lines. Colonel Lutz’s and the New-England regiments made some resistance in the woods, but were obliged by superior numbers to retire.” While it isn’t clear, Kichline’s men were most likely mixed in with Lutz’s men (given their proximity to one another behind the lines, given above in Atlee’s disposition).

[35] Jordan, ‘Bethlehem During the Revolution’, 391.

[36] The letter is reproduced in Henry Melchior Muhlenberg Richards, The Pennsylvania-German in the Revolutionary War, 1775-1783 (The Pennsylvania-German Society, 1908), 17:249.

[37] General Orders, 31 August 1776, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-06-02-0143, accessed 21 October 2014.

[38] It seems like Captain Arndt’s company of the original Northampton County battalion was the only one to be deployed to Fort Washington; according to pension files of men from other companies, they were stationed at Amboy or other locales in New Jersey until their enlistments expired—quite likely due to the heavy casualties these companies suffered.

[39] Pennsylvania Archives,Ser. 2, 14:620.

31 Comments

Archived casualty lists do not support the statement common in the histories of this battle that Samuel Miles had 400 men.

A head count of the two battalions of Miles’ Pennsylvania Rifle Regiment show 1077 present at The Battle of Long Island, with a total of 196 casualties as a result of the action on August 27, 1776; a total casualty rate of 18%. The heaviest casualties were in Rifleman Christopher Neuhart’s 1st Battalion, probably positioned as the far left screen of the American defense, with Captain Philip Albright’s company from York County losing 31 of 83; a 37% casualty rate. Other later lists show some not reported as casualties being prisoners, however, and those sick in hospital, detached, on authorized leave of absence or otherwise not available during the battle were counted in the archived rosters as present, so the actual casualty rate was undoubtedly higher, the loss of 50% of the regiment’s field-grade officers and 50% of the 1st Battalion’s company-grade officers contributing to the confusion. In turn, the regiment’s 2d Battalion incurred 62 casualties of 525 listed as present, a 12% casualty rate. They were probably adjacent to General Sullivan’s 1500-man division facing the Hessians, specifically, on the left of Wyllys’ 17th Continentals. Of note is that I have yet to find a historian who accounts for Miles’ 2d Battalion commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Daniel Brodhead of Berks County. All the major histories of this battle report Miles with only 4-500 men on the far left flank of the American lines, probably based on Washington’s instructions concerning the left flank during his visit on August 26th. But these 500 men were (probably) only Miles’ 1st Battalion under Lieutenant Colonel James Piper of Bedford County. The Pennsylvania Archives show Miles had over a thousand men present at the battle, with the unaccounted-for 2d Battalion clearly sustaining casualties on August 27th. Where that battalion was and who it reported to, however, remain questions (PA Archives Series 2 Vol X; Smith 27, 46-50).

Bob,

You’re quite right. The 1st Battalion, as you know, was Kichline’s battalion which is the subject of this article. And yes, they suffered high losses (and their position was actually squarely in the center of Stirling’s line for most of the morning, with the exception of a few detachments which were temporarily sent elsewhere in the engagement, only to return and support the rear).

If anyone is interested in checking out the manuscripts I was looking through, I took pictures and posted them up on my blog: http://historyandancestry.wordpress.com/2014/09/06/revolutionary-war-manuscripts-northampton-county-pennsylvania/

It is interesting that Col. Atlee claimed his men were facing British light infantry. Although every British regiment included a light infantry company composed of about 50 selected soldiers, in this and most other actions in America these companies (and their counterparts the Grenadier companies) were detached from their regiments and formed into composite battalions. In the battle on 27 August 1776, all of the British light infantry was in Gen. Howe’s flanking column on the British right; Gen. Grant had no light infantry in his two brigades.

Besides eight British regiments of about 400 professional soldiers each, and some artillery, Grant’s force had “2 Compys composed of People who made their escape fm New York; they scoured the Woods & hedges” (this written by Captain William Leslie of the 17th Regiment of Foot, who was with Grant’s force). Perhaps Atlee took these skirmishers, among the first Loyalist troops to fight in the war, to be British light infantry.

But it’s also possible that Atlee assumed the British battalion troops were light infantry because of the two-rank, open order formations adopted by the entire army while they trained at Halifax in April and May of 1776. Although few of the soldiers in Grant’s eight regiments had seen combat before, most had been in the army for five or more years and were quite capable of adapting to new tactics suited to American terrain. Even though Atlee’s men weren’t fighting against light infantry, they did stand up to an extremely well trained force of professional soldiers.

Don,

As always your insight into the British tactics and order of battle is welcome! I am glad you weighed in on this. All the Continental officers were just as new to this scale of warfare as the soldiers under them and I suspect that played a part in the misidentification.

Spartans? Thermopylae?

Your confusion confuses me.

I can’t tell if you’re asking what they are or if you were wondering why they are included in this piece or why the local sources compare them to the Flying Camp? I need more to go on. =)

You start and end the article by talking about the Spartans at Thermopylae: without explaining who they are, or what happened at Thermopylae, or why it is similar to Long Island. So it is actually the readers who need more to go on.

Take a look at my article on this site, “The Myth of Granny Gates.” Almost everyone who reads it here with know about Gates, yet I put in a paragraph of biography just in case they didn’t. One cannot assume every reader will know what you know about ancient Greece. Or you might easily have omitted the reference to Thermopylae entirely.

Editors should catch this sort of thing, Will, but try as we might sometimes things get overlooked. Having edited this article, the oversight is mine – I read right through the reference to the ancient Greek battle that has become the archetype for a small force holding off a larger one, without even thinking that the reference should be clarified.

Thanks for your article. I just saw it, so these thoughts may be too late.

I place Cpt Jayne at the blockhouse on Rockaway Trail. He did warn MG Putnam, but was captured in the blockhouse, according to his obituary. Cpt.Arndt took two squads and relieved Col. Edward Hand at midnight on Martense Lane. (Some of his company testified to marching down after the firing started.) He lost 19 men and 2 sergeants in the opening skirmish. 1 sergeant died on the Jersey on 12/25/76.

They returned to the rally point which was the barn on Gowanus. BG Parsons rode up and had the 20 “wayward guards” fire a volley before he rode off. When the battalion arrived, Lord Stirling put Cpt. Hagenbach in front of Smallwood and rejoined the !st Co. and added the 3d Co. on his left, an equal division of sharpshooters.

Cpt. Hagenbach was sent with half his men to recall the reinforcement of Col. Atlee. 50 of his men stayed and were bayoneted on Battle Hill, part of the motivation for the Altar of Freedom at that spot. The rest with Cpt Hagenbach were surrounded and captured with LTC. Kachline, but Cpt. Arndt led his 80 men out to the rear and up to Hell’s Gate and back over to Manhattan and into the forts, even though his left elbow was crippled from a cannonball. Some of these men were said to be Indian fighters.

He lost more men in Ft. Washington while he and my ancestor, Sgt Philip Arndt, were getting medical attention for his elbow. Philip’s little brother, John, the drummer boy, was never seen after the Ft. Washington loss. Only 33 of the 323 mustered out, but some surely survived being prisoners, and the officers were paroled.

Philip was from Bucks County and made Durham boats. Cpt. John was a miller from near Easton, and later was a member of the first electoral college.

The scandal on Cpt. Arndt was because of the bitterness of the father of the boy who was the fifer in the company. He also thought Cpt. Arndt had deserted his command before the attack on Ft. Washington. The young fifer later escaped by swimming off a prison ship.

Cpt. Arndt wrote a family history in his Bible that concluded with the remark that there was no gratitude in the citizens of a republic for the sacrifices made by himself and others.

Hi Joe!

It would be really helpful for you to list source information! Where did you find Jayne’s obituary? I have not been able to locate it. Are you getting it from a secondary source? If so, where can I read it?

The only information I’ve found from soldiers in the Flying Camp comes from their pension applications and they are often vague. Do you have another source for this or is this family lore?

Where did you find a reference to Hagenbuch’s detachment reinforcing Atlee? Not even Atlee’s depositions after the battle mention who led what detachments.

As for the scandal–I don’t know what you mean about the bitterness of the father of the fifer. Where did you find that story? Are you perhaps confusing the story of Yost Dreisbach and the drummer in his Associator company?

“Only 33 of the 323 mustered out, but some surely survived being prisoners, and the officers were paroled.”

Where did you draw that number? That isn’t correct. If you are referring to Ardnt’s company, he did not have 323 men–that was close to the number of Kichline’s whole battalion (before Long Island–at Fort Washington, Kichline’s force was much smaller, but we don’t have exact figures so I won’t hazard a guess). Out of the remaining troops of the battalion, more than that escaped! They were folded into another company (see above). Not all of Kichline’s battalion were at Fort Washington, either. According to some depositions, some soldiers were at Fort Lee, others were placed in other duties. These words come from pension files of survivors.

Please provide some sort of source information for your claims because I’d like to vet them if they are available.

Hi Greg!

To answer your questions:

1.) According to muster rolls, Anthony Frutchy was in Arndt’s company (his name appears on the manuscript pictured here on my blog: https://historyandancestry.files.wordpress.com/2014/09/img_8199-2.jpg …He’s #56 on the muster roll–it’s abbreviated and hard to make out, but that’s him–check it out!).

2.) What evidence do you have that he perished at Long Island? I see him on the list of “killed, wounded, or taken” at Long Island, but are you certain he died there? I ask, because in 1820, a group of men met an one Anthony Frutchy’s house in Northampton County to discuss the organization of redistricting townships. Frutchy would have only been 63 years old in 1820 (if he were 19 in 1776). Unless he had a son by the same name? It’s possible, of course. But you might want to investigate this further.

3.) No known description of the flag exists for the Flying Camp–they might not have had any flag. Though since members of the Flying Camp were recruited from the Associators, it is possible they simply adapted a flag design based on their Association flags (but this is all speculative and we don’t know what the Northampton County Associators used for their flag). The Easton flag *design* dates to, at the latest, (the ‘terminus ad quem’ for the design) the 1790’s. It probably predates the 1790’s, but I don’t think it has any relevance to the Flying Camp or Associators (at least not based upon current data).

4.) Yes, men from Northampton County served in many capacities during the war. Some served early in the Flying Camp, others served as guards in Easton to protect the stores of weapons and accouterments and food sent there for protection, many were drafted into the militia after 1777, and some formed companies and marched off to join the Continental Line in various Pennsylvania Line regiments. Many even served in the Pennsylvania naval forces and manned small boats along the Delaware to protect the ferry and river towns (Easton was both).

I enjoyed your article very much. You mentioned Col. Samuel Atlee and Col. Samuel Miles, both of whom were captured at Long Island, or so I’ve read. I am interested in two men, reported as privates in Col. Miles’ and Atlee’s battalion, who were taken prisoner at the battle of Long Island and exchanged on Dec. 9, 1776. Their names were James and William Pettigrew. I am unable to find them in any list of companies under Miles’ or Atlee’s command. Would you have a source naming all the men of those companies?

Thanks for any help.

Great article! My ancestor Lewis Ettinger fought under Henry Hagenbuch initially but enlisted with the 84th in Sept 1776. I could never understand why until I read up on the Battle of Brooklyn. Really enjoyed reading the details in your article though. My only question (since most of my ancestors were Loyalists) is would it have made more sense for them to have escaped the ambush and fled to the British to enlist or captured and then volunteering to fight for the British?

………………I wonder if Gerard Butler would mind being cast as Kitchline?

Hey Bill! I’ve read up on Lewis Ettinger, actually, and plan to write on him in the future. Very interesting history.

To your question, it’s difficult to say, but according to the scant records I’ve come across, the fighting seems to have scattered everyone in every direction. When the Continentals were surrounded, many tried to hide in the swamp or tall grass around it, or fled into the woods, but in almost every instance they were captured. It doesn’t seem like the middle of combat is a place to throw down one’s arms and enlist, anyway. In fact, from the reports I’ve read, it seems like the British recruited heavily from captured Continentals after the fighting, with the period to time between capture and recruitment in some cases being within a few days.

For example, according to a Frederick Nagle’s pension deposition (Allen Township, Northampton County), the captured men of the Northampton County Flying Camp were kept in a church for a short time before being placed on a prison ship. Nagle reports that they remained on the ship until October when they were sent to Halifax, and remained there for years. Some, he said, signed papers saying they would not fight against the British and were released on parole. What’s amusing (or interesting–or both) is that, despite his deposition which says he refused to sign such papers, his story of his time on the prison ship and his subsequent confinement at Halifax might not hold water after all. On one muster role of the 84th RoF, 2nd battalion, marking the date 21 January of 1778–on assignment at Halifax!–is a name Frederick Nogle, whose enlistment is marked at ‘3 Septr 1776.’ less than a week after the battle of Long Island. Hrm…. =)

The choice has always been painted as one of necessity and rather straight forward–enlist with the British or rot on a prison ship as a POW. Maybe that was some of the incentive. But I am not convinced that it was entirely out of necessity for self-preservation. It seems to me that the bounty money to serve in a provincial unit was likely good and I suspect that given the fair beating the Continentals took at Long Island, the enticement to switch sides and join the ‘winning team’, the chance to earn good wages (or any wages at all, since the Flying camp wasn’t until years after their service in some cases), and to gain some pedigree through rank and advancement was probably appetizing to many–a point Don Hagist lays out elsewhere, if I recall.

Ugh! Roll…not role. I will blame this on lack of coffee, whether true or not. =)

Tom: Just recently came upon your fabulous work. Although I haunted the Marx Library in Easton I was not aware of your find of orginal manuscripts. Hallelulah! My ancestor, one Conrad Bloss mustered into the Flying Camp in Capt Nicholas Kern Company in Northampton County. I have followed several officers from unit as well as one Fredrich Nagle who had returned. My Conrad was never heard of again/ but Conrad Bloss is on the Oath in 1777 which might have been his son or nephew. Insufficient musters at Perth Amboy to show that he arrived as well as later musters make it almost impossible to track. Thanks for your works. Carl H. Bloss

Hey there. Actually doing some research now into your ancestor. So hopefully this helps…

The Conrad Bloss that was with the Flying Camp was captured at Long Island, along with over a dozen others, and were then recruited (under threats, most likely) into British service. They enlisted on 3 September–a few days after the battle–with the 84th Regiment of Foot/Royal Highland Emigrants and were sent north.

Bloss served throughout the rest of the war with the Regiment and shows up on returns in 1779, 1780, and I think I saw him on 1783 returns as well. Either way, after the war, he was given a substantial land grant (along with others in the regiment) and settled in Annapolis, Nova Scotia (a note next to his name indicates ‘with 2 others’).

As you say, there were many Conrad Blosses in the area all related to each other. But this Conrad Bloss is the same one from the Northampton County Flying Camp. Hope that helps.

Is there any “proof” this is the same Conrad? Yes, Tom, I have checked the Nova Scotia Archives – found the properties stated. Also there was a known Bloss presence in Nova Scotia under Lawlor’s Island (Bloss Island) – probably the Capt Thomas Bloss who brought in slaves per letter from Gov. Cornwallis. I try to work with Dick Musselman of Nazareth (you probably know him!)

Capture and desertion were part of my GPS treatise. When the officers all seemed to have returned, I began checking the Kern contingent. Several had returned home. Musters were not kept after this original listing on Jul 9, 1776. Even the oldest genealogy on the Blosses by Clinton Joel Bloss and Raymond Hollenbach make no mention of service, nor leaving the area. Thanks for your continued service and responses. Carl

Tom: is there an avenue for a direct dialogue with you and the Journal by email or phone outside this particular venue? Too much info to include in comments – I created a book on the subject but not published. Carl

Please send a message to the ed****@al**************.com address, and we’ll pass your contact information along to the author.

Tom, thanks for this great article, all your research, and for bringing more attention to the contributions of our ancestors from the Lehigh Valley. Back when I had more free time for this kind of research, I did a lot of digging into this topic myself. Samuel Wert, from Weisenberg Township in northwestern Lehigh County, the twin brother of my great-great-great-great-great-grandfather, is on Hagenbuch’s roster in Perth Amboy on August 6th and then never appears alive again. The next official reference to him is in his estate documents from spring of 1777. I don’t whether he died in battle on Long Island, at Fort Washington in November (under Baxter), in British captivity, or even from the aftereffects of captivity after release (as happened to some who simply never recovered). I have run out of ideas for how to track down exactly what happened to him during this gap between August 27th, 1776 and May 11th, 1777, so if you have any suggestions, I would be VERY grateful.

I would be happy to share with you my (rather lengthy) document about what I was able to learn about Kichlein’s riflemen and especially Hagenbuch’s company and Samuel Wert in particular. I had it posted online in the past, when I had a different host for my website. It was plagiarized/misappropriated a few times without crediting me — no big deal, as long as the news about these men’s sacrifice gets out there — and I haven’t gotten around to posting it on my new website. Just let me know where I can send it to you!

Tom,

I enjoyed reading your excellent history of the Northampton Militia’s role in the Battle of Long Island. It is amazes me that recent histories of the battle do not mention Colonel Kichline’s 1st Battalion.

I have three ancestors (John, Robert and Aaron Lyle) who are reported to have served in the Northampton Militia at the Battle of Long Island. I did find Robert Lyle listed on Captain Arndt’s company in the muster at Perth Amboy after the fighting ended. However I have not found any record of John and Aaron Lyle.

Please advise if you have found any information about them.

Thanks,

Jim Kessling

Lt. Colonel Peter Kachlein only was one of two Flying Camp commanders under Lord Stirling at the Battle of Long Island. The other commander was Lt. Colonel Nicholas Lutz who forces suffered severely. He was both wounded and captured. If you’re going to mention one, you should mention them both.

Do you have any records of desertion from the Northampton company’s, particularly Arndts? I am trying to work on a flying camp impression and would like to refine my impression from its current state, however I have had a hard time finding any reports of how the unit looked

Hi Thomas,

Desertion reports for the Flying Camp are rare; I have none from the Northampton County companies (though a few from the other battalions yields little information).

To play it safe, maybe consider a civilian impression and just add the military accouterments (cartridge box, canteen, haversack, knapsack, etc..). But without information it will all be speculative. Sorry I can’t be more help!

Do you have any information of a Jacob Singley serving in Col. Nicholas Kern Battalion. I am doing research and believe that Jacob married a Cornelia Kern, daughter of Nicholas. Any help would be appreciated.

Tom: Good to get back again: Raymond Hollenback in his transcription of the History of Heidelberg Church (Lehigh County) speaks of a known group of men serving in the Flying Camp? His listing doesn’t even include a Conrad Bloss/ traitor or not? Did you ever find this one? Still trying to track down info about my Conrad Bloss altho you seem quite sure the Nova Scotia guy is one and the same.

Oh, saw acknowledgement in Rebecca Janney’s Forks at Easton series – great. Just like walking in their shoes! Carl

Tom,

Fascinating stuff. Has your research disclosed positions of PA and MD troops in the vicinity of the Vechte-Courtelyou House (OSH) during the final phase of defense, specifically Atlee’s battalion? I would appreciate receiving your reply direct to my email address as I am deeply engrossed in a mapping project.

Hi Tim,

I haven’t looked too closely, but I am interested as well in what you’ve uncovered. Please keep us posted.