British Lt. Gen. Alexander Leslie, 50, was burned out, ill, missed his daughter, and wanted to go home.

He had arrived in South Carolina in late 1781 to command the Southern colonies. Leslie needed to ensure the security of the few enclaves the British still controlled. He had to feed not just his own army, but thousands of loyalist refugees and escaped slaves, many of whom had been promised freedom for fighting. In addition to the usual army diseases—dysentery and typhus—malaria thrived in the mosquito-ridden climate.

His original orders, from Gen. Henry Clinton, the commander in chief, were to hold Charlestown (renamed Charleston after the war) at all costs. He directed Leslie to “preserve as many of our remaining posts in that province as he can, consistent with the safety of Charlestown.”[1] New orders—secret ones—arrived in May 1782 from Clinton’s successor, Gen. Guy Carleton: Evacuate the South.

But Leslie was exhausted after serving 14 years in America, 10 of them consecutive, seven of them at war. He first begged Clinton, then Carleton, to be relieved. His health, he told them, was “much impaired from having served the whole war. … From sickness and accidents, by falls, dislocations, etc., my health is unfit to stand the summer.” Moreover, the stress from dealing with the problems of the loyalist refugees was “so much beyond my abilities to arrange that I declare myself unequal to the task.” His 82-year-old mother was dying and his only daughter refused to marry until he returned to Britain.[2] “My country has got her full share out of me,” Leslie wrote.[3]

Neither Clinton nor Carleton agreed. Leslie was experienced, reliable, and trusted. The son of a Scottish peer and ancestor of a namesake 17th century general, Leslie was born in 1731, joined the army by his early 20s, and was steadily promoted. When he was 29, the then–Maj. Leslie married. His wife died a year later after giving birth to a daughter.[4]

He arrived in Boston, Mass., in 1768 as a regimental commander and lieutenant colonel. He was, a fellow officer said, “a genteel little man, lives well, and drinks good claret.”[5] At one point, Leslie was posted to Halifax, but by the summer of 1772, with tensions rising in Massachusetts, he returned to Boston.[6]

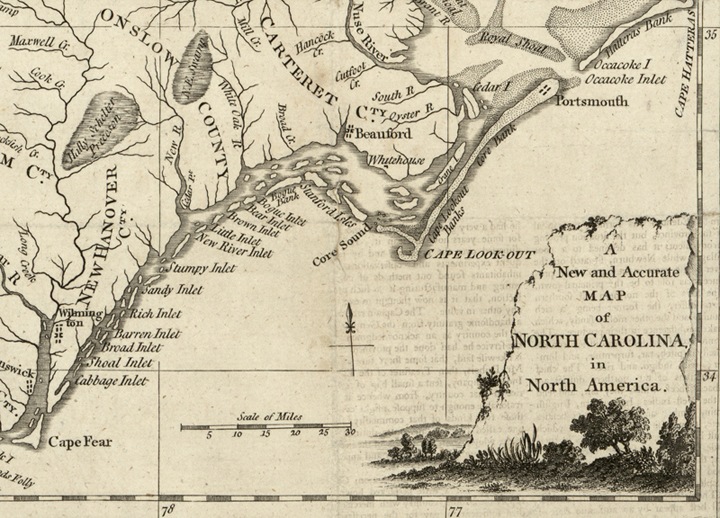

In late 1774, anti-British rebels secured some ancient cannon, began converting ships’ cannon into field pieces, and smuggled in new artillery.[7] Col. Leslie, commanding about 250 men, was ordered to seize or spike a cache of cannon from a blacksmith’s shop in Salem, a wealthy port of 5,000 people, 25 miles north of Boston. The blacksmith’s shop was located just across the North River from Salem.

On Sunday morning, Feb. 25, 1775, Leslie and his men arrived in the neighboring town of Marblehead and marched the five miles to Salem. A growing, abusive crowd of residents and rebel militia greeted the British at the North River. There, they had raised the river’s drawbridge, preventing any crossing. It was an angry standoff settled only in the late afternoon. The rebels lowered the drawbridge, and Leslie fulfilled his orders by marching across the bridge—and then immediately marched back. By then, the rebels had moved the cannon, and everyone knew it.

The war would begin 52 days later at Lexington and Concord. Leslie’s career paralleled the events of the war. He helped plan the defense of Boston and fought in a skirmish.[8] At the battles for New York in 1776, the now-promoted Brig. Gen. Leslie led troops at the Battle of Long Island, the landing at Kip’s Bay, the defense of Harlem Heights, and the Battle of White Plains.[9] In January 1777, Leslie’s men failed to detect Washington and the rebel army passing nearby on the way to a successful attack on Princeton, N.J.[10] For two years, Leslie commanded the troops in strategically important Staten Island and was rewarded in 1779 with another promotion, to major general.[11]

He participated in the capture of Savannah and Charlestown in late 1779 and spring 1780, then returned to New York.[12] Later that year, he commanded 2,500 men raiding rebel supply lines in Virginia, and established a base in Portsmouth, Va.[13] In January 1781, Leslie brought reinforcements to the Carolinas, but delayed by bad weather, he was too late to support troops at the Battle of Cowpens.[14] At the Battle of Cowans Ford on Feb. 1, Leslie nearly drowned. In March, at Guilford Courthouse, he commanded the British right wing. As the spring came, Leslie’s health deteriorated, and he returned to New York to recuperate until ordered to take the southern command.

His time in Charlestown was difficult. A vicious partisan civil war—raids and looting with a brutality that appalled both Leslie and his rebel counterpart—seemed unstoppable. The British outposts faced frequent skirmishes, so many that Leslie authorized troop withdrawals from Wilmington, N.C., and Savannah, and shrunk his defense perimeter in South Carolina to strengthen Charlestown. When he later announced the city’s evacuation, he had to address loyalist fears as well as deal with thousands of British- and loyalist-owned slaves and escaped slaves to whom freedom had been promised. By May 1782, he was responsible for feeding nearly 16,000 men, women, and children.[15] “Their misery and helpless situation justifies our attention to them,” he wrote Carleton.[16]

When the rebel legislature ordered the confiscation of loyalist property, Leslie retaliated by confiscating rebel property—that is, slaves—from plantations in the countryside outside Charlestown. He could, he told the rebels, “no longer remain the quiet spectator of their [loyalist] distresses.”[17]

The rebel commander, Gen. Nathanael Greene, infuriated and frustrated Leslie. After Parliament voted to end the offensive actions in early 1782, Leslie tried to negotiate a ceasefire—“a duty I owed to the rights of humanity…”[18] Greene refused. To him, Leslie’s ceasefire proposal was a scheme that would allow Britain to focus its efforts against the French. After a French defeat, the British would turn their attention again to the Americans.[19] Washington concurred. “Sir Guy Carleton is using every art to soothe and lull our people into a state of security.”[20]

Leslie renewed foraging raids in the countryside to feed his people. As for prisoner exchanges, “I can’t get General Greene to make any exchange of prisoners nor do anything. He is a downright lawyer.”[21] What Leslie and Greene shared was a desire for a peaceful evacuation, one in which British troops, loyalists, and allied blacks went unharassed by rebel fire, and Charlestown itself wasn’t left looted or burned. “It is said that General Leslie exerts himself all he can to preserve order, but he is so badly supported that his orders are but indifferently executed,” Greene reported.[22] They reached an agreement on Dec. 13, and the next day, Leslie, his troops, and remaining refugees evacuated Charlestown and the South. Most refugees went to Nova Scotia, but others settled in Florida, Jamaica, New York, and Britain itself.

Leslie returned to Scotland in 1783. He became second-in-command of the standing British army based in the country, where many remained unhappy at its 1707 union with England. He celebrated the wedding of his only child, Mary-Anne, in 1787.[23] Virtually all noncontemporary accounts of Leslie’s death say he either died from wounds received putting down a Glasgow riot on Dec. 17, 1794, or from an illness that was somehow related to the riot.

But that’s incorrect, a myth created by an 1842 book and then distorted or poorly summarized by ensuing historians, the latest of which is a 2013 scholarly book about Leslie’s Salem raid of 1775.[24] The facts were related in an eyewitness account published in the Dec. 22, 1794 Times of London: Earlier in December, there had been a mutiny, and Leslie had ordered five arrested ringleaders to be transported from Glasgow to Edinburgh. One of the ringleaders was a grenadier, and fellow grenadiers freed him without resistance from the guards. A mob attacked two officers that were part of the guard: an adjutant and a Major Leslie—not the general:

“They were assailed with stones by the mob and were obliged to fly for shelter in the first house they met with. Major Leslie was knocked down with a stone, but received no material injury except a slight cut over the temple.”[25]

The Times account differentiates between Maj. Leslie and Gen. Leslie (without identifying if the two were related). But this distinction has been ignored by historians. The confusion comes not just because of the same last names of the major and the general, but because Gen. Leslie died at his home near Edinburgh on Dec. 27, just 10 days after the riot.

His death came “after a few days illness,” according to an obituary. But the obituary writer, not knowing how diseases are transmitted, assumed the Leslie’s illness was “caught at Glasgow in the service of quelling the late riots there.”[26] Leslie was 63.

[1] Clinton to Lord Germain, Oct. 29, 1781, K.G. Davies, ed. Documents of the American Revolution (Colonial Office Series), vol. 20, (Dublin: Irish University Press, 1979), 252.

[2] Leslie to Clinton, March 27, 1782, Historical Manuscripts Commission, Report on American Manuscripts in the Royal Institution of Great Britain, vol. II (Dublin: John Falconer, 1906) 434 (accessed in Internet Archive).

[3] Leslie to Carleton, June 27, 1782, Historical Manuscripts Commission, Report on American Manuscripts in the Royal Institution of Great Britain, vol. II, 543-544.

[4] For Leslie’s early history, see Kenneth Rutherford Davis, The Rutherfords in Britain: a History and Guide, (Gloucester, UK: Alan Sutton Publishing, 1987), 42-45, excerpt published in genealogy.com, “Sir John Rutherfurd of that Ilk and Edgerston,” http://genforum.genealogy.com/rutherford/messages/6047.html (accessed 2-8-12); John Debrett, Debrett’s Peerage of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, vol. 2. (London: G. Woodfall, 1828), 526, Google Books; Richard L. Blanco, ed., The American Revolution, 1775-1783, An Encyclopedia (New York: Gardland Publishing, Inc., 1993), 919; H.G. Purdon, Memoirs of the Services of the 64th Regiment (Second Staffordshire) 1758 to 1881, (London: W.H. Allen & Co., [1882]), Google Books; H.G. Purdon, An Historical Sketch of the 64th Regiment by Major H.G. Purdon, http://web.archive.org/web/20010911013815/http://www.cvco.org/sigs/reg64/64th_sketch.html (accessed March 7, 2010); Marg Baskin, “Alexander Leslie,” Oatmeal for the Foxhounds: Banastre Tarlton and the British Legion, http://home.golden.net/~marg/bansite/btfriends.html (accessed 9-13-09); and Essex Institute, “The Affair at the North Bridge, Salem, February 26, 1775.” Historical Collections of the Essex Institute, vol. 38, no. 4, October 1902, 325, Google Books.

[5] John Peebles and Ira D. Gruber, John Peebles’ American War: A Diary of a Scottish Grenadier, 1776-1782, (Stroud, U.K.: Sutton Publishing, 1998), 179.

[6] John Richard Alden, General Gage in America: Being Principally a History of His Role in the American revolution, (Baton Rouge, La.: Louisiana State University Press, 1948), 181, 190.

[7] Much of the following account is from Charles M. Endicott, Account of Leslie’s Retreat at the North Bridge, on Sunday, Feb’y 26, 1775, (Salem, Mass.: Wm. Ives and Geo. W. Pease Printers, 1856) 13-31, Google Books; David Hacket Fischer, Paul Revere’s Ride, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 58-63; and Robert S. Rantoul, “Some Claims of Salem on the Notice of the Country,” Historical Collections of the Essex Institute, vol. XXXII, 1896, 3-13, Google Books.

[8] Norman Desmaris, The Guide to the American Revolutionary War in Canada and New England, (Ithaca, New York: Busca, Inc., 2009), 124; and Purdon, An Historical Sketch of the 64th Regiment by Major H.G. Purdon.

[9] Theodore P. Savas and J. David Dameron, A Guide to the Battles of the American Revolution, (New York: Savas Beatie, 2010) 137-138, Adobe digital edition; and Blanco, The American Revolution, 1775-1783, An Encyclopedia, v. 1, 919.

[10] Harold E. Selesky and Mark Mayo Boatner, Encyclopedia of the American Revolution, second edition: Library of Military History, (Detroit: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2006), 620.

[11] Phillip Papas, That Ever Loyal Island: Staten Island and the American Revolution, (New York: New York University Press, 2007), 101; and Historical Manuscripts Commission, Report on American Manuscripts in the Royal Institution of Great Britain, vol. I (London: Mackie & Co., 1904), 410, Internet Archive.

[12] Historical Manuscripts Commission, Report on American Manuscripts in the Royal Institution of Great Britain, vol. II, 76; and Baskin, “Alexander Leslie.”

[13] Selesky, Encyclopedia of the American Revolution, 620; and Blanco, The American Revolution, 1775-1783, An Encyclopedia, vol. 1, 920.

[15] Estimates by former British commissary James Chastillier in Nathanael Greene, The Papers of General Nathanael Greene, Dennis M. Conrad, ed., vol. XI, 7 April—30 September 1782, (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2000), 117.

[16] Leslie to Clinton, Jan. 29, 1782, Historical Manuscripts Commission, Report on American Manuscripts in the Royal Institution of Great Britain, vol. II, 388.

[17] Leslie to Francis Marion, April 4, 1782, Robert Wilson Gibbes, Documentary History of the American Revolution: 1781-1782 (D. Appleton & Co.: New York, 1857), 153, Internet Archive.

[19] Greene to President John Hanson, May 21, 1782, Greene, The Papers of General Nathanael Greene, vol. XI, 227-228.

[21] Leslie to Clinton, Dec. 27, 1781, in Davies, Documents of the American Revolution, vol. 20, 288.

[22] Greene to Anthony Wayne in Nathanael Greene, The Papers of General Nathanael Greene, Dennis M. Conrad, ed, vol. XII, 1 October 1782—21 May 1783, (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2002), 281.

[24] The original account was in John Kay, A Series of Original Portraits and Caricature Etchings, vol. II, part I, (Edinburgh: Hugh Paton, 1842) Google Books. It’s been repeated and distorted in many other accounts including Purdon, An Historical Sketch of the 64th Regiment by Major H.G. Purdon, and Peter Charles Hoffer’s Prelude to Revolution: The Salem Gunpowder Raid of 1775 (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013), 105.

4 Comments

Leslie writes, “I can’t get General Greene to make any exchange of prisoners nor do anything. He is a downright lawyer.” Hey — like being a lawyer is a bad thing?

Gave you a credit on

What’s New on the Online Library of the American Revolution.

A worthy subject to explore. I believe you may have overstated the case in your comment linking Leslie’s apppointment in “the standing British army based in” Scotland and your assertion that “many remained unhappy at its 1707 union with England.” `

Although in the 1790s there was social unrest in certain parts of the country, partly to do with landlord clearance of Highland communities in the north, the military presence in Scotland was not as an army of occupation to enforce the 1707 Union, which your reference, perhaps unintentionally, implies. There was also a degree of urban radicalism associated with the French Revolution, but this was countered by a strong Loyalist sentiment. The Jacobite movement, moreover, was a dead letter.

There were also several mutinies in Scottish Fencible regiments in the mid-1790s. As in the 1770s, this was essentially over perceived contravention of their terms of service from the particular point of view of Highland soldiery. It was partly a contractual issue and partly to do with evolving class distinctions in Highlander society and the unscrupulous exploitation of paternalistic class relations in rural districts.

Arthur: Thanks for your comment about the unrest in Scotland. My knowledge of Scottish history is a mile wide and an inch deep, so I defer to your expertise.

In my book, “After Yorktown,” I do try to counter US-centric views of the Revolution that we find in most history books written by Americans.

As a former journalist, I hate reading histories by US authors that talk about the “patriots” and “Americans,” as if loyalists and Native Americans weren’t equally patriotic and American. Yorktown, of course, was mostly a French victory; we don’t hear much about that in the US.

My website has a wonderful compendium of portraits, as well as cartoons—and an errata sheet for my book:

http://www.donglickstein.com