“…good weapons not wisely laid aside”

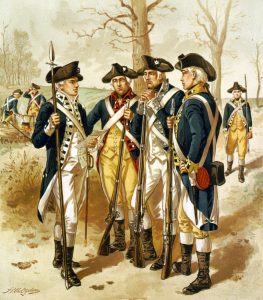

Wartime brings urgency to the quest for better weapons systems. That is as true today as it was during the American Revolution. However, the search for effective weapons does not always require seeking out the new or untried inventions. The needs may sometimes be met using old technology.

Indisputably, one of the great thinkers and inventors of any age was Benjamin Franklin. During the war he turned his mind to many things, one of which was finding an effective weapons system that the patriot forces could utilize that did not depend upon the importation of arms and ammunition from abroad. The extremely limited manufacturing capacity of the colonies could not hope to produce enough muskets and accouterments to supply the needs of a sizeable army.

Franklin believed he had found at least a partial solution to the problem. He wrote to Lieutenant General Charles Lee in February 1776, “that pikes could be introduced, and I would add bows and arrows; these were good weapons not wisely laid aside.” In this remarkable letter Franklin listed the attributes of bows and arrows:

- Because a Man may shoot as truly with a Bow as with a Common Musket.

- He can discharge 4 arrows in the time of charging and discharging one Bullet.

- His object is not taken from his view by the smoke of his own side.

- A Flight of Arrows seen coming upon them terrifies and disturbs the Enemy’s Attention to his Business.

- An Arrow Striking in any part of a Man, puts him hors de combat ‘till ‘tis extracted.

- Bows and Arrows are more easily provided every where than Muskets & Ammunition.

As incredible as it may seem to the 21st century reader Franklin quotes Virgil [circa 1470-1555, historian, employed by English King Henry VIII], in Latin, in the letter to General Lee. The letter continues:

Polydore Virgil speaking in one of our Battles against the French in Edward the 3rd Reign [reign 1327-1377] mentions the great confusion the Enemy were thrown into, sagittarum nube, from the English; and concludes, Est res profecto dictu mirabilis, ut tantus ac potens Exercitus a solis fere Anglicis Sagittariis victus fuerit; adeo Anglus est Sagittipotens, & Id genus armorum valet.

For those of us without the education of Franklin and Lee the Latin translation is: “Red (meaning blood) from the arrows, (from the English; and concludes) this thing is surely amazing, that so great and powerful an army to be shriveled by English archers; and those the English approach are so powerful, and their kind of armor was strong.”

Franklin continued, in English, to Lee:

If so much Execution was done by Arrows when Men wore some defensive Armour, how much more might be done now that it is out of use.[1]

In his February 1776 letter, Franklin commented that pikes, or spears, would also make useful weapons. Franklin had experience of long standing with pikes. On July 4, 1775, he had been requested by the Pennsylvania Committee of safety “to procure a model of a Pike.” Two days later Franklin, who was a member of the Committee, appeared with his model of a pike. The Committee ordered that one be made “to the pattern produced by Doctor Franklin.”[2]

Interest in pikes or spears was not confined to Franklin. For example, George Washington, the commander of the Continental Army at Cambridge, laying siege to Boston, ordered on July 14, 1775 that “the Commanding Officers in those parts of the Lines and Redoubts, where the Pikes are placed will order the Quarter Masters of Corps, to see the pikes greased twice a week, they are to be answerable also that the pikes are kept clean, and always ready and fit for service.”[3]

Washington ordered on July 23, 1775 that “the people employed to make spears, are desired by the General to make four dozen of them immediately, thirteen feet in length, and the wood part a good deal more substantial than those already made, particularly in the New Hampshire Lines, are ridiculously short and light, and can answer no sort of purpose, no more are therefore to be made on the same model.”[4]

The Pennsylvania Committee of Safety recommended the use of pikes in August 1775 as follows:

It has been regretted by some great soldiers, particularly by Marshal Saxe [Saxe, 1696-1750, wrote Reveries on the Art of War, which has become a classic], that the use of pikes was ever laid aside; and many experienced officers at the present time agree with him in opinion, that it would be very advantageous in our modern wars to resume that weapon; its length reaching beyond the bayonet, and the compound force of the files (every man laying hold of the presented pike) rendering a charge made with them unsupportable by any Battalion armed only in the common manner. At this time, therefore, when the spirit of our people supplies more men than we can furnish with fire-arms, a deficiency which all the industry of our ingenious gunsmiths cannot suddenly supply, and our enemies having at the same time they were about sending regular Armies against undisciplined and half-armed farmers and tradesmen, with the most dastardly malice endeavoured to prevail on the other Powers of Europe not to sell us any arms and ammunition, the use of pikes in one or two rear ranks is recommended to the attention and consideration of our Battalions. Every smith can make these, and therefore the Country may soon be supplied with plenty of them. Marshal Saxe’s direction is, that the staff be fourteen feet in length, and the spear eighteen inches, thin and light; the staff to be made of pine, hollowed for the sake of lightness, and yet to retain a degree of stiffness; the whole not to weigh more than seven or eight pounds. When an army is to encamp, they may, he observes, be used as tent poles, and save the trouble of carrying them. The Committee of Safety will supply samples to those Battalions who are disposed to use them. Each pikeman to have a cutting sword, and, where it can be procured, a pistol.

Ordered, that a copy of the above be delivered to the Colonels of the different Battalions in this City [Philadelphia] and Districts; which was accordingly done.[5]

Riflemen were more susceptible to attack by cavalry and bayonet wielding infantry since rifles were slow to load and not equipped with bayonets. Washington sought to alleviate this problem by supplying riflemen with spears. In June of 1777 he wrote to Daniel Morgan informing him that he had “sent for spears, which I expect shortly to receive and deliver to you, as a defense against Horse; till you are furnished with these take care not to be caught in such a Situation as to give them any advantage over you.”[6]

A week later the spears arrived. Washington noted that they…

are very handy and will be useful to the Rifle Men. But they would be more conveniently carried, if they had a sling fixed to them, they should also have a spike in the but [sic] end to fix them in the ground and they would then serve as a rest for the Rifle. The iron plates which fix the spear head to the shaft, should be at least eighteen inches long to prevent the Shaft from being cut through, with a stroke of a Horseman’s Sword. Those only, intended for the Rifle Men, should be fixed with Slings and Spikes in the end, those for the Light Horse need neither. There will be 500 wanting for the Rifle Men, as quick as possible.[7]

General Charles Lee wrote Richard Henry Lee [Richard Henry Lee, no relation to Charles Lee, was a member of the Continental Congress from Virginia], April 12, 1776, reporting that he had been “conciliating your soldiers to the use of spears; we had a battalion out this day; two companies of the strongest and tallest, were armed with this weapon; they were formed something like the Triarii of the Romans [Triarii were one of the elements of the early Roman military legions of the early Roman Republic (509 BC – 107 BC), usually placed at the rear of battle formations], in the rear of the battalions, occasionally either to throw themselves into the intervals of the line, or to form a third, second, or front rank in close order. It has a fine effect to the eye, and the men in general seemed convinced of the utility of the arrangement.”[8]

General Lee wrote John Hancock, the President of the Continental Congress, April 19, 1776 that “the arrangement I have made of arming two companies of each battalion with spears, will render musket and bayonets less necessary; and the ease I find in reconciling the men to these kind of arms, is a flattering symptom of their spirit.” The troops he was referring to were Virginians.[9]

Later in the war when munitions flowed to the Colonies from France in large quantities the need for bows, arrows, pikes or spears diminished greatly. Thousands of pikes or spears had been manufactured. The number actually issued is not known. Research has not been able to document the issuance of bows and arrows to patriot forces. Whether Benjamin Franklin was successful in his support of bows and arrows remains to be discovered.

[1] Letter, Franklin to Charles Lee, February 11, 1776, in Langworthy, Edward, editor, Memoirs of Charles Lee, New York, T. Allen, 1793, p 154-155. Latin translation courtesy of my wife, Dr. Susan J. Harrington.

3 Comments

Franklin was wrong on a few of his accounts. To make a good bowman, you need a lot of time. There is a reason why the musket replaced the bow and arrow in European warfare. Even the Native Americans replaced the bow and arrow with firearms. In some cases tribes had completely lost the bow making skill due to their use of muskets. You’re absolutely correct in that he wrote that letter and that these weapons were proposed. That is obvious and I do not dispute the facts at all. It’s just they were last ditch weapons proposed due to the crisis on arms and ammunition.

The severe lack of gunpowder was a huge obstacle. As you noted, Hugh, the dates of these documents indicates the context they were written in and validates the importance of foreign aid to the colonies. The losses of 1776 created a situation where the trickle of gunpowder had failed to keep up with losses and battle consumption. Only the arrival of supplies sent from France via Beaumarchais and Silas Deane and the fictitious front company, Roderigue Hortalez and Company allowed the Americans to have the success at Saratoga in 1777.

Despite what Benjamin Franklin suggested as good advice, I have a real hard time envisioning American forces defeating the British in the Saratoga campaign with bows and arrows. Good work on the article. It really drives home how important the gunpowder supply was.

I doubt bows and arrows ever made it into the field. Spears and pikes however would be quite useful. Cavalry can’t stand up to 16 foot pike leveled at them. Spears for riflemen when those bayonet wielding redcoats get too close…far better than swinging a rifle like a club. Not everything every inventor comes up with is practical. But, then again things like the Turtle submersible…had a future. Also, remember the battle of the kegs!

I have come across an interesting item that should be an addendum to this article. Lt. Col. John George (“Shots Fired in Anger,” NRA, Washington, DC, 1981) states on page 534, writing about late 20th century soldiers “…not one rifleman in ten thousand can use his weapon to full advantage. The importance of skill vs. weapons design is well demonstrated by the fact that a fine competitive archer can shoot better with his bow and arrow than the average Infantry rifleman armed with a rifle.” Colonel George as a young infantry officer fought in the Pacific in WWII for three years; he was also a competitive shooter before and after the war. Maybe bows and arrows should have been tried in the American Revolution.