“The Press, Watson, is a most valuable institution, if you only know how to use it,” said the fictional detective Sherlock Holmes.[1] Benjamin Franklin had a lifetime of experience with the Press and knew well how to use it.

In the spring of 1782, five months after Yorktown, Franklin was in Paris working on the complex diplomatic problems involved in negotiating a peace treaty among Britain, France, Spain, the Netherlands and the United States. Franklin was seeking, among other things, reparations to the United States citizens who had lost their lives and property. Appealing to the British government would likely prove unsuccessful. So Franklin aimed at reaching the British citizens.

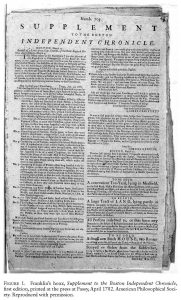

Franklin’s weapon used in this propaganda warfare operation was the Boston Independent Chronicle newspaper. With great skill Franklin created a counterfeit issue of the newspaper,[2] carrying articles written by himself. He intended to have this fake newspaper very discreetly put into the hands of British newspaper editors who he hoped would reprint the articles in their papers. Reprinting articles was common at the time. If successful, his phony articles would then be read by huge numbers of British citizens.[3]

The hoax newspaper purported to be a Supplement to the Boston Independent Chronicle, dated “Boston, March 12.” The supplement, spuriously identified as “Numb. 705,” consisted of one sheet of paper with two articles plus advertisements making it appear in all respects to be a true supplement to the legitimate newspaper.

The primary article in the hoax supplement concerned wartime atrocities by Indians at the behest of the British. The secondary article purported to be a letter from John Paul Jones and was also aimed at the British public. The “Jones” letter denounces the British policies that put captured American sailors in prisons under deplorable conditions with little hope of exchange. This letter did not have the gory fascination of the Indian atrocities letter and received little attention.

The Indian atrocity article appeared to be a legitimate letter from an American militia officer, Captain Samuel Gerrish, to his commanding officer describing a captured letter and packages which had been intended for the British governor of Canada. The officer wrote that he was “struck with Horror to find among the Packages, 8 large ones containing SCALPS of our unhappy County-folks, taken in the three last Years by the Senneka Indians from the Inhabitants of the Frontiers of New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Virginia, and sent by them as a Present to Col. Haldimand, Governor of Canada, in order to be by him transmitted to England.”

The article continued with an alleged letter from a British agent accompanying the eight packages which described their contents in grisly detail:

At the Request of the Senneka Chiefs I sent herewith to your Excellency, under the Care of James Boyd, eight Packs of Scalps, cured, dried, hooped and painted, with all the Indian triumphal Marks, of which the following is Invoice and Explanation.

No. 1. 43 Scalps of Congress Soldiers killed in different Skirmishes; these are stretched on black Hoops, 4 Inches diameter; the inside of the Skin painted red, with a small black Spot to note their being killed with Bullets. Also 62 of Farmers, killed in their houses; the Hoops red; the Skin painted brown, and marked with a Hoe; a black Circle all round, to denote their being surprised in the Night; and a black hatchet in the Middle, signifying their being killed with that Weapon.

No. 2. Containing 98 of Farmers killed in their Houses…

No 3. Containing 97 of Farmers, killed in their fields….

No. 4. Containing 102 of Farmers…18 marked with a little yellow flame, to denote their being of Prisoners burnt alive, after being scalped, and their Nails pulled out by the roots and other Torments: one of these latter supposed to be of a rebel clergyman, his Band being fixed to the Hoop of his Scalp. Most of the Farmers appear by the hair to be young or middle-aged Men; there being but 67 very grey Heads among them all…

No. 5. Containing 88 scalps of Women; hair long, braided in the Indian Fashion, to shew they were Mothers;….17 others, hair very grey…no other Mark but the short Club…to shew they were knocked down dead, or had their Brains beat out.

No. 6. Containing 193 Boys’ Scalps of various Ages…

No. 7. 211 Girls Scalps, big and little…..

No. 8. This package is a Mixture of all the Varieties above mention’d, to the number of 122; with a box of Birch Bark, containing 29 little infants Scalps of various sizes; …a little black Knife in the middle to shew they were ript out of their Mothers’ Bellies.

Included along with the packages was a “Speech” from the Chiefs directed to the British Governor of Canada requesting that he “send these Scalps over the Water to the great King, that he may regard them and be refreshed; and that he may see our faithfulness in destroying his Enemies, and be convinced that his Presents have not been made to ungrateful people.” In addition the chiefs wrote that, “we are poor, and you have Plenty of every Thing. We know you will send us Powder and Guns, and Knives and Hatchets: but we also want Shirts and Blankets.”[4]

Of course, the use of Indian allies was commonplace in past wars. However, Franklin wanted the horrors of war, and especially the horrors of war against the civilian population, brought home to the British citizens. In addition, he wanted to show that the British government did not care about their Indian allies. It was their purpose to use the Indians to kill colonial Britons and in addition to make the Indians dependent upon the British for their supplies, even to the point of “Shirts and Blankets.” This state of dependency was something that the colonists had claimed that the British were trying to do to the colonies.

In order to get the supplement into the hands of British printers Franklin sent copies to several correspondents. One he sent to John Adams, in Amsterdam, admitting that the supplement might be untrustworthy but that the scalping issue was very real. He also sent copies to Charles Dumas, the American agent in the Netherlands, John Jay in Madrid and James Hutton, a Moravian in England. His letters gently suggested that it would be useful if the supplement was printed in England.[5]

The “scalping” letter from the supplement was published in London General Advertiser and Morning Intelligencer, June 29, 1782.[6] Much of it was also published in The Remembrancer; or, Impartial Repository of Public Events, (London: J. Almon) in 1782.[7]

In North America the “scalping” letter was published dozens of times beginning with the New Jersey Gazette (Trenton, NJ) on December 18, 1782. The Gazette noted that it received the piece from the London General Advertiser and Morning Intelligencer of June 29, 1782, which cited the Boston Independent Chronicle. Clearly, the New Jersey Gazette assumed it was publishing a news event. In fact, it wasn’t until over 70 years had passed before the October 4, 1854 The State Gazette (Trenton, NJ) described the scalping letter as a Benjamin Franklin hoax.[8]

The repulsive and gruesome hoax perpetrated by Franklin was propaganda skillfully designed and executed to demonize the former British ministry in the eyes of the British public. The current ministry would find it hard, facing such images, not to give in to American claims at the peace negotiations.[9]

/// Featured Image at Top: 1767 Portrait of Benjamin Franklin by David Martin. Current Location: White House

[1] This quotation appears in the short story The Adventure of the Six Napoleons, published April 1904.

[2] Franklin had a complete printing shop as his position required that he print passports, forms and official documents.

[3] The best authority on the Supplement hoax is Carla Mulford, “Benjamin Franklin’s Savage Eloquence: Hoaxes from the Press at Passy, 1782,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 152, No. 4, (December 2008), 490-530.

[4] The complete transcription of the Supplement is available at: Founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-37-02-0132.

[5] Mulford, Hoaxes, 502, 516.

[6] London General Advertiser and Morning Intelligencer, June 29, 1782.

[7] Mulford, Hoaxes, 525.

[8] Mulford, Hoaxes, 529.

[9] Carl Van Doren, Benjamin Franklin, (New York: Viking, 1938), 673.

12 Comments

Maybe it’s just the newspaper geek in me, but I think this is one of those “better than fiction” stories of the American Revolution. Good stuff!

Here’s another example of something I never knew about Franklin coming to light! Thank you, Hugh, for an enlightening, well-researched story.

Franklin continues to amaze me, and now, who knew that more than a century before William Randolph Hearst engaged in “yellow journalism” to affect world outcome (The Spanish American War), Franklin sort of beat him to it! I’m not surprised.

Years ago when I was the editor of The Brigade Dispatch, the historical publication of the Brigade of the American Revolution, a contributor submitted this “letter” by Captain Gerrish as an example not only of the horrors of war but of the material culture of scalps as trophies. I was completely taken in and published it; fortunately, a wiser reader submitted a correction for a subsequent issue.

Researchers are always wise to use caution even when approaching a primary source, because truth wasn’t always on a writer’s agenda.

Don stated another basic truth in research work: just because it’s old doesn’t necessarily mean it’s real.

Don, you might want to do a follow-up article on Franklin’s 1777 falsified letter regarding “blood money” paid to a German prince for his dead and injured mercenary soldiers. He was a masterful manager of covert activities during the war and certainly deserving of the decision to designate him as a “Founding Father”( for covert action) of American intelligence.

Ken,

The article you suggest is in the works and has been for quite some time. I hope to bring it to you, “soon.”

Very glad to hear that, Hugh. I was afraid I’d have to write it, and it’s already been proven that I can’t tell facts from propaganda.

It’s an honor to be among those fooled by Ben Franklin 🙂

As Franklin knew that the scalping murders committed during the war were in fact a widely known issue in America, his use of this knowledge to achieve reparations from Britain is yet again a measure of his genius and cunning! I wonder if this fake publication had any influence on the British during the peace negotiations. I would imagine that some of the British citizenry were outraged as by that time they were also fed up with the war.

Thanks for another fascinating story on Ben Franklin.

John Pearson

I found that Franklin’s fake newspaper was also featured in the July 6, 1782 issue of the Norfolk Chronicle (Norfolk, England), the July 8, 1782 issue of the Salisbury and Winchester Journal (Wiltshire, England), and the July 9, 1782 issue of the Cumberland Pacquet (Cumbria, England).

In the spirit of April 1 and considering the fact that Franklin distributed this piece of propaganda in April 1782, I think it’s safe to call this one of the most historically significant April Fool’s gags. Even Mental Floss magazine thinks so: http://mentalfloss.com/article/62668/6-ben-franklins-greatest-hoaxes-and-pranks

He was a figure of genius and innovation, but worship of his ability to deceive and inflame politics through propaganda might be pause for thought. One wonders if he was indeed a ‘spy’ and rebel propagandist why his visits to the infamous Hellfire Club in London were not molded into a stunning political condemnation of the English aristocracy! Or why his stunning love of what was in reality English style puritan republican liberty did not fully extend to slavery or the preservation of Indian lands before, during and after the War of Independence. He greatly benefited from slave labour throughout his life, although he did release his slaves before his death, he was by this time no longer reliant on them. He did not even address the issue in 1787. Yes he advocated in essays, but cautiously. He was unusual among the so called founding fathers, more likable, but not disconnected. Of course the hypocrisy of the rebel Anglo-Americans (politically and often personally) is often left unexplored or excused, and his ‘golden generation’ never seems to move beyond the established US hagiography.

Adam,

You are right on the money regarding the gross hypocrisy of so many liberty seeking Americans including the Founders. Perhaps Alexander Hamilton is the only Founder who truly appreciated the horrors and cruel hypocrisy of slavery and who allegedly and anonymously wrote Jefferson and Madison in February of 1791 “Who talk most about liberty and equality…? Is it not those who hold the bill of rights in one hand and a whip for affrighted slaves in the other?”

Unfortunately, in order to gain support for new US Treasury measures being considered he went virtually silent on the slavery issue.

John Pearson