Dear Mr. History:

What is the true impact and legacy of the “Green Mountain Boys” and their commander, Colonel Ethan Allen? Some say they were an important colonial militia; others have called them a pack of wild, hard-drinking mountain men. While still others say that Allen was really a half-crazy, obnoxious, blowhard who should share credit with Benedict Arnold for seizing Fort Ticonderoga. And today there’s a furniture store named Ethan Allen. Who is right? Sincerely, Allen-Wrenched.

Dear Wrenched:

You say “wild, hard-drinking mountain men,” and “obnoxious blowhard” like those are bad things. Never mind. The story of Ethan Allen and the Green Mountain Boys is a fascinating one that touches on some of the basic themes of the Revolution. Let’s look at this piece by piece.

In the 1750s and 60’s, the New York and New Hampshire colonies issued competing land grants to settlers in the northwest frontier region, the area which later became Vermont. In 1764 King George III ruled that the area was part of New York, and the New York government planned to evict many Hampshire Grant settlers. However, the Hampshire Grant settlers believed that even if New York owned the area, the colony had no right to evict the land holders. To them, the Yorkers intended to destroy their livelihoods and deny their personal liberty by evicting them from the farms that they had carved from the wilderness. They believed that this gave them every right to defend themselves. In 1771 they resolved to resist New York control with a militia named the “Green Mountain Boys.” Land speculator Ethan Allen was elected their colonel and commander.

used by the Vermont National Guard. Photo by Amber Kinkaid used with permission.

Allen was 33, the patriarch of a fairly prosperous family from Connecticut, and somewhat read in the classics and philosophy. Though his Green Mountain Boys had only the most basic educations, most of them were also relatively responsible heads of farming households in their 20’s and 30’s. Allen was thirsty for fame, but considering them all wild, drunken mountain men would be incorrect.

But Allen and the Green Mountain Boys were certainly tough frontiersmen, and if we define the concept of “self defense” to mean “scaring the knee-breeches off the New Yorkers,” then they were great at their job. Beginning in around 1771, they launched a campaign of terror tactics such as threats, humiliation, and intimidation to chase-off any who attempted to exert New York control over the area, including land surveyors, law officials, and settlers.

For example, in July 1771, New York sheriff Henry Ten Eyck took a 150-man posse to evict the Hampshire settler James Breckinridge. An equal force of armed Green Mountain Boys gathered at Breckinridge’s in opposition. Ten Eyck attempted to break down Breckinridge’s door but the Green Mountain Boys leveled their muskets at him. Ten Eyck backed off, and his posse dispersed. In November 1773, many settlers in the town of Durham sided with New York. Allen threatened to “Lay all Durham in Ashes and leave every person in it a Corpse.” You have to give the man points for directness. Then Allen and a company of Green Mountain Boys kidnapped a Durham justice of the peace named Benjamin Spencer in the middle of the night. Allen convened a frontier court that found Spencer guilty of cozying up to the New Yorkers. Spencer’s sentence was the torching of his house (though only the roof burned). After that, most of Durham’s residents purchased land titles from New Hampshire. Another time, the Green Mountain Boys drove off the settler Charles Hutcheson, who received his land grant for service in the French & Indian War. While his soldiers set fire to Hutcheson’s house, Allen held the man by the collar and shouted, “Go your way now & complain to that Damned Scoundrel your Governor. God Damn your Governor, Laws, King, Council and Assembly.” Through multiple other acts like these, but never causing bloodshed, Allen and the Green Mountain Boys thwarted almost every attempt by New York officials to exert their influence from 1771 to 1775.

The concepts of self defense and personal liberty mattered little to the officials of New York, who expected the settlers to address their grievances through proper authorities. New York Governor William Tryon considered the Green Mountain Boys the “Bennington Mob,” and initially issued warrants for the arrest of Allen and his cohorts, with a £20 (about $3,000 today) reward for their capture. With Allen still at large and gaining control in late 1773, Tryon requested British soldiers to end the resistance. The Royal commander of the region, General Frederick Haldimand, declined to send troops to quiet “a few lawless vagabonds.” Tryon’s response was to issue a proclamation against the Green Mountain Boys for “atrocities” and he increased the reward for the arrest of Allen and other leaders to lofty sum of £100. His edict only gained him further ire from the Hampshire Grant settlers, as it came at the same time that Britain angered the Americans with its “Intolerable Acts.” Allen tied his local fight to the overall cause of American liberty, and the Green Mountain Boys’ solidified their control of the area. Historian Michael A. Bellesiles offers the analogy, “If the Grants equaled America, then New York was its Britain.”

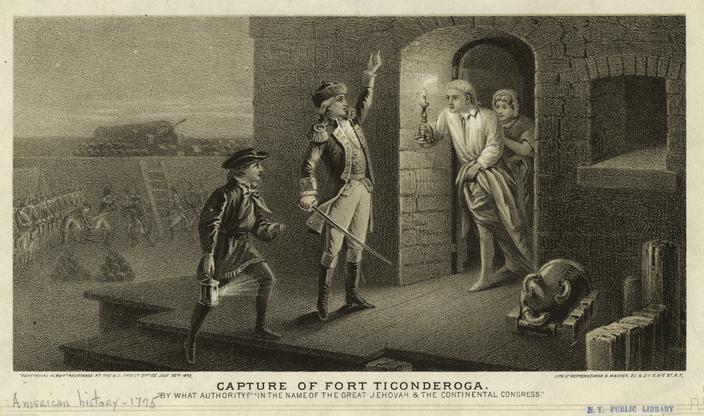

What about seizing Fort Ticonderoga? When Revolutionary hostilities opened in April 1775, Allen knew that the British forts on Lake Champlain – Fort Ticonderoga and Fort Crown Point – were the keys to controlling the area, and that the forts made easy targets after their years of neglect by the British. To secure the region for the Americans, and to hitch his wagon to the larger war, Allen planned to seize the Lake Champlain defenses with his Green Mountain Boys.

In early May 1775, in cooperation with the Connecticut Committee of Safety, Allen gathered about 130 Green Mountain Boys and about 60 Connecticut and Massachusetts militiamen on Lake Champlain to attack Fort Ticonderoga. They planned an assault by boat, but had none, and had to search for them along the lake. While they searched, Col. Benedict Arnold arrived at their camp with orders from Massachusetts to seize the fort. He demanded command of the attack. As if. There was no way the unknown and somewhat arrogant Arnold was going to win over the Green Mountain Boys. Besides, Arnold brought nothing to the fight except himself. Allen’s soldiers said that they would return home before they followed Arnold. Allen could easily have sent Arnold packing back to Massachusetts, but to soothe his bruised honor, Allen offered Arnold a joint command.

At night on May 10th, with Allen and Arnold leading them, about 85 Green Mountain Boys and Massachusetts men – that was all that could fit into the two boats they found – rowed quietly up to the base of Fort Ticonderoga. The isolated British garrison of about 50 men was not even aware that a war had started with the American colonies. Allen and Arnold strode into the fort’s main gate side by side. A sentry blocked their way and Allen knocked aside the soldier’s musket while the Green Mountain Boys clambered over the fort’s walls shouting, “No quarter!” Allen pointed his sword at a British soldier and demanded the location of the fort’s commander. The location revealed, he and Arnold bounded up the stairs to the commander’s quarters as Allen shouted “Come out of there you damned British rat!” The dazed officer surrendered the fort after Allen threatened to kill him. Another detachment of Green Mountain Boys seized Fort Crown Point the next day. On May 17th, Arnold did take a more active role when more Massachusetts troops arrived and they raided the British garrison at Fort St. Jean on the Richelieu River. But the only thing Arnold did at Fort Ticonderoga was tag along for the glory.

Was he a half-crazy, obnoxious blowhard? Possibly, but who hasn’t been at different times of our lives? Michael Bellesiles tells us that Allen gained prominence in the resistance to New York by thrusting himself forward when indecision existed, and the use of “threats, bluff, and outrageous self-exaggeration” as leadership techniques. Such bravado succeeded until the summer of 1775 when Allen decided to seize Montreal, Canada in a joint attack with about 200 Massachusetts militia under Major John Brown without orders from . . . anybody. When he moved against the city on September 25th, Brown’s force did not show up because they couldn’t get across the St. Lawrence River. Allen had once boasted, “with fifteen hundred men and a proper artillery, I will take Montreal.” But he attacked the city anyhow with about 100 men and no artillery against a force twice the size. You’re probably not surprised to learn that the attack failed and Allen was captured. That’s what bragging gets you.

Allen’s reputation for somewhat lunatic behavior grew during his time as a prisoner of war in a series of locations including on board British ships, England, Ireland, and Long Island. He continually fought with his captors, called himself a “conjuror,” shouted insults, and harangued them about the British mistakes in America. Allen once ripped out a ten-penny nail on his handcuffs with his teeth and chipped a tooth in the process. He said that he overheard one captor say, “Damn him, can he eat iron?” He was later placed on parole on Long Island. There, he became ill from his harsh treatment and depressed because of his separation from his family and the death of his son Joseph, from smallpox. Allen roamed around the parole area, drank heavily, and fought in local taverns, reliving his glory days to anyone who would listen. The British thought that he was crazier than a loon.

So what is his legacy? The British released Allen in 1778, possibly to their great relief, as part of a prisoner exchange. He returned to a hero’s welcome in Vermont and recalled, “I was to them as one rose from the dead.” Allen settled near present-day Burlington and in 1779, published his exploits in his memoirs, “A Narrative of Colonel Ethan Allen’s Captivity, written by Himself.” He recounted his adventures in heroic and thrilling style and the book was a best-seller. The Narrative established the Allen mythology and legacy as both a gallant, dedicated Revolutionary leader and an untamed product of the Green Mountains – which is probably exactly what he wished. Vermont had claimed the status of an independent Republic in 1777, and Allen unsuccessfully petitioned the Continental Congress for its recognition. Between 1780 and 1783 he negotiated with Britain for Vermont to become a Crown province, which was probably unwise. Congress charged Allen with treason but never pursued prosecution. In 1785 he published a second book, Reason: the Only Oracle of Man, which attacked Christianity. Probably a bit too radical for its time, it was a complete failure. Allen focused on farming, continued writing pamphlets, and sold off some of his own land, but was rarely flush with money. He died in 1789, possibly from a stroke, or from falling drunk out of a sleigh, depending on the story. Either way, it was unfortunately only two years before Vermont became the fourteenth state. Despite his setbacks, many Americans still regarded Allen as a hero of the Revolution, and his death was national news.

Allen and the Green Mountain Boys deserve their place in American history for their role in the founding of Vermont and the capture of Fort Ticonderoga, which gained invaluable artillery for the Continental Army. Sure, they burned some houses, but that’s the trouble with rebellions – one person’s freedom fighter is often another’s dangerous criminal. Overall, Allen lived the concepts of local and individual liberties, which were two important Revolutionary themes.

By the way, the Green Mountain Boys also fought in the Saratoga campaign, and today’s Vermont Army National Guard and Air National Guard still carries the moniker “Green Mountain Boys.” But they don’t burn houses anymore.

The complete story of Allen, the Green Mountain Boys, and the founding of Vermont is fascinating as well as complicated. To read up on them yourself, check out, Revolutionary Outlaws: Ethan Allen and the Struggle for Independence on the Early American Frontier, by Michael A. Bellesiles, or Ethan Allen: His Life and Times, by Willard Sterne Randall.

And I’m not aware of any connection Allen had to furniture, except that I’m sure he probably used it from time to time.

13 Comments

I grew up in South Hero, Vermont, where Ethan Allen is said to have enjoyed his last meal (and evening of drinking). The legend was that he suffered an accident or stroke on the trip home.

The stone inn (built, I believe, by Ebenezer Allen), where Ethan is supposed to have last supped, still stands in South Hero, and now houses a bank branch.

From what I could discover, Ethan Allen succeeded in popularizing himself during the Revolution, and was well-regarded by his men, despite (or perhaps because of) his flamboyant nature.

The strategic importance of Allen’s seizure of Ticonderoga shouldn’t be overlooked, either. The loss of this and the other forts along Lake Champlain denied British forces the use of the lake as an easy means of transporting troops and materiel via Montreal, through Lake George and down the Hudson to New York City.

Even more directly, the cannon stripped out of Fort Ticonderoga were dragged overland to Boston, where they were placed on the high ground overlooking that city, and helped to break the British occupation there.

Allen was a complex and contradictory character, but I think that most of us would enjoy an evening of storytelling – and drinking – with him at our tables.

Right you are Lars!

Allen’s personality was perhaps a bit too big. In 1775, before the ill-fated attack on Montreal, the Committes of Safety that represented the Hampshire Grants area voted Allen’s cousin, Seth Warner, as the new commander of the Green Mountain Boys, possibly because Allen was too much of rogue. Warner was a strong leader, and steadier than the fiery Allen. Allen was relegated to command of a mere detachment.

Still, I’d certainly enjoy a drink with Allen. I also have some noisy neighbors I’d like him to talk to.

A flamboyant leader who can attract (and work effectively with) lieutenants who can provide a counterweight to his own failings is all the more admirable, in my opinion. Flamboyance, in itself, is not always a fatal character flaw.

Seth Warner, Remember Baker and some of the other Allen brothers all helped Ethan Allen in leading a remarkably effective militia, that not only provided some of the unsung miracles that led to the success of the Revolution, but also helped to defend the Republic of Vermont from the Yorkers and the other colonists. 🙂

There are any number of figures from that time with whom I suspect we’d all love to knock back a few mugs of cider or ale, not only to better understand them as historical figures, but also for the sheer enjoyment of them as human beings.

Right you are again, Lars – thanks for adding your insight and raising some great points!

A couple comments: 1)Up until well into the 20th century, Vermont had two parts–east and west sides divided by the Green Mts. (modern travel methods isolate us from geographical difficulties). Ethan and the “Arlington junta” garnered most of their support from the west side while a good portion of the east side actually supported NY claims. It’s complicated.

2)With regard to the Haldimand negotiations to link Vermont with British-controlled Canada–while secret and few in numbers, others besides Ethan had their hands in it. Further, neither side knew what those Vermonters had in mind nor did they trust them. It should be pointed out that Ethan et al owned nearly 80,000 acres–most of it along Lake Champlain in the area of Burlington–and had plans for more than just selling it to settlers. They had created a trading company and any economic activity would be much easier–read as more profitable–by going down the lake to Montreal and Quebec City rather than to Boston or New York (that remains true through much of the 19th-century until railroads make overland transport more feasible). Nobody knows for sure if they really wanted to put themselves under Brit governance or used the negotiations as leverage for admission to Congress and the united States. It’s complicated.

3)To my knowledge, Vermont never referred to itself as a republic. Between 1777 and 1791, it existed as an “independent state.”

Glad to see a good intro to that part of Vermont’s early history on this site. Thanks.

Hi Mr. History!

I enjoyed this — thank you. One question…why did Allen want Vermont to become a Crown province after all he’d been through with the British?

British newspaper reports that Ethan Allen actually joined the British side!

February 1, 1781 Leeds Intelligencer, West Yorkshire, England

“The late accounts received from Albany informs us that Col. Ethan Allen with upwards of 600 effective men, had join the Royal garrison at Ticonderoga.”

February 22, 1781 Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette

“There is every reason to suppose that Ethan Allen had quitted the rebel cause.”

Based upon these British accounts, along with contemporaneous correspondence from Canadian and American sources, clearly Ethan Allen and other Vermont leaders actively negotiated with the British. However, the British loss at Yorktown greatly inhibited their completion.

Interesting question, Tina, and various forms of it have frustrated VT historians for centuries–people asked the question while the negotiations took place.

First thing to understand is that Ethan Allen actually played a lesser role in the talks. The British made initial contact with him but he backed away early on once the secrecy of the negotiations fell apart. Most of the talking–to the Britsh, Congress, and the rest of Vermont–fell to the sly mind and mouth of the man arguably most responsible for Vermont’s existence, Ethan’s brother, Ira.

The challenge to answering the question lies in the fact that nobody, then or now, can definitively show what the Allens, VT governor Thomas Chittenden, and the few other Vermonters involved actually had in mind. No documents have come to light explaining their thoughts so any ideas are based solely on circumstantial evidence.

Knowing the economic situation of the “Arlington junta”–large holdings along Lake Champlain with easy trade routes to/through Canada–and their political investment in Vermont–bolstered at the time by towns on the east side of the Connecticut River and the west side of Lake Champlain joining Vermont (Charlestown, NH, served as capital of Vermont for a bit)–many, myself included, feel the Allens, etc., wanted to protect their situation. Congress had recently made an unacceptable offer to resolve the conflicts with NY and NH so, when the question of joining Canada came along these men took a chance.

The negotiations sputtered along for a few months and pretty much came to an end when Washington, himself, told Vermont that, if they would reject the NY and NH towns, he would see to Vermont’s admission to Congress. Vermont dumped the towns but then learned that Washington couldn’t deliver on his offer. By opening their arms toward Congress, the Vermont negotiators lost their advantage with the British. Privately, Haldimand and other Crown powers admitted that they would like to have seen Vermont join them but they never really pursued it any further.

One last note: I’m not so sure that Ethan Allen felt the British had really mistreated him. His memoirs of the captivity vacilate back and forth between bad handling and fine treatment depending on the point he tried to make at the time. In the end, I suspect he actually felt his ego rather gratified by the British view of him as something of a notable figure and by their demand of the equivalency of a colonel, if I remember rightly, for his exchange.

Thanks, Mike!

Mr. Schellhammer, excellent piece……I really enjoyed reading this.

Great story, well told

Ethan Allen was eventually exchanged for Lt Col Archibald Campbell of the 71st (Highland) Regiment who was initially held prisoner of war in Reading Mass but later moved to the Concord Mass gaol. Campbell was said to have been, at one time, the highest ranking British prisoner of war. So his exchange for Allen gives you a good idea of the importance that the British gave to Allen.

Surely the exchange of Allen for Campbell only shows the importance that the British believed the rebels attached to Allen. I might well have had nothing whatsoever to do with the importance (if any) that they themselves attached to him.