When Congress, in late June 1775, authorized the raising of six rifle companies from Pennsylvania and Virginia, George Merchant enlisted as a private. He was indistinguishable from the other men and would not be recalled in modern times except for the extraordinary events through which he passed and the strange part he was to play in the war. [1]

At this time the British forces in Boston were under siege by the Patriots. The rifle companies marched to join the Patriot army surrounding Boston. There, the riflemen had little to do other than taking the occasional shot at a British soldier or officer.

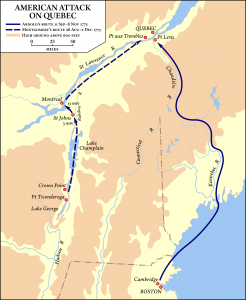

While the stalemate between the British behind their defensive positions in Boston and the Patriots encircling them wore on plans were being developed by the Patriots for an ambitious and bold move on Canada. The operation included a two pronged invasion of Canada. One force, of about 3000 men, under Brigadier General Richard Montgomery was to take the standard route to Canada via New York’s Lake George and Lake Champlain to attack Montreal.

The second force, of 1100 men under General Benedict Arnold, would take a very difficult and mostly unexplored route going North up Maine’s Kennebec River then crossing to the Chaudière River and on to the St. Lawrence River and Quebec. This route was so unusual that it was hoped the enemy would be taken by surprise.

The little army, including George Merchant, left Cambridge on September 13th to march to Brunswick where they would board ships to take them to the Kennebec and as far upstream as possible. They then boarded 200 flat bottomed bateaux to proceed up the river. This proved to be far more difficult than had been envisioned. The men struggled to drag and sometimes carry the bateaux and their provisions up the river. Captain Daniel Morgan, commanding the three rifle companies selected for the expedition, took the lead ahead of the infantry and an artillery company with one small cannon. It was part of their task to clear the river of obstructions to make it easier for those coming behind.

Soon, the entire expedition was confronted by a strong current as the men struggled, day after day, often waist deep in water, hauling the bateaux laboriously upstream over rocks and past waterfalls. Within a month the number of men who had taken sick or deserted was considerable. Morale was low. However, the worst was yet to come.

When the streams and lakes petered out the bateaux had to be unloaded and then the baggage and the bateaux had to be carried through ravines, woods and swamps. This required many exhausting trips on foot back and forth to gain a few miles. Rain, followed by snow, made the trek even more cold and miserable. Food became scarce as many supplies were destroyed by having been soaked with water.

Eventually, the Chaudière River was reached. Morgan, and the few remaining bateaux, went downriver only to be upset in rapids losing all the bateaux and most of their contents. The men struggled to shore. Faced with starvation, moccasins, cartridge boxes and leather of all kinds were boiled and eaten. The men scavenged for roots, berries, anything edible. Many men sickened, some died of exposure or drowning, and some deserted. The situation was saved by Benedict Arnold who had gone ahead of the main body of the expedition. He sent cattle upriver as well as boats carrying food.

The march to Quebec is one of the great endurance epics of the Revolutionary War. The ordeals these men suffered are a chronicle of misery and endurance surpassing the far more famous Valley Forge.[2]

The remnants of Arnold’s American army, now consisting of only 500 men fit for duty, reached the St. Lawrence on November 8th. On the night of November 13th Arnold led his little army stealthily crossed the St. Lawrence River passing between two British warships. He now faced the fortified city of Quebec.

On the morning of November 14th George Merchant was on sentry duty. About noon he was captured and taken into the city of Quebec. The exact circumstances of his capture are unknown. He did not fire his rifle, however in his defense it is possible he may have tried to fire and the rifle misfired. General Arnold wrote on the 14th that “…the enemy found means to make prisoner of one of our out sentinels.” And, “…yesterday [this must have been written after midnight] they took one of our sentinels, through his carelessness.”[3]

The most colorful, and probably the least accurate, account of the capture of George Merchant was written 36 years after the incident by John Joseph Henry. He relates, “It turned out that a Mr. Ogden, a cadet from Jersey, a large and handsome young man, in favor with Arnold, had been authorized to place the sentinels that day. He did place them, most stupidly. George Merchant, of Morgan’s, a man who would at any time, give him fair-play, have sold his life dearly, he stationed in a thicket, within view of the enemy. At the time of placing him, when at his post, he was out of sight of the garrison; but the mischief was, (although he could not be seen,) he could see no one approach; he was taken absolutely unaware of danger. A sergeant of the ‘seventh,’ who, from the manner of the thing, must have been clever, accompanied by a few privates, slily [sic] creeping through the streets of the suburbs of St. John, and then under the cover of bushes, sprung upon the devoted Merchant even before he had time to cock his rifle. Merchant was a tall and handsome Virginian. In a few days, he, hunting-shirt and all, was sent to England, probably as a finished specimen of the riflemen of the colonies. The government there very liberally sent him home in the following year. The capture of Merchant grieved us, and brought us within a few hundred yards of the city.”[4]

George Merchant undoubtedly was tired having crossed the river the night before. Also, in the previous weeks he had endured tremendous hardship. The possibility exists that he may have deserted to the enemy. Or, perhaps more likely, he fell asleep at his post and was captured. Whatever the circumstances, he was now in the hands of the enemy.[5]

On the 22nd of November, a week after his capture, George Merchant was placed aboard a ship, ironically named Liberty, bound for Bristol, England. The Liberty arrived a day or two prior to December 27th.[6]

Within days, on December 30, 1775, George Merchant was “discharged from his confinement, there not being sufficient evidence to detain him in goal.”[7] He was captured bearing arms against the King yet he was released for lack of evidence. One cannot help but wonder if something unusual was taking place.

George Merchant surfaces again in early May 1776. From Portsmouth, New Hampshire, John Langdon, a member of the second Continental Congress, wrote George Washington on May 10th an astonishing letter:

“This will be handed you by George Merchant, who says he is one of the riflemen that went from Cambridge under General Arnold to attack Quebeck; he was taken prisoner crossing the river at that place, sent to England in irons, has just returned by way of Halifax, from when he made his escape, with some others, in a small boat. He arrived at Old-York yesterday, when he informed the Committee of that place of his having letters from England, which he had concealed in the waistband of his breeches. They thought fit to open the letters, and sent them on to the Committee of this place, who have directed me to despatch the man with the letters to Congress, after having called on you in the way there; I have, therefore, furnished him with necessaries, and given strict directions to proceed with all possible despatch to Head-Quarters at New York, as express to your Excellency, with the enclosed letters; as they contain matters of importance, no doubt you will think proper to forward them to Congress.”[8]

Washington met with George Merchant on May 18, read the documents, and immediately sent Merchant on his way to Philadelphia. Writing John Hancock, President of Congress, Washington described Merchant’s documents as, “sundry matters of Intelligence of the most Interesting nature.” And, “as the consideration of them may lead to important consequences and the adoption of several measures in the military line, I have thought it advisable for General [Horatio] Gates to attend Congress who will follow to morrow….”

George Merchant had carried copies of the treaties made by George III with the Duke of Brunswick, the Landgrave of Hesse Cassel, and the Count of Hanau for troops, commonly known as “Hessians,” to be hired and sent to America. In addition, Merchant carried unsigned letters believed to be from Arthur Lee, dated February 13th and 14th with intelligence about the British war plans. This clearly was news of “the most Interesting nature.”

Congress ordered that the documents be published in the newspapers to arouse the citizens. The treaties and letters appeared in the newspapers immediately and were widely copied so literally every literate citizen would have had the opportunity to read them in a very short time.[9]

Merchant was granted his regular pay from the date of his capture until June 15th by Congress. He would also receive a gratuity of $100.[10] Merchant then fades into history but the documents he carried do not.

The copies of the treaties with the Germans confirmed rumors that had been circulating for many months that the King was planning to hire mercenaries to fight his own subjects. While it was gratifying to know for certain that this was taking place even without the copies of the treaties the arrangement would be public knowledge within a few weeks as the British in England were not keeping it secret. The treaties may have been sent to America with the thought of giving Congress and George Washington a heads-up so preparations could be made. Or, more deviously, the treaties could have been sent with the thought that the news of many thousands of Germans coming to fight would “shock and awe” the Americans into negotiating a peace.

The letters raise other questions. As would be expected for letters containing secret intelligence sent they are written in a disguised handwriting. The are accepted to be written by Arthur Lee, an American diplomat in London. The letters are addressed to Benjamin Franklin and Lieutenant-Governor Colden of New York.

As Colden was a loyalist it is likely Lee never had any intention of the letters actually going to Colden but used his name in case the letters were intercepted. Using Franklin’s name may also have been a decoy. In addition, it may be that George Merchant was given instructions as to whom the letters should be delivered but that he was forced to turn them over before reaching those persons.

The letters advise that 30,000 British and German troops would be in North America for the 1776 campaign. Most importantly, the letters relate that military operations would be in Canada, Boston and Virginia. However, the 1776 campaign was aimed at New York and Charleston, South Carolina. Clearly, Arthur Lee had been misled by false information that had been fed to him by the British.[11]

Caesar Rodney, a member of Congress, wrote his brother, Thomas, about Merchant saying, “…he was sent to London and put in Bridewell [prison in London] in irons. Sawbridge (the Lord Mayor) [John Sawbridge] went to him, examined him and had him immediately discharged and sent down to Bristol where a number of Gentlemen pronounced [procured?] him a passage to Halifax. He left Bristol the 24th of March, arrived in this city [Philadelphia] the day before yesterday [May 20] and tho’ searched at Halifax 2 or 3 times brought undiscovered a number of letters and newspapers to the Congress by which we are possessed of all their plans for the destruction of America….”[12]

This letter raises some interesting questions about Merchant and his story. Clearly, all the information comes from Merchant himself as there are no other witnesses to his activities. Was his capture actually a desertion. Apparently he is sent to England, “in irons,” to be hanged. The visit by the Lord Mayor of London, who was a known American sympathizer, may be credible but that the Lord Mayor was able to arrange Merchant’s release is more difficult to accept as Merchant’s offenses against the crown would not have had anything to do with London. One would like to know who the “Gentlemen” in Bristol were who arranged for his passage to Halifax and what he was doing, and who he was meeting, in England during the 10 weeks before he sailed.

Rodney writes that Merchant was searched “at Halifax 2 or 3 times” yet the papers he carried sewn into his breeches were not found. Clearly, the searches were not very thorough or perhaps the documents were allowed to pass “undiscovered.” It must be remembered, too, that Merchant claimed he was in Halifax for 10 days until he was able to “escape” in a “small boat.” What was he doing in those 10 days and who did he meet, if anyone. The word “escape” seems peculiar. Since he was released or discharged, with no mention of parole where he would need to be exchanged for a British prisoner in American hands, it would seem that he should have been a free man and could book passage to Halifax openly, and then free to leave Halifax.

It may be that Merchant was freed in England to act as a messenger to carry documents to Congress as part of a wider plan to plant disinformation in Congress. Or, was something darker and more sinister at work?

There is much we will never know about George Merchant and the peculiar occurrences in which he was involved after crossing the St. Lawrence River in November 1775 through May of 1776 in Philadelphia. It is regrettable that there is no published interview with him that might provide more details, more facts that could be verified….or disproven.

[1] The author wishes to thank Paul Hornak for assistance with research and sharing his insights and enthusiasm.

[2] Roberts, Kenneth, March to Quebec, Journals of the Members of Arnold’s Expedition, New York, Doubleday, Doran & Company, 1938. All extant diaries of the March are included in this volume.

[3] Roberts, Kenneth, March to Quebec, Journals of the Members of Arnold’s Expedition, New York, Doubleday, Doran & Company, 1938. Letters of Benedict Arnold to Gen. Montgomery and Captain Oliver Hanchet, November 14, 1775, p. 87-88.

[5] Secondary sources often state that a rifleman, sometimes naming George Merchant specifically, was sent to England on order of General Howe allegedly because Howe complained of “terrible guns of the rebels.” The story is that Howe wanted the rifleman to give marksmanship demonstrations. The author has discovered no evidence of any such capture or demonstrations in England. The rifle was not a new invention. For typical account of this story see Sawyer, Charles Winthrop, Firearms in American History, Boston, published by Sawyer, 1910, p. 80-81.

[9] See Connecticut Courant, [Hartford] May 20, 1776; Pennsylvania Evening Post, [Philadelphia], May 23, 1776, May 25, 1776; New York Journal, May 23, 1776; Pennsylvania Journal, May 24, 1776; Pennsylvania Ledger, May 25, 1776; Pennsylvania Packet, May 27, 1776.

Featured image: Montreal, 25 September 1775. Source: U.S. Army Center of Military History

Recent Articles

Supplying the Means: The Role of Robert Morris in the Yorktown Campaign

Revolution Road! JAR and Trucking Radio Legend Dave Nemo

Those Deceitful Sages: Pope Pius VI, Rome, and the American Revolution

Recent Comments

"Texas and the American..."

Mr. Villarreal I would like to talk to you about Tejanos who...

"Trojan Horse on the..."

Thank you Eric! I should say that I have enjoyed your work...

"Trojan Horse on the..."

Great article. Love those events that mattered mightily to participants but often...