Myth:

Toward evening on December 16, 1773, Francis Rotch, beleaguered owner of one of the tea-laden ships in the Boston Harbor, announced to thousands of people assembled at Old South Meeting House that Governor Hutchinson remained firm and would not allow his vessel to return to Britain with its cargo still on board. At that moment, Sam Adams climbed on top of a bench and announced to the crowd: “This meeting can do nothing more to save the country.” This was the “signal” for the “Tea Party” to begin. “Instant pandemonium broke out amid cheers, yells, and war whoops,” a modern account declares. “The crowd poured out of the Old South Meeting [House] and headed for Griffin’s Wharf.”[1] Many and perhaps even most standard narratives of the Boston Tea Party repeat this tale, including my own People’s History of the American Revolution, published in 2001, and the reenactment staged annually at Old South Meeting House, as reported recently on this site.

Busted:

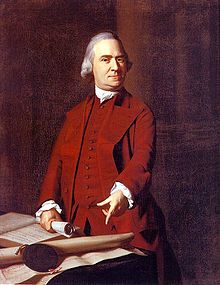

Although Samuel Adams [nobody but his enemies called him “Sam” in his lifetime] did in fact state “that he could think of nothing further to be done,” this was not some pre-arranged “signal” for the Tea Party to begin, for the timing was way off. According to eyewitness accounts, Indian yells were not heard until later, and even then Adams and others tried to quiet the crowd and continue the meeting.

xxx

Let’s look at the evidence. We have several contemporaneous accounts:

*After Rotch reported that the governor would not let him return the tea to England, “Mr. Adams said that he could think of nothing further to be done. About 10 or 15 minutes later, I heard a hideous yelling in the Street at the S. West Corner of the Meeting House and in the Porch, as of an Hundred People, some imitating the Powaws of Indians and other the Whistle of a Boatswain, which was answered by some few in the House; on which Numbers hastened out as fast as possible while Mr. Adams, Mr. Hancock, Dr. Young with several others called out to the People to stay, for they said they had not quite done.…Mr. Adams addressed the Moderator in these Words, ‘Mr. Moderator, I move that Dr. Young make (or be desired to make) a Speech’—which being approved of, Dr. Young made one accordingly of about 15 or 20 Minutes Length…. [W]hen he had done, the Audience paid him the usual Tribute of Bursts of Applause, Clapping, etc. and immediately Mr. Savage (the Moderator) dissolved the Meeting.”[2]

- “An Indian yell was heard from the street. Mr. Samuel Adams cried out that it was a trick of their enemies to disturb the meeting, and requested the people to keep their places.”[3]

- “An Impartial Observer” reported in both the Boston Evening Post and the Boston Gazette of December 20 that after the first “war-whoop” from the doorway, “silence was commanded, and a prudent and peaceable deportment again enjoined.” A similar report appeared in the December 21 issue of the Essex Gazette (Salem, MA) and the December 23 issue of the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Weekly News-Letter.

The story that emerges from the evidence reverses the mythological one. There was a considerable gap between Adams’s statement and the war-whoops, and yet another gap between that disruption and the end of the meeting. Some have suggested that Adams and other leaders wanted to continue the meeting to provide themselves with cover; since they were seen in public, they could not be accused of participating in the vandalism. Even if so, the historical record gives no indication that Adams’s words were some pre-arranged signal to rush toward the wharf.

Why do we tell this tale, and how did it originate?

The signal story was fabricated ninety-two years later to promote the image of an all-powerful Sam Adams, in firm control of the Boston crowd. George Bancroft, writing in 1854, condensed the timeline of the source information, leaving out the critical gap between Adams’s proclamation and the war whoops: “Samuel Adams rose and gave the word: ‘This meeting can do nothing more to save the country.’ On the instant, a cry was heard at the porch; the war-whoop resounded; a body of men, forty or fifty in number, disguised and clad in blankets as Indians, each holding a hatchet, passed by the door; and encouraged by Samuel Adams, Hancock, and others, and increased on the way to near two hundred, marched two by two to Griffin’s Wharf.”[4] The foreshortened narrative both heightened the drama and hinted at an element of causality: Tea Party participants were responding directly to Adams’s words, and he urged them on.

A few years later, in 1865, William V. Wells, Adams’s first biographer, took Bancroft’s narrative and made it part of a pre-conceived plot. Adams’s statement was “the signal for the Boston Tea Party,” he pronounced definitively. “Instantly a shout was heard at a door of the church from those who had been intently listening for the voice of Adams. The war whoop resounded. Forty or fifty men disguised as Indians, who must have been concealed near by, appeared and passed by the church entrance, and, encouraged by Adams, Hancock, and others, hurried along to Griffin’s, now Liverpool Wharf.”

This was the ultimate “Sam” Adams story – the people of Boston had been trained to follow a secret, coded message issued by their master – and Americans have been telling it ever since.[5]

There is a moral to this simple tale: historical accuracy demands documentation from primary sources. As a Revolutionary Era historian, I actually take this one step further: full documentation is downright patriotic. Here, in a five-minute TEDx Talk geared to youth, I present my case.

[1] Louis Birnbaum, Red Dawn at Lexington (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1986), 29. See also A. J. Langguth, Patriots: The Men Who Started the American Revolution (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1988), 179.

[2] L. F. S. Upton, ed., “Proceeding of Ye Body Respecting the Tea,” William and Mary Quarterly, Third Series, 22 [1965]: 297–298. This manuscript from the Sewall papers in Ottawa is accepted by scholars as the most detailed contemporaneous rendition of the meeting at Old South.

[3] Francis S. Drake, ed., Tea Leaves: Being a Collection of Letters and Documents relating to the Subject of Tea to the American Colonies in the year 1773 [Boston: A. O. Crane, 1884], LXX.

[4] Bancroft, History of the United States, 4: 280.

[5] William V. Wells, The Life and Public Services of Samuel Adams (Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press, 1969; first published, 1865–1888), 2: iv, and 2: 122. The idea of a “signal” was first suggested by William Gordon in 1788. Writing in the present tense to bring his readers closer to the action, a narrative fabrication implicated for many later mythologies, Gordon wrote that upon Rotch’s announcement “there is a great deal of disputing, when a person disguised like an Indian, gives the war-whoop in the front gallery, where there are few if any besides himself. Upon this signal it is moved and voted that the meeting be immediately dissolved. The people crowd out and run in numbers to Griffin’s wharf.” (The History of the Rise, Progress, and Establishment of the Independence, of the United State of America [Reprint edition: Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press, 1969], 1:341.) In this rendition, it was not Adams who gave the alleged “signal” but an unnamed person with a war-whoop. While Gordon’s timing, like Bancroft’s and Wells’s, is inconsistent with firsthand testimony, if there was some sort of “signal,” a war-whoop seems a more plausible candidate than Adams’s alleged coded message.

2 Comments

In the film business, a real fact is changed in the script because “IJMD” … “It’s just more dramatic”. If there was ever a classic founding era myth you’ve busted, Ray, it’s this one. The Disney film “Johnny Tremain” (still shown in classrooms to this day) has the dramatic orchestra come in IMMEDIATELY after Samuel Adams says those mythic words from the pulpit. The “Indians” immediately head down to the wharf, singing the film’s title song “The Sons of Liberty”. Real life is messier … but real! Thanks again, Ray!

Thanks, Ray (and John L. Smith)- I saw “Johnny Tremain” as a kid – and never forgot that terrific scene…although, even as a kid I wasn’t buying it. Now, I’m an old skeptic…then, I was a young skeptic. Thanks for setting me straight after all these years.