If the gunfire at Lexington and Concord was the “shot heard round the world,” the phrases in the Declaration of Independence were the words read around the world. In the Declaration, Thomas Jefferson declared America an independent nation, rooting his ideas in political theory and justifying them with a list of grievances.[1] After the Declaration was signed, the states drafted their own constitutions to fit the ideals of the fledgling nation. Several state constitutions included Declarations of Rights and implemented the principles of popular sovereignty and natural rights.[2] The state constitution that most radically implemented the ideals of the Declaration belonged to a state that was not yet part of the nation and was, at the time, an independent republic: Vermont.[3] Early Vermonters created a constitution in 1777 that abolished slavery, guaranteed full male suffrage, and allocated funding for education.[4] The creation of Vermont’s constitution was impacted by the revolutionary sentiments of the Declaration, the philosophy of natural rights, and the New England heritage of classical republicanism.

In the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson stated the right to revolution, and he included a long list of grievances against the king to justify rebellion; Vermont followed a similar structure in its constitution. Jefferson wrote that “when [there is] a long train of abuses [from the government] . . . it is their [the people’s] right to throw off such a government.”[5] This declaration was followed by a list of complaints against the king, from dissolving local governments to depriving Americans of fair trials.[6] Vermont’s constitution included a similar declaration of the right to revolution and list of grievances, but these grievances were against New York, not Great Britain.

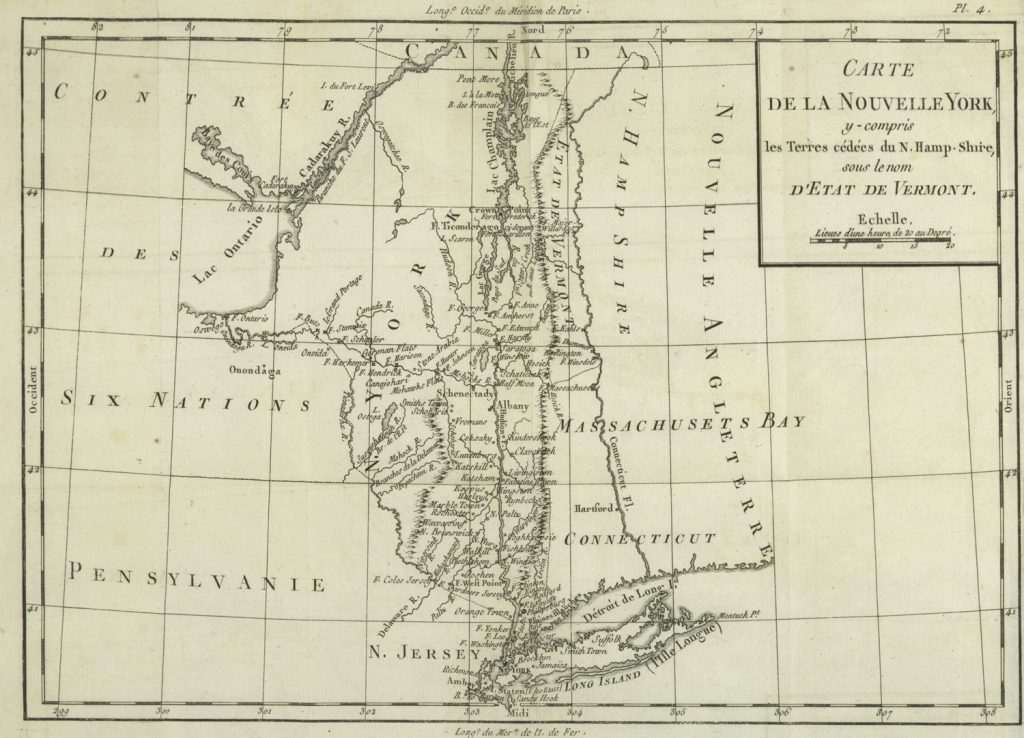

The land that would become Vermont was initially known as the New Hampshire Grants; it was claimed by the governments of New York and New Hampshire.[7] New Hampshire Governor John Wentworth sold thousands of acres in the Grants, enriching himself. In response, Lieutenant Governor Cadwalader Colden of New York regranted the same lands to New Yorkers.[8] This angered the New Hampshire settlers, who as Yankees already disliked the “Yorkers,” so they formed the Green Mountain Boys and fought a guerilla war against New York.[9] Thus, in their new constitution, the Vermonters declared independence from New York. Echoing the Declaration of Independence, they wrote that “whenever those great ends of government are not obtained, the people have a right . . . to change it . . . to promote their safety and happiness.”[10] The authors of the Vermont Constitution then launched into a list of complaints against New York, alleging that the Yorkers waged exorbitant taxes on them, regranted their lands to others, and sent Indigenous Americans and foreign troops to “distress” and drive them out, respectively.[11] By mimicking the style and the format of the Declaration, the Vermonters lent more credence to their arguments and solidified their reasoning for leaving New York.

The revolutionary sentiments of the Declaration were not the only ideals that inspired the Vermonters. The actual provisions of the Vermont 1777 constitution were also heavily influenced by natural rights philosophy. Natural rights philosophy was pioneered by English philosopher John Locke. Locke argued that all men were born free and equal and have the right to life, liberty, and property.[12] These ideas are apparent in the Declaration of Independence and the newly-developed state constitutions, but—as many Americans celebrated the ideals of freedom and equality—they held thousands of Africans in bondage.

Vermonters seemed to see this contradiction more clearly than their American brethren. In Chapter 1 Clause 1 of the Vermont Constitution, Vermont recognized that “all men are born equally free and independent . . . therefore, no male person ought to be holden by law, to serve any person as a . . . slave.”[13] However, the abolition clause did include an important caveat: men could be held as slaves until they turned twenty-one and women could be held until they turned eighteen.[14] This led to the indenture of both poor white and black children.[15] Despite the inherent conflict in this caveat, the abolition of slavery was still a largely radical idea—and a radical implementation of natural rights philosophy. In fact, when Vermont was seeking admittance to the Union in 1791, the Southern states fought vehemently against it because of Vermont’s denunciation of slavery, which proved to be more powerful on paper than widespread in practice.[16]

Although natural rights theory was significantly impactful in Vermont’s Constitution, it was not the only political theory that inspired Vermonters. The Framers of the Vermont Constitution were also inspired by the classical republican tradition of New England. Classical republicanism was first devised by the Romans and gained popularity in Europe during the Italian Renaissance and the Enlightenment.[17] It emphasized self-sacrifice for the common good, civic virtue, and education.[18] Classical republicanism was largely adopted by the forefathers of early Vermonters. The Grants that would become Vermont were first settled by farmers from New England.[19] Their New Englander forefathers were the Pilgrims and Puritans who came to America seeking religious freedom. According to Alexis de Tocqueville, a French politician and traveler who analyzed America’s political culture, “Puritanism was not merely a religious doctrine, but it corresponded in many points with . . . republican theories.”[20]

The early New Englanders were famous for implementing classical republican ideals through their emphasis on collective unity and their use of town meetings for governance.[21] Vermonters took these ideas and further incorporated them into the 1777 Vermont Constitution. Chapter 1 of the Constitution, which effectively served as a bill of rights, was peppered with phrases alluding to classical republican beliefs. The Constitution asserted that “private property ought to be subservient to public uses, when necessity requires it;” “the government is . . . instituted for the common benefit;” “all freemen . . . have a right to elect officers, or be elected into office;” and “that every member of society hath a right to be protected . . . and therefore, is bound to contribute his proportion towards the expense of that protection.”[22] Additionally, the Vermonter’s Constitution allocated funding for public schools, demonstrating their value for education.[23] Vermont’s founding fathers used the doctrines of their ancestors to form a government that significantly extended suffrage and education access, further implementing some of America’s fundamental principles and beliefs.

The Vermont Constitution was fully infused with the principles and values of America. It included a nod to the revolutionary sentiment of the time period. It took ideas from the popular natural rights theory, and it borrowed from the New England heritage of classical republicanism. However, the most important part of the Vermont Constitution was not the ideals it borrowed, but the changes it implemented. Countless Framers discussed the importance of inalienable rights, representation, and the common good, but few people put their ideas into policies that benefited everyone—not just an elite few. Vermont’s 1777 constitution is truly significant because it did take measures to help all Vermonters—not just Protestant, property-owning, white men; it guaranteed full male suffrage, abolished slavery, and provided education access, leaving a legacy of which Vermonters can be justifiably proud.

[1]Thomas Jefferson, “Declaration of Independence,” July 4, 1776, www.archives.gov/founding-docs/declaration-transcript.

[2]“State and Continental Origins of the U.S. Bill of Rights,” Teaching American History, teachingamericanhistory.org/resources/bor/origins-chart/.

[3]Peter Onuf, “State-Making in Revolutionary America: Independent Vermont as a Case Study,” The Journal of American History 67, no. 4 (March 1981): 799, www.jstor.org/stable/1888050.

[4]“Constitution of Vermont,” July 8, 1777, avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/vt01.asp.

[5]Jefferson, “Declaration of Independence.”

[7]Christopher S. Wren, Those Turbulent Sons of Freedom: Ethan Allen’s Green Mountain Boys and the American Revolution(New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 2019), 6.

[9]Gary Aichele, “Making the Vermont Constitution: 1777-1824,” Vermont History Journal56, no. 3 (Summer 1998): 167, 169, vermonthistory.org/journal/misc/MakingVermontConstitution.pdf.

[10]“Constitution of Vermont.”

[12]“Locke’s Political Philosophy,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, plato.stanford.edu/entries/locke-political/#SelePrimSour; and We the People: The Citizen & the Constitution, 3rd ed. (Calabasas: Center for Civic Education, 2009), 17-18.

[13]“Constitution of Vermont.”

[15]Kari Winter, “Bordering Freedom but Unable to Cross into the Promised Land: Africans in Early Vermont,” Historical Reflections32, no. 3 (Fall 2006): 480, www.jstor.org/stable/41299385.

[17]Gordon S. Wood, The Idea of America: Reflections on the Birth of the United States(New York: Penguin Books, 2012), 60.

[18]Ibid., 67-68; We the People, 12-14.

[19]Wren, Those Turbulent Sons of Freedom, 1, 2.

[20]Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, trans. Henry Reeve (The Pennsylvania State University, 2002), 49.

[21]David Hackett Fischer, “Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America,” Jesse Woodson James, jessewoodsonjames.weebly.com/uploads/1/2/0/8/12083819/fischer-albionsseed.pdf.

5 Comments

As a born Vermonter still living in Vermont, I thank you for presenting a fine piece on the state’s constitution, Ms. Jaeger. It is a document that has gone through much modification but, unlike most early constitutions, has never been replaced. And, it is appropriate that your article appears so close to the 250th anniversary of the Breakenridge affair (July 18-19, 1771) which many consider the birth of Vermont.

I would like to add a couple comments. For one, while modern historians call independent Vermont a “republic,” eighteenth-century Vermonters never used the term. They always referred to themselves as a “state.”

Second, in addition to the D. of I., the writers of the Vermont constitution also relied heavily on the Pennsylvania constitution, even lifting sections directly for use in their own document. They also adopted a bit from Connecticut (some proposed calling the Grants, “New Connecticut”).

Lastly, to add to the background of the creation of this document one should understand that it is something of a compromise. Up until the mid-twentieth century, the Green Mountains created a political as well as geographical east-west divide. Lots of folks on the east side actually favored New York and others did not care for the Allens and their Arlington junto (westsiders). The American Revolution prompted the cliques to work together. I often wonder what would have become of the Grants had the war not happened.

Mike,

To answer your question of what would have happened had the war not intervened, I offer this from my recent book (written with Nick Muller and John Duffy), The Rebel and the Tory: Ethan Allen, Philip Skene and the Dawn of Vermont.

Philip Skene was in London when he was awarded the title of Lt. Governor of Ft. Ticonderoga and Crown Point in January 1775, which offered the prospect of this region becoming the fourteenth colony. When he attempted to return to the Grants to take up his new position, he was arrested when he stepped foot in Philadelphia that June in the time following Lexington/Concord. Had that not happened, in all likliehood he would have come to the Skenesborough area, established courts and ushered in favorable title decisions for the Grants settlers pursuant to his agreement with Allen. In short he would have put an end to all the disputes.

Regarding the Constitution itself see my masters thesis arguing that it was not much more than a symbolic gesture constituting treason against NY authority (available upon request). The settlers created it contrary to directions from the Continental Congress not to do s0. The reasons for its stated lofty ideals differ substantially from the accepted trope that we have become familiar with.

People tend not to want to get into the legal aspects of the Grants disputes, but if you want to truly understand them, it is necessary to become familiar with the court proceedings that the settlers relied on so heavily. Historians have avoided that area and the story of Vermont’s creation has suffered.

Greetings Gary,

I have your latest book in my “to read” pile and look forward to the experience.

I suspect VT would have continued on a course towards statehood although what that course would have been and what the result would have looked like–for me, at least–is subject to too many variables to make even an educated guess.

Knowing of your predilection for investigating the legal side of affairs, I most definitely would like to read your master’s thesis. It uses an angle of approach to early VT almost entirely new to me.

Hi Mr. Barbieri!

Thank you so much for commenting on my paper. You seem to have so much knowledge about the early history of Vermont—which, in researching for this paper, I found absolutely fascinating. There was so much I read about that I wasn’t able to include within the scope of the essay, yet I am sure there is still much more to learn. Do you have any book or article recommendations that expand on Vermont’s early history?

Thank you,

Sophie Jaeger

There are several collections of primary source documents available on-line including “Records of the Council of Censors,” an 1823 collection of documents, records, and laws compiled by William Slade, ten volumes of the “Records of the Council of Safety and Governor and Council,” “Index to the Papers of the Surveyors-General,” “Charters Granted by the State of Vermont,” and “Rolls of the Soldiers of the Revolutionary War.” You can find these, and others, on Google Books and/or Internet Archive.

There are droves of secondary sources on early VT, the most recent being Gary Shattuck’s “The Rebel and the Tory: Ethan Allen, Philip Skene, and the Dawn of Vermont” (if the name sounds familiar, he’s the other replier to this discussion). Others include Muller and Hand’s “In a State of Nature: Readings in Vermont History,” Muller and Duffy’s “Inventing Ethan Allen,” Sherman, Sessions, and Potash’s “Freedom and Unity: A History of Vermont,” Bennett’s “A Few Lawless Vagabonds,” Matt Jones’ “Vermont in the Making,” and Whitfield’s “The Problem of Slavery in Early Vermont, 1777-1810.”

There are also various theses (Gary Shattuck, for one) and dissertations and articles in publications like the Vermont Historical Society’s Vermont History.

There are more for each category but the above should give you a start and get you a ways along the early Vermont history trail. Good luck and enjoy.