The American army during the Revolution consisted of three basic varieties of units—militia, state troops, and the Continental Army. Beginning with the earliest communities, militia served as a short-term local defense force raised by towns. The men who responded to the call on April 19, 1775, and laid siege to the British in Boston came from militia companies. Very soon after the war of words became a war of bullets, the individual states began to form units intended for much more than militia-style service. These state troops would serve longer terms and in a wider area. Within a few weeks, the Continental Congress took on the responsibility for supplying and paying the loose army around Boston and soon after began to take on the state troops. The Continental Army—those units paid by Congress—had been born.

Please note that the following discussion deals with only the pay of the regular infantry. Many other branches of the military—light infantry, artillery, naval—received pay at different rates. Nor does this article address pay for men aside from regimental fighting soldiers such as general officers, staff, medical personnel, etc.

Pay rates for Continental soldiers—and militia ordered out to serve with the Continental units—evolved over the first several months of the conflict. In June, 1775, Congress called for the raising of ten rifle companies and, in the process, set the rates for ranks up to captain (each man to provide his own arms and clothing). By the end of July, rates for other commissioned officers had been settled upon and the army around Boston now had a defined pay scale.

Table 1.—Initial Monthly Pay Rates.[1]

|

Rank |

Dollars[2] |

|

Colonel |

50 Advertisement |

|

Lieutenant Colonel |

40 |

|

Major |

33⅓ |

|

Captain |

20 |

|

Lieutenant |

13⅓[3] |

|

Ensign |

10 |

|

Sergeant |

8 |

|

Drummer or trumpeter |

7⅓ |

|

Corporal |

7⅓ |

|

Private |

6⅔ |

Even though rates supposedly had been settled, an unofficial debate continued amongst members of Congress. Exhibiting a bit of foresight, John Hancock wrote to Elbridge Gerry in June, 1775, saying that, “Those ideas of equality, which are so agreeable to us natives of New-England, are very disagreeable to many gentlemen in the other Colonies.” He explained that many felt the enlisted men (private through sergeant) received too much and the officers received too little. Hancock expected that those in Congress who held that opinion “would have their own way” and the pay would eventually be changed to reflect their view.[4]

Indeed, with an army-wide reorganization in November, 1775, Congress increased the pay of company level officers—captain to 26⅔, lieutenant to 18, and ensign to 13⅓ dollars.[5] In October of 1776, “as a farther encouragement for gentlemen of abilities,” all commissioned officers received increases but, as Hancock had predicted, rates for enlisted men remained the same.[6] Reflecting the class structure of society, the new pay scale deliberately fashioned a considerable gap between the enlisted men and commissioned officers—an ensign earned two-and-a-half times that of a sergeant. This gap remained in effect for the remainder of the war.

Table 2.—Final Monthly Pay Rates.

|

Rank |

Dollars |

|

Colonel |

75 |

|

Lieutenant Colonel |

60 |

|

Major |

50 |

|

Captain |

40 |

|

Lieutenant |

27 |

|

Ensign |

20 |

|

Sergeant |

8 |

|

Drummer or trumpeter |

7⅓ |

|

Corporal |

7⅓ |

|

Private |

6⅔ |

To serve as an enticement for an individual to join the army, Congress, states, towns, and even individuals offered a bounty—a one-time payment of money or a grant of land—received upon enlistment. The amount varied considerably depending on when, where, who paid, and even what the soldier brought with him when he joined—firelock, blanket, etc. With only limited amounts of specie (gold, silver, and copper coinage) circulating in North America and a widespread distrust of paper money printed by the individual colonies and, later, Congress, payment of a cash bounty often proved difficult. As a result, some men received their bounty in the form of notes redeemable with interest at a future date. The abundance of land available in the expansive wilderness of the colonies made that commodity a common substitute for cash and many men received acreage instead of cash. In one form or another, soldiers received a bounty upon joining. Many, however, lost out on much of the value of it when they sold their notes or land warrants at a significant discount for ready cash, particularly in the later years of the war when high inflation and a suffering economy made paper money in any form nearly worthless.

By 1781, the staggering inflation rate resulted in 167½ Continental paper dollars equaling one dollar in specie, giving rise to the phrase, “not worth a Continental.”[7] Many individuals and businesses refused to accept the paper money or any bills of credit that promised payment at a later date. As early as February, 1777, Congress and the states addressed the problem by taking measures intended to prevent the depreciation of the currency.[8] The efforts generally failed and, in an attempt to assuage the frustrations of the army, the soldiers received certificates for additional pay intended to make up for the depreciation in value of their initial pay.

Efforts to settle pay issues continued long after the war ended and the men had left the service. It is to the credit of those men who formed the national government of the United States that they continually endeavored to see that the Continentals who put their lives on the line received pay for their sacrifices. They could easily have simply defaulted on the debt but chose not to. It is also to the credit of the men who continued to serve in spite of often going long periods without pay or being paid in near worthless paper. It is evidence of a sense of commitment to an idea of a new type of government, a commitment for which we should be proud of those men who formed the United States.

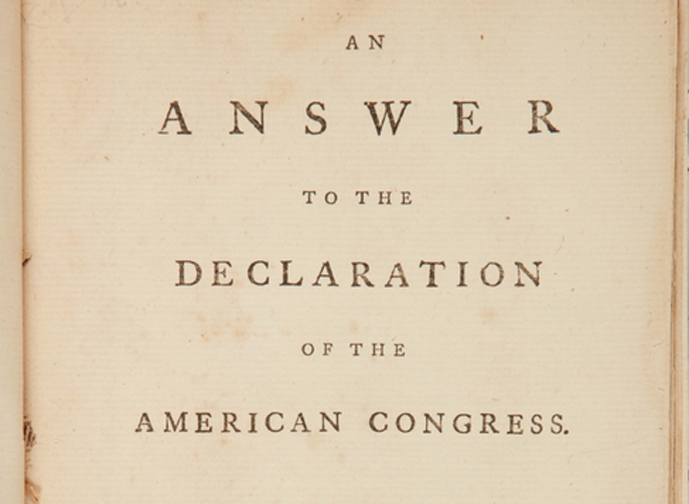

[Featured Image at Top: A Continental one-third dollar note printed by Hall and Sellers in Philadelphia, 1776. Click here to view more examples of Continental currency. Source: Teacher Resources, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco]

[1] “Proceedings 14 June 1775.” National Archives and Records Administration Papers of the Continental Congress, “Rough Journals, 1774-89,” 1:85. From fold3, Continental Congress—Papers. http://www.fold3.com/image/1/451905/ (accessed November 23, 2012). Hereafter noted as Papers.

[2] Throughout the period of this discussion, Congress used Pennsylvania currency for conversion—₤1 = 2⅔ dollars or 1 dollar = 7s6p. Twenty shillings made up one pound and 12 pence equaled one shilling. Also, note that the dollar was divided into 90ths rather than the modern 100ths, which made it logical to include thirds of dollars in the pay rates.

[3] In October, 1775, Congress resolved to pay 1st and 2nd lieutenants at the same rate. “Proceedings 2 October 1775.” Papers, “Rough Journals,” 1:156. From fold3, Continental Congress—Papers. http://www.fold3.com/image/1/452353/ (accessed November 23, 2012).

[4] John Hancock to Elbridge Gerry, 18 June 1775, reprinted in Peter Force, American Archives: Fourth Series (Washington, D.C., M. St. Clair Clarke and Peter Force, 1839), 2:1020.

[5] “Proceedings 4 November 1775.” Papers, “Rough Journals,” 1:190. From fold3, Continental Congress—Papers. http://www.fold3.com/image/1/452538/ (accessed 6 June 2013).

[6] “Proceedings 7 October 1776.” Papers, “Rough Journals,” 5:56. From fold3, Continental Congress—Papers. http://www.fold3.com/image/1/456227/ (accessed 12 December 2013).

[7] Jack P. Greene and J.R. Pole, eds. The Blackwell Encyclopedia of the American Revolution (Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishers, 1994), 364.

[8] “Proceedings 15 February 1777.” Papers, “Transcript Journals, 1775-79,” 6:1243. From fold3, Continental Congress—Papers. http://www.fold3.com/image/1/402701/ (accessed 24 July 2012).

2 Comments

This is a very good article. I am going to insert the pictures and the website from the references into my chapter on the Revolution for my American History to 1865 course. Good work, Michael! I have made this site a reference site for students who write their research papers on events in this era.

I am honored that my work contributed something to your course. Be sure the students understand that what I came up with is just the basic rates for Continental battalion infantry. All sorts of variations go off from there and those can be a fascinating and convoluted study in themselves. I initially planned to include other information but the article would have been much too long and involved. Nothing’s simple when it comes to money.