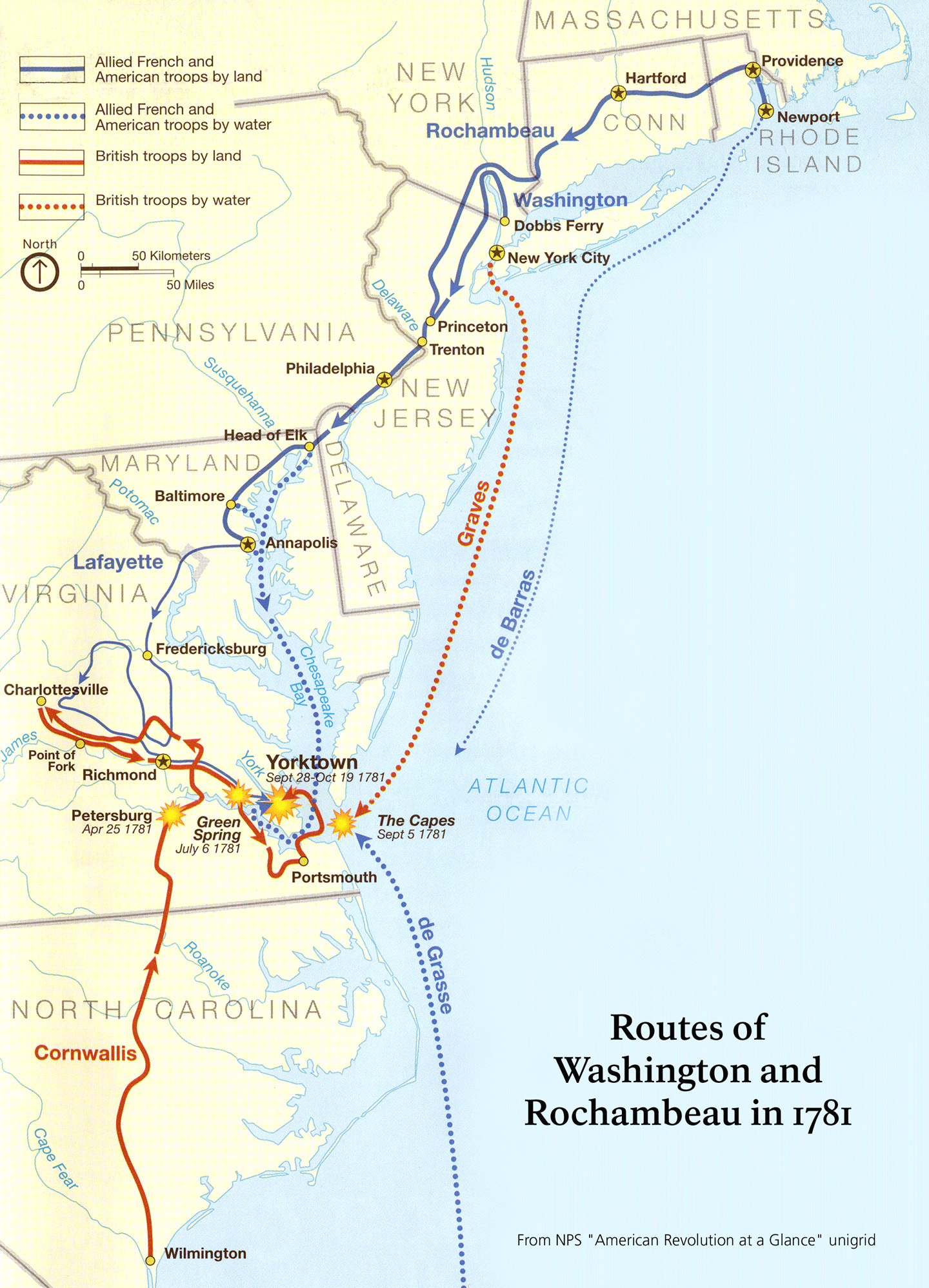

General Washington received the disappointing news on August 14, 1781. Comte De Grasse’s powerful French fleet of nearly thirty warships was not sailing for New York as Washington had long hoped, but was instead destined for the Chesapeake Bay. Washington’s plan for an allied attack on British held New York City depended heavily on the assistance of the French navy, so Count de Grasse’s decision to sail to Virginia instead of New York in August effectively derailed Washington’s strategy.

Fortunately, a few weeks earlier, General Washington – increasingly concerned and dismayed at the inability of the American states to send new recruits and adequate supplies to his army – had already shifted some of his attention southward, noting in his diary on August 1, 1781 that,

“Having little more than general assurances of getting the [requested support from the states and] with little appearance of their fulfillment, I could scarce see a ground upon [which] to continue my preparations against New York…and therefore I turned my views more seriously (than I had before done) to an operation to the Southward….”1

Count de Grasse’s decision to forsake New York actually simplified matters for General Washington as it left him with only one offensive option against the British. Washington immediately seized upon a new plan to cooperate with the French navy in the Chesapeake, noting in his diary on August 14 that,

“I was obliged…to give up all idea of attacking New York; & instead thereof to remove the French Troops & a detachment from the American Army to the Head of Elk to be transported to Virginia for the purpose of cooperating with [de Grasse] against the Troops in that State.”2

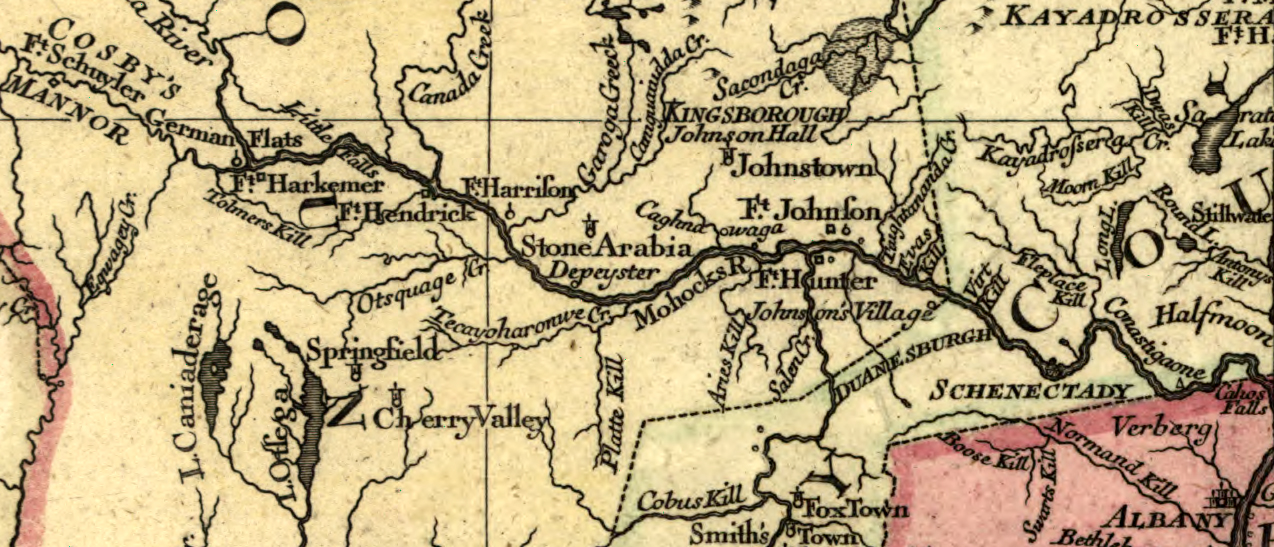

The British troops General Washington hoped to confront in Virginia (over 7,000 strong) were under the command of British general Lord Cornwallis. They had spent the first half of the summer disrupting Virginia’s efforts to supply the American army in South Carolina by raiding supply depots, chasing Governor Jefferson and the Virginia Assembly out of Richmond and Charlottesville, and pursuing the only significant American opposition force in Virginia, a 900 man detachment of American continentals (supported by a small number of Virginia militia) under General LaFayette of France. After a very active early summer in the field, General Cornwallis marched to Portsmouth with his army in July to await new instructions from his superior, General Henry Clinton in New York. By the start of August, Cornwallis was on the move again, entrenching his army along the York River at Yorktown and Gloucester Point in order to secure a strong base for the British navy.

General Washington was likely unaware that Cornwallis had moved to Yorktown when he made the fateful decision to march south with a portion of the American army (along with General Rochambeau’s entire French army in New York). Determined to expel the British from Virginia and assist General Nathanael Greene’s army in South Carolina (either by preventing Cornwallis from sending troops to South Carolina or by sending American reinforces to General Greene’s army himself), Washington instructed LaFayette on August 15th to do everything he could to prevent Cornwallis from marching south. Washington knew that LaFayette’s force alone could not stop Cornwallis, but he hoped LaFayette could at least delay the British if they did choose to march south, until Count de Grasse reached Virginia in late August with his powerful fleet and 3,500 French troops from the West Indies.3 Fortunately for Washington, General Cornwallis had no intention of leaving Yorktown and was unaware of the forces that were about to converge on him.

Directing his efforts against a 7,000 man British army 450 miles away – efforts that depended on the close cooperation of both the French army and navy – General Washington faced a daunting level of uncertainty that was heightened by communication challenges. Since it took approximately two weeks for messages from Virginia to reach him, and even more time for messages to reach Count de Grasse at sea, Washington often had to make decisions based on outdated information. Unsure whether Cornwallis would still be in Virginia when he and Rochambeau arrived, Washington pushed forward, asking Count de Grasse in a letter on August 17th to send all of his frigates and transport ships to the Elk River at the head of Chesapeake Bay in order to meet the armies and hasten their movement southward.4 Washington proceeded on faith that de Grasse would first secure control of the bay and second, send the requested ships up the bay to the Elk River.

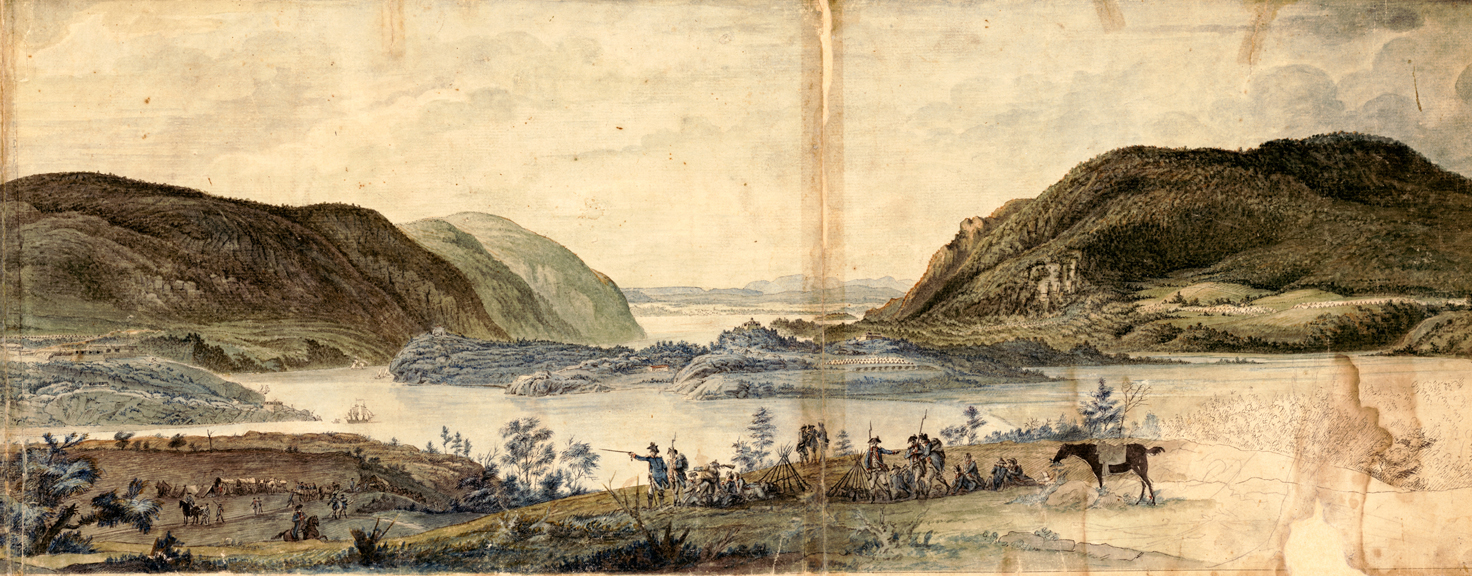

Leaving troops behind under General William Heath to defend West Point, Washington led a detachment of approximately 2,500 continentals across the Hudson River and southward through New Jersey.5 Three thousand French troops marched south as well.6 Fortunately for the allies, most of the heavy siege guns and ordinance were transported by a French naval squadron out of Rhode Island.

Efforts to deceive General Clinton into believing that New York was Washington’s target were initially successful; General Clinton reported in a letter to Lord George Germain in the British Ministry in early September that Washington had “crossed the [Hudson] River and by the position he took seemed to threaten Staten Island.”7 By September 7th, however, reports that Washington and Rochambeau had crossed the Delaware River convinced Clinton that Virginia was Washington’s real target.8 By then, a large portion of Washington’s and Rochambeau’s troops had boarded transport ships at Head of Elk and were sailing down the Chesapeake to join General LaFayette in Virginia.

Washington and Rochambeau led the rest of the army overland to Baltimore, where additional ships were procured. The cavalry, wagons, and cattle for the army, along with Washington and Rochambeau and their staffs, continued southward by land. General Washington ended a six year absence from his home at Mount Vernon on September 9th and Rochambeau caught up with him the next day. They stayed at Mount Vernon until September 12th and reached Williamsburg two days later where they re-joined their troops. Over the next two weeks, additional troops as well as cannon and other supplies poured into Williamsburg.

By the end of September, General Washington was ready to implement the next phase of his ambitious plan and he led the allied armies to Yorktown. From the ruins of Washington’s original plan against New York had emerged the campaign that ended the war, the Siege of Yorktown.

1 Donald Jackson, ed. “August 1, 1781,” The Diaries of George Washington (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1976-79) Vol. 3, 405.

3 John D. Grainger, The Battle of Yorktown, 1781: A Reassessment (Rochester, NY: Boydell Press, 2005), 46.

4 John C. Fitzpatrick, ed. “General Washington to Comte de Grasse, 17 August, 1781,” The Writings of George Washington, (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1931-1944) Vol. 23, 10-11.

5 Comments

Glad to see you contributing, Mike. I know you are loaded with interesting articles–info on the REAL rifle corps rather than the mythical and sharing some of your research on Arnold’s march to Quebec, for example.

While Mike’s version of Washington’s movement to Virginia has acceptance among many historians, there is also another view that for many months in 1780-81 he operated a deception plan against Clinton which resulted in isolating Cornwallis at Yorktown. The details of his operation are included in a forthcoming book, “Spies, Patriots and Traitors”, published by Georgetown University Press. Thus as the book’s author I cannot provide the text and citing here. But I did want to note that another point of view exists regarding Washington’s decision to head south.

Revisionist history and part of the Washington hagiography cabal.

The victory at Yorktown would not have been possible without the French. The French practically forced Washington to follow them South and attack Virginia. French money and credit paid for the campaign. French troops made up half the army there. French military engineers largely directed the siege. And most importantly the French navy repelled the British navy’s attempt to rescue the besieged British army.

Gave you a credit on

What’s New on the Online Library of the American Revolution.

When Clinton came to the realization that Washington was headed for Virginia, why didn’t Sir Henry send a large number of British or German troops into Westchester or New Jersey in order to pressure Washington into returning?