“It may be doubted whether so small a number of men ever employed so short a space of time with greater and more lasting effects upon the history of the world.” -British Historian George Otto Trevelyan

After firing-off a few ineffectual shots, the Hessian pickets turned tail and bolted south into the small town of Trenton, New Jersey—loudly spreading the alarm. Immediately on their heels, at the “long trot”—despite driving sleet that cut like a knife—stormed the ragged American advance party. The fast-moving Virginians (a company of the Third Regiment under Capt. William Washington and his young lieutenant), quickly took up a position on a small hillock at the “V” intersection of King and Queen Streets. They sent a shower of lead whistling after their enemies.

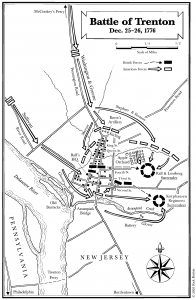

Trenton—that early morning of December 26, 1776—was little more than several dozen houses lining the two main parallel streets, King and Queen, which ran south from their intersection for a few hundred yards until reaching Assapink Creek. It was Gen. George Washington’s determination to destroy the village’s Hessian garrison. To do so he needed to eject the enemy force from Trenton.

Responding to the picket firing, half-awake German grenadiers of the Rahl Regiment stumbled out of their quarters in the town and attempted to form ranks on King Street. Officers shouted at them to ignore the abysmal weather and get into position. Well-trained in traditional European warfare, the mercenaries were startled by the rapid approach of the American rabble, and their wild appearance. Their assailants were filthy, barely covered in tattered uniforms, and amazingly—in defiance of the season—some were barefoot. Reddened snow marked their aggressive steps.

The Virginians surged forward, firing as they came. Crouching behind the cover of a tanyard fence Washington and his youthful lieutenant directed their riflemen to volley into the despised Hessians. Several dark blue-coated Germans, fumbling with their dampened firelocks, screamed and tumbled into the snow. In return the scattered enemy musketry flew high, whizzing over the Virginians.

Behind them the intersection of King and Queen was choked with rebel soldiers. Additional Third Virginia men pushed their way into the town. Manhandled American cannon were sighted down King Street and began belching grapeshot, the blasts echoing along the narrow roadway between Trenton’s homes. Shutters, windows, and dooryard fences shattered under the force of the iron hail. More Hessians fell.

Moments later, however, their defense was bolstered. Days earlier the German commander, Col. Johann Rahl, had placed two of his cannon—brass three-pounders—in front of his headquarters on King Street. Now their Hessian crews came running, carrying the rammers and ammunition. With a fury the cannoneers began loading the fieldpieces, the grenadiers on the street forming to either side. Those guns, once they opened fire, would add new weight to the German side of the argument.

The critical moment had arrived. Both sides understood the situation. For General Washington’s plan to succeed the German force on King Street had to be broken-up: the three-pounders must not be allowed to fire. Without hesitation Captain Washington and his lieutenant decided on a bold plan. Instantly they ordered their Virginians to rise, and rush the enemy artillery. “The American riflemen paused only once in their charge,” wrote historian Richard Hanser. “At a command from their leaders, they halted, sank down on one knee, took careful aim, and sent a withering volley at the Hessians.”

When they continued forward, reaching for their hatchets and long knives, Captain Washington fell wounded—hit in both hands—and command of the company devolved on his young lieutenant, eighteen-year-old James Monroe, future president of the United States. He shouted for his men to take the cannon, reminding them of General Washington’s countersign for the engagement—”Victory or Death.”

James Monroe is well-remembered as our nation’s fifth chief executive, the president who issued the Monroe Doctrine. His eight years in office—1817 to 1825—are today recalled as “the era of good feelings.” Few Americans, however, remember his service in the army during our war for independence. At the Battle of Trenton, New Jersey—which many consider one of the war’s pivotal actions—James Monroe was in the thick of the fighting. On King Street, with a courage that foretold of his later self-assurance, the young lieutenant helped lead his company into the very jaws of death. For the balance of his days Monroe looked back on the engagement as one of his proudest moments.

James Monroe was born in Westmoreland County, Virginia, on the Northern Neck, on April 28, 1758. He began his schooling at Campbelltown, a local boy’s academy, then entered William and Mary—in Williamsburg, the colonial capital—in 1774.

Williamsburg that year was simply abuzz with politics. A mere two weeks before Monroe’s arrival, the Virginia House of Burgesses—in response to England’s “Intolerable Acts”—ordered, wrote historian Emily Salmon, “a day of fasting, humiliation, and prayer and adopted resolutions denouncing the coercive acts of Parliament.” When the royal governor—John Murray, the earl of Dunmore—dissolved the assembly, the Virginians met in Williamsburg’s Raleigh Tavern and called upon the other colonies to send representatives to a congress in Philadelphia.

Serious study was extremely difficult for Monroe in the midst of this world-shattering turmoil. The opening actions of the Revolution were fought at Lexington and Concord, Massachusetts, on April 19, 1775. The following day in Virginia, Governor Dunmore attempted to reassert his authority by ordering Royal Marines to seize a store of gunpowder belonging to the city of Williamsburg. In response to this outrage, Virginians from all across the Old Dominion rose up in armed, organized bodies and marched against the royal capital. Rattled by this show of force, Dunmore respectfully offered payment for the powder.

Despite concern voiced by the institution’s professors, the William and Mary students now got directly involved in the capital’s day-to-day turmoil. When one of the student leaders organized a military unit James Monroe purchased a weapon and joined up. In June of 1775 the ties to the mother country were permanently severed when the Virginia Burgesses rejected England’s conciliatory resolves and established a Committee of Public Safety to run the colony. Dunmore retreated to the security of a heavily armed English warship.

The war in Virginia was on. On the twenty-fourth of June Monroe participated in a surprise attack on the Governor’s palace led by Theodorick Bland, Jr. Finding no opposition the small force of twenty-five men captured 200 muskets and 300 swords. These much-needed arms were handed over to the local militia. On New Year’s Day, 1776, a British fleet bombarded Norfolk, Virginia, and Redcoats came ashore to capture military supplies and burn buildings. Fighting raged through the night while the port city burned.

James Monroe officially joined the revolutionary effort in the spring of 1776. Unable to stay out of the stirring events whirling around Williamsburg, the future president enlisted as a cadet in the Third Virginia Infantry commanded by Col. Hugh Mercer. War fever was at high pitch and the ranks of the unit filled quickly. Perhaps because of his status as a college attendee, Monroe was soon made a lieutenant.

Throughout the spring and into summer the Third Virginia trained in the farm fields outside of Williamsburg. Rugged and enthusiastic, eighteen-year-old Lieut. James Monroe adapted well to the rigors of military life. “Slightly over six feet tall, broad-shouldered, with a massive if somewhat rawboned frame,” wrote biographer Harry Ammon, “he was an impressive figure.”

In August of 1776 the Third Virginia received orders to reinforce Gen. George Washington’s beleaguered army in New York. Outnumbered by a British force of 32,000 that had recently landed on Staten Island, the American general, with only 20,000 fit for duty, was desperate for more men. His position seemed untenable. The British made short work of the situation. Washington was defeated at the Battle of Long Island on August 27. Two nights later, under cover of heavy fog, he retreated to the island of Manhattan. On Sunday, September 15, Washington’s inexperienced troops were routed as he attempted to withdraw them north out of New York city. Once halted, the dispirited American army took up a strong defensive position on Harlem Heights. The Third Virginia joined General Washington’s battered forces that same day. Seven hundred strong, the regiment was now under the command of Col. George Weedon of Fredericksburg. Lieutenant Monroe was second in command of the seventh company under Capt. William Washington, a distant relative of the general’s.

It’s possible that James Monroe first saw action the very next morning. As the sun rose on September 16, 1776, the quiet between the opposing forces was broken by British buglers insolently sounding the fox-hunters’ call: “Fox in sight, and on the run!” The Third Virginia men, many of them hunters themselves, felt the insult’s sting and longed for a chance to face the enemy. In that morning’s Battle of Harlem Heights—a small affair, but a morale-raising American victory—a detachment of Monroe’s regiment, including perhaps the young lieutenant himself, was sent in as a reinforcement. The unit acquitted itself well in this, its first fight; standing firm and trading volleys with the heretofore invincible Hessians.

In early October the British juggernaut was again set in motion. The Americans were forced from Harlem Heights to New Rochelle—from New Rochelle to White Plains. From White Plains General Washington withdrew most of his army across the Hudson, to New Jersey. In mid-November he began his disastrous retreat southwestward across the Garden State. Enlistments in the American army were expiring, and the desertion rate was high. The situation was extremely grim. Washington retreated to Newark, and from there, on November 22, to Brunswick. Thinking ahead, the general ordered that all boats on the Delaware River—especially the forty to sixty-foot-long Durham freight boats—be collected at Trenton. When the last of Washington’s ragged little band, less than 3,000 men, was finally ferried over the river the morning of December 8, pursuing Hessian grenadiers entered Trenton with great pomp and circumstance—their flags flying and music playing. It had been a narrow escape.

With the British forces in possession of New Jersey, Philadelphia threatened, the winter fast advancing, and his outnumbered army shivering around its campfires, General Washington had but few options. “Some enterprise must be undertaken in our present circumstances,” Col. Joseph Reed wrote Washington on December 22, “or we must give up the cause. . . . Our affairs are hastening fast to ruin if we do not retrieve them by some happy event.”

The “happy event” that Washington conceived was a surprise attack on the 1,500-man Hessian force stationed at Trenton. He determined to hit them in the early hours of December 26, the day after Christmas. The Germans, Washington understood, were very fond of celebrating the season. Also, the American general knew—thanks to his spies—that the commander at Trenton, Col. Johann Rahl, was averse to winter fighting and overconfident. He had referred to the rebels as “a miserable lot” and “country clowns.” Washington planned to catch Rahl with his guard down.

Capt. William Washington’s company of the Third Virginia, including Lieutenant Monroe, was one of the first units to traverse the ice-clogged Delaware River. “After crossing the river,” Monroe later remembered, “I was sent with my command to the intersection of the Pennytown and Maiden Head roads, with strict orders to let no one pass until I was ordered forward. Whilst occupying the position, the resident of the dwelling [hearing a commotion] came out in the dark to learn the cause. . . . He was violent . . . and very profane, and wanted to know what we were doing there [on] such a stormy night. . . . When he discovered that we were American soldiers . . . he returned to the house and brought us some victuals. He said to me, ‘I know something is to be done, and I am going with you. I am a doctor, and I may help some poor fellow.'” When Monroe and Captain Washington received word to “hasten to Trenton” the good doctor—whose last name was Riker—went with them. His later presence, in Monroe’s time of need, some would call divine providence.

Weedon’s Third Virginia was given the task of spearheading the attack on Trenton from the north. The company under Captain Washington and Lieutenant Monroe was the vanguard. As they trotted forward, the frigid sleet in their faces, they could hear firing on the opposite side of town. General Washington had detached a portion of his 2,400-man force, under Gen. John Sullivan, to strike the Hessians from the south and cut off their retreat. Sullivan was hitting them right on time.

When Monroe’s men shoved back the German pickets other Hessians began spilling from their barracks. Some managed to pull off a few rounds. As the Virginians came under fire they wisely took advantage of whatever cover they could find. They returned fire from upstairs windows, from the corners of buildings, and from behind the tanyard fence. With reinforcements advancing down King Street to their assistance, they felt confident of victory.

The threat of the Hessian artillery, however, changed all that. To stop the mercenaries from bringing them into play Monroe’s company charged. When Captain Washington was shot “the command fell on me,” Monroe later wrote, “and soon after, I was shot through by a ball which grazed my breast. I was carried . . . to the room where Captain Washington was under the care of two surgeons. . . .” The ball had done much more than “grazed” the young Monroe, however, it had pierced his chest and severed an artery. Blood fountained-up through his uniform. “I would have bled to death,” he later admitted, “if this doctor [Riker] had not been near and promptly taken up the artery.” Indeed, if not for Dr. Riker, wrote Hanser, “the future fifth president of the United States would have perished, at the age of eighteen, in a pool of blood on a slushy street in Trenton, New Jersey.” (Monroe, unfortunately, never learned the first name of the man who had saved his life.)

Nonetheless, despite the loss of officers, the attack was a tremendous success. The Virginians, wrote Monroe, “rushed forward . . . and put the troops around the cannon to flight, and took possession of them.” From the streets of Trenton the Hessians fled east into an orchard. There the rattled fugitives were confronted on three sides by advancing Americans. The chilly waters of Assapink Creek sealed their last avenue of withdrawal.

“Our Men pushed on with such Rapidity that they soon carried four pieces of Cannon out of Six,” General Washington wrote on December 28, “Surrounded the Enemy and obliged 30 Officers and 886 privates to lay down their Arms without firing a Shot. . . . The Enemy had between 20 and 30 killed.” Colonel Rahl had been mortally wounded attempting to lead a bayonet charge back into Trenton. On the rebel side two officers, Monroe and Washington, and three privates were wounded. Two American soldiers were later found frozen to death along the route of march from the Delaware.

According to a staff officer who witnessed the action, the results “will rejoice the hearts of our friends everywhere and give new life to our hitherto waning fortunes. . . . [General Washington] pounced upon the Hessians like an eagle upon a hen. . . .” The English agreed. “All our hopes were blasted by the unhappy affair at Trenton,” commented Lord Germaine. “The Hessians will be no longer terrible,” wrote another member of the British government, “and the spirits of the Americans will rise amazingly.”

In this pivotal action of the American Revolution, Lieut. James Monroe had played an important role. “The capture of the two Hessian cannon was, in fact, a turning point of the Battle of Trenton,” penned Hanser. “The clearing of the upper end of King Street permitted George Washington to complete a maneuver” that inevitably led to the German surrender. “These particular acts of gallantry have never been noticed, and yet could not have been too highly appreciated,” wrote Gen. James Wilkinson, “for if the enemy had got his artillery into operation in a narrow street, it might have checked our movement and given him time to reflect and reform.”

For his conspicuous gallantry Monroe was rewarded. “I take occasion to express the high opinion I have of his worth,” wrote Gen. George Washington of the young officer. “The zeal he discovered by entering the service at an early period, the character he supported in his regiment, and the manner in which he distinguished himself at Trenton . . . induced me to appoint him to a captaincy. . . .”

James Monroe’s army career would continue—and he would eventually reach the rank of lieutenant colonel—but in his later life nothing shone so brilliantly in his memory as the decisive action on King Street the morning of December 26, 1776. During an 1817 tour of the country the fifty-eight-year-old Monroe, president of the United States, stopped in Trenton. Although the town had grown quite a bit the old Revolutionary—”the last of the cocked hats” as he was called—was moved by his recollections to deliver a stirring address. In it, wrote Ammon, Monroe referred to Trenton “as the site where the hopes of the nation had revived at the ebb tide of the Revolution. Of his wound he said nothing, but the local press adequately reminded the citizens of his heroism.”

Recent Articles

Those Deceitful Sages: Pope Pius VI, Rome, and the American Revolution

Trojan Horse on the Water: The 1782 Attack on Beaufort, North Carolina

This Week on Dispatches: Eric Sterner on How the Story of Samuel Brady’s Rescue of Jane Stoops became a Frontier Legend

Recent Comments

"Trojan Horse on the..."

Great article. Love those events that mattered mightily to participants but often...

"Those Deceitful Sages: Pope..."

Fascinating stuff. We don't always approach the American Revolution in its wider...

"Trojan Horse on the..."

Scott....thank you, and indeed Dr Crow's work was a great help for...