Here’s one of the things I love most about Boston: If it were possible to drop Paul Revere in downtown today, he could, quite literally, find his way home. Not just to the site of his former home, but to his actual house. Incredibly, enough landmarks still exist in Boston that he could find his way back to his residence in the North End.

Before we set off with him, it’s worth stating the obvious: Revere would be starkly out of place in 2021. It wouldn’t be the noise of the city or the people that would likely trip him up. And it wouldn’t even be his sartorial choices. His leather apron and tricorn hat might actually help him blend in among the tour guides and character actors who regularly walk the streets of downtown Boston. But the sheer size of the buildings, cars, and paved streets, as well as the electricity, would probably give him pause. He’d also see something truly shocking on his walk home: his own grave.

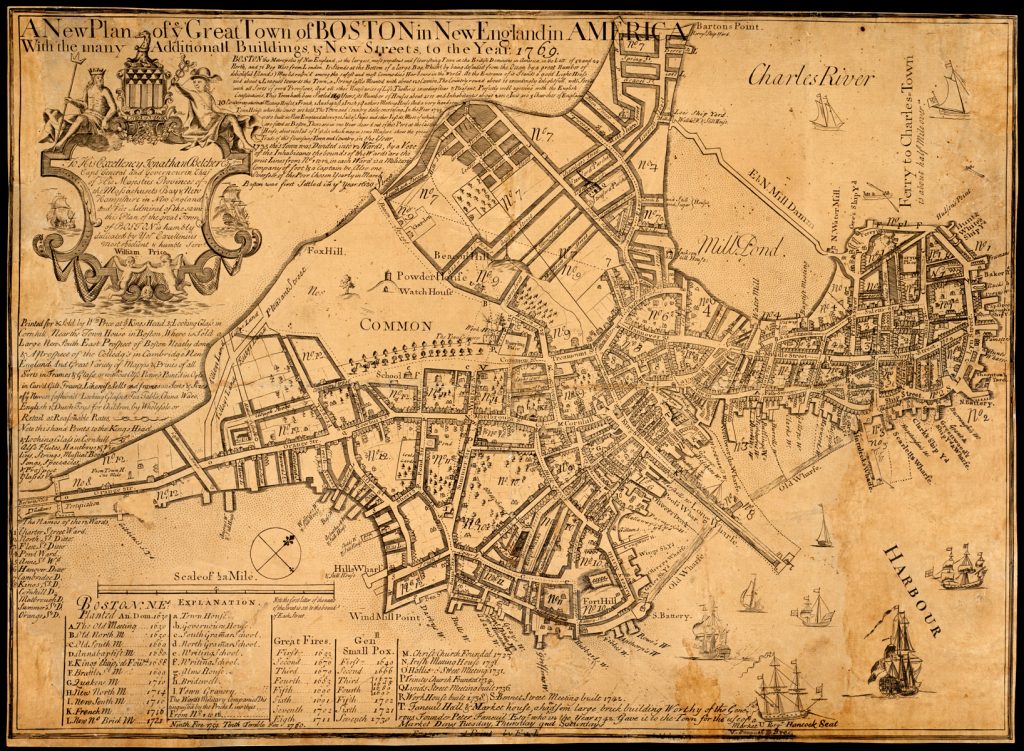

Paul Revere was born in Boston in 1735 and resided in town for over fifty years. He would know the layout of Boston’s crooked streets as well as anyone today, especially because he lived a long life, dying at the age of eighty-three. He witnessed many of the changes that began in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries as the town grew in size. (Boston became a city in 1822.) Colonial-era Boston was just two miles from tip to tip and surrounded almost entirely by water. The shoreline and city have expanded in the two centuries since his death. On his trip home, however, he won’t have to veer from Boston’s original Shawmut Peninsula.

Let’s follow Revere as he seeks the familiar. Along our route of a little over a mile, we’ll see sites that he’d recognize, and we’ll even uncover two time capsules—seriously!

Boston Common

Boston Common, Revere’s landing spot, was founded in 1634 and is America’s oldest public park. The town of Boston was founded in 1630, so the Common is nearly as old as the town itself and existed long before Revere’s father emigrated to Massachusetts from France. The park now, as in the 1700s, remains an open expanse of land with walkways and many trees.

Massachusetts State House

Looking up the hill from the park, one sees today, as they would have two hundred years ago, the State House, the capitol of Massachusetts. Its dome is covered in gold leaf, which might irk Revere, whose foundry covered the original wooden dome with copper fitting in 1803. Though his legacy atop the building is gone, it lives on in the foundation. Revere laid the capitol’s cornerstone in 1795 along with Gov. Samuel Adams, which leads us to our first time capsule. Inside the stone, Revere and Adams placed a box filled with coins and a silver plate commemorating the occasion. In his address that day, Adams said he hoped that the building would “remain permanent as the everlasting mountains.”[1] Revere would, no doubt, be pleased that the governor’s wish has been fulfilled and that the capsule has twice entranced the commonwealth’s residents. It was first opened in 1855 and rediscovered in 2015 as part of necessary repairs.[2] It was reburied that same year with some new objects, ensuring posterity will continue to delight in Revere’s time capsule.

As we ascend Beacon Hill to get closer to the State House, we’ll have an easier time walking up than we would have in the colonial era. The hill—today only a slight incline—used to be much steeper. A lot of it was cut down during Revere’s life. Once at the top, if Revere were curious enough to look around the east side of the State House to the parking lot, he’d notice a replica of the first monument to the American Revolution in the United States. The original was designed by Charles Bulfinch (who also designed the new state capitol) and was erected in 1790. It came down in 1811 during the levelling of Beacon Hill, so Revere, who died in 1818, would undoubtedly be surprised to see it standing again. Even stranger: Is it his imagination, or has it shrunk in 200 years? It has. The column today is half its predecessor’s size but includes Bulfinch’s original slate tablets.[3]

The State House is much larger than it used to be, with expansions on both sides, including the adjacent parking lot. The west wing sits on top of land previously owned by John Hancock. Revere might worry that if the stone mansion of such a prestigious figure no longer stands, it is unlikely that the wooden home of a silversmith still exists. But this trip will be full of surprises for Revere.

Hancock House

In the mid-nineteenth century, Boston’s increased population was outgrowing the tiny peninsula of colonial days. Landfill expanded the shoreline and livable area, but space was still needed downtown, so older buildings were considered for demolition, including Hancock’s mansion.[4] At this time, there wasn’t a national organization or leadership committed to preserving old buildings. Federal protection for historic landmarks didn’t come about until the first decades of the twentieth century.[5] Boston’s city charter only prohibited Boston Common and Faneuil Hall from being sold, which inadvertently privileged those two sites over other revolutionary relics.[6]

Shortly after Hancock’s death in 1793, his family sold some of their estate to the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, where it built the new state house.[7] In the early 1860s, Hancock’s descendants were ready to sell all of the remaining land and offered the home and many of its furnishings as a gift to the city.[8] The Boston City Council, however, didn’t raise enough funds to move the house, and in 1863 it was “ruthlessly swept away.”[9] A simple plaque on the gates of the capitol is the only indication that a Founding Father used to live there.

The destruction of Hancock’s house was the “catalyst,” according to historian Michael Holleran, for future preservation efforts in Boston.[10] The destroyed mansion seemed to have more value after it was gone because it rallied supporters who sought to prevent future demolitions. Citizens no longer trusted the city or state to preserve monuments that meant something to them.[11] Revere’s walk home is aided by these grassroots preservation efforts, as they ensured that many historic landmarks have survived.

Today, Revere could even follow a red brick path, called the Freedom Trail, that links sixteen sites from the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries. Many buildings on the Freedom Trail directly benefitted from the efforts of private individuals to preserve the Boston that Revere is seeing in the twenty-first century.[12] Given the millions of visitors who walk the route every year, it seems an obvious and easy decision to protect such buildings, but their continued existence was not inevitable.

Granary Burying Ground

Street names in Boston can be very literal, and as we descend Beacon Hill, we’ll come down Park Street, which borders the Common, and make a left on Tremont Street. Both of those streets are familiar to Revere, as is our next colonial site: the Granary Burying Ground. Protected from the busy street by an iron gate, it is the third-oldest cemetery in downtown Boston (out of four), but it, by far, houses the most prominent men of Revere’s day. The bodies of Samuel Adams, James Otis, John Hancock, and the victims of the Boston Massacre lie in this space. Revere’s father as well as his first and second wives were also buried here before him.[13] His plot is marked by a humble stone that reads, “Revere’s Tomb.” (A hip-height monument was erected decades after his death.) As he copes with seeing his final resting place and visiting loved ones, he may also notice that the rows of headstones are straighter than he remembers. In the mid-nineteenth century, the city rearranged them to make maintenance easier.[14]

King’s Chapel

After the emotional stop at the Granary Burying Ground, Revere gets back on Tremont Street and in two short blocks, he sees King’s Chapel and its burying ground, dating to the seventeenth century. The cemetery has undergone some cosmetic changes, but the church’s appearance hasn’t changed much since the mid-eighteenth century. There is one alteration, however, that Revere would be eager to see. In 1816, Revere’s foundry cast the bell for King’s Chapel, the largest it ever created.[15] After admiring his family’s work, he’d continue down School Street—another name from the colonial era—toward Old South Meeting House.

Old South Meeting House

Old South Meeting House, formerly a church, was erected in 1729 and was the site of an important gathering held immediately before the Boston Tea Party. Nearly five thousand people, by Samuel Adams’s estimation, crammed themselves into the meetinghouse to seek news about the Tea Act.[16] When the crowd learned that three ships had to land their tea and pay the required duties, costumed men outside the church began whooping.[17] The crowd inside started shouting, “Boston Harbor—a tea pot tonight!” and soon “a number of people huzza’d in the Street.”[18] The group flooded out to Griffin’s Wharf, where Revere and 150 other men smashed open tea chests and dumped them into the harbor.[19]

The building still stands in 2021 because of the efforts of determined people reeling from the loss of Hancock’s house. In the 1870s, Old South Meeting House was to be sold and levelled. The congregation wanted to move to a more fashionable neighborhood, didn’t see any point in preserving the building itself, and understood the great value the land held.[20] Demolition of the building began in 1876, the centennial of American independence, but a number of citizens banded together and bought the building and its land from a developer. For the first time, Americans had stopped the destruction of such buildings.[21]

Revere takes Washington Street for a few steps before seeing his next landmark. On the corner of School and Washington Streets sits a brick building with a gambrel roof that dates back to 1718. It once housed an apothecary, but today it’s leased by a Chipotle Mexican Grill (really).[22] In just another block, he’ll bump into another colonial building and be about halfway home.

Old State House

At the end of Washington Street, Revere would recognize the Old State House. He didn’t have much to do with the inner workings of the building, as this is where the governor and legislature worked, but he had a tremendous connection to its exterior. In addition to his midnight ride, this building helped to immortalize his name and work. It is the backdrop in his ubiquitous engraving of the Boston Massacre.

In Revere’s time, the Old State House stood—and still stands—in the middle of an intersection. In the 1870s, city officials wanted to widen the street and tear the old capitol down. Once again, private efforts saved the building.[23] Over the years, it has adapted to municipal improvements, including having a subway station installed in the basement in 1908.[24] It’s a beautiful example of the city finding a way to blend the old with the new.

Revere would likely notice a lion and unicorn—symbols of royal authority—perched on top of the building’s front corners. They were burned in 1776, so like the Revolution monument next to the State House, we can imagine Revere’s puzzlement at seeing these figures lording over the people below. Replicas went up in 1901, which is when and where our second time capsule was concealed. Unlike the first capsule, Revere never knew this one was placed, discovered, and rehidden inside the lion’s head. The capsule—filled with newspapers, campaign buttons, and other assorted items (sadly, no treasure map)—was discovered during a restoration project in 2014. Like the hidden box at the State House, this one also had new items put inside for safe keeping.

Looking down State Street, Revere would notice Boston Harbor in the distance. In the eighteenth century, the water came much closer to the Old State House. Boston began filling in the shoreline in the 1810s, but a second effort to expand it happened in the 1880s, so it’s much further back than he would recall. Not to worry: Faneuil Hall still stands and is near enough to the Old State House that once Revere spots it, we’ll be back on track.

Faneuil Hall

What we won’t see today is the original Faneuil Hall, which was built in 1742 and functioned as a marketplace on the bottom floor with a civic space above it.[25] The building sat in Dock Square, a part of town Revere knew very well. Despite the building being known as the “Cradle of Liberty,” the merchant who paid for it, Peter Faneuil, sold many goods, including enslaved women and men. (The idea of renaming the building has been discussed in recent years.) The funeral for the Boston Massacre victims was held here, as were protests against British taxes passed in the 1760s and 1770s. In 1805, Charles Bulfinch—our third piece by him, for those keeping score—expanded Faneuil Hall to its existing size, which means that while someone like Joseph Warren, who died in the Battle of Bunker Hill in 1775, wouldn’t recognize the remodeled structure, Revere’s long life means that he would.

Green Dragon Tavern

A short walk leads to one of Revere’s old stomping grounds: the Green Dragon Tavern. Today, the watering hole is on Marshall Street, but the original tavern was blocks away from where it currently stands and has no connection to the contemporary one. It’s likely Revere would want to stop for a beer to reflect on two defining moments in his political life that happened at the Green Dragon.

The first relates to increased tensions in 1775 between the crown and Bostonians. Revere met with other mechanics to monitor the movement of British troops. The silversmith recalled a tense atmosphere: “We were so carefull that our meetings should be kept Secret, that every time we met, every person swore upon the Bible.”[26] Despite the precautions, their secrets still leaked out because there was a spy in their midst: Dr. Benjamin Church. Revere claimed Church “was a high son of Liberty,” and the betrayal cut him deeply, even when remembering it decades later.[27]

The second event at the Green Dragon reveals Revere’s influence. The new federal constitution had been written in 1788 and was anything but a sure thing to be ratified, especially in Massachusetts.[28] Some prominent revolutionaries, including Samuel Adams, were skeptical about centralizing power in a federal government. Boston’s tradesmen, led by Revere, supported the Constitution and gathered at the Green Dragon Tavern to write resolves to sway Adams.[29] Revere brought them to the statesman, who was taken aback. Adams asked Revere how many mechanics were at the Green Dragon. More than the tavern could hold, he boasted. Adams pressed him about how many men overflowed into the streets. “More, Sir, than there are stars in the sky,” he said.[30] In reality, it was closer to 380 men, but Revere’s poetic license is appreciated.[31] Adams changed his mind, and the Constitution was ratified in Massachusetts and, ultimately, the United States.[32]

After stepping out of present-day Green Dragon and seeing a house built in 1767 that was owned by John Hancock, Revere would know he’s close to home and could take Hanover Street back to the North End. The North End was colonial Boston’s oldest and most crowded neighborhood, housing diverse residents, warehouses, shops, and distilleries. Sailors and artisans lived and worked here, as did families of privilege.[33] The neighborhood changed over the centuries and became a haven for new immigrants. Irish and Jewish settlers and then Italians put down roots there. It is the Italian presence that remains in this section of Boston today. One traveler in 1959 observed of the North End, “Despite the Italian atmosphere, the immortality of Paul Revere marks it as still Boston.”[34]

Likely filled with anticipation, Revere turns off Hanover Street toward North Square to see if his home is still standing. It is—truly remarkable, since it was old when he bought it. It’s the oldest remaining structure in Boston, having been built around 1680.[35]He owned the house for thirty years from 1770 to 1800. After that, it served as a boarding house, shop, bank, and cigar factory, among other things.[36]

Paul Revere House

That Revere’s house is a museum now is owing to, as with the Old South Meeting House and the Old State House, private individuals. To save it from demolition, a descendent of Revere’s purchased the home in 1902. The Paul Revere Memorial Association was formed soon after, and in 1908, the house reopened as a museum. The architect who restored it wanted it to resemble the house as it likely appeared in the seventeenth century, so Revere would likely be slightly confused by its exterior today.[37] But he would, undoubtedly, be home.

[1]Columbian Centinel, July 8, 1795, Genealogy Bank.

[2]David Scharfenberg, “Coins, Newspapers Found As Time Capsule Is Opened,” Boston Globe, January 7, 2015.

[3]Alfred F. Young, The Shoemaker and the Tea Party: Memory and the American Revolution (Boston: Beacon Press, 1999), 113-4, 200-1.

[4]Walter Muir Whitehill and Lawrence W. Kennedy, Boston: A Topographical History, 3rd ed. (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2000), 150-173. In the mid-nineteenth century, the city filled in the Back Bay area, further increasing the available land.

[5]Charles B. Hosmer Jr., Presence of the Past: A History of the Preservation Movement in the United States before Williamsburg (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1965), 21.

[6]Michael Holleran, Boston’s “Changeful Times”: Origins of Preservation and Planning in America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998), 86.

[7]Lorna Condon and Richard C. Nylander, “A Classic in the Annals of Vandalism,” Historic New England 6, no. 1 (Summer 2005): 45.

[8]“Report of Committee on the Preservation of the Hancock House 1863,” in Documents of the City of Boston for the Year 1863 (Boston: J. E. Farwell & Co., 1863), 2: 6.

[9]Holleran, Boston’s “Changeful Times,”92; Hosmer, Presence of the Past, 39; Edmund Quincy, Life of Josiah Quincy (Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867), 38.

[10]Holleran, Boston’s “Changeful Times,” 94.

[11]Hosmer, Presence of the Past, 21, 40, 102-6, 229.

[12]Marc Callis, “The Beginning of the Past: Boston and the Early Historic Preservation Movement,” Historical Journal of Massachusetts 32, no. 2 (Summer 2004): 126-8.

[13]Esther Forbes, Paul Revere and the World He Lived In (Boston: Mariner Books, 1999), 451.

[14]Holleran, Boston’s “Changeful Times,” 85.

[15]“A Brief History: The Casting of The Revere and Son Bell,” kings-chapel.org/briefhistorykc.html.

[16]Samuel Adams to Arthur Lee, December 31, 1773. Harry Alonzo Cushing, ed., TheWritings of Samuel Adams, vol. 3 (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1904), 74; Boston Gazette, December 27, 1773, The Annotated Newspapers of Harbottle Dorr Jr., Massachusetts Historical Society Online.

[17]Benjamin L. Carp, Defiance of the Patriots: The Boston Tea Party & the Making of America (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010), 120-3.

[18]Cushing, Writings of Samuel Adams, 3: 72; Harlow Giles Unger, American Tempest: How the Boston Tea Party Sparked a Revolution (Boston: Da Capo Press, 2011), 5, 165.

[19]L. F. S. Upton, “Proceedings of Ye Body Respecting the Tea,” William and Mary Quarterly 22, no. 2 (April 1965): 298; Benjamin Bussey Thatcher, Traits of the Tea Party: Being a Memoir of George R. T. Hewes (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1835), 262; Young, The Shoemaker and the Tea Party, 56-7. Revere appeared on the first list of the Boston Tea Party participants, which was published by Thatcher in 1835.

[20]Holleran, Boston’s “Changeful Times,” 94-104.

[21]Ibid., 109; Hosmer, Presence of the Past, 102-6.

[22]For more on the preservation of this building, see Whitehill, A Topographical History, 218-9.

[23]Holleran, Boston’s “Changeful Times,”105-9.

[24]Hosmer, Presence of the Past, 107; Boston Landmarks Commission, The Old State House, December 13, 1994, cityofboston.gov, 4.

[25]Charles Bahne, Chronicles of Old Boston: Exploring New England’s Historic Capital (New York: Museyon, 2012), 22-3.

[26]Edmund S. Morgan, ed., Paul Revere’s Three Accounts of His Famous Ride (Boston: Revolutionary War Bicentennial Commission and Massachusetts Historical Society, 1967), The Deposition: Corrected Copy.

[27]Ibid.; John A. Nagy, Dr. Benjamin Church, Spy: A Case of Espionage on the Eve of the American Revolution (Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, 2013), 95-112. In 1796, Revere wrote an account of his 1775 midnight ride, and he harped on Church for much of it.

[28]George H. Haynes, “The Conciliatory Proposition in the Massachusetts Convention of 1788,” Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society 29 (October 1919): 299.

[29]Daniel Webster, The Works of Daniel Webster, vol. 1 (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1860), 302; Gordon S. Wood, TheAmerican Revolution: A History (New York: Modern Library, 2002), 153; Jeremy Belknap minutes, February 6, 1788, Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society 3 (1855-8): 303-4. Artisans were supportive of the Constitution because they thought it would help boost trade by cutting down on British imports.

[30]Webster, The Works of Daniel Webster, 1: 303.

[31]Pauline Maier, Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787–1788(New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010), 164.

[34]Chiang Yee, The Silent Traveller in Boston (Carlisle, MA: Applewood Books, 1959), 229.

[35]Holleran, Boston’s “Changeful Times,”216.

[36]“Historic Buildings: Paul Revere House,” paulreverehouse.org/paul-revere-house/.

[37]Callis, “The Beginning of the Past,” 126-8; “About: Mission & History,” https://www.paulreverehouse.org/mission-history/; “Historic Buildings.”

12 Comments

Nicely done Brooke and great photos too. It brought back fond memories of my own Boston tour and I learned considerable new material as well. You might add that a French officer killed by a Boston mob in September 1778, Chevalier Gregoire de Saint-Saveur, was buried at King’s Chapel and a plaque (in French) in his honor is still at the site. See my article on this website, Why Did a Boston Mob Kill a French Officer (Oct. 23, 2014). Let’s not forget the French! https://allthingsliberty.com/2014/10/why-did-a-boston-mob-kill-a-french-officer/

Christian McBurney

Christian, thank you! I’ve read the article you wrote and have cited it in another project I’m working on. 🙂

What a lovely and highly readable article! Thank you for this insightful tour through beautiful downtown Boston, through the eyes of a truly great and underappreciated Patriot.

This is a terrific tour! If you’re interested in the city’s architecture, have a look at the Boston entries in SAH Archipedia as well, the online encyclopedia of the built environment published by the Society of Architectural Historians and the University of Virginia Press: https://sah-archipedia.org/essays/MA-01.

Thank you for the suggestion!

Terrific article! I love that map of Boston and used it frequently while researching my book, which Paul Revere is a prominent character in. The Esther Forbes book is also quite wonderful—it’s like she knew Revere personally. I think Paul Revere would be happy to learn about the recent passage of the Deborah Sampson Act—which will improve health care for female veterans. He was instrumental in helping our first female veteran receive a pension for her service in the American Revolution.

What a wonderful article.

Obviously, a lot could not be saved. The (irascible) historical novelist, Kenneth Roberts, graduated from Cornell in 1908 and came to Boston as a young man. Looking back in 1949, he wrote in his memoirs:

“Opposite City Hall was Province Court and the old Province House, haunt of light ladies either with or without their dubious escorts, but source of the best onion soup in Boston or anywhere else. I cursed the numskulls who let it be torn down, that ancient seat of military pomp and power, in which General Gage, General Howe, General Clinton, General Burgoyne, Lord Percy and their glittering, scarlet-jacketed subordinates had gathered on the steamy hot morning of June 17, 1775 and issued the incredibly stupid orders that sent a thousand helpless soldiers to dreadful mutilation on a hilly cow pasture above Charlestown — the Province House, long the true heart and hub of Boston, whose walls had seen more great and famous men than any other building in Ameria; where, through a long and cheerless winter, harried and hungry Loyalists from every hole and corner in Massachusetts had shuffled through snow and slush for the meager rations doled out to them by their fellow Loyalist, Benjamin Thompson, who became Count Rumford and one of Europe’s foremost scientists.

“But the Province House was torn down so a street could be widened. It was in the way of City Hall. Yes, the British who met in the Province House were often stupid, but Boston has had City Fathers who were stupider — much, much stupider! Much!”

Thank you for the very enjoyable and knowledgable tour down Revere’s Memory Lane. One other building Revere would notice is his cousins the HIchborn’s brick house just across the courtyard from his house. He would also see that the adjacent 17th home of his next-door neighbors, built by the Barnards, is missing – demolished in the late 19th c. Fortunately we have enough old views of North Square to depict it as it was in the time of Revere. My illustrations of it are in the Historic Structure reports on the Revere and Hichborn Houses. He would enjoy seeing several of the items he made, including a bell and cannon (mortar), as well as silver and household items exhibited at the PRMA museum.

I agree that Revere would be thrilled to see the Hichborn House and some of his items on the display in the wonderful Paul Revere house and visitor center!

This is a fun article, but I can’t let you get away with the canard that Boston was founded in 1630. Episcopal priest Rev. William Blackstone bought it from the Indians in 1623 for his colony of about 25. When John Winthrop and his Congregationalists arrived in 1630, Blackstone invited them to share in the colony. Winthrop asked if he could rename Shawmut as “Boston,” so that’s where 1630 comes in. Winthrop, with force majeure, ordered all Episcopalians to leave in 1634, so Blackstone turned his farm into the Boston Common forever and moved to Rhode Island, which he founded 2 years before Roger Williams arrived!

Thank you for the kind words. I love Forbes too–she has such a way of setting scenes and introducing people.

That Chipotle was actually a bookstore for most of it’s history. In the mid 19th century, famous authors like Longfellow and Emerson were patrons. It was a bookstore as late as the 1980s, when I bought several books there.

Also, on nearby Milk St is a plaque on a building marking Benjamin Franklin’s birthplace.