Did Thomas Paine actively write against the American cause after emigrating from England in late 1774 and only opportunistically pretend to support the cause? When Paine was nominated for a Congressional position in April 1777, did delegate John Witherspoon hurl those accusations against Paine?[1]

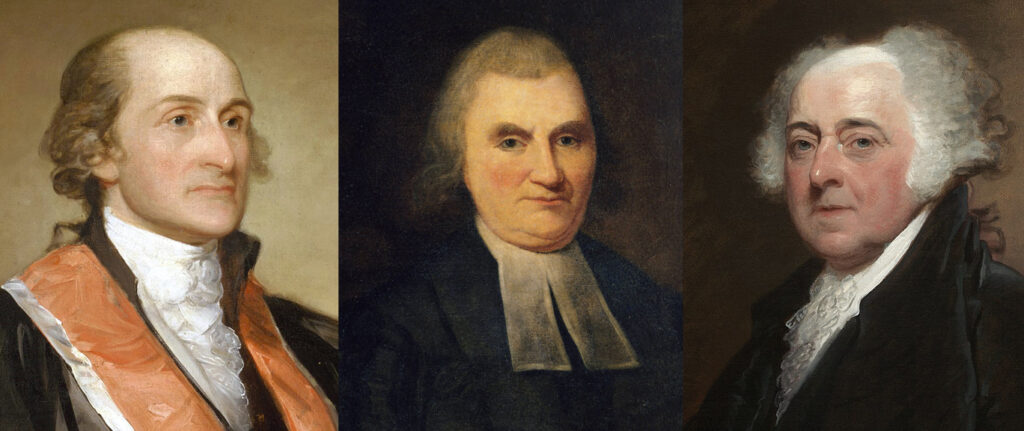

As other delegates were undoubtedly well aware, Witherspoon knew Paine personally. In 1775, while Paine edited Robert Aitken’s The Pennsylvania Magazine, Aitken was Witherspoon’s “compatriot and protégé” and Witherspoon regularly contributed to and co-owned the magazine.[2] Had the prominent and highly respected Reverend Witherspoon called Paine a secret Tory who only pretended to be a patriot on the floor of Congress in 1777, that could have devastated a reputation that, though ascendant after Common Sense and “The Times That Try Men’s Souls,” was fragile given how little was known about Paine’s pre-America life.[3]

Whether Witherspoon, who died in 1794, made those accusations is grounded on the Autobiography that John Adams wrote between 1802 to 1807.[4] Adams claimed that, after he nominated Paine as Secretary to the Foreign Affairs Committee, Witherspoon objected that “he knew the Man and his Communications,” that when Paine “first came over” from England “he was on the other Side and had written pieces against the American Cause,” and that Paine “had afterwards been employed by his Friend Robert Aitkin,” and only “turned about” upon “finding the Tide of Popularity run rapidly” the other way. Adams claimed he was “surprized” by Witherspoon’s accusations and his “Earnestness,” that Daniel Roberdeau “spoke in [Paine’s] favour,” and that Paine’s nomination was approved after no one confirmed the accusations. But, Adams added without explanation, “the truth of it has since been sufficiently established.”[5] During the five year period that Adams wrote his Autobiography, his rage against Paine was incandescent.[6]

John Jay’s son found a similar account among Jay’s papers after his 1829 death. Jay, like John Adams, reviled Paine with increasing passion as time went on.[7] Paine gave Jay plenty of cause, accusing him publicly of disloyalty and treason.[8]

The Jay account referenced, among other things, accusations by Witherspoon although Jay, a delegate, had not attended Congress during 1777.[9] Jay asserted Paine’s “attachment to the American cause became suspected” while he edited the Pennsylvania Magazine, and that Paine had “struck out several passages in papers composed by Dr. Witherspoon, as being too free.” The Jay account then asserted that Paine “became attached to some leading men who were most zealous for American independence” and, while Paine served as Secretary and “General Washington was retreating before the enemy in Jersey, and the minds of many were filled with apprehensions, [Paine] was again so suspected as that Congress became uneasy lest the committee’s papers in his custody should fall into the enemy’s hands, and took their measures accordingly” with only the “success at Trenton” giving “new courage to Paine.”[10]

Some scholars assume that Witherspoon made accusations against Paine.[11] Others assert that Paine’s loyalty to the cause actually was suspect.[12] Some express discomfort.[13] Others minimize the situation through omission.[14] Still others are dismissive.[15] No scholar has conducted analysis with sufficient vigor.[16] Shying away from proper analysis is understandable since proving a negative is challenging. Evaluating relevant evidence, however, it defies common sense to conclude that Witherspoon made accusations against Paine much less that Paine actually wrote against the cause, opportunistically pretended patriotism, or displayed disloyalty to America.

The Adams and Jay accounts start crumbling on cursory examination. Adams had Paine writing “pieces against the American cause” before he was Aitken’s editor. No one else ever suggested that Paine wrote anything in America before becoming Aitken’s editor.[17] Jay had Washington retreating through New Jersey after Paine was appointed Secretary in 1777 and the Battle of Trenton occurring after Congress had taken “measures” against Paine in 1779. Both events occurred in 1776 before Paine’s appointment.[18] Adams had Witherspoon making accusations short in length, details, spice and humor. Witherspoon, when disparaging Tories, used florid, descriptive, humorous and devastating language.[19] Concerns about Paine during the Deane affair were never, as Jay knew, about his loyalty much less risk of his disclosing documents to the enemy. Jay and others instead criticized Paine because, in attacking their friend Silas Deane for prioritizing personal profit over patriotism, Paine publicized the open secret that France started assisting America before their alliance.[20]

Their shared loathing of Paine made Adams and Jay suspect messengers. Deeper analysis is needed to prove a negative, i.e., that Witherspoon did not make those accusations.

On April 17, 1777, when Witherspoon supposedly made accusations opposing Paine’s nomination, at least thirty-five delegates attended Congress.[21] From April 17 to May 16, 1777, none of the 119 letters authored by those thirty-five delegates mentioned Paine or Witherspoon, much less anything regarding Paine’s patriotism although many letters discussed details and tidbits about current activities in Congress. No letter hinted at the presumably shocking news that the author of Common Sense and American Crisis No. 1 was accused—by a respected clergymen claiming first-hand knowledge—of being a secret Tory who wrote articles opposed to the American cause and who opportunistically pretended to support the cause.[22]

Was John Adams surprised by Witherspoon’s accusations and “Earnestness” with which he made them?[23] If so, why were Paine, Witherspoon and the accusations unmentioned in his twenty-four letters—thirteen to Abigail Adams from whom he rarely kept secrets—during that subsequent month?[24]

Why were Paine, Witherspoon and the accusations unmentioned in the fourteen letters sent by six friends of Paine who attended as delegates on April 17, 1777?[25] Paine was plainly unaware of any critique associated with his appointment when he wrote Franklin in June 1777 about his “pleasure” and “honor” in being appointed.[26] None of those six friends, including Roberdeau who supposedly vocalized objections, thought to mention the accusations to Paine?

On April 19, 1777—two days after Paine’s appointment—his American Crisis No. 3 proposed vigorous measures for eliminating American Tories.[27] Secrecy of Congressional proceedings was, as now, a speed bump for leakers.[28] Had Witherspoon, two days earlier, accused Paine of secret Toryism, would no one have noted the irony?[29] Letters from attending delegates that discussed Toryism did not mention accusations that Paine was a Tory.[30]

Paine’s character assassins, Chalmers and Cobbett in the 1790s and Cheetham in the 1800s, would have feasted on any accusations if made but none of them even hinted at any accusations.[31] By 1797, when Cobbett (“Peter Porcupine”) published his book attacking Paine, nine delegates present on April 17, 1777 were active Federalists.[32] Cobbett publicly assaulted Paine, anathema amongst Federalists for authoring his Letter to Washington and Age of Reason, with frequency in 1794, 1795 and 1796.[33] Ample time and multiple sources were available, by 1797, to quietly provide Cobbett with porcupine quills poisoned by Witherspoon—had Witherspoon made the accusations.

Conspicuously, no dog barked, even decades after Paine’s appointment. More telling, what we know about Witherspoon refutes the Adams and Jay accounts. Witherspoon’s writings disclose no hint that he thought Paine disloyal.[34]

If anything, it was Aitken who, nostalgic for England, sought to prevent contents of The Pennsylvania Magazine from supporting the cause.[35] By all accounts, Paine and Witherspoon creatively evaded Aitken constraints—like moviemakers later evading Hays Code constraints—even before the transformative battles of April 1775 started the war.[36]

Benjamin Rush recalled being pleased, when first meeting Paine in February 1775, to learn that Paine and he agreed that independence was essential to winning the war. And, when anonymous accusations of Toryism appeared in newspapers in 1779 during the Deane affair, Paine’s friend Charles Willson Peale “declar[ed] from personal knowledge that Paine had ‘done more for our common cause than the world, who had only seen his publications, could know.’”[37]

But assume, contrary to the evidence, that a far more compliant Paine scrupulously heeded the Aitken constraints by maintaining political neutrality in the magazine’s content. Would Witherspoon have concluded, from that compliance, that Paine actively wrote against the American cause and was a secret Tory?

Actually, Paine was likely far ahead of Witherspoon in their respective views on the cause. In May 1775—after war started—Witherspoon wrote a letter consistent with “the widespread ambivalence of his time” of wanting “to be loyal” to Britain while unwilling to “accept the condensation” and other insults with which Britain treated the colonies.[38]

Common Sense, published in January 1776, apparently persuaded Witherspoon to abandon prior hopes of reconciliation and support independence. Publicly praising Paine’s arguments about independence, Witherspoon criticized Paine’s religious views (like dismissing original sin) and his grammar and prose style but never expressed the slightest doubt about Paine’s loyalty.[39]

In fact, Witherspoon so firmly supported Common Sense that he publicly wished that it had been serialized in newspapers since, in his view, it would have commanded an even wider readership.[40] By April 1776, Witherspoon lobbied New Jersey officials “strongly for a complete break with England.”[41]

The clincher, if needed, is that Witherspoon threw his considerable rhetorical weight unequivocally in favor of Paine, while blasting his opponents, at the precise time and place—May 13, 1776 in a Philadelphia newspaper article—that Paine and his radical friends needed all the help they could get.[42] Refusing to accept the results of an extraordinarily fair May 1, 1776 election through which reconciliation advocates retained control of Pennsylvania government, Paine and his colleagues sought to overthrow that government and replace it with one supporting independence.[43] On May 13, with the pot boiling and the outcome uncertain, Witherspoon could well have remained silent. Instead, undoubtedly alienating friends and risking a treason trial should the British capture him, he jumped in with both feet.[44] Once convinced by Common Sense, Witherspoon cast aside temptations of reconciliation, embraced independence, and skewered lingering advocates of reconciliation both in his May 13 article and in a speech to Congress as he voted for independence.[45]

When all available evidence is considered, is it rational to conclude that Witherspoon made the accusations against Paine attributed to him in the Adams and Jay accounts?

Before answering that question, Paine left a separate clue for consideration. In October 1783, Paine related his belief that two or three Congressional delegates told the late John Laurens in December 1780, as he requested Paine’s appointment to assist on his French mission, that they doubted Paine’s principles because he came to the cause “late.” Narrowing the suspects, Paine said those who talked to Laurens were “out” of Congress by October 1783 and included a delegate upset that Paine, through Common Sense, went beyond him in literary reputation.[46]

Thirty-one delegates including Witherspoon attended Congress in December 1780 and were “out” of Congress in October 1783.[47] The “literary reputation” clue superficially points towards Witherspoon.[48] But his public praise for Common Sense and barraging of Paine’s foes with rhetorical artillery in his May 13, 1776 article—that Paine no doubt appreciated—should exclude Witherspoon as a suspect.

Beyond the lack of evidence corroborating the Adams and Jay accounts, how could anyone credibly accuse Paine in April 1777 of opportunistically pretending to be a patriot? Paine was the polar opposite of an opportunist, struggling financially because he refused profits from his writings, keeping his head above water only through sporadic and minimalist financial assistance from friends and appreciative legislators.[49]

The Adams and Jay accounts defy common sense. Did they consciously concoct those accounts or, late in life, succumb to severely faulty memories that gratified their respective deep disgust for Paine? Since Jay did not attend in 1777, we can charitably assume that he absorbed gossip which solidified, with resentment of Paine curdling over time, into faulty memory. Since Adams participated in Paine’s appointment, mustering a charitable interpretation is more challenging. Perhaps, despite his multiple prior interactions with Witherspoon, he misunderstood Witherspoon’s thick Scottish brogue?[50]

Their motives are irrelevant. Future biographies of those implicated—Paine, Witherspoon, Adams, Jay and other Founders—should affirmatively confirm that the Adams and Jay accounts are baseless. Not a whiff of reliable evidence suggests either that Witherspoon made accusations against Paine in April 1777, that Paine opposed the American cause, or that Paine just pretended to be the patriot he clearly was.

[1] John Adams, Diary and Autobiography of John Adams, ed. L. H. Butterfield (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1962), 3:334; William Jay, The Life of John Jay with Selections from his Correspondence (New York: J & J Harper, 1833), 1:97.

[2] Lyon Richardson, A History of Early American Magazines, 1741-1789 (New York: T. Nelson and Sons, 1931), 176-177, 179, 183-184.

[3] John Keane, Tom Paine: A Political Life (New York: Little, Brown & Co, 1995), xvii & 23 (Paine “did all he could to keep his private life private” and “closely guarded his early private life”); David Freeman Hawke, Paine (New York: W. W. Norton, 1974), 403 (Paine was “an exceedingly private man”).

[4] Jeffry H. Morrison, John Witherspoon and the Founding of the American Republic (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2005), 2 (Witherspoon died in 1794). Adams wrote his Autobiography from 1802 to 1807, leaving a “chaotic and jumbled” mess. John Ferling, John Adams: A Life (New York: Henry Holt & Co, 1992), 421-423. Adams inserted his account regarding Paine’s appointment in Spring 1777 amongst Spring 1776 events in what he titled “Part One: To October 1776.” Adams, Diary and Autobiography, 3:253, 330-337. That odd placement and the lack of diary entries between February and September 1777 (Adams, Diary and Autobiography, 2:261-262) suggest that he consulted no documents in creating this account.

[5] Adams, Diary and Autobiography, 3:334 (“I nominated Thomas Paine, supposing him a ready Writer and an industrious Man. Dr. Witherspoon the President of New Jersey Colledge and then a Delegate from that State rose and objected to it, with an Earnestness that surprized me. The Dr. said he would give his reasons; he knew the Man and his Communications: When he first came over, he was on the other Side and had written pieces against the American Cause: that he had afterwards been employed by his Friend Robert Aitkin, and finding the Tide of Popularity run pretty strong rapidly, he had turned about: that he was very intemperate and could not write untill he had quickened his Thoughts with large draughts of Rum and Water: that he was in short a bad Character and not fit to be placed in such a Situation. – General Roberdeau spoke in his favour: no one confirmed Witherspoons Account, though the truth of it has since been sufficiently established.” (Strikeouts in original.))

[6] In a 1796 diary entry, Adams merely called Paine a “blackguard” (John Adams, The Works of John Adams, ed. C. Adams (Boston: Little & Brown, 1851), 3:421. Within his Autobiography, he became more descriptive, characterizing Paine as “that insolent blasphemer of things sacred, and transcendent libeller of all that is good.” Adams, Works, 3:93. In 1805, he called Paine “a mongrel between Pigg and Puppy, begotten by a wild Boar on a Bitch Wolf,” and asserted that “never before in any Age of the World was suffered by the Poltroonery of mankind, to run through Such a Career of Mischief” as Paine. Adams to Benjamin Waterhouse, October 29, 1805, in John Adams, Statesman and Friend: Correspondence of John Adams with Benjamin Waterhouse, 1784-1822, ed. C. Ford (Boston: Little & Brown, 1927), 31. The fury never diminished. E.g. Adams to Jefferson, June 22, 1819, Adams, Works, 10:380-381 (“What a poor, ignorant, malicious, short-sighted, crapulous mass is Tom Paine’s ‘Common Sense,’”).

[7] Jay, The Life of John Jay, 1:97 (Paine’s “attachment to the American cause” while Aitken’s editor “became suspected. He struck out several passages in papers composed by Dr. Witherspoon, as being too free. He afterward became attached to some leading men who were most zealous for American independence … when General Washington was retreating before the enemy in Jersey, and the minds of many were filled with apprehensions, he was again so suspected as that Congress became uneasy lest the committee’s papers in his custody should fall into the enemy’s hands, and took their measures accordingly. The success at Trenton gave things a new aspect, and new courage to Paine.”) Jay’s son found the Jay account amongst fragmentary notations about Jay’s Spain mission. Jay, The Life of John Jay, 1:95. Nothing in those notations convey when Jay wrote them. Ibid., 1:95-101. Originals of the notations and the Jay account may no longer exist. The Selected Papers of John Jay, ed. E. Nuxoll (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2010 to 2022), 1:xlv-liii (editor relating that many Jay papers are unlocated and presumed lost). In compiling documents regarding the Spain mission, Richard Morris included nothing from those notations. Compare Jay, The Life of John Jay, 1:95-101, with John Jay: The Making of a Revolutionary: Unpublished Papers, 1745-1780, ed. R. Morris (New York: Harper & Row, 1975), 649-835 and John Jay: The Winning of the Peace: Unpublished Papers, 1780-1784, ed. R. Morris (New York: Harper & Row, 1980), 25-136. More general compilations of Jay’s papers have not included the Jay account; see The Correspondence and Public Papers of John Jay, ed. H. Johnston (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1890 to 1893) and The Selected Papers of John Jay.

[8] Paine publicly challenged Jay’s loyalty during the Deane affair. “Messrs. Deane, Jay and Gerard” [1779], The Complete Writings of Thomas Paine, ed. P. Foner (New York: The Citadel Press, 1945), 2:181-186. In the 1790s, he accused Jay of disloyalty and treason. (“Observations on Jay’s Treaty,” [1795], The Complete Writings of Thomas Paine, 568-570; Paine, “Letter to George Washington,” [1796], The Complete Writings of Thomas Paine, 696, 707-708, 715, 722.

[9] Jay, The Life of John Jay, 1:95. Jay did not attend Congress during 1777. Letters of Delegates to Congress 1774 to 1789, ed. P. Smith (Washington, DC: Library of Congress, 1976-2000), 6:xix. He was instead occupied in New York. The Selected Papers of John Jay, 1:350-500.

[10] Jay himself “hoped for reconciliation with England until about 1778.” John Eidsmoe, Christianity and the Constitution: The Faith of Our Founding Fathers (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 1995), 163. Jay recalled in 1821 that he had never heard “any American, of any class, or of any Description, express a wish for the Independence of the colonies” until after “the second Petition of congress (in 1775).” Jay to Adams, January 21, 1821, in Jeremiah Colburn, American Independence: Did the Colonists Desire It? (Boston: David Clapp & Son, 1876), 4. This apparently referenced the “Olive Branch” Petition adopted on July 6, 1775. James H. Hudson, A Decent Respect to the Opinions of Mankind (Washington, DC: Library of Congress, 1975), 90.

[11] Hawke, Paine, 67, 114; David Freeman Hawke, Honorable Treason: The Declaration of Independence and the Men who Signed It (New York: Viking, 1976), 134 (Witherspoon “hated” Paine); Frank Smith, Thomas Paine: Liberator (New York: Frederick A. Stokes Co., 1945), 40-41; Morrison, John Witherspoon, 34. Hawke assumed Witherspoon made the accusations partly because Paine said, “parsons were always mischievous fellows when they turned politicians.” Hawke, Paine, 67. But Paine made that remark decades later after a parson was elected an M.P. in England. Moncure Daniel Conway, The Life of Thomas Paine (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1892), 2:302. And Paine was plainly unaware in 1777 of any critiques associated with his appointment. Paine to Franklin, June 20, 1777, The Complete Writings of Thomas Paine, 2:1132.

[12] Jack Fruchtman, Jr., Thomas Paine: Apostle of Freedom (New York: Four Walls Eight Windows, 1994), 10, 39, 95-96 (assuming accusations were made and concluding, by misinterpreting Paine, that he was “ambivalent”); Keane, Tom Paine, 155, 206, 549n87 (assuming accusations were made, concluding they were untrue, assuming the Jay account was true, and asserting Paine “consistently concealed his early literary activities”); ibid., 103 (assuming Paine removed language from a Witherspoon article as “too free” and stating without cited support that Aitken argued that Paine should reinsert the language, although all available evidence indicates that Aitken, not Paine, sought to exclude political content).

[13] Conway, The Life of Thomas Paine, 1:92 (speculating that Witherspoon made accusations based on Paine’s anti-slavery positions); David A. Wilson, Paine and Cobbett: A Transatlantic Connection (Kingston, Quebec: McGill-Queens University Press, 1988), 37n10 (same).

[14] W. E. Woodward, Tom Paine: America’s Godfather 1737-1809 (New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., 1945), 96 (asserting Witherspoon admitted his accusations were “based entirely on hearsay” although the Adams account had Witherspoon claiming personal knowledge); Harvey J. Kaye, Thomas Paine and the Promise of America (New York: Hill and Wang, 2006), 35-36 (ignoring disloyalty accusations).

[15] Robin McKown, Thomas Paine (New York, G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1962), 59 (assuming Witherspoon made accusations while asserting Paine was never “a Tory, or sympathized with Tory thinking, in his life”); David Powell, Tom Paine: The Greatest Exile (London: Hutchinson, 1989), 95-96; Howard Fast, Citizen Tom Paine (New York: The World Publishing Co., 1943), 159-161.

[16] Alfred Owen Aldridge, Man of Reason: The Life of Thomas Paine (Philadelphia: J. P. Lippincott Co., 1959), 52-53 (though flawed, the best analysis); Alfred Owen Aldridge, Thomas Paine’s American Ideology (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1984), 36-37, 293-294, nn1 and 9.

[17] Adams, Diary and Autobiography, 3:334. Efforts to identify all Paine writings preceding Common Sense disclosed nothing written in America before his Aitken editorship. Aldridge, Thomas Paine’s American Ideology, 27-28, 286-291 (“Appendix: Paine’s Publications Before Common Sense”). No biographer suggested that he had. Francis Oldys [George Chalmers], The Life of Thomas Pain (London: John Stockdale, 1791), 39; William Cobbett, The Life of Thomas Paine, Interspersed with Remarks and Reflections by Peter Porcupine (London: J. Wright, 1797), 28; James Cheetham, The Life of Thomas Paine (London: A. Maxwell, 1817), 21; Thomas Clio Rickman, The Life of Thomas Paine (London: Thomas Clio Rickman, 1819), 48; W. T. Sherwin, Memoirs of the Life of Thomas Paine (London: R. Carlile, 1819), 22-23; Gilbert Vale, The Life of Thomas Paine with Critical and Explanatory Observations on His Writings (Boston: G. P. Mendum, 1876), 30-31; Calvin Blanchard, The Life of Thomas Paine (New York: Calvin Blanchard, 1860), 12; Conway, The Life of Thomas Paine, 1:40-42; Aldridge, Man of Reason, 29; Hawke, Paine, 26-28; Eric Foner, Tom Paine and Revolutionary America (London: Oxford University Press, 1976), 72; A. J. Ayer, Thomas Paine (New York: Atheneum, 1988), 7-8; Keane, Tom Paine, 91-93; Scott Liell, 46 pages: Thomas Paine, Common Sense, and the Turning Point to American Independence (New York: MJF Books, 2003), 49-50; Craig Nelson, Thomas Paine: Enlightenment, Revolution, and Modern Nations (New York: Viking, 2006), 50-52; Kaye, Thomas Paine and the Promise of America, 34.

[18] Jay, The Life of John Jay, 1:97; Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774 to 1787, ed. C. Ford (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1907), 7:273-274; Aldridge, Man of Reason, 52 (“Paine was not made secretary until after Washington’s retreat, and Jay’s insinuation is patently false”). The glaring errors in the Jay account about time sequences that Jay certainly would not have made closer to 1777 suggest it was written much later in Jay’s life.

[19] David Walker Woods, John Witherspoon (New York: Fleming H. Revell Co., 1906), 242-245.

[20] Keane, Tom Paine, 174-180.

[21] Journals of the Continental Congress, 7:273-274. Analysis is restricted to thirty-five delegates confirmed as attendees on April 17, 1777: Roger Sherman, Oliver Wolcott, James Sykes, Nathan Brownson, George Walton, Benjamin Rumsey, William Smith, John Adams (JA), Samuel Adams (SA), Elbridge Gerry, John Hancock, James Lovell, Matthew Thornton, William Whipple, Jonathan Elmer, Jonathan Dickinson Sergeant, John Witherspoon, James Duane, William Duer, Francis Lewis, Philip Livingston, Lewis Morris (LM), Philip Schuyler, Thomas Burke, George Clymer, Robert Morris (RM), Daniel Roberdeau, Jonathan Bayard Smith, James Wilson, William Ellery, Thomas Heyward, Arthur Middleton, Benjamin Harrison, Francis Lightfoot Lee (FLL), Richard Henry Lee (RHL), and Mann Page. Letters of Delegates, 6:xv-xxii; Letters of Members of Congress, ed. E. Burnett (Washington DC: Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1923), 2:xxxix to lxxii. No relevant letter is omitted since nothing sent during the subsequent month by any delegate or by any Committee mentioned Paine, Witherspoon, or the accusations. Letters of Delegates, 6:599-692, 7:3-88.

[22] The thirty-five Delegates confirmed as attendees on April 17, 1777, sent 119 letters during the subsequent month. Letters of Delegates, 6:599-601 (4/17 SA), 6:601-604 (4/17 Duer), 6:604 (4/17 Lewis), 6:604-606 (4/17 Rumsey), 6:606-607 (4/17 Sherman), 6:607-610 (4/17 Wolcott), 6:610 (4/18 Hancock), 6:610-611 (4/18 Hancock), 6:613-616 (4/18 Walton), 6:616 (4/19 JA), 6:616-618 (4/19 Duane), 6:618-619 (4/19 Gerry), 6:619 (4/19 Hancock), 6:622 (4/19 LM), 6:624-625 (4/19 Whipple), 6:625-626 (4/19 Whipple), 6:626-627 (4/20 Hancock), 6:627 (4/20 Hancock), 6:627-629 (4/20 RHL), 6:631 (4/21 Page), 6:632-633 (4/22 JA), 6:633 (4/22 RHL), 6:634 (4/22 Page), 6:635 (4/22 Schuyler), 6:636 (4/23 JA), 6:637-638 (4/23 SA), 6:639 (4/23 (Hancock), 6:641-642 (4/23 Sherman), 6:643-644 (4/23 Whipple), 6:644-645 (4/23 Wolcott), 6:645-646 (4/23 Wolcott), 6:646-647 (4/24 Ellery), 6:647-648 (4/24 Lewis), 6:648 (4/24 Schuyler), 6:650 (4/24 Wolcott), 6:650-651 (4/25 Hancock), 6:651-652 (4/25 RM), 6:652-653 (4/25 RM), 6:653-654 (4/26 JA), 6:654-655 (4/26 Hancock), 6:659-660 (4/26 Schuyler), 6:660 (4/26 Schuyler) 6:660-662 (4/27 JA), 6:662-663 (4/27 JA), 6:663 (4/27 JA), 6:664-665 (4/27 JA), 6:665 (4/27 Schuyler), 6:665-666 (4/27 Whipple), 6:666-667 (4/28 JA), 6:667-668 (4/28 JA), 6:669-670 (4/29 JA), 6:670 (4/29 JA), 6:671-674 (4/29 Burke), 6:674-675 (4/29 Hancock), 6:675 (4/29 Hancock), 6:675-676 (4/29 RHL), 6:676-677 (4/29 RHL), 6:687 (4/30 JA), 6:688 (4/30 Burke), 6:688 (4/30 Hancock), 6:688-689 (4/30 Schuyler), 6:689-690 (4/30 Sherman), 6:690-691 (4/30 Whipple), 6:681-692 (4/30 Wolcott), 7:3-4 (5/1 Elmer), 7:4-5 (5/1 Lovell), 7:7-9 (5/1 RM), 7:9 (5/1 Roberdeau), 7:10 (5/1 Rumsey), 7:11-12 (5/1 Walton), 7:12 (5/2 JA), 7:13 (5/2 JA), 7:13-14 (5/2 Burke), 7:17 (5/2 Duane), 7:17-18 (5/2 Hancock), 7:21-22 (5/3 JA), 7:22 (5/3 Hancock), 7:22-23 (5/3 FLL), 7:23-24 (5/3 Rumsey), 7:24-25 (5/3 Whipple), 7:25 (5/4 JA), 7:27 (5/5 Hancock), 7:28 (5/6 JA), 7:28-29 (5/6 JA), 7:29-30 (5/6 JA), 7:30 (5/6 JA), 7:31 (5/6 Duane), 7:31-32 (5/6 Duer), 7:32-33 (5/6 RHL), 7:33-34 (5/6 Page), 7:43 (5/7 JA), 7:44-45 (5/7 Schuyler), 7:45-46 (5/7 Whipple), 7:46-50 (5/8 Ellery), 7:50 (5/9 Ellery), 7:57-58 (5/10 JA), 7:59-60 (5/10 JA), 7:61-62 (5/10 Hancock), 7:62-63 (5/10 Hancock), 7:63-64 (5/10 RHL), 7:64-65 (5/10 RM), 7:65 (5/10 Schuyler), 7:66-68 (5/10 Whipple), 7:69-70 (5/11 Burke), 7:70-71 (5/12 SA), 7:72 (5/12 Lovell), 7:72-74 (5/13 Gerry), 7:74-75 (5/13 Hancock), 7:75-76 (5/13 RHL), 7:76-77 (5/13 RHL), 7:78 (5/13 Elmer), 7:80-81 (5/13 Sherman), 7:81 (5/14 JA), 7:81-83 (5/14 Sherman), 7:83-84 (5/14 JA) 7:84 (5/13 Hancock), 7:84-85 (5/15 Schuyler), 7:87-88 (5/16 Sherman).

[23] Adams, Diary and Autobiography, 3:334.

[24] Letters of Delegates, 6:616 (4/19 JA to AA), 6:632-633 (4/22 JA to AA), 6:636 (4/23 JA to AA), 6:653-654 (4/26 JA to AA), 6:660-662 (4/27 JA to AA), 6:662-663 (4/27 JA), 6:663 (4/27 JA), 6:664-665 (4/27 JA), 6:666-667 (4/28 JA to AA), 6:667-668 (4/28 JA), 6:669-670 (4/29 JA to AA), 6:670 (4/29 JA), 6:687 (4/30 JA to AA), 7:12 (5/2 JA to AA), 7:13 (5/2 JA), 7:21-22 (5/3 JA), 7:25 (5/4 JA to AA), 7:28 (5/6 JA to AA), 7:28-29 (5/6 JA), 7:29-30 (5/6 JA), 7:30 (5/6 JA), 7:43 (5/7 JA to AA), 7:57-58 (5/10 JA to AA), 7:59-60 (5/10 JA), 7:81 (5/14 JA to AA), 7:83-84 (5/14 JA to AA).

[25] Richard Henry Lee, James Duane, Lewis Morris, George Clymer, Samuel Adams, and Daniel Roberdeau were Paine friends. Keane, Tom Paine, 155, 175, 181 & 221 (RHL); Keane, Tom Paine, 251 (Duane); Keane, Tom Paine, 251-252, 269 (LM); Keane, Tom Paine, 259 & 275 (Clymer); Keane, Tom Paine, 475-478 (SA); Woodward, Thomas Paine, 117 (Roberdeau). Those friends wrote fourteen letters during the subsequent month. Letters of Delegates, 6:599-601 (4/17 SA), 6:616-618 (4/19 Duane), 6:622 (4/19 LM), 6:627-629 (4/20 RHL), 6:633 (4/22 RHL), 6:675-676 (4/29 RHL), 6:676-677 (4/29 RHL), 7:9 (5/1 Roberdeau), 7:17 (5/2 Duane), 7:31 (5/6 Duane), 7:32-33 (5/6 RHL), 7:63-64 (5/10 RHL), 7:70-71 (5/12 SA), 7:75-76 (5/13 RHL), 7:76-77 (5/13 RHL).

[26] Paine to Franklin, June 20, 1777, The Complete Writings of Thomas Paine, 2:1132 (“I have … the pleasure of acquainting you of my being appointed Secretary to the Committee of foreign affairs” and “conceive the honor to be the greater as the appointment was only unsolicited on my part but made unknown to me”).

[27] Aldridge, Man of Reason, 52; Paine, American Crisis No. 3 [April 19, 1777], The Complete Writings of Thomas Paine, 1:73-101; Conway, The Life of Thomas Paine, 1:91-92.

[28] Thomas Fleming, The Perils of Peace: America’s Struggle for Survival After Yorktown (New York: HarperCollins, 2007), 61 (“proceedings of Congress were theoretically secret” but all of “Philadelphia gossiped about what was said and done within Congress’s supposedly inviolable chamber”).

[29] Paine’s writings were subjected to public criticism in 1777 in Philadelphia newspapers. E.g., Phocian, “To Common Sense and De Wit,” Dunlap’s Pennsylvania Packet and General Advertiser, March 25, 1777, 3, cl. 2, https://www.newspapers.com/image/1034014731/.

[30] Letters of Delegates, 6:604-606 (4/17 Rumsey), 7:46-50 (5/8 Ellery), 7:75-76 (5/13 RHL).

[31] Chalmers related Paine’s appointment while falsely asserting that Franklin said Paine had a “bad character”). Oldys [Chalmers], The Life of Thomas Pain, 53-54. Cobbett related Paine’s appointment while blasting later puffing. Cobbett, The Life of Thomas Paine, 31-34, 94-96. Cobbett also asserted, without evidence, that Paine would have opportunistically written against the American cause had England not fired him as an Excise Officer without hinting that anyone else ever accused Paine of opportunism. Ibid., 18-20. Cheetham never suggested anyone accused Paine of disloyalty. Cheetham, The Life of Paine, 1-87. Cheetham noted Paine’s appointment only to criticize later puffing and mentioned Witherspoon only in vote results. Ibid., 34, 42.

[32] Ellis Paxton Oberholtzer, Robert Morris: Patriot and Financier (New York: The MacMillan Co., 1903), 184-185, 219 (RM); Robert G. Ferris, Signers of the Declaration: Historic Places Commemorating the Signing of the Declaration of Independence (Washington, DC: National Park Service, 1974), 35 (JA), 52 (Ellery); Jo Anne McCormick Quatannens, Senators of the United States: A Historical Bibliography (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1995), 247 (Schuyler), 280 (Walton); Chester McArthur Destler, Joshua Coit, American Federalist, 1758-1798 (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1962), 72 (Wilson); Robert F. Jones, “The King of the Alley” William Duer, Politician, Entrepeneur and Speculator, 1768-1799 (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1992), 111-113 (Duer); Charles Oscar Paullin, The First Elections Under the Constitution (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1900), 21 (Elmer); John A. Munroe, Federalist Delaware, 1775-1815 (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1954) 178-179, 265-266, 271 (Sykes). Jay was also a strong Federalist. Eidsmoe, Christianity and the Constitution, 77-78. Cobbett publicly and regularly blasted Paine from August 1794 until he wrote his 1797 book. E.g., William Cobbett, “Observations on Priestley’s Emigration” [1794], Porcupine’s Works (London: Cobbett & Warren, 1801), 1:154, 163, 168-170 & 177; Cobbett, “A Bone to Gnaw” [1795], ibid., 2:43, 113, 147, 343, 351; Cobbett, “Bloody Buoy” [1796], ibid., 3:181, 243; Cobbett, “The Scare-Crow Etc.” [1796], ibid., 4:14-16, 49. Cobbett’s voluminous writings, collected into twelve volumes (Porcupine’s Works), while supporting the Federalists mentioned Witherspoon only as a Declaration signer (Cobbett, “A Summary View of the Politics of the United States,” ibid., 1:36).

[33] Paine “suffered furious Federalist counterblast” after his Letter to Washington with “many Federalists consider[ing] the wooden-toothed president as sacred as Jesus Christ.” Keane, Tom Paine, 432. “To Federalists, … The Age of Reason made him the Antichrist.” Kaye, Thomas Paine and the Promise of America, 109.

[34] Woods, John Witherspoon, 205-207 (Witherspoon acknowledged the merits of Common Sense while criticizing “the style of it” and, “when an attack was made upon it, … took up his caustic pen to defend ‘Common Sense’” as the “‘first public declaration in favour of independence’”); Aldridge, Man of Reason, 52-53 (“Witherspoon’s own writings give no account of” the alleged episode related by Adams, “the only authority for it being the autobiography of Adams”).

[35] The February 1775 issue explained that, as “it is our design to keep a peaceable path, we cannot admit R.W.’s and M.N.’s political pieces.” The Pennsylvania Magazine, or American Monthly Museum for February 1775, Issue 2, (February 1775), 98. Assumptions that the Jay account correctly charged Paine with rejecting Witherspoon articles as “too free” may rely on this thin reed. Hawke, Paine, 32 (“R.W.” referenced Reverend John Witherspoon); Varnum Lansing Collins, President Witherspoon: A Biography (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1925), 25-26. But the magazine used “J.W.” – not “R.W.” – in referencing Witherspoon when not using pseudonyms (Richardson, A History of Early American Magazines, 183-184, n92) and the February 1775 notice reflected Aitken’s policy.

[36] Liell, 46 pages, 49-52; Richardson, A History of Early American Magazines, 178-179 (Aitken tried to favor reconciliation while “Paine, Witherspoon” and others “gave it tongue to speak in defense of Colonial points of view” (italics added)).

[37] Louis Alexander Biddle, A Memorial Containing Travels Through Life or Sundry Incidents in the Life of Dr. Benjamin Rush (Philadelphia: Langraie, 1905), 83-85; Aldridge, Thomas Paine’s American Ideology, 36-37. Paine’s published 1775 expressions consistently praised America and criticized England. Wilson, Paine and Cobbett, 35-41.

[38] Martha Lou Lemmon Stohlman, John Witherspoon: Parson, Politician, Patriot (Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1976), 105.

[39] Gideon Mailer, John Witherspoon’s American Revolution (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2017), 253-254; Morrison, John Witherspoon, 60 (“in a newspaper article defending Paine’s Common Sense, [Witherspoon] came down squarely on the side of the political instincts of the common people, who were behind independence. Paine’s arguments for American self-government were, to Witherspoon’s mind, irrefutable. Common Sense may have ‘wanted polish’ in places, he observed, and ‘sometimes failed in grammar, but never in perspicuity.’”); Woods, John Witherspoon, 206-207. A Witherspoon biographer concluded that the “only printed comments on Paine coming from Dr. Witherspoon’s pen are a thrust at a vulgarism in Common Sense, a criticism of a reference in the same production to the doctrine of original sin, … and an allusion in his essay signed ‘Aristides’ defending the purpose, though not the style, of Common Sense against Plain Truth, Cato’s Letters and similar contemporary productions.” Collins, President Witherspoon: A Biography, 25-26.

[40] Jean Folkerts, Dwight L. Teeter and Edward Caudilll, Voices of a Nation: A History of Mass Media in the United States (Boston: Pearson/Allyn & Bacon, 5th ed. 2009), 36, 58, text and n64.

[41] Stohlman, John Witherspoon, 108-109.

[42] The force with which Witherspoon supported Paine and dispatched his opponents in that article is hard to overstate. John Witherspoon, The Works of The Rev. John Witherspoon (Philadelphia: William W. Woodward, 2nd ed. revised & corrected, 1802) 4:309-316 (full article); Aristides, “To the Printer of the Pennsylvania Packet,” Dunlap’s Pennsylvania Packet and General Advertiser, May 13, 1776), 1, 4 (full article as originally published).

[43] Matthew Stewart, Nature’s God: The Heretical Origins of the American Revolution (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 2014), 19 (after reconciliation advocates prevailed in the May 1, 1776 election, Paine and others engineered “a Bolshevik-style coup d’etat that replaced the legitimately elected government of the [Pennsylvania] province with a pro-independence faction”); William Hogeland, Declaration: The Nine Tumultuous Weeks When America Became Independent May 1–July 4, 1776 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010), 33-34, 48, 78-80; Steven Rosswurm, Arms, Country and Class: The Philadelphia Militia and “Lower Sort” During the American Revolution, 1775-1783 (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1987), 93-103.

[44] Mailer, John Witherspoon’s American Revolution, 1, 259-262.

[45] Voting for independence, Witherspoon admonished fellow delegates that the country “had been for some time past loud in its demand for the proposed declaration,” and “was not only ripe for the measure but in danger of rotting for the want of it.” Hawke, Honorable Treason, 134.

[46] Congressional resistance to appointing Paine on the French mission caused him to travel at his own expense. Keane, Tom Paine, 204-207. In October 1783, after Laurens died, Paine cryptically described that resistance: “the prejudiced interference of two or three Gentlemen then in Congress but now out, one of whom (who I am sure will never forgive me for publishing Common Sense and going a step beyond him in Literary reputation) went so far as to tell Col. Laurens, that he doubted my principles, for that I did not join in the Cause till it was late.” Paine to a Committee of the Continental Congress, October 1783, The Complete Writings of Thomas Paine, 1234, italics in original.

[47] Only thirty-oen persons confirmed as attending during December 1780 who were “out” in October 1783 are considered: Jesse Root, Oliver Wolcott, Thomas McKean, Nicholas Van Dyke, Richard Howly, George Walton, John Hanson, John Henry, George Plater, Samuel Adams, James Lovell, Artemis Ward, John Sullivan, William Burnet, William Churchill Houston, John Witherspoon, William Floyd, Thomas Burke, Samuel Johnston, Willie Jones, William Sharpe, Samuel J. Atlee, George Clymer, Joseph Montgomery, Henry Wynkoop, Ezekiel Cornell, James Mitchell Varnum, Thomas Bee, John Mathews and Isaac Motte. Letters of Delegates, 16:xvii-xxiv (delegates listed as attending in December 1780) and 21:xvii–xxvi (delegates in October 1783). Seventy-one persons were delegates in December 1780 and “out” in October 1783. Letters of Delegates, 16:xvii–xxiv (delegates in December 1780), and 21:xvii–xxvi (delegates in October 1783).

[48] Keane, Tom Paine, 206 (assuming Paine’s “literary reputation” clue referenced Witherspoon); Hawke, Paine, 114 (same); Aldridge, Man of Reason, 85-86 (same).

[49] Keane, Tom Paine, 109 (noting Paine’s “principled refusal to make a profit on his writings”); Keane, Tom Paine, 342 (Paine “remained adamant that publishing profits ought to be plowed back into political projects”); Keane, Tom Paine, 532 (Paine said he was “‘a volunteer to the world for thirty years without taking profits from anything” he “published in America or in Europe’” and “‘relinquished all profits that those publications might come cheap among the people for whom they were intended’”).

[50] Witherspoon spoke in a “thick Scottish brogue.” Raymond E. Addis, Re-Introducing Our Signers of the Declaration of Independence (Holly, MI: Holly Publishers, 1940), 79.

2 Comments

Enjoyed reading this well-done piece. Although it is indeed very difficult to “prove a negative,” this article presents the kind of exception that sometimes “proves the rule,” by thoroughly debunking a long-repeated story, started by John Adams, that John Witherspoon accused Thomas Paine of being a Tory and opposed his appointment to be Secretary of the Foreign Affairs Committee to the Congress. After exhaustive research, not one iota of evidence was found in support of the tale.

But it is true that the upstart Paine did manage to get under the skin of some of his revolutionary compatriots, especially Adams who in his later years attacked Paine as an undeserving revolutionary figure. And I must say as a long-time student of Paine, I always smile at the thought that the mostly uneducated and unvarnished Paine edited Witherspoon’s writings while both he and the Presbyterian minister were associated with Robert Aitken’s Pennsylvania Magazine. It must have been an interesting relationship between those two.

Very good point about the skills Paine must have brought to editing the erudite submissions of Witherspoon. Perhaps Paine absorbed from interactions with William Lee, editor of the Sussex Weekly Advertiser in Lewes, some editing skills that he carried with him across the Atlantic.