While the War of American Independence was won on the Eastern seaboard by American and French battling the British, the future of the United States was determined in small, seemingly inconsequential battles in the western theatre. The battles west of the Appalachian Mountains would shape the destiny of the American nation by determining what land would become the United States during the Paris peace negotiations. The battle of St. Louis, May 26, 1780, was important for this reason. The ironic part is that there were only a handful of American and British individuals involved in the pivotal battle. Instead, Native Americans, French settlers and traders, fought against Spanish soldiers, colonists, merchants and black slaves in the battle.

The town of St. Louis was established by French traders in 1764 eighteen miles south of the confluence of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers and was to be the main trading post for the region.[1] The town of St. Louis became Spanish when the French gave the area to Spain in exchange for Spanish losses incurred while fighting in support of the French during the French & Indian/Seven Year’s War.[2] The new Spanish overlords sent few troops, few supplies, and few funds to maintain the colony or its defense. When the American Revolution broke out St. Louis was a community of around 900 people, most of whom were French with a few Spanish soldiers. They were greatly outnumbered by various Native American tribes which the traders had been supplying with firearms in exchange for furs. This act caused strife many miles away as these tribes used those firearms to invade the territories of other tribes, two of them being the Sioux and Winnebago in the modern regions of Minnesota, Iowa, and Wisconsin.[3]

Across the Mississippi, on the east bank, the British had taken possession of the region from France, and much like the French and Spanish sent few troops to the western frontier. After a period of learning how to pacify the local tribes via the use of presents and weapons, the British enjoyed a much better relationship with various tribes, two of which were the Sioux and Winnebago. For much of the history of North America, the French, Spanish, British, and soon to be Americans played the Indians against each other while the Indians did the same to them. In the case of the American Revolution in the western lands, the Indians would supply the majority of the manpower both the American and the British war aims. In the case of the Spanish, allied with the Americans, this meant they would be greatly outnumbered by Indians in the St. Louis area.

Across the Mississippi, on the east bank, the British had taken possession of the region from France, and much like the French and Spanish sent few troops to the western frontier. After a period of learning how to pacify the local tribes via the use of presents and weapons, the British enjoyed a much better relationship with various tribes, two of which were the Sioux and Winnebago. For much of the history of North America, the French, Spanish, British, and soon to be Americans played the Indians against each other while the Indians did the same to them. In the case of the American Revolution in the western lands, the Indians would supply the majority of the manpower both the American and the British war aims. In the case of the Spanish, allied with the Americans, this meant they would be greatly outnumbered by Indians in the St. Louis area.

In 1778 Fernando de Leyba, the Lt. Governor of Louisiana arrived in St. Louis, and his actions would have major repercussions far beyond his own intentions. After the American George Rogers Clark’s successful invasion of the western British held areas de Leyba gave Spanish supplies to Clark. This aid proved decisive in keeping the captured territory in American hands until the war ended. The Spanish aid to Clark did not go unnoticed and the British prepared an offensive designed to capture both St. Louis.[4] When Spain entered the global conflict against Britain in 1779, St. Louis was not militarily prepared. De Leyba had few soldiers, most of the European inhabitants were French, and they were massively outnumbered by the local, mostly unfriendly, Indians. He organized a local militia of over 200 men, few of who had any military experience, and most of which would be gone at one time or another during the year in their occupation as boatmen, farmers, hunters, merchants, and traders.[5]

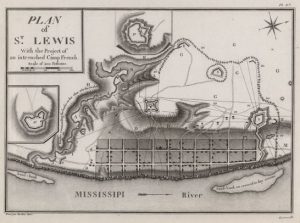

Word reached de Leyba early in 1780 that a British and Indian force was moving against St. Louis. His lack of funds, manpower, and time necessitated a scramble to throw up defensive lines. One stone tower was constructed along with more than a mile of trenches dug in front of the village. [6] He gathered every man he could to augment his forces by pulling isolated detachments into town. The cannon were placed in the tower, infantry were in the trenches as they awaited the British attack.[7]

The British force was almost all composed of Indians. The Sioux and Winnebago tribes who had been victims of the tribes equipped with Spanish muskets eagerly joined the British in return for firearms and promises of captured enemies. Most of the few Europeans in the force were actually French Canadians led by a former British officer, Emanuel Hesse. Hesse was now a fur trader, and he and the other Canadians were promised the license to the fur trade of the region along with the chance to settle scores with the Spanish who had been engaged in a long running trade war with the British for over a decade.[8] Few actual troops were present with most whites being militia and the bulk of the forces being Indians.

The Indians consisted of over 200 Santee Sioux, a group of Chippewa, plus large groups of Winnebagoes, Menominees, and some warriors from other tribes. Along the way they added 250 Sauk and Fox warriors who were cajoled or forced to join the invasion even though they were nominally allies of the Spanish.[9] As with many of the various plans hatched in London by men who had no real idea of the scale of North America, this grand strategic campaign failed to be executed.[10] The proposed British three pronged attack failed to materialize. The force from the Upper Mississippi divided itself into two attacking groups, one aimed at St. Louis on the west side of the river and the other aimed at Cahokia on the east side and launched their assaults on May 26th.

Despite the advance warnings of the impending invasion, the villagers were out in the fields around the town working their crops. The first warning shots were fired and men scrambled for their arms before dashing to the trenches. There was a mad dash for the village gates as several hundred Indians came down upon them howling and firing their muskets. Many villagers failed to reach safety before being overrun by the warriors who were eager for captives and scalps. As unprepared as the village was, the Spanish soldiers quickly brought their cannon into action and began firing upon the attackers. This was a great shock to the Indians as they had not expected any cannon or any type of defensive fortifications. The charge across the prairie and fields faltered as the roaring cannon, and growing crackle of musket fire from the trenches began taking a toll on the attackers.[11]

The Sauk and Fox tribesmen pulled back immediately as they had the least amount to gain from the assault. This lack of trust among the tribes was the single biggest reason why the assault failed. The Dakota and Winnebago didn’t trust the Sauk and Fox, and didn’t want to take the chance of getting caught between two enemies. The handful of British and French Canadians failed to convince their allies to continue the fight by not assisting in a frontal assault on the trenches and after five hours the attack was over. The Indians withdrew back to the mouth of the Illinois River to await the attackers of Cahokia, whose attacks had also failed, before returning home.[12]

The St. Louis attackers did not, however, go home empty handed. They had killed fourteen whites and seven slaves, wounded seven more people, and captured 25 people. In addition 46 more were captured on the march to St. Louis. Some of these captives would be ransomed or exchanged. The success of the Spanish defense was due in a large part to the five cannon mounted in the tower as well as the defensive trenches which enabled the Spanish to concentrate firepower while behind cover. De Leyba’s leadership, although severely contested in some accounts, was also responsible as he forbade any attacks upon the Dakota and Winnebagos as they mutilated the corpses of the dead left on the field trying to draw the Spanish battle outside their trenches.[13]

This seemingly inconsequential battle of the War of American Independence would have serious implications in the years ahead. The Spanish had repulsed a British led invasion and later would counterattack taking a force far into the north capturing Ft. St. Joseph (Michigan) in January of 1781, although only holding it for a day before withdrawing back to St. Louis. The Spanish used the victory as the basis to claiming the region during peace negotiations.[14] When the warring nations began to discuss peace Spain held the western side of the Mississippi River while the Americans held much of the Illinois-Ohio Valley. In addition, the Spanish had captured the British ports along the Gulf of Mexico along with all of Florida.[15]

Had the British taken St. Louis it is probable the victory would have swung additional Indian tribes to their side. St. Louis would have given the British an excellent base to launch attacks or supply Indian raids against the pitifully small Americans forces north of the Ohio River. Their possession of the western lands would have benefitted the British in the Paris peace negotiations. Instead of giving up claims to the vast lands east of the Appalachians, the British would almost certainly have kept possession of them. The result would have been the bottling up of American settlers in the thirteen states and denying western expansion to the new nation. The US would have developed differently than it did which makes the small and almost forgotten Battle of St. Louis extremely important in the grand scheme of American history.

Featured image: Photograph of a mural entitled Indian Attack on the Village of Saint Louis, 1780, depicting the Battle of St. Louis. Source: Wikimedia Commons user Magnus Manske

[1] James N. Primm, Lion of the Valley: St. Louis, Missouri (Boulder: Pruett Publishing, 1981), 9.

[2] Colin G. Calloway, The Scratch of a Pen: 1763 and the transformation of North America (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 133-149.

[3] A.P. Nasatir, “Anglo-Spanish Rivalry on the Upper Missouri,” in The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 16, No. 3 (Dec., 1929), 362.

[4] Carolyn Gilman, “L’Annee du Coup: The Battle of St. Louis, 1780,” in The Missouri Historical Review, Vol. 103, No. 3, (April 2009), 141.

[5] Primm, Lion of the Valley, 42.

[6] The stone tower was located at approximately the intersection of modern Walnut Street and 4th Street; midway between Busch Stadium and the Gateway Arch. The trench ran along 4th Street and turned northeast at Edward R. Jones Dome and continued to the river.

[7] Stella M. Drumm, ”The British-Indian Attack on Pain Court (St. Louis)” in Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1908-1984), Vol. 23, No. 4 (Jan., 1931), 644.

[8] Gilman, L’Annee du Coup, 144.

[9] Primm, Lion of the Valley, 44.

[10] Gilman, L’Annee du Coup, 195-196.

[12] Gilman, L’Annee du Coup, 204-205.

[13] Primm, Lion of the Valley, 45-46.

[14] Mark M. Boatner, Encyclopedia of the American Revolution (Mechanicsburg: Stackpole Books, 1994), 385.

[15] Jonathan R. Dull, A Diplomatic History of the American Revolution (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985), 110-111.

9 Comments

Jimmy, this is a timely piece for me. I just finished reading Patricia Cleary’s “The World, the Flesh, and the Devil: A History of Colonial St. Louis” (University of Missouri Press, 2011) to help me with ideas for my book.

I noticed that you did not include it in your citations. If you have not read it, I recommend it. It is an interesting book with a chapter on the Battle of St. Louis. Cleary also discusses the St. Louians’ interactions with the Americans just before the battle and after the Revolution.

Thanks Liz. I am at MACC teaching at the moment, (test time!) so I don’t have my notes here, but I do think I saw some references to that work on a website about St. Louis. There is a historical group in St. Louis that has been doing some planning for a commemoration of the battle later this year. When I get back to my office this evening I will put a link up to them. I didn’t have that book available and used an older work by James Primm. Carolyn Gilman’s two part article in the Missouri Historical Review was outstanding and really goes into a lot of depth on the entire affair. It is around 40 some pages total.

I had dug up several sources that dated back to the 1920s era and found it interesting when I looked at Gilman’s sources and found she used them as well. There is not a great deal of information on the battle itself, but she included a historiographical look at how the battle was interpreted over time which was fascinating in itself. It really showed how important using multiple sources and involving context in historial analysis is.

I’m glad you liked the article. I have friends in St. Louis who walk over the spot where the stone tower was every day and had no clue what took place there.

Liz,

I didn’t find her name on anything after all. I am linking the commemoration website information though. I know I’ve seen that name, but I just don’t remember where. It must have been in connection with something else. http://www.battleoffortsancarlos.org/

Thanks so much for this! I’m a direct descendant of Jean Batiste Sale dit Lajoie, a founder of St. Louis, who chose the location for the trading post, and the Spanish woman he rescued from the Comanche (I believe) in the area of Taos, NM. Her name was Maria Rosa Jacquez Villalpando. They returned together and were married in St. Louis. Sappington House in Kirkwood(?) is preserved as the home where they lived out their lives. She is said to have survived to age 104 or 107! Her story is included in the history of Taos.

One of her sons was said to have fought to defend the city in the Battle of Fort San Carlos, or Cahokia.

Another of their descendants was Judge Wilson Primm, early historian of St. Louis.

I would love to learn more!

Hi Marie Quinn Flanagan,

I am also a direct descendant of Maria Rosa Villalpando. I’ve read her story and find it fascinating. I’ve visited the Arch grounds and I can only imagine how she was able to witness and survive the The Battle of St Louis in 1780.

My understanding is that Spain ended up putting up more troops than France in North America during the war of independence.

St. Louis MO was founded by Pierre Laclède Liguest and his 14 year old stepson (Rene) Auguste Chouteau (my 5x great grandfather). Laclede (who was sponsored by New Orleans merchant Gilbert Antoine de Saint-Maxent) chose the site and put Auguste in charge of the planning and the building of the trading post and other buildings. Laclede died soon after while on a supply run from New Orleans, so the whole project fell on the young Auguste. His younger half brother Pierre Chouteau came a short time after along with his other half siblings and mother, Madame Marie-Therese Bourgeois Chouteau.

Jimmy:

Nice article. Six years late in my seeing it, however, always great to locate some new articles! If you haven’t seen it, you might want to consider “At the Crossroads: Michilimackinac During the American Revolution”, Mackinac Island: Mackinac Island State Park Commission, 1978 (with reprint editions) by Dr. Keith Widder and the late Dr. David Armour, both longtime historians (Widder now retired) for the Mackinac Island State Park Commission (Mackinac State Historic Parks). This has a nice account on Hesse and the St. Louis Raid (pp. 135, 137-139, 143) from primary sources and relates further information about the background planning from British Governor-Superintendent/Fort Mackinac Commander Patrick Sinclair and the involvement of Objibwa (Chippewa) chief Matchekewis, former French officer, then British militia officer Charles Langlade and others. You were correct in that there were very few actual British soldiers in the expedition/attack force-Widder/Armour mention that the primary sources mention only three (3) British soldiers accompanied them. However, as we all know, that was essentially the situation for all the expeditions and raids on the western theater of the war in Ohio, Kentucky, Illinois, Tennessee, etc.

BTW, St. Louis is a neat city and I, too, have enjoyed walking downtown where the original settlement and stockade was. BTW, my late father was one of the architects who worked for and helped design the St. Louis Gateway Arch under famed architect Eero Saarinen. I still have some of dad’s drawings from that and photo 35mm slides from its final completion. Too bad Saarinen did not live to see that project come to fruition. Anyway, thanks for a nice article

The TV show “what history forgot”, this is what they forgot.

The Battle of St.Louis,Cahokia, Battle of Baton Rouge,Natchez,Mobile, Pensacola, plus many naval battles.

“it’s too coincidental, to be a coincidence”

Yogi Berra