In 1781, British forces operating in Canada set their eyes on kidnapping prominent Americans in Vermont and upstate New York. These patriot leaders had stirred up opposition to efforts to draw Vermont into British Canada. At the time, General Frederick Haldimand, the Governor of the Province of Quebec (which at that time included what is now Ontario), was engaged in negotiations with Ethan Allen and other political representatives of the Republic of Vermont, which had declared its independence from the state of New York in 1777. The British tended to view events as controlled by great men; they hoped that by removing these patriot leaders their followers would become demoralized and the movement in Vermont to become a new province of British-held Canada would be energized.

In the spring, Captain Azariah Pritchard of the King’s Rangers, a Loyalist unit led by renowned frontier fighter Major Robert Rogers, took advantage of an opportunity to kidnap militia officer Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Johnson of Newbury, Vermont. A miller by trade, Pritchard had lived in Derby, Connecticut, before the war. He had subsequently fled with his family to Quebec and become a secret agent for the British army, carrying out numerous missions in Connecticut and Vermont.[1] On the night of March 8, 1781, Pritchard and ten of his men surprised and abducted Johnson from Peacham, Vermont, and then marched him through the northern woods to the British fort at St. Johns (now called Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu), Canada, a major British outpost just south of Montreal.[2]

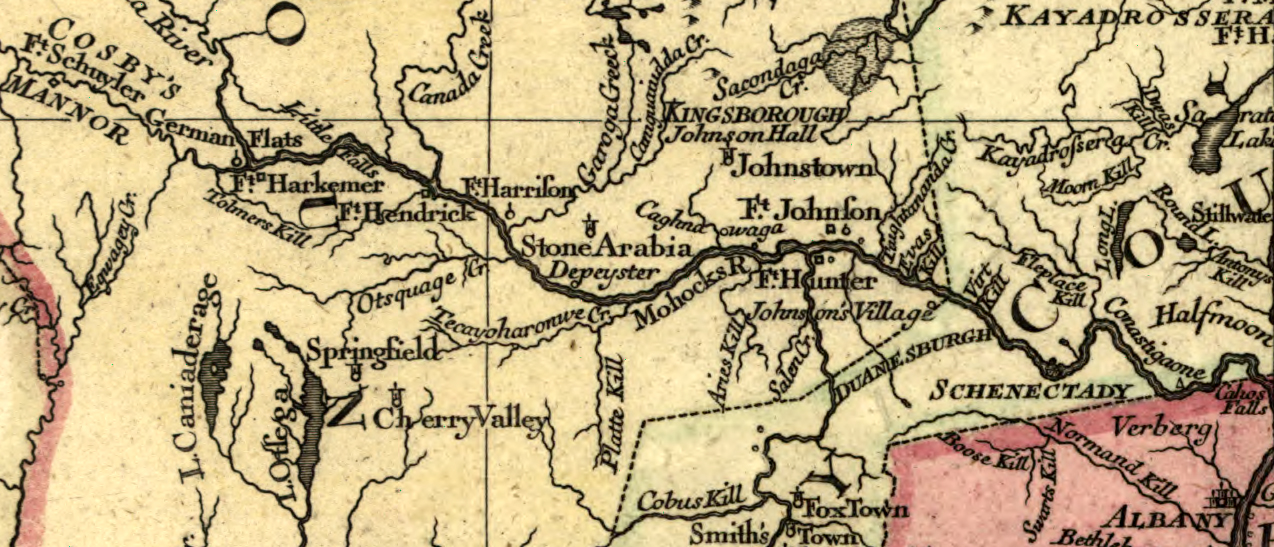

Pritchard’s success spurred additional British kidnapping attempts in the Albany, New York area. The targets included Philip Schuyler, then a retired major general of the Continental army. In early May Sir John Johnson, a prominent Loyalist leader who after the commencement of the war had fled from his vast estate in upstate New York, proposed to Governor Haldimand the abduction of Schuyler from his Albany home.[3] The Swiss-born Haldimand deferred. In early July, however, Dr. George Smyth, a Loyalist doctor who had fled to Canada from Albany and had since regularly assisted the British in upstate New York operations, suggested to Haldimand the kidnapping of a number of patriots—those who were “the most obnoxious to the friends of government in the neighborhood of Albany.” This time Haldimand agreed. He immediately informed the head of British secret service operations in Canada, Captain Justus Sherwood, a Loyalist from Vermont, that he wanted the operations “to be carried into execution with all possible dispatch.”[4]

By mid-July, Sherwood and his deputy, Smyth, had eight detachments ready to be sent from their base of operations, an island in Lake Champlain. Each party assigned to travel into New York State would consist of from four to six Loyalists and, at Haldimand’s insistence, two British regulars—it appears that Haldimand did not trust Loyalists alone to complete the tasks. Sherwood and Smyth chose the Loyalists, and Lieutenant Colonel Barry St. Leger of the British army selected the regulars. Each of the parties was to be close its quarry by July 31, but none was to strike before then, allowing the parties with farther to travel to reach their destinations without alarms.[5]

The first, and most important, task of seizing General Schuyler fell to Captain John Walden Meyers. In July 1777 Meyers had given up his 200-acre Albany farm and headed to join Burgoyne’s army descending from Canada. He had subsequently acquired a reputation as an effective frontier raider. One story told of his trekking through the New York woods to join Burgoyne’s force. When his faithful dog became fatigued, Meyers carried the pet, which drew comment from his brother-in-law, who had accompanied him. “We may have to eat him yet,” Meyers responded in his thick, German accent.[6] In Canada, in June of 1781, Meyers received command of his own unit, dubbed Meyers’s Independent Company.[7] But it was understrength, at times with only about twenty men.[8] Meyers’s party sent to abduct Schuyler consisted of only about twelve men, including two British regulars from the 34th Regiment, dressed in long smocks and buckskin breeches.[9]

While he had resigned his post as major general in the Continental army, Schuyler remained a prominent patriot in political circles and a military organizer in New York. Furthermore, he was, along with George Washington, one of the wealthiest and most socially prominent men in America. He was the head of one of a handful of landed patrician families—including the Livingstons, van Cortlands and van Rensselaers—that dominated the Hudson River Valley. Each owned huge manorial estates worked by hundreds of white tenant farmers, a rarity in the United States. Accustomed to the meek deference of his tenants and others in his socially stratified world, Schuyler was now the target of a kidnapping operation to be undertaken by a small band of common men.

Fortunately for the general, the Great Kidnap Plot of 1781 quickly went awry. First, Joseph Bettys, who led one of the raiding parties to nab a patriot leader at Ballstown, New York, took a detour and persuaded a young woman to run off with him. The woman’s father complained to the Albany County Commissioners for Detecting Conspiracies, which sent out search parties to find and arrest Bettys. The plot was revealed in greater detail when the commander of another of the raiding parties, Matthew Howard, targeting a patriot leader at Hoosick Falls, New York, was captured with written British secret service instructions in his possession.[10] After hearing more reports from local inhabitants, on July 29, the Albany County Commissioners for Detecting and Defeating Conspiracies warned Schuyler that Captain Meyers and a small party were lurking in the woods near Albany, intending to capture or assassinate him. But despite receiving this and other warnings, the American general did not reinforce his guard of four soldiers from the Second New York Regiment. “My gates and outward doors in the rear of my house were closed and secured at sunset, and four white men and two blacks were armed,” Schuyler wrote later to the governor of New York, former brigadier general George Clinton.[11]

Schuyler remained at his commodious home, which he called The Pastures, now known as the Schuyler Mansion. Located in an exposed position two miles south of the then Albany town limits, it contained in addition to the general his wife, Catherine, and three adult female relatives (two of them pregnant), perhaps six children, at least six white and black male and female servants, and just four guards.[12] After hiding his party in a friend’s barn near The Pastures from July 29 until the search parties had exhausted themselves more than a week later, Myers was finally ready to act. At about 9:00 p.m. on August 7, Meyers and his raiders attempted to forcibly enter the back door of Schuyler’s home, as the general and his family dined on the main floor near the open front door overlooking the Hudson River.

In a letter to Washington penned the next day Schuyler explained that Meyers and about twenty men had forced open the backyard gate. Some of them then broke into the house’s back door, where four servants “flew to their arms” to offer resistance. A patriot newspaper added the following details: “two white men [soldiers] and a Negro [an armed servant], who discharged their muskets, and made several thrusts with the bayonet at them, whereby it is supposed some were wounded, as much blood was left on the place. This resistance delayed their proceedings, until they had secured the two white men, and wounded the Negro, who notwithstanding made his escape.”[13] With the attackers momentarily delayed, Schuyler explained to Washington that he took the opportunity to “retire out” of the hall on the main floor to an upstairs bedroom where he kept his weapons. Some of the attackers had surrounded the house while others continued to try to force their way indoors. Schuyler fired his pistols from a window, even as Meyers’s men “got into the salon [upper hallway] to attempt as I suppose the room I was in.” Alarmed by Schuyler’s firing, the attackers “retreated with precipitation as soon as they heard me call ‘come on my lads, surround the house, the villains are in it.’ This I did to make them believe that succor was at hand and it had the desired effects.”[14] The raiders withdrew, carrying off two of Schuyler’s defenders and some of his silverware. Local militia arrived too late to engage them.

After Meyers’s departure, an excited but safe Schuyler quickly scribbled a note to Assistant Quartermaster General Henry Glen of Schenectady, writing that “one of my people bravely defended the door which gave time for me to gain my room, where I remained without their attempting me. By firing I alarmed the town, which turned out with alacrity and expedition. The villains carried off one of my men, wounded another, and took some of my [silver] plate.”[15] The former general requested that Glen send out friendly Oneida and Tuscarora Native Americans to track the raiders through the forests along the Mohawk River.[16] But Meyers split his group into small parties and each of them evaded all searchers. Governor Clinton, who in a few days would be warned by Washington of a separate plot to kidnap him (the third one of the war targeting him), increased the guard at Schuyler’s residence.[17]

Captain Meyers returned safely to St. Johns on the morning of August 17 and provided his superior officer, Lieutenant Colonel Barry St. Leger, with a different version of the action. Meyers explained that his party had been “too small to effect his purpose, Schuyler’s house being too large to be invested by a few men, by which means he [Schuyler] escaped by a back window.”[18] Here, Meyers believed Schuyler’s resourceful guards, who minutes after the attack commenced had shouted that the general had jumped out of the window and was long gone[19]—they had fooled Meyers. St. Leger subsequently wrote: “The attack and defense of the house was bloody and obstinate, on both sides. When the doors were forced, the servants fought till they were all wounded or disarmed. The uproar of Mrs. Schuyler and the cries of the children obliged them to retire with their two prisoners being the only persons that could be moved on account of their wounds. Two men of the 34th Regiment were slightly wounded.”[20] It appears that the uproar caused by the servants, women, and children in Schuyler’s house helped as much as the general’s gunfire to drive Meyers away.

According to Canadian historian Mary Beackock Fryer, a local man Meyers had recruited for the mission was killed in the attack.[21] Kevin Richard-Morrow, who has studied the attempt to abduct Schuyler, wrote that “The two captured Schuyler guards, John Tubbs and a private Lockey of Van Schaik’s Continentals, returned to the Albany area after the war.”[22]

If Meyers’s party was only twelve men, and not twenty as Schuyler thought, it probably was too small to accomplish the mission once the element of surprise had been removed after Schuyler had been forewarned. Meyers ordered one or more men to watch outside in the event Schuyler tried to escape using another door or window, thus making the task of overpowering Schuyler’s six defenders more difficult. The patriot newspaper report indicated that Meyers had twelve or thirteen attackers, thus giving credence to Meyers’s account.[23]

In fact, none of the eight raids authorized by General Haldimand and launched by Sherwood and Smyth paid off. In my recent book, Kidnapping the Enemy: The Captures of Major Generals Charles Lee and Richard Prescott (Westholme, 2013), I focused on two of the outstanding special operations of the Revolutionary War: the stunning capture of Major General Charles Lee by a party of British dragoons led by Lieutenant Colonel William Harcourt, and the capture of Major General Richard Prescott by Rhode Island patriot Lieutenant Colonel William Barton. What made Barton’s and Harcourt’s missions unusual were that they succeeded. Few other special operations launched to kidnap generals or high-ranking government officials did, as demonstrated in part by two recent articles in this Journal: “Raid Across the Ice: the British Operation to Capture Washington” (Dec. 17, 2013), Benjamin Huggins and my [“Washington Attempts to Capture a Future King of England”] (Jan. __, 2014). What made the attempt on Schuyler unusual was that it came within a hair’s breadth of succeeding.

[FEATURED IMAGE AT TOP: Major General Philip Schuyler. Source: Schuyler Mansion State Historic Site, Albany]

[1] “Pritchard, Aaron,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, VI (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1987), 616.

[2] Abby Maria Hemenway (ed.), Vermont Historical Gazetteer . . . ., II (Claremont, NH: Claremont Manufacturing Company, 1877), 928; Thomas Johnson Journal Entry, March 8, 1781, in Dictionary of Canadian Biography. British officers treated Johnson kindly in an effort to turn him to their cause as part of the British effort to influence Vermonters to join Canada. Refused in his requests to be exchanged formally, and as a condition for his release in October of 1781, Johnson finally agreed to provide the British with intelligence, to assist Loyalist scouts, and to return to Montreal if requested. Still a firm patriot, he later explained his predicament to Washington, stating that he had intended to serve as a double-agent for the patriot cause. Washington understood and exonerated Johnson. See T. Johnson to G. Washington, May 30, 1782, in Hemenway, Vermont Historical Gazetteer, 929-30; T. Johnson to G. Washington, July 20, 1782, in Hemenway, Vermont Historical Gazetteer, 930; M. Weare to G. Washington, Nov. 25, 1782, in Hemenway, Vermont Historical Gazetteer, 930; N. Peabody to G. Washington, Nov. 27, 1782, in Hemenway, Vermont Historical Gazetteer, 930-31; see also G. Washington to T. Johnson, June 14, 1782, in Hemenway, Vermont Historical Gazetteer, 930 and John C. Fitzpatrick (ed.), The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources, 1745-1799, XXIV (Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, 1938), 341-42; G. Washington to J. Bayley, June 13, 1782, in Fitzpatrick, The Writings of George Washington, 337-39.

[3] Don R. Gerlach, Proud Patriot, Philip Schuyler and the War of Independence (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1987), 458.

[4] R. Mathews to J. Sherwood, July 4, 1781, quoted in Robert Maguire, “The British Secret Service and the Attempt to Kidnap General Jacob Bayley of Newbury, Vermont, 1782,” Vermont History 44:146 (Summer 1976).

[5] Fryer, Mary Beacock, King’s Men: the Soldier Founders of Ontario (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 1980), 284-85.

[7] A recent thorough study of the backgrounds of Loyalist officers states that Meyers was appointed captain in the 2nd Battalion of the King’s Rangers (Robert Rogers’s outfit) on November 24, 1780 and served as a captain of his own unit, Meyers’s Independent Company, in June of 1781. Walter T. Dornfest, Military Loyalists of the American Revolution: Officers and Regiments, 1775-1783 (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Company, 2011), 244. See also Loyalist Rev. War Claim, summarized in Peter W. Coldham (ed.), American Migrations, 1765-1799, The Lives, Times and Families of Colonel Americans Who Remained Loyal . . . . (Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Publishing Co., 2000), 307 (Myers of Albany County had a 200-acre farm, with house and cattle).

[9] Fryer, Loyalist Spy, The Experiences of Captain John Walton Meyers during the American Revolution (Brockville, Ontario: Besancourt Publishers, 1974), 124 and 128.

[11] P. Schuyler to G. Clinton, Aug. 9, 1781, in Hugh Hastings (ed.), Public Papers of George Clinton, First Governor of New York, 1777-1795—1801-1804, VII (Albany, NY: Oliver A. Quayle, 1904), 184-86.

[14] P. Schuyler to G. Washington, Aug. 8, 1781, quoted in Gerlach, Proud Patriot, 459-60. Schuyler biographer Don Gerlach further wrote: “John Van Zandt (1767-1858), then a boy of about fourteen, later remembered hearing the signal gun from the Schuyler house when the raiders surprised the general. Joel Munsell, The Annals of Albany, 10 vols. (Albany, 1850-59) 10:413.” Gerlach, Proud Patriot, 584, n 46. The Schuyler Mansion in Albany is located at 32 Catherine Street.

[17] P. Schuyler to G. Clinton, Aug. 9, 1781, in Hastings (ed.), George Clinton Papers 7:185 (increased guard); G. Washington to G. Clinton, Aug. 10, 1781, in Fitzpatrick (ed.), Washington Writings 20:491 (Washington provides detailed threat of kidnapping plot against Clinton); G. Clinton to P. Schuyler, Aug. 14, 1781, in Hastings (ed.), George Clinton Papers 7:193-94 (Clinton informed Schuyler that this was the third plot to kidnap him).

5 Comments

With the move underway to besiege Yorktown, I suspect that even if Meyer had succeeded and made his way back to Canada with Schuyler(which by no means was a certainty), the victory at Yorktown might have put an end to Schuyler’s capture. Do you know what reaction Schuyler’s new son-in-law, Alexander Hamilton, may have had to this failed attack? Thanks for a great article that nicely captures the action of the event in such a short space.

Steven: Thanks for the compliment. I do not know of Alexander Hamilton’s reaction, but it is a good question and I will look into it. His papers tend to a bit sparse during the Revolutionary War years, but I will definitely check. Recall that my last article was about Washington’s attempt to capture Prince William Henry in New York City in March of 1782, months after Yorktown!

Likewise, an enjoyable article. Had both Meyers and GW been successful, I would love to be in on the prisoner negotiation.

Ah, yes … Joseph Bettys in charge of a Brit raiding party. In October of 1776, he had served as mate on board the gunboat “Philadelphia” that sank during the battle of Valcour Island. As the boat sank, he and the rest of the crew had been taken about the galley “Washington.” Two days later, that ship struck her colors to the British fleet and Bettys had his introduction to the British army.

Christian: Very nice article. In my research on the 2nd New York of 1775, I found out some very interesting details on the raid: Besides Schuyler himself, there were six men at the mansion: three of his personal guard (drafted from the 1st New York), a courier, and two unidentified black men. Pvt. John Cockley (former 2nd New Yorker from 1775), who was wounded, and John Tubbs, the unfortunate courior who just happened to be there, were taken prisoner. Pvt. Jon Ward was wounded, and presumably bad enough to be left behind. A third guard and one of black men were in another room and avoided capture. I am not sure what happened to the 2nd black man.

Cockley and Tubbs (sorry, I had to do that) were returned in 1782. I know Cockley returned by ship from Quebec and landed in Boston in November. (I need to check on Tubbs, just to close the story.)

Upon their return, Cockley, Tubbs, and Ward, were rewarded by the General, for their gallant efforts in this action, with 275 acres of land from the Saratoga Patent. The Land was deeded to the men as tenants in common, and they drew lots for their respective portions.