Despite the rescission of the Stamp Act in 1766, many imperial controversies persisted in New York City. Leading among them were:

- The annual demands of the royal governor for funds to support the troops quartered in the town;[1]

- The continuing post-(French and Indian) war recession;

- The Townshend taxes of 1767, which of course distressed all the colonies;

- A dearth of hard specie, required to pay the taxes;[2]

- Increasing irritation with the presence of troops in the city, particularly when they took “moonlighting” jobs away from local people; and

- Official refusal to respond to the Boston Circular Letter of February 1768.

But one irritation symbolically managed to encapsulate the frustration of the entire situation: the perpetual contretemps over the town’s Liberty Pole.

The Liberty Pole was, simply, a wooden flagpole that had a weathervane displaying the word “LIBERTY” atop it, rather than a flag. It had no great aesthetic, monetary, or even practical value, but symbolically it became a universal talisman. The populace loved it, and the army deeply detested it.

New York’s relation to the military was very different from Boston’s. New York was always the obvious strategic military focal point of North America, both in the colonial wars and during the Revolution. The town’s citizens had more or less supported the French and Indian War (1754–60), and had tolerated the forces with relative ease as they passed through on their way to the front. After the Stamp Act riots of November 1765, however, forces permanently stationed in the city increased, and people wondered why, if they were supposedly on the continent to defend the frontiers, they were stationed in the city, hundreds of miles to the south.

While Bostonians were shocked when thousands of troops suddenly descended on them in October 1768, New Yorkers’ irritation grew more slowly but surely. The soldiers soon found themselves equally as annoyed with the “ungrateful” citizens. Neither community could take their anger out on those who truly merited it—the politicians in London—so both became increasingly obsessed with the other.

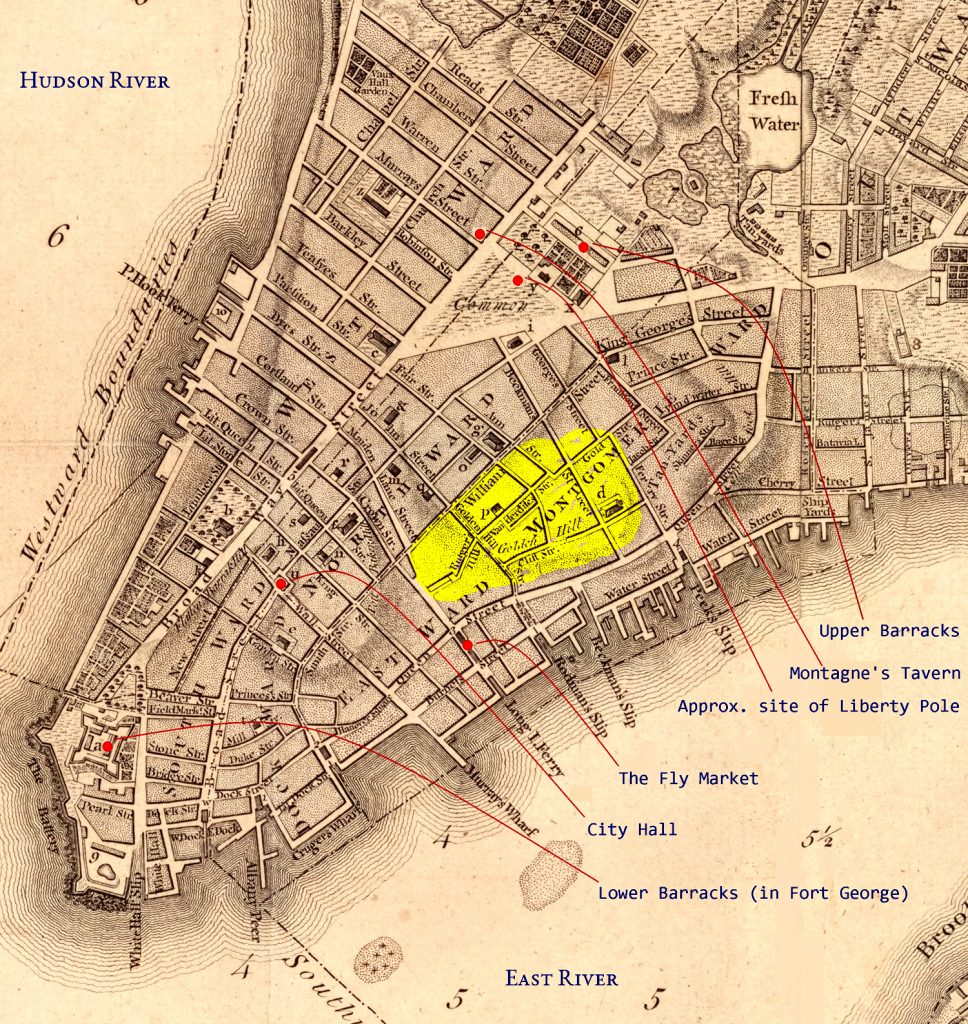

The first New York Liberty Pole—perhaps an analogue to Boston’s “Liberty Tree”—was erected in “The Fields,” the town common, today’s City Hall Park, in plain sight of the soldiers’ Upper (or north) Barracks. Hoisted on June 4, 1766, it was intended as a celebration of both the Stamp Act’s repeal and the king’s birthday. (The doomed equestrian statue of George III was commissioned for Bowling Green at the same time.)[3]

Soldiers cut the Pole down on August 10. A prank? Unlikely. The “Liberty Boys” put up another Pole in its place the following day, and a week of tense squabbling between townsmen and soldiery followed.[4] That Pole lasted only until September 23. A third Pole was erected two days after that. It lasted until March 1767, when the people celebrated the first anniversary of the Stamp Act’s repeal. The heavily-reinforced fourth Pole was promptly set up, and survived twenty-eight months, the army brass evidently having decided to prevent unnecessary controversy while they were pleading for firewood, grog, and other necessities from the local government.

Meanwhile, the imperial truce that Americans had hoped would be permanent began to fall apart. The Townshend Act was passed in June 1767, followed by a suspension of the New York Assembly for refusal to comply with the Quartering Act.[5] The following summer, New York’s merchants voted not to import British goods until the Townshend taxes were repealed—especially because the taxes had to be remitted in hard coin, which was virtually non-existent.[6]

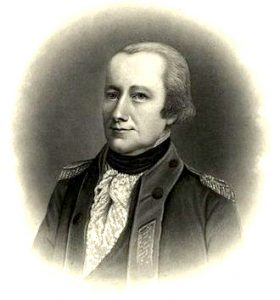

On September 11, 1769, the royal governor, Sir Henry Moore, who had managed to keep the two sides at bay, unexpectedly expired. That brought the acting lieutenant governor, Cadwallader Colden, who had become the most universally loathed character in the province in 1765, back to the top office once again, at the age of eighty-two.[7] Colden concocted a deal with the powerful De Lancey faction in the provincial Assembly: if the Assembly would disregard its commitment to ignore the quartering requests, Colden would endorse the merchants’ eagerly-desired creation of an emission of paper currency, which would require the governor to finesse the imperial prohibition against just exactly that.[8]

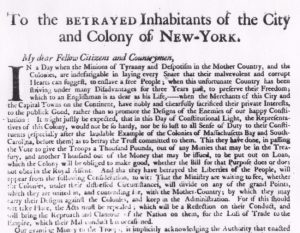

This bargain being accomplished, on December 16, 1769, Alexander McDougall anonymously published a fiery pamphlet, To the Betrayed Inhabitants of the City and Colony of New York, excoriating the “corrupt hearts” of the “minions of despotism,” and boldly naming Colden, the De Lanceys, and the Assembly as traitors to New York and the other American colonies that had jointly agreed to refuse compliance.

Matters went straight downhill. The politicians accused the pamphlet writer of libel, and queried every printer in town, trying to smoke him out. (The pamphlets had been deliberately printed in New Jersey.) On January 9, 1770, petitions of the Liberty Boys in favor of secret balloting and of limited length assemblies, were defeated by the fractious legislature in close votes.[9]

As far as the army was concerned, however, the Assembly was still dragging its feet regarding the promised provisions. One justification presented in defense of provisioning had been that the funds would first repay outstanding local debts for earlier provisions. But the army insisted that repayment should only come after satisfaction of its immediate needs.

The Crisis

On Saturday, the 13th of January, some forty soldiers attempted to topple the fourth Liberty Pole by drilling into it and stuffing the cavity with gunpowder. Some citizens, seeing this, ran to Montagne’s Tavern, the nearby hangout of the Sons of Liberty, and an aroused mob presently arrested the destruction. However, the furious soldiers attacked Montagne’s instead. They “entered it with drawn swords and bayonets, insulted the company and beat the waiter, . . . broke 84 panes of glass, two lamps and two bowls.”[10]

Another attempt on the Pole was tried on Monday the 15th, again prevented by vigilant townsmen. Meanwhile, the “Friends of Liberty” had issued “an Hand Bill . . . desiring the inhabitants to meet at Liberty Pole, on Wednesday, the 17th Instant, at 12 o’clock,” to “take their sentiments” on the recent outrages and the continuing controversies.[11]

In the evening of Tuesday the 16th, a third foray against the Pole was driven off. The citizens stood watches until ten p.m., past the soldiers’ normal retirement hour. However, in the small hours of the night, the soldiers returned and finally successfully downed the Liberty Pole. For added insult, they chopped it up and deposited the remnants by the porch of Montagne’s Tavern.[12]

Some three thousand citizens—out of a town of around 20,000—were estimated to have gathered that Noon at the site of the demolished Liberty Pole. You can guess their frame of mind from the heated language of the newspaper report. The designated speaker, introducing two resolutions against the military, asserted that the colony and the city had been providing “humane and benevolent treatment” for the troops, “although we have great ground to suspect that they are not stationed here to protect us.” Nonetheless, they have been so “ungrateful and insulting” as to cut down the Liberty Pole, “erected as a Memorial to Freedom. This base conduct is incontestable proof that they are . . . enemies to the peace and good order of this City. . . . And as the same diabolical spirit will naturally dispose them to use their utmost endeavors to enslave us, they must be considered . . . as enemies, mortal enemies, to all that is dear and valuable to Englishmen.”[13]

Two public resolutions were apparently adopted by acclamation:

- “That we will not employ any soldier, on any terms whatsoever, but that we will treat them with that abhorrence and contempt which the enemies of our happy Constitution deserve.”

- “That if any soldier shall be found in the night having arms . . . [they] shall be treated as enemies to the peace of this City.”

The scene was ripe for immediate confrontation. There was an “old house” belonging to the City, located between the site and the barracks, which was being used as a subsidiary barracks. The crowd voted to ask the City to remove it. “Thereupon, a Number of the Soldiers drew their Cutlasses and Bayonets, and desired the Inhabitants to come and pull it down. This new act of Insolence would have been productive of a very terrible affray, if the Magistrates and Officers had not interposed.”[14]

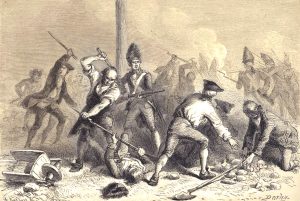

The street riot that came to be known as the “Battle of Golden Hill,” occurred two days later, on Friday the 19th. Historians draw heavily from a letter “To the Printer,” dated January 31, 1770, and published on February 5. Signed by “An Impartial Citizen,” its roughly 3,500 words do contain at least one nod to genuine impartiality.[15]

The confrontation began when two prominent Sons of Liberty, Isaac Sears and Walter Quackenbos, accosted half-a-dozen soldiers posting broadsides around the Fly Market, an open-air market located at the corner of Maiden Lane and Front Street. The broadside began with a bit of doggerel:

God and a Soldier all Men doth adore,

In Time of War, and not before.

When the War is over, and all Things righted,

God is forgotten, and the Soldier slighted.

The item continued with denigration of the “pretended Sons of Liberty” and their Liberty Pole, and complained of the citizens’ slights against the soldiers, who were never counted as “insolent or ungrateful, except in this city.” There was also a particularly pointed objection to the fact that the soldiers’ “wives and children” had ever been referred to as their “whores and bastards.”[16]

Isaac Sears “collared” the soldier posting the broadside, asserting he was putting up “libels against the inhabitants,” and stating that he would take him to the Mayor. Quackenbos grabbed the soldier carrying additional copies. A third soldier “drew his bayonet.” Sears then threw “a ram’s horn” at him and hit him in the head. All the soldiers but the first two accosted then “made off and alarmed others in the barracks.”[17]

While Mayor Hicks—who eventually became a Loyalist—was consulting colleagues and dithering over his alternatives, “a considerable number of people collected” outside. “Shortly after, about twenty soldiers, with cutlasses and bayonets, from the Lower Barracks, made their appearance.” At first, the soldiers were allowed through the crowd, but “Captain Richardson”—an individual obviously familiar to the readers, possibly a militia officer—“and some of the citizens, judging they intended to take the two soldiers from the mayor’s by force, went to his door to prevent it,” and “desired them to put up their arms.” Seeing drawn weapons, “many of the inhabitants, conceiving themselves in danger, ran to some sleighs that were near, and pulled out some of the rungs.”[18]

The mayor and Alderman Desbrosses ordered the soldiers back to their barracks, and the intruding soldiers removed themselves to the Fly Market. However, “the people were apprehensive that as the soldiers had drawn their swords at the mayor’s house . . . and declared war against the inhabitants, it was not safe to let them go through the streets alone.”[19] They followed to “the corner of Golden Hill,” then again as they proceeded up to the summit. Presumably, this means Gold Street, today barely an alleyway, with a very gentle rise for about 400 yards up to Beekman Street.

The writer asserts the citizens attempted to reason with the soldiers during this retreat. Here again, the historian has to raise a skeptical eyebrow. During the Stamp Act riots, plenty of unruly citizens were reliably reported taunting the soldiers, daring them to go ahead and fire, if they weren’t cowards. But the Stamp Act scene had been a carefully orchestrated protest that got out of hand only after several hours; the event on Golden Hill was an unplanned, spontaneous, angry flare-up.

At the summit, “a considerable number of soldiers joined” their fellows, and the writer asserts that one who appeared to be an officer explicitly ordered “Soldiers, draw your bayonets, and cut your way through them!”[20]

The writer contends that only half a dozen of the citizens were armed with so much as sticks or clubs, but they strove to hold their ground to prevent injury to defenseless others. One citizen lost his stick, and some soldiers chased him to “the main street”—presumably Broadway. While lunging at the quarry, a soldier struck a Quaker man standing in his doorway, cutting his right cheek. They then “madly” attacked a tea-water cartman and a fisherman, drawing more blood.

Back at the intersection, a sailor was injured in the head and the finger, while another was stabbed with a bayonet “so badly that his life was thought in danger.” A boy was chased “into Mr. Ellsworth’s house,” but was injured on the head by a cutlass; another soldier made a lunge with a bayonet at the woman who had answered the door.[21]

“Captain Richardson was violently attacked by two of the soldiers, with swords, and expected to be cut to pieces,” but he managed to defend himself with a stick. Two further instances of defenseless citizens being chased by armed soldiers are recounted, both without injury.

Yet another party of soldiers then appeared back at the Fly Market, and was confronted by more unarmed citizens. With a bayonet, at least one was chased to the mayor’s house, where he was spared only because the soldier tripped. Finally, some city magistrates got army officers to order the soldiers to stand down and return to barracks. “Several . . . were much bruised, and one of them badly cut.”[22]

Thus ended the “grand affray,”[23]but not hostilities. That evening, two lamplighters were attacked by soldiers. On Saturday morning, a woman was attacked with a bayonet, which miraculously only damaged her clothing. On Saturday at Noon, some sailors confronted some soldiers, and another riot began that was nearly as disastrous as the first. At one point, the mayor directly ordered the soldiers to their barracks, but was openly defied; they were only forced back by the appearance of an overwhelming number of citizens. Nonetheless, several bloodings were reported.

Consequences

The New York City Stamp Act riots had caused very little injury despite considerable property damage, but New Yorkers could hardly forget that many of the cannons facing out to sea on the Battery had been moved to the ramparts of Fort George, and aimed directly down at them in Bowling Green. Four years later, Golden Hill showed that imperial forces were entirely prepared to draw colonial blood in earnest.

So tempers cooled very slowly. On February 6, a new Liberty Pole, the fifth, heavily reinforced with iron sheaths, was paraded up from an East River wharf by a team of bunting-clad horses, to be erected on private property owned by one of the radicals.[24] (An attempt against it on March 24 failed, and it endured until the full British occupation began in September 1776.)

Meanwhile, six weeks after Golden Hill, the five fatalities of the Boston Massacre (March 5, 1770) took the continental spotlight away from New York. Early in May, many of the soldiers were debarked away to Pensacola, and around that time word also arrived that Parliament had rescinded all the Townshend taxes save the important tax on tea.[26] Intermittent protests and minor riots continued, as radicals remained adamant that nonimportation should be maintained until all the taxes were cleared, but by this time, over six months since nonimportation had begun in New York, not only the merchants, but the locality’s middle and lower classes were really hurting.

The De Lancey faction engineered a public poll on July 9, 1770, that indicated exhaustion of all will to boycott anything other than the East India Company’s hated tea.[27] New York’s nonimportation agreement was, notoriously to some, the first to collapse, and the surrender of the other port cities swiftly followed, ushering in the second and final interlude of relative imperial peace.

[1]Joseph S. Tiedemann, Reluctant Revolutionaries: New York City and the Road to Independence, 1763–1776 (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1997), 118.

[3]Edwin G. Burrows & Mike Wallace, Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 (Oxford University Press, 1999), 203; Paul A. Gilje, The Road to Mobocracy: Popular Disorder in New York City, 1763–1834 (Chapel Hill and London: University of North Carolina Press, 1987), 53.

[4]Tiedemann, Reluctant Revolutionaries, 110.

[5]Richard Archer, As If an Enemy’s Country: The British Occupation of Boston and the Origins of Revolution (Oxford University Press, 2010), 68.

[6]Tiedemann, Reluctant Revolutionaries, 129.

[7]Burrows & Wallace, Gotham, 210.

[8]Tiedemann, Reluctant Revolutionaries, 141.

[9]Tiedemann, Reluctant Revolutionaries, 146; Patricia U. Bonomi, A Factious People: Politics and Society in Colonial New York (New York and London: Columbia University Press, 1971), 275.

[10]New-York Gazette and Weekly Post-Boy, February 5, 1770, 2. Facsimile copy in New-York Historical Society Library.

[13]New-York Gazette and Weekly Post-Boy, January 22, 1770, 3.

[14]New-York Gazette and Weekly Post-Boy, February 5, 1770, 2.

[24]Tiedemann, Reluctant Revolutionaries, 150; Burrows & Wallace, Gotham, 211.

7 Comments

Informative and enjoyable! I especially liked the maps and present day pictures of “where it happened.” And a great guide for my next visit!

Erratum: Due to my original, erroneous conflation of the “Golden Hill” hillside with Golden Hill Street (now simply the eastern blocks of John Street), the location of the most sanguinary confrontation is misstated. It was most probably at the current intersection of John Street and William Street (as correctly pictured), rather than at Gold and Beekman Streets.

This piece is really well written—and highlights the era of the “liberty poles”—well enough to keep my attention throughout! Nice job.

An erudite and fascinating description of the Liberty Poles story, vivid even in London (England), where the US is still occasionally referred to, whimsically, as “the Colonies”.

My ancestors, the Vandercliffs, owned Golden Hill in the 1600s, and laid out Gold Street. For that reason, I have researched this topic. Your map is wonderful. I created one and was determined to find where the Mayor’s house was. It was at “Queen and Wall opposite Peter Remsen’s.” I did not know where I found this, but I believe it was in an old guide book to NYC.

Thanks, Jon. The contention over the Liberty Pole reminds me of the cutting of the elm at Gisors that I learned about from “Holy Blood, Holy Grail”. It also made me wonder whether Colden Avenue in the Bronx was named after THAT Colden; I guess the answer’s in McNamara’s “History in Asphalt”. I think the building in the Google Street View is the one Fred Cookinham took us into the lobby of on a walking tour, where the indoor walkways preserved the layout from that time.

Thanks to all commenters, and special thanks to Ms. Becker for the location of the Mayor’s house. It makes sense, as Queen (Pearl) and Wall Street is less than half the distance from the site of the Fly Market to (then) City Hall. The house would have been in sight as soon as anyone turned the corner of Queen Street, and would have been the logical nearest spot for a pursued citizen to flee for safety.