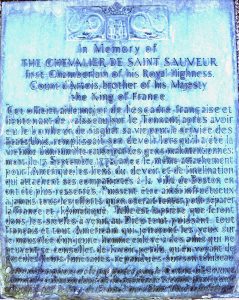

Some twelve years ago, as I was walking along Boston’s Freedom Trail with my family, I noticed an obelisk and monument in the front yard of King’s Chapel. As I peered closer at it, I read the title to the inscription:

In Memory of

THE CHEVALIER DE SAINT SAUVEUR

first Chamberlin of his Royal Highness,

Count d’Artois, brother of his Majesty

the King of France.

The remainder of the inscription was in French, which I thought to be odd. I noticed the words “mort le 15 Septembre 1778” and, having some knowledge of French, determined that the named officer had died on that date. With my wife and young children in tow, I could not spend more time at the site and had to move on (a long-running problem), but it left me wondering what the story was behind that unusual monument. I discovered it six years later as I was researching my book, The Rhode Island Campaign: The First French and American Operation of the Revolutionary War.

Let’s start the story on July 28, 1778, with the appearance off of Newport, Rhode Island, of a French squadron under the command of Charles Henri Théodat, Comte d’Estaing. Appointed by King Louis XVI to work with his new allies in attacking the British in North America, d’Estaing had eleven ships-of-the-line, one 50-gun ship, and three frigates. The ships carried 2,500 French army soldiers and marines, as well as some 8,000 sailors. D’Estaing was ready to join forces with American Continental, state and militia troops from New England, commanded by Major John Sullivan, to lay siege to Newport.

This initial French campaign started auspiciously, with French naval maneuvers causing the Royal Navy to blow up or scuttle five frigates, two sloops and three armed galleys carrying a total of 210 guns, the worst loss of the war in the former thirteen colonies for the Royal Navy. But the operation began to sour due to American delays in gathering troops and misunderstandings between Sullivan and d’Estaing.

Finally, Sullivan landed his troops on the northern part of Aquidneck Island on August 9—to the great annoyance of French officers, who wanted the glory of landing first. D’Estaing, with his ships having sailed past Newport in Narragansett Bay virtually undamaged, ordered his troops to join the American allies. When, later that same day, a British fleet cobbled together by Admiral Richard Howe showed up outside Narragansett Bay, d’Estaing ordered his stronger fleet to chase after it. But just as the opposing fleets were about to engage in a classic sea battle, a fierce storm kicked up, which forced both fleets to separate and ride out the fierce wind and waves. The ensuing gale damaged the French fleet more than the British fleet—d’Estaing’s flagship Languedoc alone lost all three of its masts and barely escaped capture by a 50-gun ship. The French fleet limped back to Narragansett Bay, where d’Estaing informed Sullivan that his ships required immediate repairs in Boston.

The French decision to depart Narragansett Bay shocked and angered both American officers and soldiers alike, who were depending on French naval superiority to get behind British lines. They were furious at the French for what they viewed as abandoning them in the middle of the siege. At this time, Sullivan’s troops were dug in, in Middletown, opposite British defensive fortifications just outside Newport. Deciding that a frontal assault was impractical, Sullivan chose to wait and see if the French fleet would return in time to assist him.

On August 28, Sullivan received word that General Henry Clinton was on his way from Long Island with a fleet of ships and 4,000 troops to try to trap the American army on Aquidneck Island. Sullivan immediately ordered a night retreat north to a defensive line anchored by Butt’s Hill in Portsmouth. The next morning, the commander of the British army on Aquidneck Island, Major General Robert Pigot, ordered his troops up the island’s East and West Roads in a bid to cut off shifting American forces. But Sullivan’s army, which included some Continental regiments that had been in action in the recent Battle of Monmouth Courthouse, fought well and held them off. The next night, Sullivan’s soldiers were successfully transported on small boats off the island.[1]

Proud of their army’s conduct in Rhode Island, many of Sullivan’s officers remained angry with the French. Lieutenant Colonel John Laurens summarized this view, writing for a Charlestown, South Carolina, newspaper: “The action of the 29th and our subsequent retreat have done honor to the American arms and consoled us in some degree for the cruel disappointment occasioned by the unexpected depart of the French squadron.”[2] A bitter Salem officer spoke for many when he wrote, “There never was a greater spirit seen in America for the expedition, and greater disappointment when Mr. Frenchman left us.”[3]

Ordinary New Englanders, too, blamed the French for the expedition’s failure. A British officer held captive in Connecticut noted the shifting mood of ordinary soldiers passing through town. Departing for Rhode Island these troops had been “very merry,” and in jest “used to call us Lobsterbacks.” But on their return, “they now skulk through the town and want to be unnoticed; but as we are generally on the [village] green, by which they all pass, we recognize our old friends and ask them if the island has surrendered. Their only return is a shake of their head, and a heavy curse on the French, for leaving them in the lurch.”[4] A Hessian prisoner who during the day had the run of Brimfield, Massachusetts, wrote, “Everywhere I had gone, Rhode Island was the topic of conversation. Everyone wished the French ill, some even cursed the whole alliance with France.”[5]

Boston, too, roiled with anger at the French. While Patriot leaders such as John Hancock and Dr. Samuel Cooper welcomed the arriving French fleet on August 28, its residents had a different attitude. The people of Protestant-dominated Boston had long been hostile to France, seeing it as the main cause of a half-century of colonial wars in New England and the leading promoter of the hated Catholic Church. Indeed, as late as November 5, 1777, the laborers of Boston celebrated Guy Fawkes Day, making it an anti-Catholic rally at which large effigies of the Pope and the Devil were paraded and then burned.[6] If it was not too difficult for Boston’s elites to become fast friends with the French, it was not as easy to change the historic prejudices of Boston’s working class.

In September 1778, a Loyalist intelligence report provided to the British secret service accurately described the mood of ordinary Bostonians: “The leaders of Boston on good terms with the French officers, but the people discontented. . . . The French connection disagreeable to all ranks of people. They make no doubt they will be able to conquer Britain with the assistance of France, but expect that after that is done France will next conquer them.”[7] Resentment of the French among Boston ship workers ran so high that they at first refused to repair d’Estaing’s damaged ships. “I saw very plainly when I was at Boston that our ancient hereditary prejudices were very far from being eradicated,” wrote John Laurens.[8] To him, many Bostonians still thought of France as the enemy of yesteryear, not as an ally.

French officers and sailors were, in turn, upset at the Americans. In his official army orders, General Sullivan, not once, but twice, had insulted his French allies for departing the American army during the siege of Newport. The French so far had lost many men. Hundreds of d’Estaing’s sailors and soldiers had fallen desperately ill on the Atlantic crossing, with dozens dying; perhaps twenty Frenchmen were killed after their ships had sailed after Howe, back past Newport’s gauntlet of land-based artillery; and thirty-nine Frenchman on board the 74-gun Caesar had died fighting a British ship. Its captain, Chevalier de Raimondis, after having his arm shot off in the conflict, declared that “I am ready to lose my other arm in the cause of the Americans.”[9] Despite these sacrifices, the French were being criticized and insulted in Boston.

On September 8 the tense environment exploded in a tragic violent confrontation. The French navy had established a bakery in Boston in order to make bread to feed their sailors and soldiers. Suddenly, heated exchanges between the French soldier-bakers and certain Bostonians turned into a riot. Learning of the disturbance, two French officers, apparently bringing French grenadiers with them, rushed to the scene to end it: Chevalier Gregoire de Saint-Sauveur, a twenty-eight-year-old lieutenant of the Tonnant, and one-legged Lieutenant George René Pléville le Pelley of the Languedoc, one of d’Estaing’s favorites. The two men succeeded in diffusing tensions, but on their return, they were set upon by some fifty men, clubbed brutally in their heads, “and left for dead.”[10] Within a week, Saint-Sauveur, who had been viciously struck above the right eye, died from his injuries.

D’Estaing and his fellow officers were appalled at the attack and mourned the Chevalier’s death. The victim was not just any nobleman—he had held the post of chamberlain to the powerful Comte d’Artois, the brother of King Louis XVI, and he was the brother-in-law of d’Estaing’s second-in-command, the Comte de Breugnon.[11]

Boston’s Patriot leaders, shocked by this turn of events, now realized that anti-French feeling had gone too far. In a conciliatory gesture, the Massachusetts Assembly voted to erect a memorial to the fallen officer.[12] And John Hancock did fine work entertaining and appeasing d’Estaing and other French officers. Not only did the Boston merchant patrol the streets to insure there were no more anti-French disturbances, he also persuaded the city’s shipbuilders to repair the French ships.[13] Sullivan, too, withdrew his insulting orders and apologized to d’Estaing.

Confusion arose as to who was responsible for the riot. On September 9, the Massachusetts Council, explaining that persons “unknown” had committed the outrage against the French officers, offered a $300 reward for information leading to their arrest.[14] In his history of the American Revolution, the Reverend William Gordon, who knew many of the American leaders, wrote, “None of the offending persons having been discovered, notwithstanding the reward that was offered, it may be feared that Americans were concerned in the riot.”[15]

Boston’s September 14 edition of the Independent Ledger blamed the riot on captive British seamen and some of the remaining prisoners from the Convention Army that had surrendered at Saratoga. Rather than remain captives, they had volunteered for service on a Boston privateer. “A body of these fellows, demanded bread of the French bakers,” the newspaper stated, and “being refused, they fell upon the bakers with clubs, and beat them in a most outrageous manner.”

There were other indications that the mob consisted of American sailors (probably also accompanied by dockworkers). The day after the riot, Major General William Heath, the commander of American forces in Boston, informed d’Estaing that “American sailors” had been involved in the affray, including some from the privateer Marlborough.[16] In his memoirs, after he had more time to learn the accurate facts, Heath still blamed American sailors.[17] The Comte de Breugnon, who mentioned specifics of the deadly riot in a contemporary letter, blamed it on Americans, as did another senior French officer.[18]

The day after the riot, an unsure d’Estaing advised his chief baker, an American, to determine if any future rioters were “Americans or traitors to their country,” meaning Tories.[19] Yet it seems unlikely that a mob of Tories in Patriot-controlled Boston would have been responsible for the attack.

More evidence that American sailors were responsible for Saint-Sauveur’s death was found in the continued strife between them and the French. Subsequent fights were reported to have occurred between the French and Americans on September 26 and 27.[20] On October 5 there was a brawl between the French and “some American seamen,” followed by rumors that a “much greater disturbance” would take place the next night. At this, the Massachusetts Council ordered Heath to call out the troops and advised the Sheriff of Suffolk County to take care “that no unlawful measure be taken in quelling the riot.” On October 12, after sailors on board the Massachusetts state navy brig Hazard had verbally abused French sailors on the nearby Dauphin, the Massachusetts Council instructed the Hazard’s captain “to order his men not to treat the men on board the Dauphin with any opprobrious language in time to come.”[21]

Given the city-wide shortage of bread caused by the sudden appearance in Boston of 10,000 sailors and soldiers on board the arriving French ships, it is very plausible that American sailors caused the riot. After all, they wanted to go on voyages to capture British vessels and hopefully become rich, but their ships needed adequate food stores before they could sail. American sailors and waterfront workers were probably also irritated at seeing French quartermasters with bags of King Louis XVI’s silver and gold coins to pay local retailers, while they had only depreciated paper money to compete for foodstuffs in short supply. Adding these circumstances to what the Americans believed to be the French flight from Newport and the historic anti-Catholic feeling in Boston, the environment was a volatile one.

One interesting contemporary source had both British sailors and Boston inhabitants participating in the riot that killed Saint-Sauveur. One of the privateers in Boston finally headed out to sea around September 16, but then had the bad luck to be almost immediately captured by the British frigate Unicorn and sent to New York City. That city’s Loyalist newspaper, the Royal Gazette, reported the following in its September 19 edition:

The master and crew inform us that, a few days before she sailed, a quarrel arose between British seamen, who were prisoners on their parole at Boston, and some of Monsieur d’Estaing’s crews, that this quarrel was settled without any bad consequences; but on the succeeding day, the parties met near a tavern, when the French brought a superior force, and the English would have been overpowered, had not 200 of the inhabitants [of Boston] took part against the French, and a bloody tragedy ensued.

Of course, the report of captive American seamen in a Loyalist newspaper must be viewed with some skepticism. But this report may be the most accurate account. The fact that a quarrel arose on September 7 is consistent with the continuing strife that occurred between French and American sailors after September 8. The reference to the French bringing a superior force is probably to the rescue party led by Saint-Sauveur and Pelley. The most interesting reference is the term “inhabitants.” D’Estaing most wanted to know, were the attackers British subjects, American seamen, or Boston inhabitants? In the first two cases, the melees could be understood—after all, the British were their enemies and many of the seamen did not hail from Boston. But if the attackers were residents of Boston, that could be a serious blow to the allied cause. It is not clear whether the newspaper editor meant either American seamen or Boston residents, or both.

D’Estaing sensibly sought to defuse matters and acted on the assumption that the attack had been instigated by British sympathizers. He later informed General Heath that he was persuaded that Boston’s inhabitants had had no hand in the affray—to the great relief of Boston authorities. [22] In responding to Heath’s information that sailors on board the American privateer Marlborough appeared to have been involved in the riot, d’Estaing diplomatically responded, “Some sailors, many of whom are deserters from the enemy, like those said to be found on the privateer Marlborough, have proved no doubt suitable instruments to perform what has been done.”[23]

In a letter to d’Estaing, based on information sent to him, Washington stated that he had “no doubt that the plot originated with the [British] convention troops and that British sailors in our service were the immediate instruments of their malice.” The commander-in-chief also mentioned that two of the “assassins” were said to have been wounded by French grenadiers.[24] Interestingly, Washington focused on who started the melee, and not on American seamen and Boston inhabitants who may have joined in later.

Carried through the city by eight French sailors, Saint-Sauveur’s body was buried quietly at night, without the fanfare of a public funeral, in the crypt of King’s Chapel.[25] On September 28, d’Estaing drafted the inscription for the dead nobleman’s monument and had it distributed throughout his fleet, so that his men would know the honor granted to the lieutenant. The French admiral wrote that Saint-Sauveur, “after having had the happiness in risking his life for the United States, was in the performance of his duty when he became the victim of a tumult caused by persons of evil intent; dying with the same attachment for America, the ties of duty and sympathy which bind his compatriots to the City of Boston have thus been drawn tighter.”[26]

D’Estaing seemed satisfied with the efforts of Washington, Hancock, and others to repair relations, and he was touched by the legislation passed to build a monument to Saint-Sauveur’s memory. Boston leaders feted French officers to a grand banquet at Faneuil Hall on September 25, and the next month d’Estaing hosted Boston’s elite on board the Languedoc. In early November, d’Estaing’s squadron set sail for the Caribbean, and the Saint-Sauveur affair was quickly forgotten amidst the many other tragedies wrought by the war.

In the early 1900s, a Boston historian discovered that the penny-pinching Massachusetts General Assembly had never spent the funds to erect the monument for Saint-Sauveur. In 1905, the Massachusetts legislature authorized $1,500 to erect the monument, but again nothing happened.[27]

Only when France and America were about to be allies again in a major conflict, in World War I, was the monument erected at King’s Chapel. The dedication of the monument finally occurred in May 1917, one month after the United States entered the war as an ally of France. The fourteen-foot-high obelisk, made of concrete granite, was designed to be consistent with similar monuments erected in England in the eighteenth century.[28] If the reader is ever in Boston on the Freedom Trail, do take a few minutes at the memorial to remember the Chevalier Saint-Sauveur.

[1] For the Rhode Island Campaign and the Battle of Rhode Island, see McBurney, Christian M., The Rhode Island Campaign: The First French and American Operation of the Revolutionary War, Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2011, chapters 4 to 10.

[2] Extract of a Letter from an Officer in General Sullivan’s Army (probably John Laurens), Sept. 1, 1778, in Charlestown Gazette, Oct. 8, 1778.

[3] G. Williams to T. Pickering, Sept. 12, 1778, Timothy Pickering Papers, microfilm reel 17, Mass. Hist. Soc.

[4] Diary Entries, Aug. 12 & 30, 1778, in Benians, E. A. (ed.), A Journal by Thomas Hughes . . . . (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1987), 35 and 37.

[5] Diary Entry, Aug. 31, 1778, in Lynn, Mary C. (ed.), An Eyewitness Account of the American Revolution and New England Life: The Journal of J.F. Wasmus, German Company Surgeon, 1776-1783 (New York, NY: Greenwood Press, 1990), 117.

[6] As late as Nov. 5, 1778, the records of the Boston selectmen show that the Massachusetts Council and that board were trying to clamp down on the town’s traditional anti-Catholic parades. Boston Town Records, 25:79.

[7] Quoted from an unknown person who was in Boston on Sept. 21-22, 1778, in British Intelligence Memorandum Book, July 21–Nov. 10, 1778, MMC-2248, Manuscript Reading Room, Library of Congress.

[8] J. Laurens to H. Laurens, in Chesnutt. David, et al. (eds.), The Papers of Henry Laurens (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 1994),14:358.

[9] Quoted in McBurney, Rhode Island Campaign, 130.

[10] Extract of a letter from Comte de Breugnon, Oct. 10, 1778, in Stevens, B. F. (ed.), Facsimiles of Manuscripts in European Archives Relating to America 1773-1783 (London: Whittingham & Co., 1895), 23:1974 (fifty men attacked the French officers on their return); extract from the log book of the Languedoc, Sept. 28, 1778, quoted in Smith, Fitz-Henry, Jr., “The French at Boston During the Revolution,” The Bostonian Society Publications 10:48-49 (1913).

[11] Same sources as in prior note.

[12] Resolution, Sept. 16 1778, in Acts and Resolves . . . of the Province of Massachusetts . . . . (Boston, MA: Wright & Potter, 1918), 476.

[13] Unger, Harlow Giles, John Hancock, Merchant King and American Patriot (New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, 2000), 275-77; Extrait du Journal d’un Officier de la Marine(France: Privately Printed, 1782), 41 (“We owe a lot to Mr. Hancock, who restrained the people, going on patrol himself at night. Without that, we would have had to take refuge on board our vessels.”).

[14] Proclamation, Massachusetts Council, Sept. 9, 1778, in Massachusetts Senate Report Relative to a Memorial of the Chevalier de St. Sauveur, No. 336, April 28, 1905 (“Senate Report”), 11. The Senate Report collects many of the documents related to Saint-Sauveur’s death.

[15] Gordon, William, The History of the Rise, Progress, and Establishment of the Independence of the United States of America . . . . 3rd edition(New York, NY: John Woods, 1801), 2:394.

[16] W. Heath to C. d’Estaing, Sept. 9, 1778, in “Heath Papers,” Massachusetts Historical Society Collections,7th Series, 4:2, 268 (1904).

[17] Heath, William, Memoirs of General Heath (Boston, MA: I. Thomas and E. T. Andrews, 1798), 178.

[18] Extract of a letter from C. de Breugnon, Oct. 10, 1778, in Senate Proceeding, 21; extract of letter from Chevalier de Borda to C. d’Estaing, Sept. 9, 1778, in Noailles, Vicomte de, Marins et Soldats Français en Amérique . . . . (Paris, France: Librairie Académique Didier, 1903), 46.

[19] C. d’Estaing to W. Heath, Sept. 10, 1778, in “Heath Papers,” Massachusetts Historical Society Collections,7th Series, 4:2, 269 (1904).

[20] Noailles, Marins et Soldats Français en Amérique, 46.

[21] Smith, “The French at Boston During the Revolution,” The Bostonian Society Publications 10:49-50 (1913) (citing Massachusetts Archives).

[22] C. d’Estaing to W. Heath, Sept. 10, 1778, in “Heath Papers,” Massachusetts Historical Society Collections,7th Series, 4:2, 269 (1904).

[23] Ibid.

[24] G. Washington to C. d’Estaing, Sept. 29, 1778, in Chase, Philander D. (ed.), The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2008), 17:182.

[25] Noailles, Marins et Soldats Français en Amérique, 46 (quoting the Secretary of the French squadron, named Grandclus; crediting Dr. Samuel Cooper with finding the burial site); see also recollections of a Franciscan monk with the French squadron, quoted in Smith, “The French at Boston During the Revolution,” The Bostonian Society Publications 10:46 (1913).

[26] Extract from the log book of the Languedoc, Sept. 28, 1778, quoted in Smith, “The French at Boston During the Revolution,” The Bostonian Society Publications 10:48-49 (1913).

[27] Smith, ibid, 52.

[28] Smith, Fitz-Henry, Jr., The Memorial to the Chevalier de Saint Sauveur, The History of the Monument and of the Votes to Erect it, and an Account of the Ceremonies at the Dedication, May 24, 1917 (Boston, MA: Bostonian Society, 1918), passim.

3 Comments

Do you mean the Boston’s hundred year (British) hatred of the French didn’t disappear instantly when they magically became Americans?

Old grudges die hard.

Great article about the killing of St. Saveur in Boston.

Just to add a comment: d’Estaing was determined to have the last word.

On 5 November 1778, William Tudor wrote from Boston to Major Samuel White: “As to pleasure we have even less than we had when you left us except a Ball given last Thursday Evening by Genl Hancock with a View of gratifying Count D’Estang (sic) with a sight of the Ladies of Boston. Accordingly a general Invitation was given to every Lady of any Note in Town. And upwards of a hundred fine women and exceedingly well dressed assembled to see a Collection of the principal Officers of the Fleet, four from Each Ship being [sele?]cted – instead of which, the Count and 3 Officers who attended him [Tear where letter had been opened] The French officers were made up of Midshipmen and Second Lieutenants and a few of the Land Officers – who were dressed in the most infamous manner – Their Heads were not powdered nor even combed. Two or three had Leather Breeches on, and one danced with a checked (sic) Handkerchief round his Neck. The Admiral came in at 8 o’clock and went away at 9. Everything carried the appearance of Insult rather than otherwise and strongly tended to confirm the dislike in which Frenchmen are held.”

Misc. Mss., Tudor, William, New York Historical Society

Bob Selig

Very interesting article! I found it especially interesting because I had read about the episode in Esther Forbes’ ‘Paul Revere and the World He Lived In’– a wonderful book.